by Pauline Kael

Hans Christian Andersen’s tear-stained The Little Mermaid is peerlessly mythic. It’s the closest thing women have to a feminine Faust story. The Little Mermaid gives up her lovely voice—her means of expression—in exchange for legs, so she’ll be able to walk on land and attract the man she loves. If she can win him in marriage, she will gain an immortal soul; if she can’t, she’ll be foam on the sea.

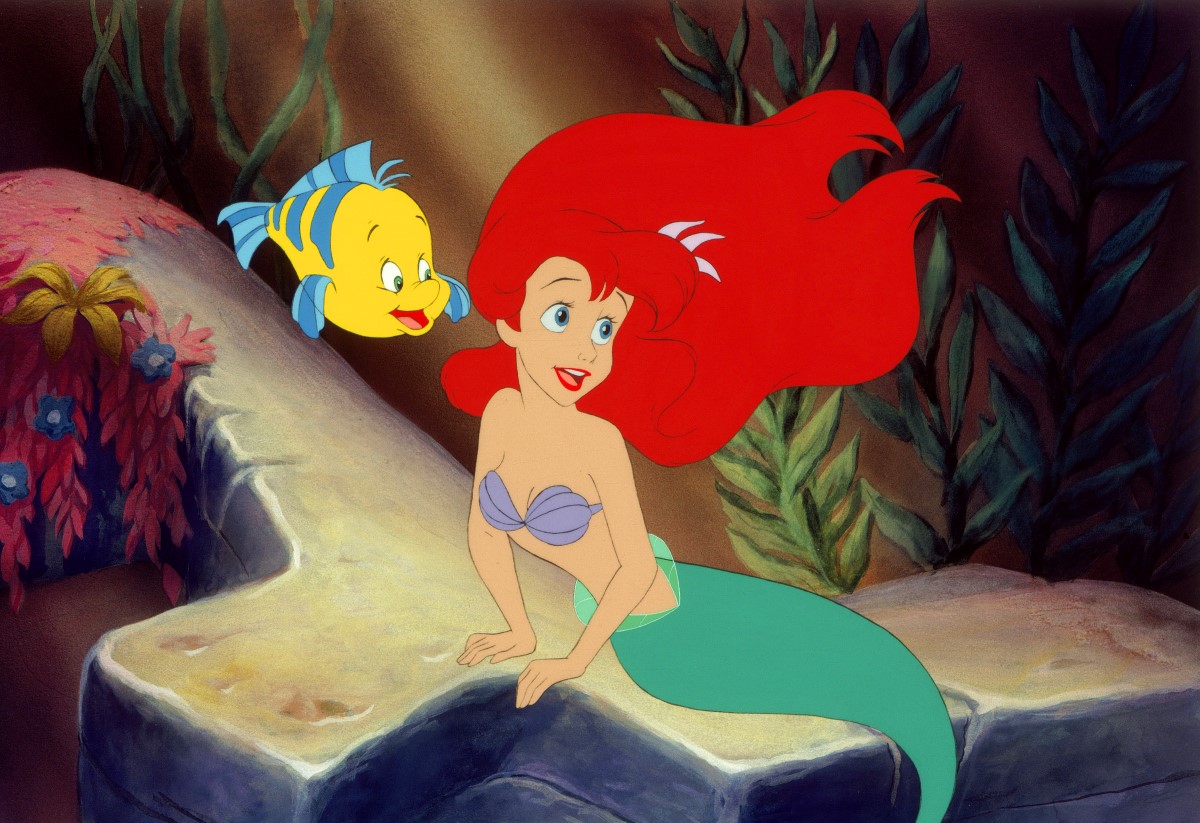

I didn’t expect the new Disney The Little Mermaid to be I Faust, but after reading the reviews (“everything an animated feature should be,’’ “reclaims the movie house as a dream palace,’’ and so on) I expected to see something more than a bland reworking of old Disney fairy tales, featuring a teen-age tootsie in a flirty seashell bra. This is a technologically sophisticated cartoon with just about all the simpering old Disney values in place. (The Faust theme acquires a wholesome family sub-theme.) The film does have a cheerful calypso number (“Under the Sea”), and the color is bright—at least, until the mermaid goes on land, when everything seems to dull out.

Are we trying to put kids into some sort of moral-aesthetic safe house? Parents seem desperate for harmless family entertainment. Probably they don’t mind this movie’s being vapid, because the whole family can share it, and no one is offended. We’re caught in a culture warp. Our children are flushed with pleasure when we read them Where the Wild Things Are or Roald Dahl’s sinister stories. Kids are ecstatic watching videos of The Secret of MIMH and The Dark Crystal. Yet here comes the press telling us that The Little Mermaid is “due for immortality.” People are made to feel that this stale pastry is what they should be taking their kids to, that it’s art for children. And when they see the movie they may believe it, because this Mermaid is just a slightly updated version of what their parents took them to. They’ve been imprinted with Disney-style kitsch.

The New Yorker, December 11, 1989