by Jeffrey F. Keuss

During the 71st Academy Awards, Steven Spielberg eulogized the passing of director Stanley Kubrick with these words:

He died before he could witness the century he had already made famous with 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stanley wanted us to see his movies absolutely as he envisioned them. He never gave an inch on that. He dared us to have the courage of his convictions, and when we take that dare, we’re transported directly to his world, and we’re inside his vision. And in the whole history of movies, there has been nothing like that vision ever. It was a vision of hope and wonder, of grace and of mystery. It was a gift to us, and now it’s a legacy. We will be challenged and nourished by that for as long as we keep the courage to take his dare, and I hope that will be long after we’ve said our thanks and good-byes.1

Born 26 July 1928 in New York City, Stanley Kubrick remains one of the most talked about film directors of the past century. He went on to receive Best Director Academy Award nominations for Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon. Each of those films also earned Kubrick Best Screenplay nominations, as did Full Metal Jacket. In addition, Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon received Best Picture nominations. Kubrick’s only Oscar came for the special effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey. In 1997, he received the D. W. Griffith Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Directors Guild of America. That same year Kubrick began shooting Eyes Wide Shut, returning to film-making after a ten-year absence. He died in his sleep on 7 March 1999, soon after turning in his final cut of the film.

Part of the importance of Kubrick’s vision as a director was that he was someone who immersed himself in the world of words as well as vision. Kubrick began his adult career as a photographer before making the move to film but was always deeply interested in narrative. Only Kubrick’s first two feature films, Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, were based on original stories that he created (the former with Howard O. Sackler).

When he teamed up with producer James B. Harris in the early 1950s, they began looking for literary properties to adapt, since that was Harris’s speciality and at that time it was easier for young film-makers to get a film made based on an existing work.

Kubrick had always been a voracious reader and the success of his next few films convinced him that he was better at adapting stories that interested him than inventing his own material (although of course he made significant contributions to the finished screenplay on all of his films).

1. Viewing vs. Reading Film

To begin our discussion of Kubrick as a film-maker is to begin with a reminder that Kubrick’s films should be ‘read’ as opposed to ‘viewed’. I am differentiating between these terms ‘viewing’ and ‘reading’ as passive and active ways of approaching film. Too often, the notion of film as something we view rather than read results in a great loss of riches that film by directors such as Kubrick have to offer.

As a medium we merely ‘view’, film becomes something we ‘understand’ without struggling to improve our understanding. For example, the photographic image stands in contrast to a text, which, with a single word, can shift from representation to reflection. We look at a photo and recall its source — its very ‘stillness’ seems to allow and encourage us to make a reference — e.g. Who is this in the picture? When was it taken? Where was that building in the background? It is this that led cultural theorist Roland Barthes to call the photographic image pure contingency — that is, the photograph is always something that is representational and therefore contingent on something ‘other’ for meaning to arise. In contrast, more so than other arts, film offers an immediate and fully contextualized presence to the world — it is self-referential and makes its own reality. Ironically, it is precisely because, as James Monaco notes, films ‘so very clearly mimic reality that we apprehend them much more easily than we comprehend them’.2 Film semiologist Christian Metz comments that, as an easy art, cinema is in constant danger of falling victim to this easiness as he surmises: ‘A film is difficult to explain because it is easy to understand.’3 This power, inherent in the cinematic image, seduces: we lay ourselves open to the massive doses of meaning and information movies convey without questioning how they tell us what they do tell us. It is in reading film, seeing deeply with a critical turn — reading as opposed to merely viewing — that is essential to plumbing the rich depths of films. Film and the very nature of the cinematic image itself resists reading: its immediacy, its lack of distance, its illusion of pure reference does make this difficult. In short, movies need ‘unpacking’ and critical analysis no less than other ‘texts’.

2. Reading the Religious in Stanley Kubrick

One aspect of Kubrick not fully addressed however is that he was deeply concerned with the religious aspects of life as well.4 While not overtly playing his cards in any dogmatic pronouncements, reading the films of Kubrick shows a director who invokes an experience of the numinous and the predestined, what theologian Rudolf Otto would call the experience of the holy, the mysterium tremendum et fascinans.5 It is a mystical experience, an ecstasy at the end of things, that continually threatens to consume or immerse the subjects of his films and ultimately draws us as viewers into this experience of the holy as well.

