Dale Winogura’s review of Ken Russell’s The Devils describes it as a masterpiece, offensive yet profoundly impactful, and a powerful commentary on human cruelty and hypocrisy. The film, marked by Russell’s intense, unbridled cinematic style, is divisive, eliciting strong reactions of either deep appreciation or intense dislike. It’s not recommended for the faint-hearted, requiring viewers to have emotional maturity and a strong stomach. The review criticizes Russell’s adaptation of D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love as disjointed, while praising Billion Dollar Brain for its amusing and innovative approach. The Devils, based on Aldous Huxley’s book and John Whiting’s play, graphically explores religious hypocrisy in 17th-century France. The performances, especially by Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, are lauded for their intensity and conviction. Visually, the film is striking, capturing the dark era’s essence. The review acknowledges the film’s controversial nature and the need for viewer discretion, emphasizing its uniqueness and unforgettable impact.

… Offensive in a positive sense…

by Dale Winogura

“A mad animal. Man’s a mad animal.”

—Peter Weiss, MARAT/SADE.

No mincing words, Ken Russell’s The Devils is a masterpiece and one of the greatest motion pictures ever. It is also one of the most thoroughly offensive, repulsive, nauseous, and powerful assaults on man’s inhumanity to man and himself in cinema history.

Cinema of madness and insanity is an apt way of describing Russell’s method, and he applies it here with a force and intensity that vomits itself unbridled by convention. It exudes his personality with such relentless, uncompromising impact that the film is bound to be the most praised and damned achievement of Russell’s career. Either, one will hate, loathe, and deplore its living guts, or love it to absolute distraction. No middle-ground or indifferent stand can be taken with a film like The Devils.

Only those who can look beyond moral prejudice, and see into Russell’s fully, brilliantly achieved vision of mankind will appreciate the mastery with which he realizes his ends. No weak wills, hearts, or stomachs should see it, only those who can view cinema with an involvement in emotional experience, an objectivity of form in relation to content, and a basic maturity of mind should even be permitted inside the theatre.

Russell was not at home with the complex Freudian intellectualization and subtle sexuality of Lawrence’s Women in Love. His blatantly operatic vision and audacious technique was not merely unsuitable, it was obfuscating, pretentious, and unbearably boring both to Lawrence and Russell.

The Music Lovers was infinitely more adaptable to his unique methods of expression, his grandiose cinematic effects, and his feelings on man’s persecution. It was a near-masterpiece of stylized biography, using Tschaikovsky’s opulent music in splendid contrast with the insane grandeur of his life, but because it came more uncomfortably close to Russell’s persona than the relatively more comforting aesthetic distance of Women in Love, the critics summarily blasted it.

An earlier work of his, Billion Dollar Brain, is probably more satisfying and ingeniously made than any of the other Michael Caine-Harry Palmer films, or any of the James Bond epics for that matter. It was a funny, mad carnival of a spy satire, experimenting with suspense techniques like all get out, and climaxing in a magnificently outrageous parody of the ice battle in Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky. Russell played with the possibilities of the cinema like a child with a new toy, and it was an amusing, thoroughly amiable endeavor. But playing with the medium can only go so far, even when used in an appropriate context such as Billion Dollar Brain. In a work such as Women in Love, Russell’s anarchistic personality and technique games totally defeated the graceful qualities of D. H. Lawrence, and the result was predictably confused and disjointed, without any redeeming sense of flow, tempo, or subtlety.

In Aldous Huxley’s book. The Devils of Loudun, and in John Whiting’s play adaptation, The Devils, Russell has found the perfect outlet for venting his distorted vision. Based on true events in the year 1634, in France, it graphically depicts the religious hypocrisy and moral indignation that spawned the belief in spirits, demons, and the devil. With so much emotional restraint taught and exercised at the time, the explosion of immorality and decadence, even in the sacred confines of the church, was inevitable. Pent-up, unreleased emotions, unleashed under the pretense of the influence of witchcraft, brought about a series of depraved orgies and spectacles, defiling the holy ground of the Catholic church and all that it stood for at the time. Russell conveys this sickness and mental deterioration with unparallelled vividness and explicit candor; nuns stripping themselves naked and having intercourse with strangers; the howling, jeering mob watching the lurid circus of bachhanalia; and the accompanying ignorance of the ruling class to stop it and the profiteers from taking advantage of the ignorance and immorality of the masses.

