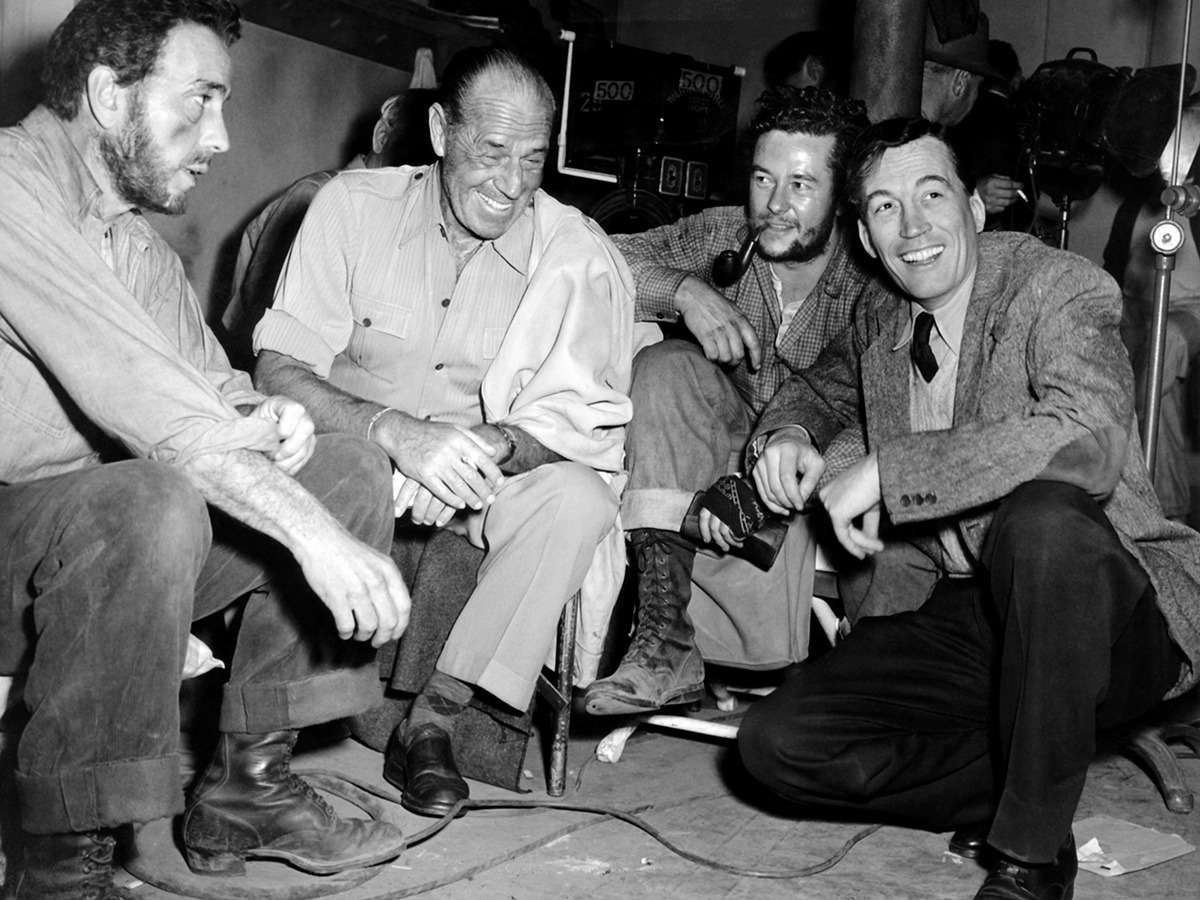

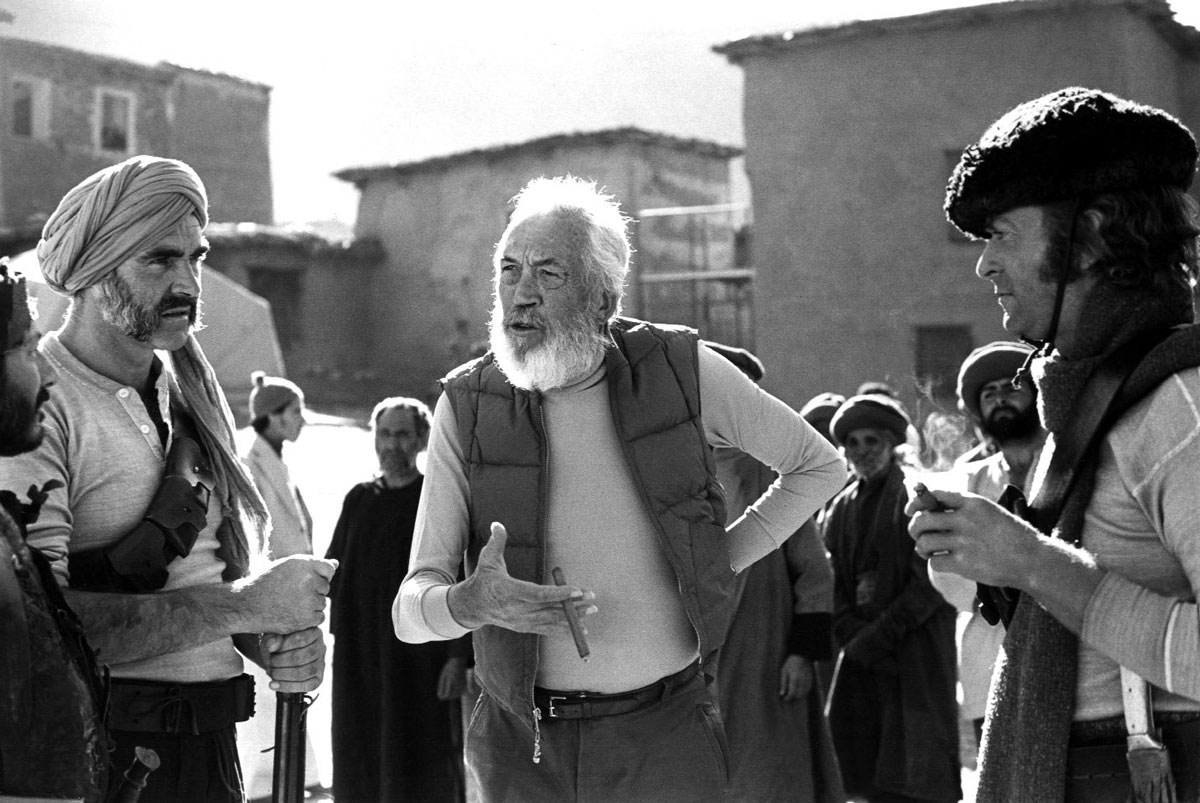

Of the directors whose work Agee most admired, John Huston was perhaps the one he was most personally drawn to. In the course of working on this article the two met for the first time. Subsequently they worked together on The African Queen.

by James Agee

The ant, as every sluggard knows, is a model citizen. His eye is fixed unwaveringly upon Security and Success, and he gets where he is going. The grasshopper, as every maiden ant delights in pointing out, is his reprehensible opposite number: a hedonistic jazz-baby, tangoing along primrose paths to a disreputable end. The late Walter Huston’s son John, one of the ranking grasshoppers of the Western Hemisphere, is living proof of what a lot of nonsense that can be. He has beaten the ants at their own game and then some, and he has managed that blindfolded, by accident, and largely just for the hell of it. John was well into his twenties before anyone could imagine he would ever amount to more than an awfully nice guy to get drunk with. He wandered into his vocation as a writer of movie scripts to prove to a girl he wanted to marry that he amounted to more than a likable bum. He stumbled into his still deeper vocation as a writer-director only when he got sick of seeing what the professional directors did to his scripts. But during the ten subsequent years he has won both Security aplenty (currently $3,000 a week with MGM and a partnership in Horizon Pictures with his friend Sam Spiegel) and Success aplenty (two Oscars, a One World Award and such lesser prizes as the Screen Directors’ Guild quarterly award which he received last week for his Asphalt Jungle).

