Brotherhood Is Powerful

by Pauline Kael

John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King, based on the Rudyard Kipling short story, is an exhilaratingly farfetched adventure fantasy about two roughneck con men, Danny and Peachy (Sean Connery and Michael Caine), in Victoria’s India, who decide to conquer a barbarous land for themselves, and set out for Kafiristan, a region which was once ruled by Alexander the Great, to make themselves kings. With twenty rifles, their British Army training, unprincipled rashness, cunning, and a few wild strokes of luck, they succeed, for a time. As a movie, this Empire gothic has elements of Gunga Din and of a cynical Lost Horizon, along with something that hasn’t been a heroic attribute in other Empire-gothic movies: the desire to become the highest-ranking person that one can envision. The heroes are able to achieve their goal only because of the primitiveness of the people they conquer, and this is very likely the stumbling block that kept the movie from being financed for the twenty-odd years that Huston wanted to do it. Maybe he was able to, finally, on the assumption that enough time has passed for the heroes’ attitude toward the native populations of India and Kafiristan—the benighted heathen—to seem quaint rather than racist. Huston’s narrative is both an ironic parable about the motives and methods of imperialism and a series of gags about civilization and barbarism. When savages in war masks are hit by bullets, the image is a sick-joke history of colonialism, and when the vulgarian heroes try to civilize the tribes they conquer, they obviously have not much more than their own military conditioning to draw upon. Danny and Peachy are British primitives who seek to turn the savages into Englishmen by drilling them in discipline and respect for authority. Danny becomes as sanctimonious about that mission as Victoria herself, and is baffled when the natives show ingratitude.

The script, by Huston and Gladys Hill, is a fine piece of craftsmanship, with every detail in place, and with some of Kipling’s devices carried further, so that the whole mad, jinxed adventure is tied together. But The Man Who Would Be King isn’t rousing, and it isn’t a comedy, either. It’s a genre movie made with full awareness of the campy pit into which it will sink if the laconic distancing ever lapses. Huston has to hold down the very emotions that most spectacles aim for; if he treated the material stirringly, it would take the audience back to the era when we were supposed to feel pride in the imperial British gallantry, as we did at some level, despite our more knowledgeable, disgusted selves, at movies like the 1935 Lives of a Bengal Lancer. This film doesn’t dare give us the emphatic identification with what’s going on inside the heroes which we had with Gary Cooper and Franchot Tone in Bengal Lancer. And Huston, who has never been interested in spectacle for its own luxurious sake, doesn’t make a big event of the adventure, the way Capra did with the arrival at Shangri-la—when he practically unveiled the city. Shot in Morocco, with Oswald Morris as cinematographer and Alexander Trauner as production designer, The Man Who Would Be King is in subdued reds and browns, and the persistent dusty earth tones underscore the transiency of the heroes’ victory. There are no soaring emotions. Huston tells his whopper in a matter-of-fact tone, and he doesn’t play up the cast of thousands or the possibilities of portentous spectacle in the bizarre stone “sacred city” of Alexander the Great, built on a mountain.

The director’s love of the material is palpable; it makes one smile. Yet the most audacious parts of the film don’t reach for that special clarity which makes action memorably poetic. There are lovely, foolish poetic bits—a panoramic view of warring armies pausing to genuflect when holy men walk through the battlefield, and the brave last flourish of Billy Fish (Saeed Jaffrey), the interpreter for the heroes, who dies charging their enemies, pointlessly, in the name of British military ideals—but these episodes are offhand and brief. Huston’s is a perverse form of noblesse oblige—he doesn’t want to push anything. He won’t punch up the moments that are right there waiting, even though we might have enjoyed basking in them, and getting a lift from them. He sets up the most elaborate, berserk fairy-tale scenes and then just sits back; he seems to be watching the events happen instead of shaping them. Huston has said that Danny and Peachy are destroyed because of folie de grandeur, and that’s what he risks, too. I admire his pride; he treats the audience with a sophisticated respect that’s rare in genre films, and this movie is the best sustained work he’s done in years. Even Edith Head’s costume designs and Maurice Jarre’s musical score rise to the occasion, and the animal noises (they sound like cows lowing through giant megaphones) that accompany the primitive rites are terrifyingly creepy. But Huston’s courtliness has its weakness. No doubt he believes in telling the story as simply as possible, but what that means in practice is that he shoots the script. It’s exemplary, and he’s a good storyteller. But he’s not such a great movie storyteller here. I don’t think Huston any longer plans scenes for the startling sprung rhythms of his early work. The camera now seems to be passively recording—intelligently, beautifully, but without the sudden, detonating effects of participation. Huston has become more of an illustrator. And so the ironies in The Man Who Would Be King go by fast—when we want them to vibrate a little.