Anthropologist of Religion Mary Douglas has written that a ‘person without religion would be the person content to do without explanations’.6 To read Kubrick’s films is to partake of films that display a profound discontent with the state of modern humanity akin to the fervour of an evangelist calling for an encounter with something more, something larger, and ultimately something transcendent.

One of the early sages of film critical theory is media theorist Marshall McLuhan. In The Medium is the Massage, McLuhan insisted that we cannot understand the technological experience from the outside as a ‘viewer’ from an objective space. We can only comprehend how the electronic age ‘works us over’ if we ‘recreate the experience’ in depth. He makes this point with regard to mass media:

All media work us over completely. They are so persuasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered. The medium is the massage. Any understanding of social and cultural change is impossible without knowledge of the way media work as environments.7

In short, to read film is to first accept the fact that it will take work and is not a passive enterprise — but that should not take the joy out of it. Merely ‘viewing’ any image is ultimately a form of both idolatry (passively becoming the object rather than the subject) and iconoclasm (seeing only the surface and not into the depth of a thing is ultimately to destroy it). This is the task of religion and the call of people of faith.8 Whether it is the empty cross or a filled chalice, Christian theology has ample reason to attend to images, both because we do not want to be in their thrall unawares and because their power already signals some sort of ‘religious’ resonance. We know the power of certain images to hold sway over the imagination. Media mediates through and with images — we are expected to know the meaning of the void created in the New York skyline after September nth and the toppling of Saddam’s image in central Baghdad, played over and over on television screens. We know at an innate level that something is going on when certain images hit us — their power to embody and make present the very being of their object. Profound responses in the presence of images (desire, fear) transcend the sorts of boundaries academics establish between the canon of so-called high art, folk and tribal arts, popular logos from Starbucks to Nike, and the devotional images found in our places of worship. Film is a medium of immediate imaging — where some images and texts require some reflection and repose prior to understanding, most film demands and gets an immediate reaction and understanding. It displays a world much more convincingly and immediately than any other symbolic form. As mechanical reproduction, it gives the illusion of pure reference. As moving picture, it seems to offer an ongoing experience of time present and therefore of presence.

Three Pointers for Film Reading

These are three ‘pointers’ that Barbara De Concini9 suggests as a way of beginning to school ourselves in ‘reading’ films. We shall apply these to a representative viewing of three of Kubrick’s films. As she suggests, since the viewer tends to identify with the camera’s lens as the authoritative angle of value to be considered (which is roughly equivalent to the point of view in a novel), we should school ourselves to pay attention to the camera — what it does, what and who it shows and doesn’t show. De Concini suggests the following:

1. How the camera frames and holds the subject. How much of the human figure is in view, how much of the surroundings? What happens to our perceptions when the character is presented to us in extreme long shot, a mere speck on the screen as opposed to in extreme close-up, and where the individual face can become a whole spiritual landscape? An image in painting or a photograph can be rich with symbolic import, but it must achieve its effects within the frame. A movie is a moving picture, a multiplicity of frames (astoundingly, as many as 180,000 in a two-hour film).

2. The camera’s angle of vision. The angle from which a subject is photographed has an impact on how the image ‘reads’. As Louis Giannetti demonstrates in Understanding Movies, an eye-level shot suggests parity between viewer and subject, while high angles reduce the subject’s significance, suggesting vulnerability, and low angles do the opposite, creating a sense of dominance over the viewer.

3. Camera shots tend to acquire meaning when they are seen in relation to other shots. Images that are created within the context of the film gain meaning through their associations with other images clustered within the film. In addition, as viewers we bring our lived experience to these images and they gain further meaning. This is one of the most characteristic ways in which the cinematic image expresses the ‘something more’. We can call it symbolic and we will not be incorrect. But, as people who are used to the written text, our expectations of the symbolic may mislead us. Here the process is often a quite humble one which falls into a sort of middle range of meaning between the immediacy of the iconic and the latency of the symbolic. Through editing, the film-maker elaborates visually on some natural links and fairly straightforward connections, piecing together sets of visual associations, patterning thematic and metaphorical affinities for us through the iterative process of the cinema.