Yet these are merely incidental attainments. The first movie he directed, The Maltese Falcon, is the best private-eye melodrama ever made. San Pietro, his microcosm of the meaning of war in terms of the fight for one hill town, is generally conceded to be the finest of war documentaries. Treasure of Sierra Madre, which he developed from B. Traven’s sardonic adventure-fable about the corrosive effect of gold on character, is the clearest proof in perhaps twenty years that first-rate work can come out of the big commercial studios.

Most of the really good popular art produced anywhere comes from Hollywood, and much of it bears Huston’s name. To put it conservatively, there is nobody under fifty at work in movies, here or abroad, who can excel Huston in talent, inventiveness, intransigence, achievement or promise. Yet it is a fair bet that neither money, nor acclaim, nor a sense of dedication to the greatest art medium of his century have much to do with Huston’s staying at his job: he stays at it because there is nothing else he enjoys so much. It is this tireless enjoyment that gives his work a unique vitality and makes every foot of film he works on unmistakably his.

Huston seems to have acquired this priceless quality many years ago at the time of what, in his opinion, was probably the most crucial incident in his life. When he was about twelve years old he was so delicate he was hardly expected to live. It was interminably dinned into him that he could never possibly be quite careful enough, and for even closer protection he was put into a sanitarium where every bite he ate and breath he drew could be professionally policed. As a result he became virtually paralyzed by timidity; “I haven’t the slightest doubt,” he still says, “that if things had gone on like that I’d have died inside a few more months.” His only weapon was a blind desperation of instinct, and by day not even that was any use. Nights, however, when everyone was asleep, he used to sneak out, strip, dive into a stream which sped across the grounds and ride it down quite a steep and stony waterfall, over and over and over. “The first few times,” he recalls, “it scared the living hell out of me, but I realized—instinctively anyhow—it was exactly fear I had to get over.” He kept at it until it was the one joy in his life. When they first caught him at this primordial autotherapy the goons were of course aghast; but on maturer thought they decided he might live after all.

The traits revealed in this incident are central and permanent in Huston’s character. Risk, not to say recklessness, are virtual reflexes in him. Action, and the most vivid possible use of the immediate present, were his personal salvation; they have remained lifelong habits. Because action also is the natural language of the screen and the instant present is its tense, Huston is a born popular artist. In his life, his dealings and his work as an artist he operates largely by instinct, unencumbered by much reflectiveness or abstract thinking, or any serious self-doubt. Incapable of yesing, apple-polishing or boot-licking, he instantly catches fire in resistance to authority.

Nobody in movies can beat Huston’s record for trying to get away with more than the traffic will bear. San Pietro was regarded with horror by some gentlemen of the upper brass as “an antiwar picture” and was cut from five reels to three. Treasure, which broke practically every box-office law in the game and won three Oscars, was made over the virtually dead bodies of the top men at Warners’ and was advertised as a Western. The Asphalt Jungle suggests that in some respects big-town crime operates remarkably like free enterprise. Huston seldom tries to “lick” the problem imposed by censorship, commercial queasiness or tradition; he has learned that nothing is so likely to settle an argument as to turn up with the accomplished fact, accomplished well, plus a bland lack of alternative film shots. And yet after innumerable large and small fights and a fair share of defeats he can still say of his movie career, “I’ve never had any trouble.” Probably the whitest magic that protects him is that he really means it.

Nonetheless his life began with trouble—decorated with the best that his Irish imagination, and his father’s, could add to it. He was born John Marcellus Huston on August 5, 1906, in Nevada, Missouri, a hamlet which his grandfather, a professional gambler, had by the most ambitious version of the family legend acquired in a poker game. John’s father, a retired actor, was in charge of power and light and was learning his job, while he earned, via a correspondence course. Before the postman had taught him how to handle such a delicate situation, a fire broke out in town, Walter overstrained the valves in his effort to satisfy the fire department, and the Hustons decided it would be prudent to leave what was left of Nevada before morning. They did not let their shirttails touch their rumps until they hit Weatherford, Texas, another of Grandfather’s jackpots. After a breather they moved on to St. Louis (without, however, repeating the scorched-earth policy), and Walter settled down to engineering in dead earnest until a solid man clapped him on the shoulder and told him that with enough stick-to-itiveness he might well become a top-notch engineer, a regular crackerjack. Horrified, Walter instantly returned to the stage. A few years later he and his wife were divorced. From there on out the child’s life lacked the stability of those early years.

