AN OLD MAN’S DREAM OF GLORY

by David Denby

At the age of 70, Akira Kurosawa has made a stirring and beautiful film that is utterly unlike anything he’s done before. Spectacular yet severe, violent yet gravely formal, Kagemusha is marked by an overall nobility of style that extends to every gesture, stance, or movement. The nobility is familiar from past Kurosawa movies, yet the dark, discordant wit that accompanied the physical eloquence of such films as Rashomon and The Seven Samurai has been dropped, and the range of expressiveness is smaller. Kagemusha is relatively austere. I miss Kurosawa’s clowns, savages, and show-offs, his Shakespearean burlesque and pathos. The battle scenes aren’t as exciting as before, because Kurosawa has shifted his concern from a few brave men or a solitary figure to the fate of whole armies. But not even Griffith or Eisenstein has moved large masses of men with such appalling beauty. When the war drums boom, and hundreds of men in their black armor cascade down a hillside at dusk, the imagery is portentous and terrifying—an apocalypse charged with lightning.

In Kurosawa’s films, courage is an outward manifestation of inner virtue; moral and physical heroism are the same, indivisible. At first, Kagemusha, set in the late sixteenth century, seems to be about a non-hero. A condemned thief, about to be crucified, is rescued by a high authority and kept around as a potential double for a great man. The great man, Lord Shingen Takeda, the head of one of three powerful clans struggling to control Japan, wants the double around so his loyal generals can sustain his policies after he dies, keeping power out of the hands of his hothead son. A ruthless autocrat who is also a consummate leader, Shingen is known as “the mountain” for his steadfastness in battle, his prudence, his wisdom. Shot by a sniper during an assault on a rival’s castle, he is carried home, passing in sight of a lifelong goal, the capital city of Kyoto. Struggling to rise from his litter, he reaches fervently for the horizon; a flute sounds sharply, and he dies.