Huston’s even-tempered narrative approach doesn’t quite release all that we suspect he feels about the material. It may be that he’s so far into the kind of thinking that this story represents that he doesn’t take us in far enough. If he had regressed to an earlier stage of movie history and presented Kipling’s jingoism with emotional force, the film might have been a controversial, inflammatory epic. If he had rekindled the magical appeal of that jingoism and made us understand our tragic vulnerability to it, it might have been a true modern epic. The way he’s done it, the story works only on the level of a yarn. But it’s a wonderful yarn. Huston shares with Kipling a revelling in the unexpected twists of behavior of other cultures, and he doesn’t convert the story into something humanistic. The ignorant natives are cruel and barbaric; if they’re given a chance, they don’t choose fair play. And Huston leaves it at that—he doesn’t pussyfoot around, trying to make them lovable. Huston has a fondness for the idiosyncrasies of the natives, and he doesn’t hate the heroes who go out to exploit them. Huston is cynical without a shade of contempt—that’s why the film is likable. Yet when you play fascinated anthropologist, equally amused by the British and the natives, you may have licked the problem of how to do Kipling now without an outcry, but you’re being false to why you wanted to film the story in the first place. Despite the film’s ironic view of them, Danny and Peachy, who can sing in the face of death, represent courage and gallantry. Huston may spoof this when he has Peachy bawl out Danny for rushing in to attack an enemy army, and Danny, who has won the battle single-handed, apologize that his “blood was up,” but the love of this crazed courage is built into the genre, and even if you leave out the surging emotion of the arrival of the British relief column, it’s the Britishers here—and their devoted Billy Fishes—who represent civilization. Their ways of killing are cleaner—they don’t kill for pleasure. Huston’s irony can’t remove all this—it merely keeps it from being offensive.

The theme of The Man Who Would Be King gets at the essence of the attitudes underlying John Huston’s work. Huston might be the man without illusions on a quest. Here, as in The Maltese Falcon, The Asphalt Jungle, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, his characters are after money. But when Danny and Peachy are battling mountain snowstorms, risking blindness and death to get to the backward country they mean to pillage, one knows that it isn’t just for gold—it’s because conquering and looting a country are the highest score they can imagine. And when they view Alexander the Great’s treasure, the jewels and gold pieces seem a little ridiculous; the treasure will be scattered, like the gold dust in The Treasure of Sierra Madre. What matters in Huston films is the existential quest: man testing himself. It’s a great pity that Huston didn’t get to film Mailer’s An American Dream, which is also about a man who would be king. (All Mailer’s writing is.) Mailer’s book, being in contemporary terms, might have challenged Huston right to the bone. The Kipling story, with its links to old adventure-genre movies, and its links to the childhood tastes we have disowned, doesn’t quite.