John divided his time between his father and mother. With his father, who was still some years short of eminence or even solvency, he shared that bleakly glamorous continuum of three-a-days, scabrous fleabags and the tindery, ambling day coaches between, which used to be so much of the essence of the American theater. John’s mother was a newspaperwoman with a mania for travel and horses (she was later to marry a vice-president of the Northern Pacific), and she and her son once pooled their last ten dollars on a 100-to-1 shot—which came in. Now and then she stuck the boy in one school or another, but mostly they traveled—well off the beaten paths.

After his defeat of death by sliding down the waterfall, there was no holding John. In his teens he became amateur lightweight boxing champion of California. A high-school marriage lasted only briefly. He won twenty-three out of twenty-five fights, many in the professional ring, but he abandoned this promise of a career to join another of his mother’s eccentric grand tours. He spent two years in the Mexican cavalry, emerging at twenty-one as a lieutenant. In Mexico he wrote a book, a puppet play about Frankie and Johnny. Receiving, to his astonishment, a $500 advance from a publisher, he promptly entrained for the crap tables of Saratoga where, in one evening, he ran it up to $11,000, which he soon spent or gambled away.

After that Huston took quite a friendly interest in writing. He wrote a short story which his father showed to his friend Ring Lardner, who showed it to his friend H. L. Mencken, who ran it in the Mercury. He wrote several other stories about horses and boxers before the vein ran out. It was through these stories, with his father’s help that he got his first job as a movie writer. He scripted A House Divided, starring his father, for William Wyler. But movies, at this extravagant stage of Huston’s career, were just an incident. At other stages he worked for the New York Graphic (“I was the world’s lousiest reporter”), broke ribs riding steeplechase, studied painting in Paris, knocked around with international Bohemians in London and went on the bum in that city when his money ran out and he was too proud to wire his father. At length he beat his way back to New York where, for a time, he tried editing the Midweek Pictorial. He was playing Abraham Lincoln in a Chicago WPA production when he met an Irish girl named Leslie Black and within fifteen minutes after their meeting asked her to marry him. When she hesitated he hotfooted it to Hollywood and settled down to earn a solid living as fast as possible. Marrying Leslie was probably the best thing that ever happened to him, in the opinion of Huston’s wise friend and studio protector during the years at Warner Brothers, the producer Henry Blanke. Blanke remembers him vividly during the bachelor interlude: “Just a drunken boy; hopelessly immature. You’d see him at every party, wearing bangs, with a monkey on his shoulder. Charming. Very talented but without an ounce of discipline in his make-up.” Leslie Huston, Blanke is convinced, set her husband the standards and incentives which brought his abilities into focus. They were divorced in 1945, but in relation to his work he has never lost the stability she helped him gain.

At forty-four Huston still has a monkey and a chimpanzee as well, but he doesn’t escort them to parties. His gray-sleeted hair still treats his scalp like Liberty Hall and occasionally slithers into bangs, but they can no longer be mistaken for a Bohemian compensation. He roughly suggests a jerked-venison version of his father, or a highly intelligent cowboy. A little over six feet tall, quite lean, he carries himself in a perpetual gangling-graceful slouch. The forehead is monkeyishly puckered, the ears look as clipped as a show dog’s; the eyes, too, are curiously animal, an opaque red-brown. The nose was broken in the prize ring. The mouth is large, mobile and gap-toothed. The voice which comes out of this leatheriness is surprisingly rich, gentle and cultivated. The vocabulary ranges with the careless ease of a mountain goat between words of eight syllables and of four letters.

