Michael Cimino is a 1963 graduate of Yale University who entered filmmaking as a director of documentaries and industrials before turning to screenwriting as a way to break into feature directing. His first film, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974), came about through the insistence of Clint Eastwood, who wanted Cimino to direct him on the strength of his rewrite of Magnum Force (1973), the second Dirty Harry film. Thunderbolt and Light foot was not critically well received, but has since attracted a loyal following. Jeff Bridges was Oscar-nominated for Best Supporting Actor, an early spotlight on Cimino’s obsessive interest in character and performance.

The next few years were spent writing and doing pre-production work on a half-dozen original and adapted screenplays, but again and again Cimino was frustrated in his attempts to put any of them before the cameras. Then, rather quickly. The Deer Hunter (1978) came together for him. An extremely ambitious film, it was one of the first attempts by an American filmmaker to depict and confront the horror of Vietnam. The Deer Hunter was one of the most important films of the Seventies, and won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director. Cimino now had the clout to begin a long-cherished film, The Johnson County Wars, which mushroomed into the epic Heaven’s Gate (1980). Reams have been written on that ill-fated venture, most notably Steven Bach’s Final Cut, yet despite its excesses, Heaven’s Gate is full of stunning images and has begun to live down its notorious reputation through cable TV and homevideo screenings. For his next two pictures—Year of the Dragon (1985) and The Sicilian (1987)—Cimino turned to the crime genre.