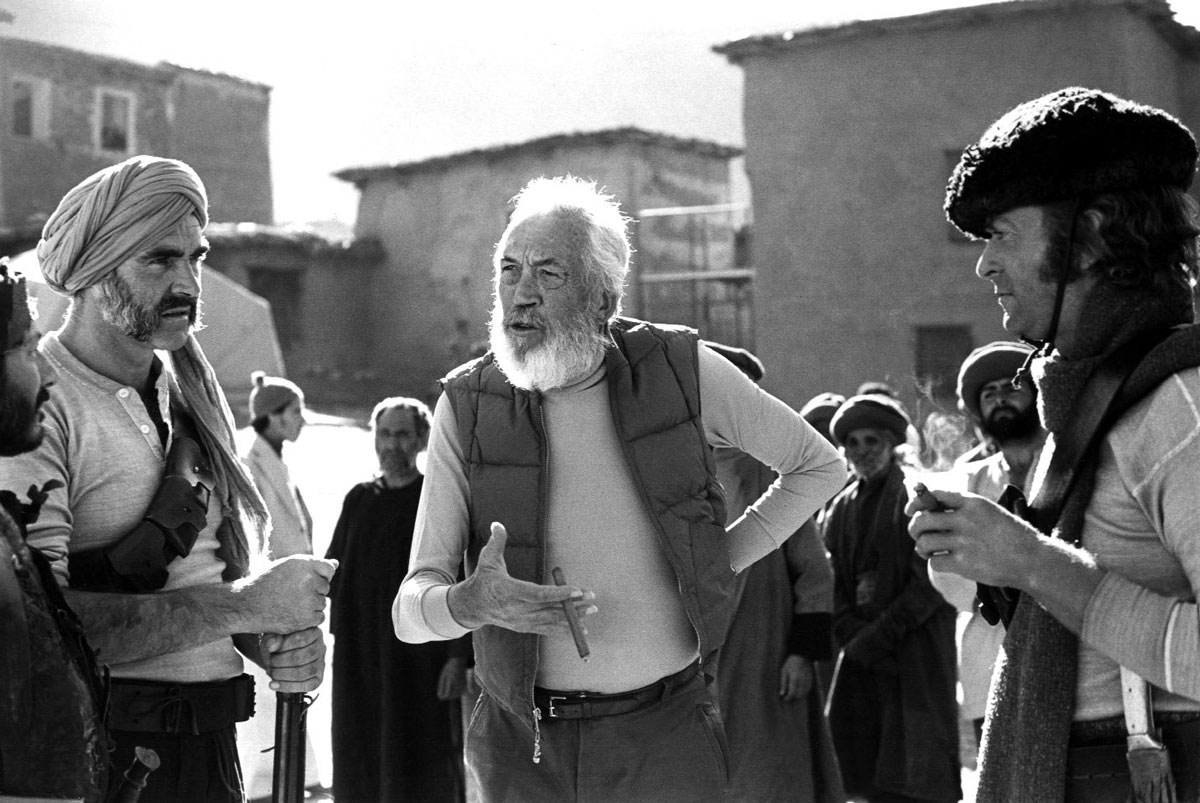

Huston finds a grisly humor in the self-deceptions of ruthless people chasing rainbows; that might almost be his comic notion of man’s life on earth. He earns esteem by not sentimentalizing that quest. (Yet his inability to show affection for characters who live on different terms shows how much the rogues mean to him.) Huston isn’t too comfortable about any direct show of emotion; he’s in his element (and peerlessly) with men who are boyishly brusque, putting down their own tender feelings shamefacedly. When he first prepared this script, Gable was to be in the Connery role and Bogart in the Caine role. Connery is, I think, a far better Danny than Gable would ever have been. Gable never had this warmth, and never gave himself over to a role the way Connery does. With the glorious exceptions of Brando and Olivier, there’s no screen actor I’d rather watch than Sean Connery. His vitality may make him the most richly masculine of all English-speaking actors; that thick, rumbling Scotsman’s voice of his actually transforms English—muffles the clipped edges and humanizes the language. Connery’s Danny has a beatific, innocent joy in his crazy goal even when he’s half frozen en route; few actors are as unself-consciously silly as Connery is willing to be—as he enjoys being. Danny’s fatuity is sumptuous as he throws himself into his first, half-embarrassed lofty gestures. Connery plays this role without his usual hairpieces, and, undisguised—bare-domed—he seems larger, more free; if baldness ever needed redeeming, he’s done it for all time. Caine has the Bogart role, which means he’s Huston’s protagonist; Peachy is the smarter of the two, the wise-guy realist, loyal to Danny even when he’s depressed by Danny’s childishness. We see through Peachy’s sane, saddened eyes the danger in Danny’s believing himself a man of destiny, and Caine manages this with the modesty of a first-rate actor. He stays in character so convincingly that he’s able to bring off the difficult last scene, rounding out the story conception, when it becomes apparent that Peachy has “gone native.”

The central human relationship is between these two uneducated working-class blokes, who at first share a fantasy, and who remain friends—brothers, really, since they’re Masons—even when their fantasies diverge. The entire plot hinges on Freemasonry—not however, used philosophically, as it was in The Magic Flute, though Kipling himself was deeply involved in the brotherhood, and Christopher Plummer, who plays him here, wears a Masonic watch fob. Plummer, hidden by a thick brush mustache, gives a blessedly restrained performance as the straitlaced young editor in India. In terms of historical accuracy, however, he’s not young enough for the part. Brother Kipling—an “infant monster,” Henry James called him—was only twenty-two when he published the story. In the movie, it seems appropriate that the watch fob should set the whole adventure in motion; the brotherhood that links the two rowdy crooks, the nearsighted journalist, and the shaven-headed monks in the temple of Kafiristan is like a schoolboys’ secret society that has swept the world. In the story, Kipling was able to satirize his own gnomic vision of fraternity, and at times Huston and Gladys Hill, ringing changes on the mystic-fraternity theme—“rejuvenating” it—might almost be borrowing from Edgar Rice Burroughs. Huston seems to be enjoying himself in this film in the way he hasn’t for a long time. It communicates the feeling of a consummated dream.

One of the incidental benefits of movies based on classics is that filmgoers are often eager to read the book; Allied Artists, which produced this film, and Bantam Books have just struck a low note by putting out a gold-covered paperback novelization of Kipling’s story. This makeshift Kipling, written by Michael Hardwick, combines the story and the screenplay, unnecessary descriptions, and bits from Kipling’s life to fill a hundred and thirty-seven pages. The whole new practice of film novelizations is a disgrace. It sickens the screenwriters who have written original screenplays to see their dialogue debased into a prose stew, but at least they are alive and in a position to fight against it. If they’re suckered, it’s partly their own damned greedy fault. But here is a movie inspired by love of Kipling—apparently, Huston first read the story when he was twelve or thirteen, and it meant enough to him to nag at him many years later—and this love has had the effect of temporarily displacing the story and putting drivel in its stead.

Hunger cannot be the excuse: Allied Artists and Bantam Books are not poor and desperate, and the profit to be made from this venture is not likely to be vast. What is the rationale for this garbagizing of literature? I don’t think “The Man Who Would Be King” is a great story, but it’s a good one—good enough to have turned people into Kipling readers, maybe, if it had been made readily available in an edition with one or two other Kipling stories, and with the movie-photo tie-ins that will attract readers to this gold beauty. Since Kipling’s work isn’t in screenplay form but in a highly readable form, the motive for this mass-marketed paperback seems almost like giggly mischief—a folie of debasement. That could be another term for business as usual. Allied Artists and Bantam Books, why are you doing this?

The New Yorker, January 5, 1976

1 thought on “THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING – REVIEW BY PAULINE KAEL”

How about here reviews of A Passage To India & Empire Of The Sun?