Never before had I seriously considered the possibility of Russell being a genius, but The Devils must be the work of one, however insane. In spite of the film’s basic ugliness, it is a very moral film. By depicting the other, blacker side of human nature, the film is abstractly pro-religious, not against it as so many will obviously conclude. In viewing man’s vulnerability and past mistakes comes the illumination of a better, wiser future, and The Devils is shocking only because it forces the spectator to come to grips with this and to understand the means in which he may correct them. But the film offers no easy solution. It is a plea for sanity, understanding, love, and trust in a world that, even today, possesses ignorance and hypocrisy.

The Devils is not offensive in the same sense as Tony Richardson’s The Loved One, Michael Sarne’s Myra Breckinridge, or Cammell and Roeg’s Performance. These works were offensive not because of their subject matter, or even their peculiar, distasteful personalities, but because there was no strong binding of style or content, no maturity of form, and no positive sense of direction. In other words, they were offensive because everything was badly done, and vaguely perceived to begin with. Russell’s work fuses words and actions to solid, concrete imagery, unlike the aesthetic imbecility of these films, all totally worthless achievements. The Devils assaults the mind with intelligence and honesty, but films like these assault the intelligence by their flagrant dishonesty and mindless sensibilities.

Russell’s film is offensive in a positive sense of the word because it presents a world of violence, cruelty, barbarism, and debauchery with straightforward, deeply intrinsic significance. It is not sacrilegious in the obvious sense for, as in the films of Luis Buñuel (Tristana, The Exterminating Angel, The Milky Way). Russell is not against religion or God as such, but in what man has made of God and religion, in the mockery and hypocrisy he has adopted towards them.

The world as an asylum, poisoned with its own fraudulence and lies, was often compellingly evoked in Peter Brook’s film of Peter Weiss’ play, Marat/Sade, and disturbingly rendered in Fellini Satyricon not only as asylum, but as hell on earth. Both these films had the potential of becoming offensive in the negative sense, but their makers possessed the strength of a consistent personal vision and a positive balance of morality that elevated them above the surface slime to frequently brilliant heights. But The Devils surpasses any and all such achievements, however superb.

Perhaps the closest relative to The Devils is Arthur Miller’s play, The Crucible, an interesting, yet curiously remote, lukewarm, superficial piece of melodrama. Its allegory of witchcraft equalling mass hysteria and individual paranoia is relatively mild compared with Whiting’s play. Miller’s work was written in reaction to the McCarthy Communism trials, and its theme of guilt by association is uncomfortably close to that of The Devils. But Whiting saw a much more diabolical, realistic, intense, and complex meaning than Miller’s shallow pretenses, and Russell has utilized Whiting’s work with most of its multi-facets intact.

Russell’s film is theatre of the cinema as well as cinema of the theatre. Like Miller, his theatricality is alive and flamboyant, bristling with violent human outburst, but never too theatrical to become ludicrous and inane, as Miller so often is.