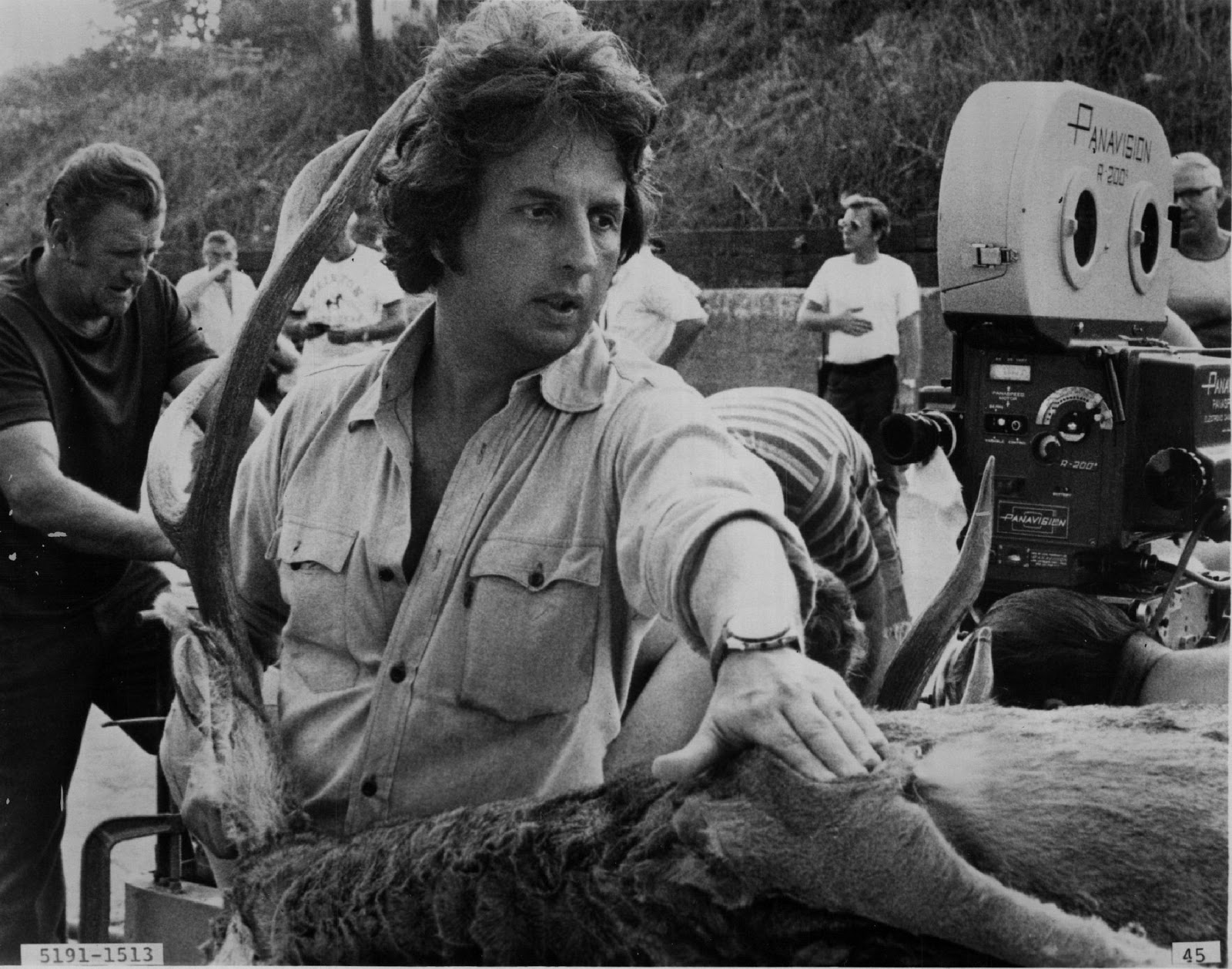

This interview with Michael Cimino by Mark Patrick Carducci took place on the set of The Deer Hunter in Mingo, Pennsylvania, in July 1977. Carducci spent three days with the production unit, waiting for his opportunity to speak at length with Cimino: “On the afternoon of the second day he came over to me and suggested we do the interview during the ride back to the Holiday Inn we were quartered in that evening. When Cimino turned around to look for cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond to frame and light the next set-up, he could not find him. An outburst of creative temperament had transpired between Vilmos and the script girl while Cimino and I spoke, and Vilmos had walked off the set in anger. For a moment, Cimino seemed lost. His gaze weakened and for an instant he appeared near exhaustion. I sensed it might be best to take a walk outside, and did so. But before going out I glanced back. Cimino had climbed behind the massive Panavision camera and was himself framing an upward-angle closeup. At that point he was alone on the set, the only man in the room.”

* * *

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: I understand that you were not initially decided on a career in film.

MICHAEL CIMINO: No. I was really more involved with the plastic arts—architecture, art history. That’s what I had done most of my undergraduate and graduate work in. It wasn’t until after I got out of school that I decided I wanted to become more involved with film. It was kind of an abrupt thing.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: What made you begin writing?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Joann Carelli, the associate producer on The Deer Hunter, actually talked me into it. I’d never really written anything before. I still don’t regard myself as a writer. I’ve probably written about thirteen or fourteen screenplays by now but I still don’t view myself that way. Yet, that’s how I make my living.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Is The Deer Hunter a personal work?

MICHAEL CIMINO: As it happens, the screenplay is very personal. When I was growing up I had a number of very close friends who were Russian Jews. I was influenced a great deal by them. Certain things stayed with me. For instance, I was best man at one of their weddings, a Russian Orthodox wedding. There is a wedding very similar to that one in the film. When I was writing documentaries and industrials I came to Pennsylvania for U.S. Steel. That was my first look at a steel mill and I spent quite a lot of time there. That also made an impression on me. Lastly, I served in the army as a medic attached to a Green Beret unit that was taking advanced medical training in Texas, and I got to know and like those men very much. All those things are a part of The Deer Hunter script.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Is this the first opportunity you’ve had to draw upon your own life as source material?

MICHAEL CIMINO: No, I would say that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is similar to The Deer Hunter in that respect. The things that interest me are present to a degree in both films. Thunderbolt, however, masquerades more easily as a less personal work.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: How long did The Deer Hunter screenplay take to complete?

MICHAEL CIMINO: It went fairly quickly once I began it. A peculiar set of circumstances attended the start of the project. I had spent a year and a half at Paramount working on something called Perfect Strangers, an original, a love story with a political background. By way of easy description it bears some resemblance to Casablanca (1942), involving the romantic relationship of three people. Someone called it a romantic Z (1969). I was very close to doing it. In fact, we’d already shot two weeks of pre-production stuff, but because of various political machinations at the studio, the project fell through. This was just before David Picker left. He was the producer. There were internal difficulties, that’s all. Nevertheless, I’d spent a year and a half of my life on something. It had been a difficult time. My father passed away while I was writing the screenplay. I kept working, spending the next two and a half years writing something I liked very much with Jimmy Toback. It was called The Life and Dreams of Frank Costello, based on the man some people have called the founder of the modern Mafia. We got a good screenplay together but again, the studio, 20th Century- Fox in this case, was going through management changes and the script was put aside. Almost simultaneously, I finished an original called Pearl for Fox. It’s almost a musical, based on the life of Janis Joplin. I was working with Bo Goldman on that one and we were doing a series of rewrites. I also had an agreement with United Artists to adapt The Fountainhead. All these projects were in the air at once. I postponed Fountainhead until we had a first draft on Pearl, then after meetings with Jimmy began Frank Costello.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: You seem to write quickly.

