by Dilys Powell

Full title to begin with: Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. With a name like that it obviously isn’t a solemn film, though it deals with a solemn subject. But its origins are not, apparently, in comedy.

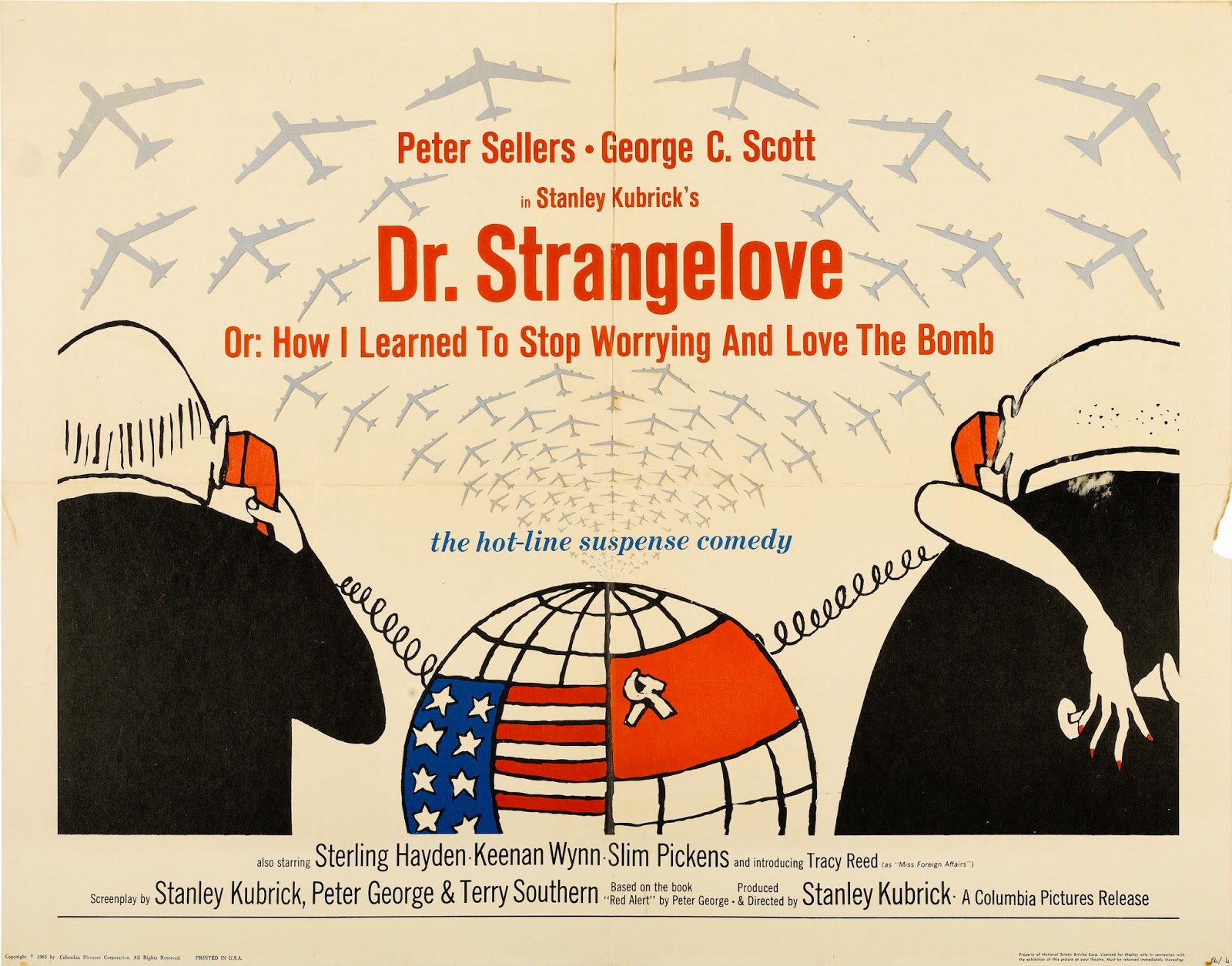

Dr Strangelove is based, one is told, on a straightforward thriller about the chance of starting a nuclear war by mistake. The director, Stanley Kubrick, working with the American novelist Terry Southern and Peter George, author of the thriller, has taken the story and turned it into an appalling, and I mean appalling, joke; he calls it a nightmare comedy.