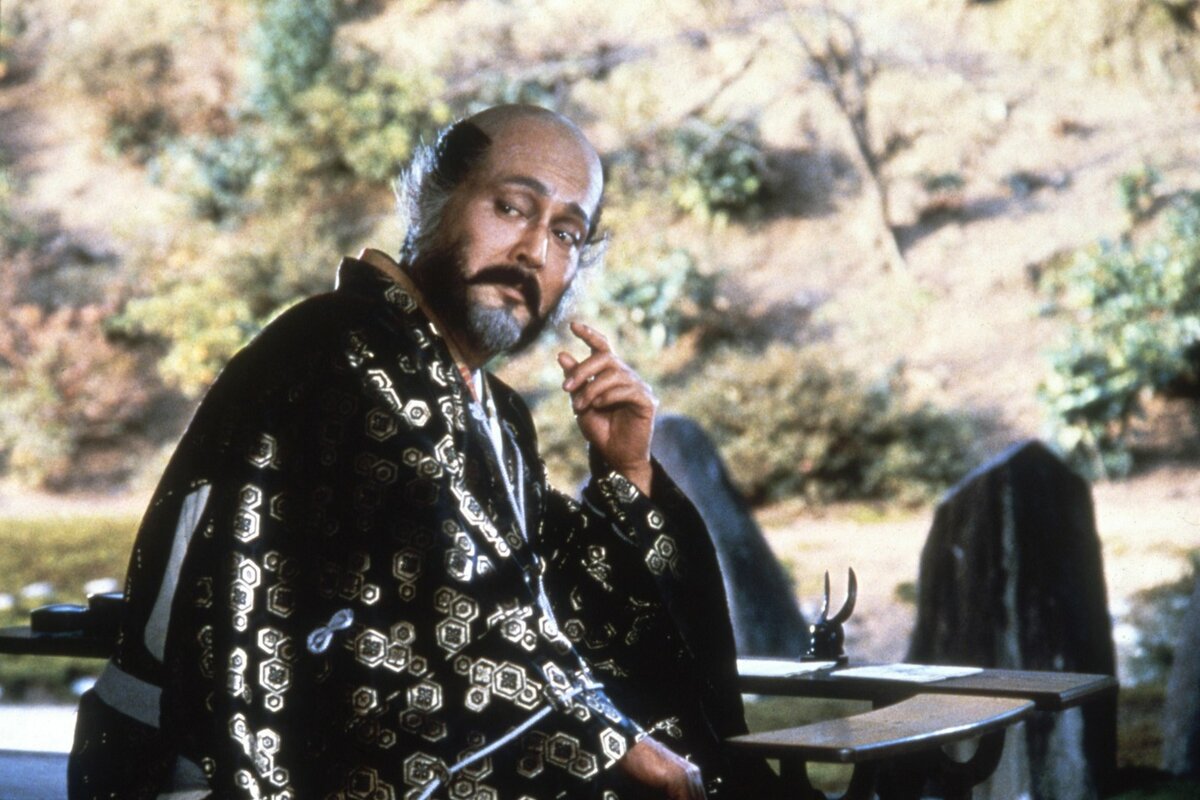

The double, known simply as Kagemusha (the shadow warrior), begs to be of service. A dead ringer for Shingen (Tatsuya Nakadai plays both roles), he is taught by Shingen’s younger brother how to sit, speak, and carry himself. Bearded, his head shaved across the top in sixteenth-century style, Tatsuya Nakadai has magnificently mobile eyes, brow, shoulders, trunk. He plays the double as an easygoing, loose-limbed man who struggles with comic fortitude to master the dead lord’s gravity and decisiveness. “Act natural, like him,” commands Shingen’s brother, and Nakadai’s face falls. How do you act “natural” when you have to act like someone else, and when “natural” means heroically strong and dignified? But the thief is ennobled by his service, and he learns his role well. Only the inner circle knows of the imposture.

He is aided in his deception by the uniquely moral character of Japanese formality. In this feudal society, the formal correctness of an act is so powerful a symbol that it finally doesn’t matter that Shingen has died. The audience for the imposter—the generals, the soldiers, even the rival clan leaders—all love Shingen’s greatness, love the ideal that he represents. They accept this double because his performance pays homage to the standards they all want to live up to. In the shadow’s greatest moment, he goes out to battle, perched on a ridge in full view of the enemy and his own troops. Galloping through the night, the legions of the enemy surround the Takeda clan, are temporarily repulsed, and then give up, daunted by the mystique of Shingen. Men fall on all sides of the shadow warrior, dying to protect an impostor, yet when he sits there, terrified yet unmoving, he is no longer a fraud. In the end, the non-hero become heroic.

There’s no ironic joke in Kagemusha, no clever, sour, conventional modern idea about image building or fakery. The double triumphs because everyone admires what he stands for. Kurosawa’s love of noble appearances is similar to John Ford’s in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which is also a “late” work by a pictorial master about people maintaining a legend that gives meaning to their lives. The fervency of belief in these two old warriors is intensely moving.

I would have enjoyed learning more about the shadow—what kind of man he was earlier in his life, how he felt about his impersonation—but Kagemusha is a study of acts, not motives or feelings. Like many fierce old men, Kurosawa may no longer care very much about feelings, doubts, “psychology.” Caught up in his mastery of physical movement and filmmaking craft, we may not much care ourselves. There are scenes of staggering beauty in this movie. The immense vistas with figures standing on a ridge in the foreground looking down at thousands of troops moving in the far distance may remind you of some of Griffith’s most spectacular moments. The massed horses, hooves pounding thunderously, sweep back and forth across the screen like tidal waves. Everything is erect, vibrant, heroically curt and decisive. The leaders of the rival clans, young warlords of passionate pride, meet in the middle of a field, standing up in the wind, with colored pennants billowing on all sides—it is like gods conferring in the clouds.

After three years, the double accidentally gives himself away. Useless now, he’s expelled from Shingen’s castle in a gray, driving rain. The reckless son takes over, disobeys Shingen’s dying commands, and immediately leads the clan’s 25,000-man army to destruction. The last battle—a massacre in which ranks of enemy gunners fire at men charging with lances—is recorded entirely in the eyes of the beholders. The suspense becomes unbearable. At last Kurosawa cuts to a battlefield laden with corpses and wounded horses kicking the air in agony. When it comes to images of destruction, he has no equal in the history of cinema. But what we’re likely to take away from Kagemusha is the nobility of a society bound in honor to a heroic ideal.

New York Magazine, October 27, 1980