In contrast to paintings and photographs, a film can build its effect gradually, even modestly and quietly, alternating stretches of restraint, when the image is less saturated with meaning, with the occasional epiphany. A surprising amount of the connotative power of film depends on this ‘cinematic shorthand’ of metonymy — that is, a figure of speech in which an attribute of something is used to stand for the thing itself, such as ‘laurels’ when it stands for ‘glory’ or ‘brass’ when it stands for ‘military officers’ — this use of associated detail to evoke an idea or represent an object. Our understanding of how a film means and how it directs our attention towards its meaning can be greatly enhanced and complicated merely by bringing this associative resonance of the cinematic image to the level of our awareness.

3. Lolita (1962) — Temptation and at the End of it All … Desire

We begin with the first lens of film reading and consider what the camera frames into our view through a look at Kubrick’s 1962 film Lolita. This was the film in which Kubrick began to develop his signature style of long, leisurely paced scenes that force the audience to step back and consider the overall setting and story, rather than getting caught up in the emotion of the scene itself. Kubrick felt this was the style that best suited Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial story, and also helped manoeuvre it around the strict censorship standards of the time. What we notice in Kubrick’s command of the camera as director is the way he not only shows us the images on the screen, but communicates rather subtly that he knows what we are watching and knows why we are — we are being watched as we watch.

Filmed in 1962 directly after completion of Spartacus, Kubrick shot most of the film in long master shots, sometimes up to ten minutes per take. Later, to give the film an even more literary quality, Kubrick and editor Anthony Harvey inserted fade-outs and fade-ins as scene transitions, with unusually long shots of black in between.

One aspect of film’s power is the illusion of looking in on a private world, the ordinary magnified to the scale of spectacle, from our vantage of security and anonymity. This juxtaposition of intensity and detachment suggests a role not merely as viewers, but as voyeurs. As Laura Mulvey notes in her essay, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, among the possible pleasures the cinema offers is that of looking itself. Who would deny that the magic of Hollywood style at its best has always arisen from ‘its skilled and satisfying manipulation of visual pleasure?’ Could it be, as Mulvey argues, that movies correspond not only to our needs for ego identification, but also to our erotic desire to see that which is private or dangerous or forbidden, to gaze at the other as object from our own position of security, thus having it both ways? Movie theatres as venues of projection: both of images and of repressed desires!

In a representative scene from Lolita, Kubrick draws the viewer into the temptation of the protagonist Humbert Humbert (played by James Mason) as he gazes upon young Lolita Haze (played by 14-year-old Sue Lyon) while in the continued company of Lolita’s mother Charlotte (played wonderfully by Shelley Winters). As the viewer is drawn to look upon Lolita Haze (an appropriate surname evoking a dreamlike quality of Nabokov’s character and well framed by Kubrick) swirling with her hula-hoop, we are brought to account for our ‘viewing’ by the burst of the flash from Charlotte’s camera. The dream/temptation bursts apart with — of all things — a burst of light that breaks the clouds or ‘haze’ away. Cinematically, we have been caught in the act of ‘looking’. A whole body of critical literature has developed out of this argument concerning cinema’s manipulation of the gaze (what theorist Jacques Lacan terms la regard) and how it reflects our deep psychological obsessions and the society that produces it. Throughout this film of temptation, Kubrick continues slowly to allow the approach of Lolita and Humbert, but akin to the classic tale of Tristan and Isolde they are continually pushed back over and over again leaving desire rather than consummation as the mark of the human dilemma.