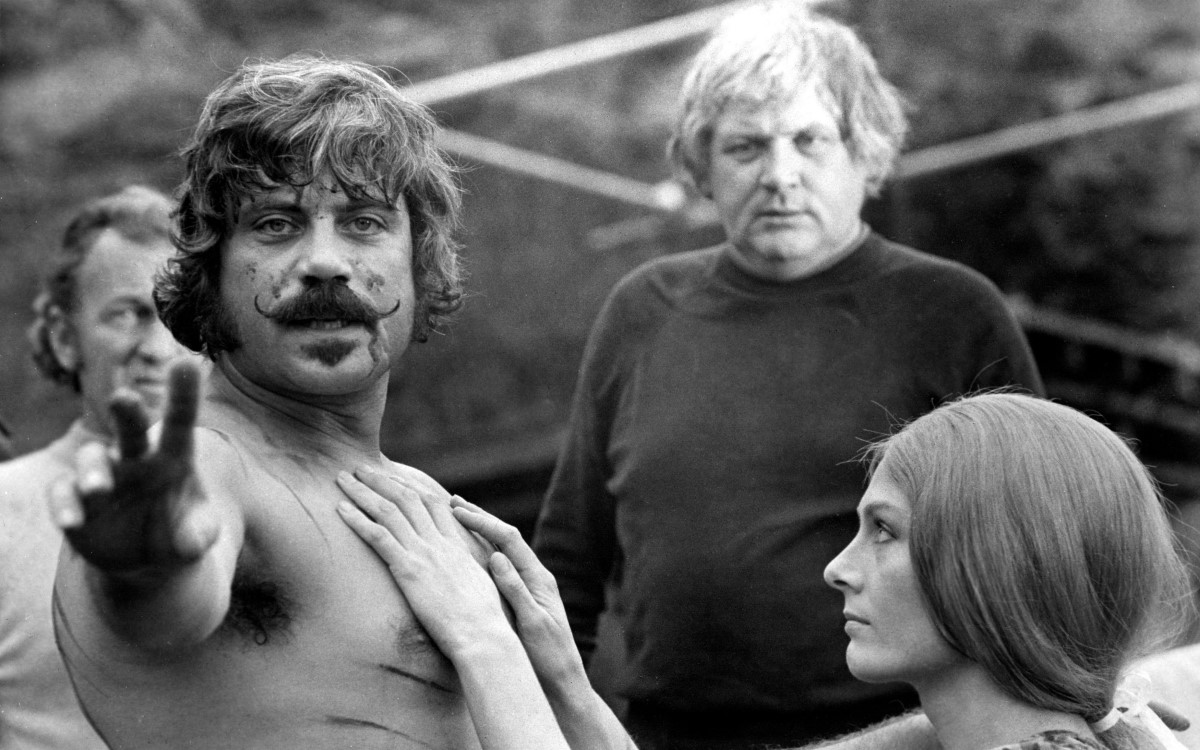

Oliver Reed’s performance as the man of God who realizes his own wrongs under the pressure of greater wrongs is one of the greatest ever on film. His purity of love for one innocent, lovely girl gives the film its few gently idyllic moments. In these scenes, Reed contrasts the man’s character so definitively that one views the man’s earlier sarcasm of God as mere self-deceit, one for which he is later gruesomely punished. His intensely powerful performance is never once too theatrical or consciously cinematic, but always in control, in close conjunction with the director’s vision as he always is.

As the hunchbacked Holy Sister whose inhibited lust, jealousy, and insanity leads the priest, by her accusations of witchcraft, to his death, Vanessa Redgrave gives a performance almost as superior as her Isadora Duncan portrayal. The deathlike calm that leads her to predictable madness has been evoked by Miss Redgrave with astounding inward perception and artistic conscience.

Never strong enough to become embarrassingly obvious, and never too underplayed to become non sequiturs, all the performers breathe a conviction of vitality and violence into each of their characters that surpasses most ensemble playing in any film.

Along with his photographer, David Watkin, Russell has visually captured a dark age of man that was truly pitch black with awesome, meticulous detail. One can almost taste the filth and disease, physically and mentally, of the era. Even the bleach-white bricks of the convent exude a coldness that hides a creeping horror, sickness, and death.

In his infamous book, The American Cinema, Andrew Sarris states, “In cinema, as in all art, only those who risk the ridiculous have a real shot at the sublime.” In essence, one might say that The Devils is ridiculous, but Russell has boldly taken that risk and has fashioned a film of unsurpassed power that reaches an abstract sublimity more affecting and disturbing than any film made recently or previously. As true as the events depicted in the film are, most people will reject them as ridiculous, just as easily as most people reject anything that is true. Truth does not always equal beauty, or vice versa.

Unfortunately, the film has been given the prestige treatment in advertising. A few words of caution are printed in fancy, ever-so-proper style, emphasizing the fact that the film is not for everybody. Large, bold-face type would be much more appropriate than this rather polite method, emphasizing the discretion that the individual must use before deciding to see the film.

The “X” rating is too mild for a film as totally honest as this one, and I don’t think that any rating could possibly fit a unique case such as this. The Devils is a film totally unto itself. Love it or despise it, it makes no difference. One is hardly likely to ever forget it, even if one badly wants to.

Cinefantastique, Spring 1972