Some friends believe he is essentially a deep introvert using every outside means available as a form of flight from self-recognition—in other words, he is forever sliding down the waterfall and instinctively fears to stop. The same friends suspect his work is all that keeps him from flying apart. He is wonderful company, almost anytime, for those who can stand the pace. Loving completely unrestrained and fantastic play, he is particularly happy with animals, roughhousers and children; a friend who owns three of the latter describes him as “a blend of Santa Claus and the Pied Piper.” His friendships range from high in the Social Register to low in the animal kingdom, but pretty certainly the friend he liked best in the world was his father, and that was thoroughly reciprocated. It was a rare and heart-warming thing, in this Freud-ridden era, to see a father and son so irrepressibly pleased with each other’s company and skill.

He has an indestructible kind of youthfulness, enjoys his enthusiasms with all his might and has the prompt appetite for new knowledge of a man whose intelligence has not been cloyed by much formal education. He regrets that nowadays he can read only two or three books a week. His favorite writers are Joyce, his friend Hemingway (perhaps his closest literary equivalent) and, above all, O’Neill; it was one of the deepest disappointments of his career when movie commitments prevented his staging the new O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh. His other enjoyments take many forms. He still paints occasionally. He is a very good shot and a superlative horseman; he has some very promising runners of his own. He likes money for the fun it can bring him, is extremely generous with it and particularly loves to gamble. He generally does well at the races and siphons it off at the crap tables. He is a hard drinker (Scotch) but no lush, and a heavy smoker. Often as not he forgets to eat. He has a reputation for being attractive to women, and rough on them. His fourth wife is the dancer, Ricky Soma; their son Walter was born last spring. He makes most of his important decisions on impulse; it was thus he adopted his son Pablo in Mexico. The way he and his third wife, Evelyn Keyes, got married is a good example of Huston in action. He suggested they marry one evening in Romanoff’s a week after they met, borrowed a pocketful of money from the prince, tore out to his house to pick up a wedding ring a guest had mislaid in the swimming pool and chartered Paul Mantz to fly them to Las Vegas where they were married that night.

Huston’s courage verges on the absolute, or on simple obliviousness to danger. In Italy during the shooting of San Pietro, his simian curiosity about literally everything made him the beau ideal of the contrivers of booby traps; time and again he was spared an arm, leg or skull only by the grace of God and the horrified vigilance of his friend Lieutenant Jules Buck. He sauntered through mine fields where plain man feared to tread. He is quick to get mad and as quick to get over it. Once in Italy he sprinted up five flights of headquarters stairs in order to sock a frustrating superior officer; arriving at the top he was so winded he could hardly stand. Time enough to catch his breath was time enough to cool off; he just wobbled down-stairs again.

Huston is swiftly stirred by anything which appeals to his sense of justice, magnanimity or courage: he was among the first men to stand up for Lew Ayres as a conscientious objector, he flew to the Washington hearings on Hollywood (which he refers to as “an obscenity”) and sponsored Henry Wallace (though he voted for Truman) in the 1948 campaign. Some people think of him, accordingly, as a fellow traveler. Actually he is a political man chiefly in an emotional sense: “I’m against anybody” he says, “who tries to tell anybody else what to do.” The mere sight or thought of a cop can get him sore. He is in short rather less of a Communist than the most ultramontane Republican, for like perhaps five out of seven good artists who ever lived he is—to lapse into technical jargon—a natural-born antiauthoritarian individualistic libertarian anarchist, without portfolio.

A very good screen writer, Huston is an even better director. He has a feeling about telling a story on a screen which sets him apart from most other movie artists and from all non-movie waiters and artists. “On paper,” he says, “all you can do is say something happened, and if you say it well enough the reader believes you. In pictures, if you do it right, the thing happens, right there on the screen.”