MICHAEL CIMINO: Sometimes. Other times it’s quite slow and painful. The Fountainhead was that kind of script. The book itself was almost 800 pages and just reading it takes a considerable amount of time. Also, making it a contemporary story meant that there was a lot of new work that had to be done. It was very time-consuming. Plus when you work from a book with that kind of reputation you put more pressure on yourself. Silent Running (1972) was very quick. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the first rough draft, I remember quite clearly doing in six weeks. I polished it over the next two months. Costello took a long time because Costello himself had a long, interesting life. The selection of things to film was quite hard. The Deer Hunter, and here I’m talking very rough first draft, took seven or eight weeks.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Do you normally work out the script in detail in your head before committing it to paper?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Sometimes. But I don’t claim to be a trained writer. I learned about writing principally from studying acting. 1 probably learned more about it there than any place. I just can’t draw a general conclusion from your question.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Wouldn’t you say it’s beneficial to know where you’re going before you get too far into it?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Ummm … I suppose. I suppose that’s a reasonable thing. Sometimes I have a vision of the whole thing. That’s happened. But in many cases it hasn’t. Often, one just plunges in and flails around in the dark, trusting one’s instincts and intuition. Both are valid ways to work.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: What was it like collaborating with John Milius on Magnum Force?

MICHAEL CIMINO: We really didn’t work together. It was John’s initial script, not mine. He wrote what amounted to a first draft, which he couldn’t finish because he’d gone off to direct Dillinger (1973). I was asked by Clint Eastwood and Warner Brothers to pull the script together. At first I said no. I didn’t feel used to the genre. But they were very persistent and finally I took it on with the understanding that I don’t turn in any pages, I just turn in the script when I’m finished. That’s the deal I’ve made on everything I’ve written so far.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Do you establish your own personal quota?

MICHAEL CIMINO: There have been days where I’ve felt really great completing five pages. But I’m usually slower than that.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Why did you choose Vilmos Zsigmond as your Director of Photography on The Deer Hunter?

MICHAEL CIMINO: I think he’s an extraordinary cinematographer. His reputation is there. We’re trying to do a very difficult thing on this picture—shooting summer for winter. We’re also working in real places. In the eastern United States alone we’re shooting in seven cities just to create the look of one small town. There have been times when we weren’t able to move the camera fifteen degrees in either direction. We’ve got interiors and exteriors two and three hundred miles apart. We’ve had to strip trees, brown grass, defoliate huge areas. To take the long way around in answering your question about Vilmos, I felt that given all of these things, we needed somebody special. Once again, Joann Carelli was the one who suggested Vilmos to me.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Have you and he worked out a visual attitude for the film?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Yes. I would call it highly stylized. Some might call it naturalistic, which it is not. It’s only natural in the sense that we’re shooting location.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Zsigmond is noted for a very low-key, muted kind of lighting style.

MICHAEL CIMINO: We’ve gone for more than that. There’s a whole approach to the way of shooting, especially of exteriors. I happen to like large exteriors, exteriors that have scope. I like a sense of figures in a landscape, of seeing the size of the landscape in relation to the people. If it’s a large landscape, as big as a steel mill that’s twelve miles long, then I want to see the scale. It becomes an element of the film with its own dramatic presence. Not to show it would be to waste it. Vilmos and I talked at great length about going for that.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: How heavily are you relying on Zsigrnond for composition?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Because of my background I’ve always been very concerned with that. For instance, when it comes to the design of the sets, I get extremely specific.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: The Welsh’s Bar set is something amazing. What a sense of reality.