I suppose the description is as good as any. I have been searching for a parallel to the film. Nothing really like it in the cinema; political jokes, yes, but not doomsday jokes, and the possibility of blowing the world up offers a theme for which black comedy is a phrase much too blond. Turning to literature, I think vaguely of Swift and his Modest Proposal for disposing of inconveniently starving Irish children by serving them up for dinner; the straight face which is so telling in Kubrick’s film is there in Swift, and so is the deathly idea. But then you don’t get a belly-laugh from reading Swift.

Swift and slapstick: perhaps that would be nearer. But this isn’t exactly slapstick. It is a succession of minor mishaps in the Harold Lloyd manner: mis-arrangements, miscalculations, each in itself a major absurdity because of its consequences. A plan devised to guard against human error succeeds only in guarding against the correction of error, in preventing anybody, and that goes for the President of the United States, from countermanding the order to bomb. Everybody, in this safety system, is cut off from everybody else: cut off by design; by the conviction that the other fellow is a Commie (the Pentagon general’s word, not mine) who has managed to dress up as an American; and by such incidentals as shortage of change for making a trunk call. You laugh at the mixture of trivial accident and misapplied ingenuity, you laugh at the disproportion between causes and effects, and in a shuddering way you laugh all the more (tragedy often contains a shame-faced element of comedy) because the danger which threatens is universal, horrible and real.

The double-face of the story – serious events broken up into farcical incidents – is expressed in double-face acting of a high order. There is Sterling Hayden as the general in command of the strategic air base who at the start of the film sets the ball, or rather the Bomb, rolling: a portrait of a psychotic fanaticism twisted now and then into the ridiculous by an emphatic braking of pace or a pleased inflection of the voice (and strengthened, I should add, in its ferocity by the use of carefully angled close-ups). There is George C. Scott as the general called on, at the meeting in the Pentagon War Room, to reply to the incredulous expostulations of the President: gleefully glib in his account of the provisions which prevent the recall of the bombers, exploding into maniac suspicion at the sight of the Russian Ambassador – Mr Scott moves in a blaze of nihilistic idiocy between satire and burlesque.

And there is Peter Sellers; and here one has to drop double-face and, using the phrase in strict accuracy, substitute treble-face. Mr Sellers plays three roles. He plays the President struggling to convey the news to Russia over the hot telephone (the writing of this monologue is a little masterpiece of comic euphemism). He plays an R.A.F. officer at the American base. And he plays Dr Strangelove, a scientist from Germany who has changed his name but not his nature.

The last portrait is the least successful of the three because the most extravagant – it is, in any case, involved in the final War Room scene which, deprived of the cross-cutting to the bomber’s desperate flight – cross-cutting which gives earlier passages a painful comic tension -drops into a slightly slack, speculative mood. Least successful — but still, with its uncontrollable reversions to Nazi type, successful enough, and I fancy that if anybody else had achieved its diabolic glitter one’s reactions would be all-admiring.

The difficulty is that Mr Sellers is in competition with Mr Sellers, and the standard can’t be set higher. The Sellers President, a decent rational being in a lunatic situation, makes delicate play with the irony of embarrassment. The Sellers R.A.F. type is another reasonable, reliable man beset by the mad and the mulish, but here the portrait, enriched by national traits and class mannerisms – the sloping walk, the voice from the back of the nose, the amiable off-hand approach – adds a particular pleasure which makes the performance my favourite: the pleasure of recognition, I know that Group Captain, and sitting at my typewriter I laugh when I think of him.

The President and the Group Captain are played without caricature and in the context they are all the funnier for it. But farce is essential to the film. Fantastic farce governs the climax; and if you are against that, think of the alternative. For me at any rate farce makes the theme of Dr Strangelove not only more bearable, but also more believable.

After all it is difficult to accept Doomsday unless as a monstrous joke.

The Sunday Times, February 1964

Republished in Dilys Powell, The Golden Screen: Fifty Years at the Films