This means more than it may seem to. Most movies are like predigested food because they are mere reenactments of something that happened (if ever) back in the scripting stage. At the time of shooting the sense of the present is not strong, and such creative energy as may be on hand is used to give the event finish, in every sense of the word, rather than beginning and life. Huston’s work has a unique tension and vitality because the maximum of all contributing creative energies converge at the one moment that counts most in a movie—the continuing moment of committing the story to film. At his best he makes the story tell itself, makes it seem to happen for the first and last time at the moment of recording. It is almost magically hard to get this to happen. In the Treasure scene in which the bandits kill Bogart, Huston wanted it to be quiet and mock-casual up to its final burst of violence. He told two of his three killers—one a professional actor, the other two professional criminals—only to stay quiet and close to the ground, and always to move when Bogart moved, to keep him surrounded. Then he had everyone play it through, over and over, until they should get the feel of it. At length one of them did a quick scuttling slide down a bank, on his bottom and his busy little hands and feet. A motion as innocent as a child’s and as frightening as a centipede’s, it makes clear for the first time in the scene that death is absolutely inescapable, and very near. “When he did that slide,” Huston says, “I knew they had the feel of it.” He shot it accordingly.

Paradoxically in this hyperactive artist of action, the living, breathing texture of his best work is the result of a working method which relies on the utmost possible passiveness. Most serious-minded directors direct too much: “Now on this word,” Huston has heard one tell an actor, “I want your voice to break.” Actors accustomed to that land of “help” are often uneasy when they start work with Huston. “Shall I sit down here?” one asked, interrupting a rehearsal. “I dunno,” Huston replied. “You tired?” When Claire Trevor, starting work in Key Largo, asked for a few pointers, he told her, “You’re the kind of drunken dame whose elbows are always a little too big, your voice is a little too loud, you’re a little too polite. You’re very sad, very resigned. Like this,” he said, for short, and leaned against the bar with a peculiarly heavy, gentle disconsolateness. It was the leaning she caught onto (though she also used everything he said); without further instruction of any kind, she took an Oscar for her performance. His only advice to his father was a whispered, “Dad, that was a little too much like Walter Huston.” Often he works with actors as if he were gentling animals; and although Bogart says without total injustice that “as an actor he stinks,” he has more than enough mimetic ability to get his ideas across. Sometimes he discards instruction altogether: to get a desired expression from Lauren Bacall, he simply twisted her arm.

Even on disastrously thin ice Huston has the peculiar kind of well-earned luck which Heaven reserves exclusively for the intuitive and the intrepid. One of the most important roles in Treasure is that of the bandit leader, a primordial criminal psychopath about whom the most fascinating and terrifying thing is his unpredictability. It is impossible to know what he will do next because it is impossible to be sure what strange piece of glare-ice in his nature will cause a sudden skid. Too late for a change, it turned out that the man who played this role, though visually ideal for it, couldn’t act for shucks. Worried as he was, Huston had a hunch it would turn out all right. It worked because this inadequate actor was trying so hard, was so unsure of what he was doing and was so painfully confused and angered by Huston’s cryptic passivity. These several kinds of strain and uncertainty, sprung against the context of the story, made a living image of the almost unactable, real thing; and that had been Huston’s hunch.

In placing and moving his characters within a shot Huston is nearly always concerned above all else to be simple and spontaneous rather than merely “dramatic” or visually effective. Just as he feels that the story belongs to the characters, he feels that the actors should as fully as possible belong to themselves. It is only because the actors are so free that their several individualities, converging in a scene, can so often knock the kinds of sparks off each other which cannot be asked for or invented or foreseen. All that can be foreseen is that this can happen only under favorable circumstances; Huston is a master at creating such circumstances.

Each of Huston’s pictures has a visual tone and style of its own, dictated to his camera by the story’s essential content and spirit. In Treasure the camera is generally static and at a middle distance from the action (as Huston says, “It’s impersonal, it just looks on and lets them stew in their own juice”); the composition is—superficially—informal, the light cruel and clean, like noon sun on quartz and bone. Most of the action in Key Largo takes place inside a small Florida hotel. The problems are to convey heat, suspense, encloscdness, the illusion of some eighteen hours of continuous action in two hours’ playing time, with only one time lapse. The lighting is stickily fungoid. The camera is sneakily “personal”; working close and in almost continuous motion, it enlarges the ambiguous suspensefulness of almost every human move. In Strangers the main pressures are inside a home and beneath it, where conspirators dig a tunnel. Here Huston’s chief keys are lighting contrasts. Underground the players move in and out of shadow like trout; upstairs the light is mainly the luminous pallor of marble without sunlight: a cemetery, a bank interior, a great outdoor staircase.