MICHAEL CIMINO: l don’t know how carefully you’ve looked at it, but if you study it closely you’ll see that there are practically no parallel lines in it. It’s designed that way to enhance the notion of age, of the warping of the wood in a building as it gets older and older. This is true of the beams in the ceiling, the moldings, door frames, everything.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Have you scripted your angles and framing, or are you giving Zsigmond some latitude in these areas?

MICHAEL CIMINO: On the first screenplay I ever wrote I tried to lay out the way it would be shot. In my view it’s a mistake. When you sit down to write a screenplay, in most cases you haven’t even seen the locations yet. All you’re doing is cutting yourself off from the possibilities of things you might find. Anything that limits you before you start is a mistake. It’s quite mysterious, anyway. What I mean is, when you write a film, you envision a place that is a composite of things you know. Then you go out and somehow find that place. It exists, it’s waiting for you, and if you’re persistent enough, you will find it. I’ve only found a couple of cameramen whose way of seeing things coincided with my own. Once you’ve found someone like that you can stand back and become more involved with other things, especially performance. You can work with the actors. The first day of shooting required a large set-up with hundreds of extras and all the principals. It was then that l knew I was right about Vilmos. We were on the same wave length.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: I’ve been told you’re a few days behind schedule. What effect is this having on you and the cast and crew?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Naturally, you always care about being ahead or behind. It’s nicer to be ahead. You work as hard as you can every day and try and maintain a certain level of quality. It becomes a daily battle.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Francis Coppola has said that the actual shooting of a film is the most trying time for him. Do you find this to be true?

MICHAEL CIMINO: I would say so. When you’re writing there’s much more control. You only deal with your own energy level. While shooting you must deal with the energy level of a hundred people and not everybody is up at the same time. It’s up to the director to keep willing it through. George Cukor said, “Never tire, never wilt.” You’ve got to keep fighting for quality. That’s Bobby De Niro’s attitude as well. He feels there’s always room to improve, there’s always a way to do it better. He attempts to fill every moment and that’s what should always be striven for, particularly in a picture like this, which is about people, their relationships and the nature of courage and friendship. There’s a great deal going on between the characters. I’ve got eight or nine first-rate actors, all of whom must receive attention. It’s a great relief to have Vilmos, to have an area I’m completely comfortable with. Between me, Vilmos, and Bobby, all of us pushing for perfection, things can be very trying. It can wear people down. A crew likes to move at a certain pace—quickly. You try to move as quickly as possible but there are times when you simply cannot do that. And it’s in those very moments that it’s easiest to let go. You can succumb to the pressure of having all those people standing around. You can panic and allow them to be the overriding factor. Of course, you must always maintain a certain responsibility to budget and schedule as well. It’s very hard.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Parts of The Deer Hunter take place in Vietnam. You apparently feel Americans are ready to confront that war in their entertainment.

MICHAEL CIMINO: I think it’s time. I’m sure, for instance, that Francis’ Apocalypse Now (1978) will be a hugely successful film.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: I read recently that one of the reasons Apocalypse Now has been so long in the making is that in working with generals and other army personnel, Coppola’s ideas about the mentality of those men were challenged. What began basically as an anti-war tract suddenly lost its focus as certain myths he held to be true were exploded.

MICHAEL CIMINO: That’s interesting because it’s one of the points of The Deer Hunter. People ascribe certain political leanings to combat troops like the Green Berets, which in fact most of them don’t have. Many guys join those kinds of outfits for the adventure or other non-political reasons. After going through the formidable training they have to endure, they naturally develop bonds with one another which then become the primary thing. War becomes a question of protecting your friends, people you care about. Their combat experience has more to do with that than anything else. If I had to go into combat tomorrow. I’d want to go in there with guys like that, not a bunch of weekend warriors from some National Guard unit.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: You’ve chosen Peter Zinner as your editor, an editor on Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974). What challenges do the two of you face?

MICHAEL CIMINO: This will be an unusual picture from that standpoint. Many of the exterior scenes are done in long, uninterrupted master shots.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Why is that?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Part of the reason is to preserve the relationship between the characters and their environment, to remove those interruptions that prevent you from feeling that relationship. Most editors hate it because it locks them into using the shot. There’s no way they can alter it. This makes it all the more important for me, as the director, to concentrate on the performances. They can’t be altered, either. When you’ve got five or six people m a single shot like that, each performance needs to be right. It’s not easy to shoot this way, but when it works it’s quite exciting.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Will the Vietnam sequences, which you arc filming in Thailand, be shot or lit differently from the footage taken in the States?