Desire is an important aspect of faith. In a sermon entitled ‘The Depth of Experience’, theologian Paul Tillich states that it is desire that marks one of the essential aspects of our humanity and is one of the evidences of the imago dei — the image of god. For Tillich, it is our desire for what is truly desirable’ that drives so much of our activity (you can possibly hear Freud and his disciples chanting ‘Amen! Amen!’) but Tillich goes on to note that it is conversely desiring and finding disappointments in this life that ‘the truth of which does not disappoint dwells below the surface in the depth’.10 Here Tillich sees ‘depth’ as that meaning-making encounter that evidences our meeting with the divine or as Tillich states ‘the name of this infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of all being is God. That depth is what the word God means.’11

Kubrick’s films were manifestations of a search for ‘this infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of all being’ and calling the film reader to account as to that which they seek and desire and exposing the film reader to their own act of desire. One has only to look at Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange, which provides a number of instances of exposing the nature of desire as both a key to our downfall and also a mark of the divine spark in us.

4. The Shining (1980) — The Steady View of Fear

For a second lens — the camera’s angle on the subject — we now look at Kubrick’s 1980 retelling of Stephen King’s horror classic The Shining.

Directors can be said to fall into two camps — trackers and zoomers. The use of the zoom lens draws the subject of the film out to the audience and this is a technique often favoured by today’s directors. It is easy to do — merely change lens and re-frame the camera — and it doesn’t alter the set too much. The other option — use of the track whereby the entire camera is placed on a track and moved — is very laborious, as well as time and money intensive. One of the great effects of tracking however is the ability to draw the viewer into the shot in a way that doesn’t distort the image framed on screen. The reality of this use of the camera is that the viewer is ‘taken along for the ride’ as is seen in Kubrick’s turn to the horror genre in his 1980 film of Stephen King’s The Shining.

Prior to the mid-1970s, the only ways to move the camera within a closed-set scene were via a dolly apparatus or by having the operator hold the camera and walk around himself. The dolly allowed the camera extremely fluid movement, but required either an ultra-smooth surface or the laying down of tracks, plus several camera assistants to operate. Handheld camera shots, by their nature, tended to be somewhat unsteady, and were usually used to give a certain documentary-style effect (something Kubrick himself had done in his films on several occasions).

Then around 1974, a camera operator and inventor named Garrett Brown invented what he called the Steadicam. Essentially it was a small movie camera mounted onto a harness rig that could be carried and operated by one man, but which used a system of gyroscopes to keep the camera steady and the motion fluid. The result was a perfect hybrid of hand-held and dolly movement, and gave film-makers a new, very flexible tool for moving the camera.

However, the Steadicam was still considered an experimental device in 1978 when Kubrick decided to use it extensively for The Shining. In fact, Kubrick had the interior sets of the Overlook Hotel designed specifically with the Steadicam in mind, using only natural lighting and designing the corridors and rooms to gain the maximum effect from the device.

In a classic scene from The Shining, Danny Torrance (played by Danny Lloyd) is racing his Big Wheel tricycle through the hallways of the Overlook Hotel. As the viewer watches, we are placed in Danny’s viewpoint, tracking through the hallways from his low riding vantage point and moving with his reckless speed, quickly taking corners without any awareness of what lies ahead. Garrett Brown came up with extenders and other modifications to give Kubrick more flexibility, including a ‘low mode’ for shooting the scenes of Danny riding his Big Wheel throughout the hotel’s corridors.

Kubrick ended up shooting almost the entire film using the Steadicam, and The Shining was lauded for showing the device’s potential and making it a virtually standard piece of camera equipment from that point forward. As the set of the Overlook Hotel was constructed, Kubrick built the set — the rooms, the hallways, the angles of the windows — around how the Steadicam camera could be used to best advantage. What Kubrick demonstrates is a profound shift — he does not begin with a set then try to find a way to get the right shots through adjusting the camera technology to ‘fit in’. Rather, his universe begins with the principle of how things are to be seen — the angle of the shot first — then he builds the world around that.

