Three College Kids From Michigan Are The Latest To Stake Their Claim In The No-Mans-Land Of Low-Budget Horror Films

by Dan Scapperotti and Robert Alan Glover

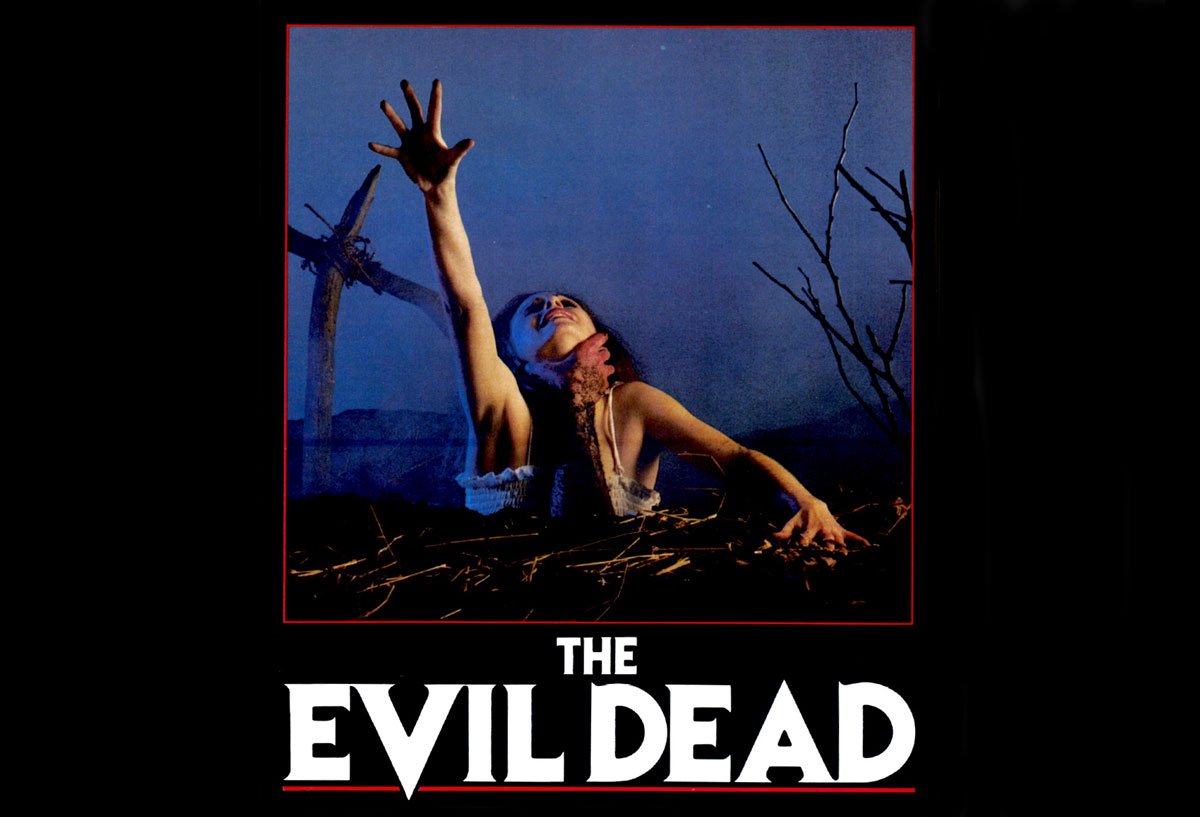

At first glance, The Evil Dead appears to be another shlocky, grade-Z shocker—one so bloodsoaked that it probably could even make Tom Savini vomit. Made by a group of very young, semi-professional filmmakers who started their own Detroit-based production company (Renaissance Pictures), The Evil Dead (originally titled Book of the Dead) was filmed in the rustic backwoods of Tennessee for the paltry sum of $330,000. It hardly sounds like the makings of a horror classic.

But this film, which began production nearly four years ago, has quite surprisingly become the horror movie to see; it’s grabbed the shocker spotlight the way John Carpenter’s Halloween and George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead did in past years. Not bad for a movie that look more than two years to find a distributor.

How did The Evil Dead make the big time? In 1982, the film’s writer/director Sam Raimi and producer Rob Tapert interested veteran film promoter Irvin Shapiro in their picture. (Raimi first saw Shapiro’s name in a copy of Variety.) Shapiro is known for his expert handling of independent films, and agreed to represent them. Shapiro then trotted off The Evil Dead to the Cannes Film Festival, the most prominent and splashy of international marketing scenes. Shapiro was also handling overseas distribution rights for George Romero’s film, Creepshow, and had brought Stephen King to Europe to pump up publicity for the him. King caught an early screening of The Evil Dead, and to say the least, he was really thrilled with it.