MICHAEL CIMINO: It will be very different. There will be more abrupt cutting. And just being in Thailand will impose differences in our visual style, since the light and colors of the place are not the same.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Who are some of the directors whose films you respond to most?

MICHAEL CIMINO: I admire Francis’ films very much. I must say I have a great feeling for Sam Peckinpah’s work. Even in films of his that people don’t much admire, I find there’s always a certain humanity, a concern for people.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Then you must have liked Junior Bonner (1972).

MICHAEL CIMINO: l thought it was wonderful. I really love that picture. Sam understands about life and death. He’s one of the few American filmmakers who does. There’s a scene in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) where Slim Pickens gets shot. He’s sitting on a rock at the edge of a lake and his wife is sitting on another rock across from him. He’s dying. There are no words, but it’s a magnificent scene. The unspoken understanding between the two of them is beyond description. Or take the scene in Junior Bonner on the back stairs behind the bar between Robert Preston and Ida Lupino. I was terribly moved by it. In even the least of Sam’s work there are moments like that.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: What European directors would you cite?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Godard, certainly. There was always some new direction he was going in. Visconti, for the same reason. Fellini, particularly the early films. Back to American directors, John Ford was a strong influence. His films have real emotion. And I love Vincente Minnelli’s work—his attention to detail, especially in the musicals. There are so many I can’t single them all out. Then there are some brilliant American still photographers who I feel a great affinity for, men like Walker Evans and Robert Frank. They’ve captured this country in much more vivid ways than our filmmakers have. Eugene Smith, for instance, documented the city of Pittsburgh in still photographs. When I think about it I realize these men have been a stronger influence on me than the films I have seen. I haven’t seen any American films that communicate the very special nature of certain portions of this country. It’s what moves me to find locations like the ones we’re shooting in now, to get those images in a film.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Are you much concerned with how your finished films are received?

MICHAEL CIMINO: A part of me worries about that, I suppose. The part of me that is connected to deal-making, those elements that go into getting the money up for this kind of thing. I would like The Deer Hunter to be a successful, mass appeal film. That would be nice. But I do not think about that possibility on a daily basis. The actual work is too hard. Stravinsky said, “When you work you look down, you don’t look up.” So you put down one brick at a time and eventually you’ll find yourself on top of a building. Also, you try and learn what is hardest in life to learn—a way to extract a measure of enjoyment from the doing of the thing. But if all one does is look up, one can become discouraged. Surely if one worries every day about what will be happening six months from now, the results you’ll be getting every day will suffer. As regards an audience’s reaction, my major concern is closely related to the film itself. Are things clear? Are the things the actors are doing understandable? Arc their intentions clear? You know, you can reach a point while writing a script where you become lost and you wonder whether the script makes any sense at all. It’s then that you must keep going. If the idea is sound to start with, you will get past that point. To use a famous phrase Clint Eastwood uses, “You must will it through.” That’s the only way.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Have you made any changes or new discoveries in the screenplay of The Deer Hunter since filming began?

MICHAEL CIMINO: One of the things we were all surprised at was the love which has developed between Bobby’s character and Meryl Streep’s character. It’s become marvelous, much more vivid than I’d imagined it. What did this was seeing how well the two of them play together. They’re so good, so exciting.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Does DeNiro “feed” other actors or does he derive energy from them?

MICHAEL CIMINO: It’s a mutual process. Bobby uses everything, where it’s applicable; and, by virtue of the way he works, he sets a certain tone which sparks things.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: It is true you wrote the lead role with him in mind?

MICHAEL CIMINO: No, it is not. I don’t do that. The chances of getting a particular actor are always quite remote. I make a conscious effort not to form a preconception of the character in this respect. I like to stay wide open.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: There are writers who believe that casting in your mind’s eye while you write helps you write more easily.

MICHAEL CIMINO: I’ve never found it to be of any help. The only thing I can say that has helped me iti writing is the experience of studying acting. That was and is enormously helpful. I would like to know a hundred times more about acting than I do. You never really feel you know as much as you should and yet there comes a time when you have to just jump in and do a thing. That’s true in every field today. Unfortunately, we no longer have a master and apprentice system, as once existed. The opportunity to perfect one’s craft from the ground up is largely non-existent.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: I understand what you mean. Look at the scarcity of good animators today or the scarcity of good matte painters.