Much that is best in Huston’s work comes of his sense of what is natural to the eye and his delicate, simple feeling for space relationships: his camera huddles close to those who huddle to talk, leans back a proportionate distance, relaxing, if they talk casually. He loathes camera rhetoric and the shot-for-shot’s-sake; but because he takes each moment catch-as-catch-can and is so deeply absorbed in doing the best possible thing with it he has made any number of unforgettable shots. He can make an unexpected close-up reverberate like a gong. The first shot of Edward G. Robinson in Key Largo, mouthing a cigar and sweltering naked in a tub of cold water (“I wanted to get a look at the animal with its shell off”) is one of the most powerful and efficient “first entrances” of a character on record. Other great shots come through the kind of candor which causes some people to stare when others look away: the stripped, raw-sound scenes of psychiatric interviews in Let There Be Light. Others come through simple discretion in relating word and image. In San Pietro, as the camera starts moving along a line of children and babies, the commentator (Huston) remarks that in a few years they’ll have forgotten there ever was a war; then he shuts up. As the camera continues in silence along the terrible frieze of shock and starvation, one realizes the remark was not the inane optimism it seemed: they, forgetting, are fodder for the next war.

Sometimes the shot is just a spark—a brief glint of extra imagination and perception. During the robbery sequence in Asphalt Jungle there is a quick glimpse of the downtown midnight street at the moment when people have just begun to hear the burglar alarms. Unsure, still, where the trouble is, the people merely hesitate a trifle in their ways of walking, and it is like the first stirrings of metal filings before the magnet beneath the paper pulls them into pattern. Very often the fine shot comes because Huston, working to please himself without fear of his audience, sharply condenses his storytelling. Early in Strangers a student is machine-gunned on the steps of Havana s university. A scene follows which is breath-taking in its surprise and beauty, but storytelling, not beauty, brings it: what seems to be hundreds of young men and women, all in summery whites, throw themselves flat on the marble stairs in a wavelike motion as graceful as the sudden close swooping of so many doves. The shot is already off the screen before one can realize its full meaning. By their trained, quiet unison in falling, these students are used to this. They expect it any average morning. And that suffices, with great efficiency, to suggest the Cuban tyranny.

Within the prevailing style of a picture, Huston works many and extreme changes and conflicts between the “active” camera, which takes its moment of the story by the scruff of the neck and “tells” it, and the “passive” camera, whose business is transparency, to receive a moment of action purely and record it. But whether active or passive, each shot contains no more than is absolutely necessary to make its point and is cut off sharp at that instant. The shots are cantilevered, sprung together in electric arcs, rather than buttered together. A given scene is apt to be composed of highly unconventional alternations of rhythm and patterns of exchange between long and medium and close shots and the standing, swinging and dollying camera. The rhythm and contour are very powerful but very irregular, like the rhythm of good prose rather than of good verse; and it is this rangy, leaping, thrusting kind of nervous vitality which binds the whole picture together. Within this vitality he can bring about moments as thoroughly revealing as those in great writing. As an average sample of that, Treasure’s intruder is killed by bandits; the three prospectors come to identify the man they themselves were on the verge of shooting. Bogart, the would-be tough guy, cocks one foot up on a rock and tries to look at the corpse as casually as if it were fresh-killed game. Tim Holt, the essentially decent young man, comes past behind him and, innocent and unaware of it, clasps his hands as he looks down, in the respectful manner of a boy who used to go to church. Walter Huston, the experienced old man, steps quietly behind both, leans to the dead man as professionally as a doctor to a patient and gently rifles him for papers. By such simplicity Huston can draw the eye so deep into the screen that time and again he can make important points in medium shots, by motions as small as the twitching of an eyelid, for which most directors would require a close-up or even a line of dialogue.