In Kubrick’s universe, seen especially in The Shining and 2001, the camera angle provoked through the Steadicam tracking gives the viewer a steady view of fear: the anxiety of not being able to ‘see’ what comes around the next corner and thereby reminding us that in addition to desire, we as film readers must acknowledge the nature of fear and that unlimited space does not solve this but in many ways makes us realize how little we do ‘know’ and apprehend. Jeff Smith, in an article entitled ‘Careening Through Kubrick’s Space’12 notes that Kubrick’s use of space and how he fills the screen in his shots, for example in The Shining’s reduction of ‘environment’ to a particular place — a huge empty hotel cut off from human contact — and the elimination of 2001’s visual expansiveness in the middle section of the film in the space journey — both leave a ‘space’ so that the astronauts, whether on Earth amidst the open country or on a spaceship in the vastness of space, have no universe except their claustrophobic hotel/spaceship. The huge hotel and the large spacecraft Discovery are still not big enough — relationships begin in uneasy balance and gradually break down into menace and terror. What Kubrick proposes through his use of infinite space is that freedom is not found in lack of boundaries. Ironically, it is the seeming infinite space that is both physically and psychologically imprisoning for the winter occupants of The Shining and the space travellers of 2001.

In The Shining , the many doors of the Overlook open only onto more hotel, and the mirrors, deceptively breaching or enlarging space, ultimately turn one’s view inward and collapse the prospect of space back onto itself: the equation of space and the self in a paradox of identity tracing a line back to Narcissus. This is not the Interior Castle of St Theresa of Avila where through the many rooms and water wheels one finds a unifying embrace from God. Maybe the greatest fear is that we are truly isolated — that around each corner is another corner and another hallway and we have been ‘abandoned’ to our fears.

In other words, The Shining depicts a chaotic and relativistic universe devoid of higher agencies, one whose very size and emptiness infuriatingly underscores human limitations and forever condemns humanity to endure her own grotesque self. According to philosopher and mystic Simone Weil ‘we fly from the inner void, since God might steal into it. It is not the pursuit of pleasure and the aversion for effort which causes sin, but fear of God. We know that we cannot see him face to face without dying, and we do not want to die.’13 With God displaced, the weak and conflicted self comes to the centre position — many of Jack Nicholson’s shots in The Shining as we see him slowly slip into insanity are framed in the centre of the screen and fill most of the view — doomed to the endless deceptions of its own doors and mirrors. Toward the middle of the film, Jack makes a devil’s pact — stating he would give his soul for just one drink — which materializes the demons of the Overlook and brings the long- faded ghosts back to life. The devil’s pact offers no reward in a universe where certainty of knowledge is not possible. Man defines himself existentially only by his own dehumanizing actions — hence Jack’s ultimate reduction to pure act, and his likely readiness to anoint yet another as having ‘always’ been the caretaker.

This is a theme through much of Kubrick’s work — the loss of humanity and the search for some ultimate ‘meaning’ which, in the end, will only remove us from humanity at large. As seen in The Shining and 2001, HAL and Jack Torrance are obsessed about their ‘missions’ or ‘jobs’ — HAL with his ‘mission’ and Jack with his caretaking contract with the Overlook (and, by extension, with his pseudo-job of writing his book). Just as HAL says to Bowman ‘this mission is too important for you to jeopardize it’, Jack goes ballistic whenever it is suggested that the family leave the Overlook (and also when Wendy interrupts his ‘writing’). What is lost in embrace of one’s mission or vocation as a singular focus is ultimately one’s humanity. For both HAL and Jack, the inward turn towards an all-consuming ‘mission’ leaves them stripped of their possible humanity and care for others — in short, finding only isolation and fear.