“The most ferociously original horror film of 1982,” declared Stephen King in a lengthy movie review in Twilight Zone magazine. “The Evil Dead has the simple, stupid power of a good campfire story—but its simplicity is not a side-effect. It is something carefully crafted by Raimi, who is anything but stupid.

“(In the film), the camera has the kind of nightmarish fluidity that we associate with the early John Carpenter,” King continued. “(The camera) dips and slides and then zooms in so fast you want to plaster your hands over your eyes. The film begins and ends with crazily exhilarating shots that make you want to leap up, cheering. (At Cannes, French cinema-freaks did exactly that.) In the first, we are slumming giddily over a swamp; in the last, we come plunging madly down a wooded hill into that damned deserted cabin where all the madness, dismemberment, and lunacy occurred.”

A positive word from Stephen King on anything dealing with the horror genre is like money in the bank, and suddenly The Evil Dead was a comer. Several foreign markets, including the Hong Kong area, snatched up the Renaissance Pictures production, and domestically New York’s New Line Cinema picked up distribution rights and began releasing the film in New York and Detroit in early spring, with further release dates to follow. Last February, The Evil Dead opened in 20 situations in the U.K., where the film was second only to E.T. in terms of grosses for the first half of February.

Other critics applauded the film with the same intensity as King: The Los Angeles Times called it “an instant classic.” However, before these wonderful words of praise, Cannes’ glamor and glitter and Britain’s burly box office figures, there was originally just a handful of inexperienced Michigan suburbanites trying to throw a film together.

Here’s a quick rundown of who they are: Sam Raimi, who was only 20 when he wrote and directed The Evil Dead; his producer, Rob Tapert, was 26. The gruesome special effects were achieved by Tom Sullivan, 24, and Bart Pierce, 30. And the entire cast, including Bruce Campbell, who doubles as executive producer, were college kids.

Raimi met Tapert and Campbell while attending Michigan State University, and together they formed their own small film society. Soon after, the trio look on a bigger challenge, and their production company was officially incorporated in 1979. Their first Renaissance Pictures film, The Evil Dead, developed from a 30-minute, Super-8 short, Within the Woods, which was a surprise success with enthusiastic local audiences in Grosse Point, Michigan—grossing several thousand dollars. Having established that they had a potential “winner” on their hands, they set about raising capital for the full-length version.

“It involved working at odd-jobs, a lot of midnight meetings and knocking on the doors of various investors,” said Raimi. “To save money, we had to live at home with our parents.” Raimi, Tapert and Campbell put up what money they had, and then went to look for the rest. Tapert and Campbell dropped out of Michigan State and raised much of the film’s small budget from private investors: lawyers, doctors, builders and contractors, among others.

With the money finally in their hands, the group began filming in September, 1979, far from the Detroit area. “For one thing,” Tapert complained, “the Michigan Film Commission was in an embryonic state of existence. They’re not used to working with large-scale, feature film productions, or suggesting the ideal shooting location.” Consequently, by the time Tapert’s crew was sent to commence filming, the Michigan locations they needed were on the verge of winter weather.

“The crew struck out for Morristown, Tennessee—some 200 miles from Knoxville—for their principal location. More than two months were spent in Tennessee, and shooting sites included a century-old cabin and atmospheric woodlands.

Shooting resumed in May, 1980 back in Marshall, Michigan for “cover shots” and inserts, including scenes involving decapitation, decomposition, dissection, eye-gouging and other gruesome effects under the supervision of Tom Sullivan, who was involved in another Michigan-based genre film, Cry of Cthulhu [8:4:29], which never passed the pre-production stage.

The Evil Dead’s plot concerns a mysterious book—unearthed by five college students while visiting a remote mountain cabin—that has the power to summon forth evil forces. This evil possesses the students one by one, and they turn into hideous versions of their former selves. Sullivan was under a great deal of pressure from the producers to create several different monsters, since Raimi felt that if all the possessed creatures looked the same, the film would quickly lose impact.

“We wanted to change their appearance and play on the characters no matter how thinly drawn they were early in the film and warp them out to become horrific,” said the director. One character, played by Ellen Sandweiss, an old high school friend of Raimi’s, was a vivacious and attractive young woman before being possessed by the evil force. Her appearance was transformed into an inhuman living doll—always laughing and smiling, but in a hideous, horrible sense.