Most movies are made in the evident assumption that the audience is passive and wants to remain passive; every effort is made to do all the work—the seeing, the explaining, the understanding, even the feeling. Huston is one of the few movie artists who, without thinking twice about it, honors his audience. His pictures are not acts of seduction or of benign enslavement but of liberation, and they require, of anyone who enjoys them, the responsibilities of liberty. They continually open the eye and require it to work vigorously; and through the eye they awaken curiosity and intelligence. That, by any virile standard, is essential to good entertainment. It is unquestionably essential to good art.

The most inventive director of his generation, Huston has done more to extend, invigorate and purify the essential idiom of American movies, the truly visual telling of stories, than anyone since the prime of D. W. Griffith. To date, however, his work as a whole is not on the level with the finest and most deeply imaginative work that has been done in movies—the work of Chaplin, Dovzhenko, Eisenstein, Griffith, the late Jean Vigo. For an artist of such conscience and caliber, his range is surprisingly narrow, both in subject matter and technique. In general he is leery of emotion—of the “feminine” aspects of art and if he explored it with more assurance, with his taste and equipment, he might show himself to be a much more sensitive artist. With only one early exception, his movies have centered on men under pressure, have usually involved violence and have occasionally verged on a kind of romanticism about danger. Though he uses sound and dialogue more intelligently than most directors, he has not shown much interest in exploring the tremendous possibilities of the former or in solving the crippling problems of the latter. While his cutting is astute, terse, thoroughly appropriate to his kind of work, yet compared with that of Eisenstein, who regarded cutting as the essence of the art of movies, it seems distinctly unadventurous. In his studio pictures, Huston is apt to be tired and bored by the time the stages of ultrarefinement in cutting are reached, so that some of his scenes have been given perfection, others somewhat impaired, by film editors other than Huston. This is consistent with much that is free and improvisatory in his work and in his nature, but it is a startling irresponsibility in so good an artist.

During his past few pictures Huston does appear to have become more of a “camera” man, and not all of this has been to the good. The camera sometimes imposes on the story; the lighting sometimes becomes elaborately studioish or even verges on the arty; the screen at times becomes rigid, overstylized. This has been happening, moreover, at a time when another of Huston’s liabilities has been growing: thanks to what Henry Blanke calls his “amazing capacity for belief,” he can fall for, and lose himself in, relatively mediocre material. Sometimes—as in Asphalt Jungle—he makes a silk purse out of sow’s ear, but sometimes—as in parts of Strangers and Key Largo—the result is neither silk nor sow.

Conceivably Huston lacks that deepest kind of creative impulse and that intense self-critical skepticism without which the stature of a great artist is rarely achieved. A brilliant adapter, he has yet to do a Huston “original,” barring the war documentaries. He is probably too much at the mercy of his immediate surroundings. When the surroundings are right for him there is no need to talk about mercy: during the war and just after he was as hard as a rock and made his three finest pictures in a row. Since then the pictures, for all their excellence, are, like the surroundings, relatively softened and blurred. Unfortunately no man in Hollywood can be sufficiently his own master or move in a direct line to personally selected goals. After Treasure, Huston was unable to proceed to Moby Dick as he wanted to; he still is awaiting the opportunity to make Dreiser’s Jennie Gerhardt and Dostoevski’s The Idiot although he is at last shooting Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, which he has wanted to make for years. “This has got to be a masterpiece,” he recently told friends, “or it’s nothing.”

There is no reason to expect less of it than his finest picture yet, for the better his starting material, the better he functions as an artist: he is one of the very few men in the world of movies who has shown himself to be worthy of the best. He has, in abundance, many of the human qualities which most men of talent lack. He is magnanimous, disinterested and fearless. Whatever his job, he always makes a noble and rewarding fight of it. If it should occur to him to fight for his life—his life as the consistently great artist he evidently might become— he would stand a much better chance of winning than most people. For besides having talent and fighting ability, he has nothing to lose but his hide, and he has never set a very high value on that.

Life, September 18, 1950