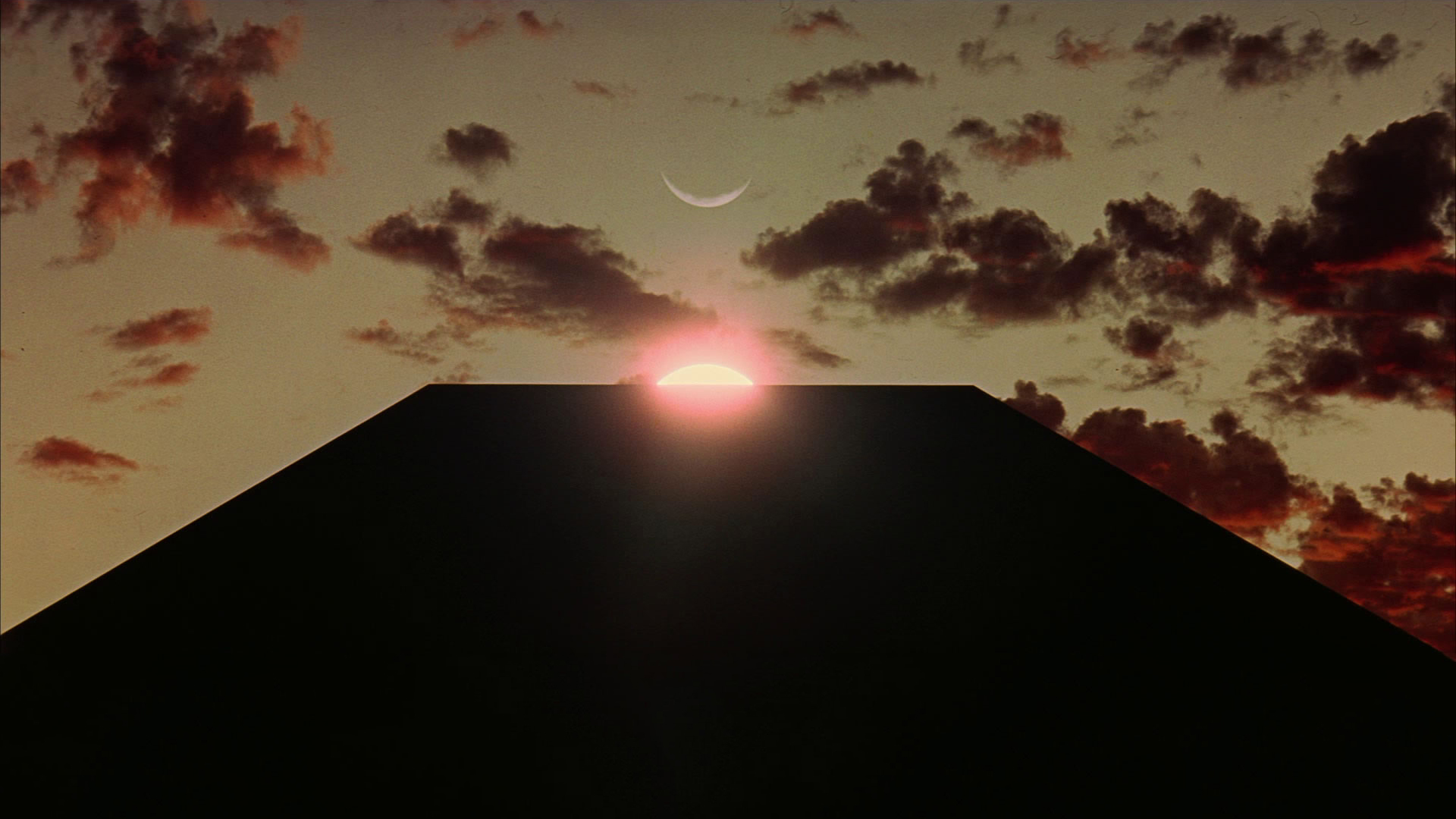

5. 2001 — An Agnostic Prayer

For our third lens for film reading — how camera shots tend to acquire meaning when they are seen in relation to other shots — we will reflect on the nature of the jump-cut technique in respect to 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In a recent documentary looking back at Kubrick’s work, Christiane Kubrick, Stanley Kubrick’s widow, spoke of 2001: A Space Odyssey as Kubrick’s ‘agnostic prayer’. Upon its initial release, the Vatican contacted Kubrick and invited him to come for a special showing of the film. Christiane Kubrick said that, as the images of the film filled the ancient wall of St Peter’s where the movie was being viewed, Stanley smiled and said ‘now I am beginning to understand my religion — this is an agnostic prayer, a plea for the “something” that must be out there somewhere’.