Many of the special effects sequences were shot in and around the Detroit area: a garage and basement in northwest Detroit, a backyard in the suburbs and in nearby Franklin, Michigan. Working in such primitive conditions made ingenuity a keynote of The Evil Dead.

An example of Raimi’s makeshift, corner-cutting methods occurred in the film’s most bizarre and effective scene—a woman is literally raped by nature. Vines and branches wrap themselves around the hapless woman and spread-eagle her on the ground as other foliage whips the clothes from her body. The effects were done using the clever, but inexpensive method of reverse motion, The him was loaded into the camera backwards and the vines, which were very elastic by nature, were wrapped around the actress. Bunches of the vines were then simply pulled away. When the film was run correctly through the projector it would give the effect of the vines jumping to her.

Other effects include dummy heads created by Sullivan for shots of melting demons. Intestines, blood and bodily fluids, which came from freshly killed roosters, came shooting out with the speed of the most defective plumbing imaginable. The standard foam rubber and latex appliances were used, as well as contact lenses, which could be worn for only 15 minutes at a time. For a sequence in which the evil dead actually come to life, a miniature model was used covered in chicken skin. A mixture of coffee, Kayro syrup and food coloring was used to simulate the ever present blood.

For a shot of a creature aging 2.000 years in a matter of seconds, Sullivan and his assistant Bart Pierce used something they termed “double frame animation,” which helped eliminate the necessity for expensive post production work. To create the illusion of live action they would shoot a frame, move the model slightly and shoot the frame again giving it a false blur. Sometimes the frame was exposed three or four times.

“In one shot we might create a liquid feel in one quarter of the frame, in another part of the frame would be a stop motion effect happening at a certain speed, and in another part of the frame a stop motion effect happening at twice the other speed,” Raimi said. “So you’d have all these different shots taking place in the one frame,”

Besides coming up with a term for their plucky animation techniques, the filmmakers coined another phrase in detailing their tracking-shot methods. Since the crew couldn’t afford a Steadicam, they came up with their own version, a “Shaky-cam,” which was used in the film’s surprise ending. In the final minutes of The Evil Dead the entity, which has haunted the students, rushes toward the cabin. Approaching three doors at the back of the cabin, the demon blows them open and then exits out the front where the lone survivor (Campbell) turns to meet his fate.

A very light weight, silent 16mm camera was mounted on a piece of wood about 2.5 feet wide. Raimi grabbed both ends of the board and ran full tilt towards the building. As he approached each door he yelled, “one, two, three” and at each count someone inside the cabin opened a door, allowing him to rush through. A very wide angle lens was used to minimize all the bumps and jiggles inherent in the method.

The same equipment was used for the opening boat sequence. Raimi strapped the camera to his arm, holding it at water level. As he approached an obstacle he simply raised his arm. On film the tracking shot appears to glide over tree stomps and rocks with an incredibly smooth motion.

Even when things went well as in the tracking shots, Rob Tapert discovered that the lot of a film producer isn’t always easy. The screenplay called for a bridge, which two of the characters use to try to make an escape, but are stopped by a giant, invisible hand which crushes the bridge (and them). The Tennessee Film Commission gave Renaissance Pictures a condemned old bridge, and wreckers were hired to twist and bend the girders and bridge supports.

Because the approaches to the structure had been overgrown with weeds, the production crew had to lay about ten feet of gravel to simulate the road. Unfortunately, that ten feet was county property, and Tapert had to get permission from the local road commissioner to lay the gravel. The commissioner wouldn’t give his permission, unless Tapert came up with $500. Backed against the wall, Tapert handed over the cash.

“We were going to film this scene in three days,” recalled Tapert, “And that was our mistake because the guy died that night. The other commissioners then said we hadn’t paid, and we had to fork over another $500.

“We knew what we were getting into,” Tapert continued. “We were aware that this was our first time and that mistakes were possible. But we knew that we could learn from our mistakes. Consequently, I feel that a lot was learned along the way.”

The boys from Michigan have two other small-budgeted projetct, Relentless and The Happy Valley Kid waiting in the wings for Renaissance Pictures. However, if The Evil Dead finds an audience in a manner like Friday the 13th or Halloween, then The Evil Dead 1300 AD may be their next project.

SOURCE: Cinefantastique, Vol 13 No 6/Vol 14 No 1