MICHAEL CIMINO: And that’s true in acting as well, which makes someone like Bobby so rare. He is a craftsman, a professional. He believes that acting is something to work at, that a special performance is not entirely an accident. Bobby lives that. He’s his own best example.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: There’s a story I’ve heard from guys in various crews that Gordon Willis is largely responsible for the success of the first Godfather film. I can’t buy that.

MICHAEL CIMINO: I suppose that’s a case of the conductor thinking he composed the score after conducting it a few times. The whole business of making a movie is a rather strange affair. To bring a project to the point where it can be shot can involve literally years of effort. You write something, struggle and sweat over it, cast it, and then people like the cameraman, crew members, and the editor come in and work on it. They are very lucky. They work only on the projects that go, only seeing the tip of the iceberg. The writer-director lives with a particular project for a couple of years before and a couple of years after them. To him it represents a major chunk of his working life. Gone are the days when a guy like Victor Fleming could do The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind in the same year (1939). Each of those things would take five years apiece today. It’s a bittersweet thing. In the end, I have no idea why anyone would want to take The Godfather away from Francis.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: To read some of the reviews of your own Thunderbolt and Light foot, many critics seemed to want to take that picture away from you.

MICHAEL CIMINO: Very few of them realized that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was a first feature. It was passed over, written off as just another Clint Eastwood movie. This put my ego out of joint a little bit, but I got over it. In Europe, for some reason, the critics were able to see past that easy characterization. In England, particularly, I felt very good about the way the film was received. They show it at the National Film Theatre all the time. It was also very gratifying when Jeff (Bridges) got his second Academy Award nomination for his role. It meant that, within the industry at least, people had seen the picture and appreciated it.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Silent Running, for all its problems, was certainly a signpost in the light of the current resurgence of interest in science fiction cinema. When did effects genius Doug Trumbull enter the project?

MICHAEL CIMINO: Doug was the first person involved. He developed the original premise, which was not finally what the film was about. Doug’s was a straightforward, simple story about a guy who runs a space shuttle, who gets fired from his job, and out of revenge takes off with the ship. The screenplay had gone through drafts at the hands of a whole line of writers and they were already committed to building the sets when the producers called me in. They flew me to California and I was holed up at the Bel Air Hotel for two weeks working out a new story.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: Many people think of science fiction as frivolous at best, idiotic at worst.

MICHAEL CIMINO: I didn’t think of Silent Running as science fiction. My storyline had a strong enough premise that it could have been set anywhere. That’s one of the problems with most filmed science fiction—they depend too much on the liberties you can take with the genre. Science fiction really requires incredible discipline because you set the ground rules yourself. My concern was with writing material that didn’t use the fact that it was science fiction like a crutch. Unfortunately, after I left they decided to rely more on the technology, the special effects, and the gadgets.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: For me the film’s major flaw lies in the extremity of Bruce Dern’s action in killing his fellow officers in order to preserve the last of Earth’s forests.

MICHAEL CIMINO: That was the problem. My contribution to Silent Running was in providing the notion of the forests, saving the forests. But you have to know that the other guys were career men. Things like promotions were real to them. The survival of the forests didn’t mean anything. In the finished film their blase reaction is almost gratuitous, making Dern’s action seem unmotivated. It was supposed to be indicated that they had been disconnected from things like trees for so long that they no longer cared. Not that they were unthinking, unfeeling individuals, but that they’d simply lost contact. This tragedy was to have fueled Dern’s action. He was to have killed them as much in a rage against them as against a world, a system that could come to such a pass.

MARK PATRICK CARDUCCI: You are now directing your own screenplays. Would you ever again consider writing material for others to direct?

MICHAEL CIMINO: I don’t know the answer to that. I really don’t. Who knows? Maybe I’ll surprise myself.

Mark Patrick Carducci, “Stalking the Deer Hunter: An Interview with Michael Cimino.” Millimeter Mar (1978)

Republished in John A. Gallagher (edited by), Film Directors on Directing , pp. 37-47