Kubrick was often pressed to interpret his work — as though to give an author’s read of the film as text that would somehow be authoritative. With regard to his 1968 sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey, he responded in this way:

How could we possibly appreciate the Mona Lisa if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: ‘The lady is smiling because she is hiding a secret from her lover.’ This would shackle the viewer to reality, and I don’t want this to happen to 2001.14

Ultimately, as Christianity looks back over its shoulder to its origins and finds at the heart great disruption — creatio ex nihilo, floods, famine, captivity, warfare, crucifixion and resurrection — moments of certainty seem to give way to kenotic emptying, books get consumed by prophets, feet of clay turn to dust and dust gets spat upon in order to overturn blindness for sight. Religion, time and time again, peers into the primeval chaos.15 Chaos is the beginning to which, in the great Romantic traditions, we ultimately return. For anthropologist Clifford Geertz, religion — conceived in terms of religious symbolism — negotiates ‘at least three points where chaos — a tumult of events that lack not just interpretations but interpretability — threatens to break in upon man’.16

2001: A Space Odyssey was and is such an event — a tumult of events that lack not just interpretations but interpretability — that draws the viewer into a journey of epic proportions. The fact that David Bowman’s ship is named Discovery should not be lost on us.

One thing immediately noticeable about 2001 is just how much of a true ‘film’ it is — it is a vision that brings its narrative forward in a visual linguistics — making iconic connections that deepen language beyond utterance into image and experience. One technique Kubrick uses in the film is an editing technique known as ‘jump cut’ — making immediate leaps from one point of reference in time and space to another that enable him to move through millennia within a split second while maintaining continuity. The scene that transitions from the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence of the film to the ‘Dance of the Stars’ is such an instance.

As Paul writes in 2 Corinthians, such a notion is deep within the Christian story:

all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another . . . For it is the God who said, ‘Light will shine out of the darkness’, who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ.17

2001 operates as a journey in a truest sense of calling and transformation from one degree of glory to another — a calling to go as Abraham is called to go but not necessarily told where. The forming of the journey is what gives it meaning — not a map given beforehand, but footprints along the way that show that one has moved from somewhere to somewhere else, creating a ‘poetic cartography’ where one can orient oneself and be invited to search for the nexus of the subject and the sacred — to touch the wounds of the past and truly to believe. One of the many narrative threads throughout this ‘agnostic prayer’ of Kubrick is that something is out there — that there are connections of intentionality in the creative story of our universe that show ‘something’ going on — not a random haphazard milieu per se — but connections and movement toward something. The desire we have for something more — something of infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of all being — is hoped for and like the announcing angels of the incarnation, this hope for the infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of all being can be a solace of ‘Fear Not’ as we fear what lies around the bend. In some ways, Kubrick’s films are worth reading deeply for the simple fact that they read humanity’s desires and fears so well, yet map out a way that has no boundary or ‘edge’ that would announce the end of the world or a limit to the universe that creates a sense of beginning and end, but is fully enclosed and three-dimensional, moving itself in the fullest breath, depth, and height of time and space18 as one who comes unannounced — akin to the monolith that reappears and calls out as an evangelion — bearing gospel or good news that can be a blessing and terrifying in the same instance.

Meister Eckhart has aptly characterized true encounter with the divine as an ‘un-becoming’ (‘Entwerdung’). As Eckhart states ‘when I reach the depths of divinity no one asks me whence I come and where I have been, and no one misses me, for here there is an un-becoming’.19 Kubrick’s films end as an un-becoming either with the apocalyptic scope of the birth of the Star Child in 2001 or freezing of Jack Torrance in the everlasting maze of the Overlook in The Shining — or the un-becoming of the self as seen in Lolita through to Eyes Wide Shut. Yet it is in this kenotic un-becoming that we can begin to ‘open the pod doors’ to what Kubrick worked for.

NOTES

1. American Academy of Motion Pictures and Film database — www.oscars.org

2. James Monaco, How to Read a Film: The World of Movies, Media, and Multimedia: Language, History, Theory, 3rd edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 15.

3. Christian Metz, Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema, reprint edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990, p. 5.

4. There have been numerous studies of Kubrick’s work from many different angles, notably Luis Garcia Mainar, Narrative and Stylistic Patterns in the Films of Stanley Kubrick, London: Camden House, 1999; Michel Chion, Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey, London: British Film Institute, 2001; Thomas Allen Nelson, Kubrick: Inside a Film Artist’s Maze, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982. However, there is still a lack of critical reflection upon the theological concerns related to Kubrick’s filmic poetics.

5. See Rudolph Otto, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational, London: Oxford University Press, 1950.

6. Mary Douglas, Implicit Meanings, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1975, P. 76.

7. Marshall McLuhan, (with Quentin Fiore), The Medium is the Massage, New York: Bantam, 1967, p. 26. McLuhan’s most vivid description of the ‘technological sensorium’ is provided.

8. Babara De Concini’s article ‘Seduction by Visual Image’, The Journal of Religion and Film, 2(3) (December 1998): Section 1.

9. De Concini, ‘Seduction by Visual Image’, Section 1.

10. Paul Tillich, The Shaking of the Foundations, New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1948, p. 53

11. Tillich, Shaking of the Foundations, p. 57.

12. Jeff Smith, ‘Careening Through Kubrick’s Space’, Chicago Review, 33(1) (Summer 1981): 62-73.

13. Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1952.

14. Gene D. Phillips, Stanley Kubrick: A Film Odyssey, London: Popular Library, 1977.

15. This is the view of religion as it is investigated by twentieth-century anthropologists. For Mary Douglas, a ‘person without religion would be the person content to do without explanations’ (Implicit Meanings, p. 76).

16. Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books, 1973, p. 100.

17. 2 Corinthians 3.18; 4.6 NRSV. David Ford in his recent book, Self and Salvation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, has an extended reflection on this notion of ‘facing’ in relation to the figuring of Christ.

18. I am seeing this notion of ‘poetic cartography’ as akin to the attempts put forward by women mystics such as Theresa of Avila. See E. Ann Matter, ‘Internal Maps of an Eternal External’ and Laurie Finke, ‘Mystical Bodies and the Dialogics of Vision’, in Ulrike Wiethaus (ed.), Maps of Flesh and Light, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1993, pp. 28ff.

19. Cited by Rudolf Steiner, Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age, New York: Garber Communications, 1996, p. 80. Originally published in 1923 as Die Mystik im Ausgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens und ihr Verhältnis zur modernen Weltanschauung.

* * *

What is Auteur Theory?

What role does the director of a film play in the overall film? This is a point that has been greatly debated. Auteur theory is the school of thought that argues that for some film productions, the role of the director is not only central to understanding the overall meaning of a film but that it is vital. Auteur is French for ‘author’ and the politics of auteur, or politique des auteurs, were first stated by director Francois Truffaut in his article ‘Une certaine tendance du cinema francais’ in Cahiers du cinema (Notebooks on Cinema) in 1954. Truffaut postulated that one person, usually the director, has the artistic responsibility for a film and reveals a personal world-view through the tensions among style, theme and the conditions of production. In short, auteur theory argues that films can be studied like novels and paintings as a product of an individual artist. Truffaut’s pronouncement helped defend the Hollywood system of film-making in the late 1950s against France’s popular criticism. Truffaut maintained that the work of an author could be found in many Hollywood films and it was the quality of the director that was the measure of the work, not necessarily the work itself.

Examples of those film-makers often referred to as auteurs include Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchcock and Woody Allen.

Most people now refer to ‘new auteur theory’. In current film criticism, there is widespread acknowledgement that films are not the product of merely one auteur or creator but collective efforts. Although the director still receives most of the credit for the voice of the film, many of the current directors who are considered auteurs use the same cast and crew for most if not all their films. This raises the question, if the crew is the same in every film, is it possible to distinguish the voice of the director from that of the collective (screenwriters, actors, production designer, all those responsible for creative decisions)? Contemporary auteurs such as the Coen brothers, Wes Anderson and Christopher Guest almost always use the same creative team. New auteur theory holds that those responsible for the creative decisions that influence the form of the film are always the same group of individuals.

SOURCE: Cinéma Divinité. Religion, Theology and the Bible in Film, Edited by Eric S. Christianson, Peter Francis and William R. Telford, 2005