by Nick Clooney

U.S. Air Force Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper goes mad and orders his bombers to attack Russia. He seals off his base, locks down the code, and prevents everyone from contacting the planes, including President Merkin Muffley, who frantically calls in his top advisers, womanizing General “Buck” Turgidson and a demented German scientist, Dr. Strangelove.

Various plots to stop the bombers fail. The Russians are let in on the secret, but remain suspicious. General Ripper, his headquarters invaded, kills himself rather than order his attack to stop. All the bombers are shot down but one, piloted by the crafty Major “King” Kong. When the atom bomb sticks in the bay, Kong personally releases it and rides it to the world’s doom.

Note: One of Kubrick’s original scripts had the nuclear confrontation ending with a gigantic custard-pie throwing contest among the military, the diplomats, and the politicians.

Hurry, hurry, hurry, come one, come all, come get your wars! Wars of all shapes and sizes: Great Wars, Banana Wars, Gunboat Wars, World Wars, Great Patriotic Wars, Wars of Liberation, Ethnic Cleansing Wars, Wars on Terrorism, wars for every taste and every occasion!

The twentieth century was a war lover’s dream. All those eager little boys who painstakingly set up their ranks and files of lead soldiers in precise formation, then gleefully knocked them helter-skelter had a century to die for.

But, by the century’s sixth decade, a surfeit of war was becoming something of a problem. It started to be apparent that too many were dying, which was giving war a bad name. Instead of professional—or at least volunteer—armies slugging it out on isolated battlefields, trained soldiers dying at a rate acceptable to everyone except those who died, the twentieth century produced wars that involved entire populations. No longer was war just a grown-up version of all those six-year-old generals sending phalanxes of metal warriors to their make-believe doom, flags flying and bugles blaring.

Men were getting too good at the destruction trade. Whole towns, then cities, were leveled, the line of demarcation between combatant and noncombatant demolished with the bricks and mortar. So many were dying that too few were left to stand on the sidelines and cheer the heroes. There were no sidelines.

Finally, after all the machine guns, the Big Berthas, the tanks, the superfortresses, the blockbusters, the V-2, men found the ultimate weapon, unleashing the very power of nature, splitting the nuclei of uranium 235 and sending fireballs and shockwaves and radioactive fallout in such immense quantities that even the most warlike were given pause.

For once, Hollywood was stumped. They didn’t know what to do with the atomic age, an accurate reflection of the bewilderment and anxiety felt by the rest of us. For the brief four years of the American monopoly on the nuclear weapon, major movies made virtually no reference to the revolution that had occurred. If films dealt with war, it was a retrospective on the cataclysm the world had just narrowly survived. Exactly as the Hollywood of the 1930s ignored or made fun of the Depression, Hollywood of 1945-1950 ignored the New Atomic Age.

In 1949, America learned that it no longer had the nuclear secret to itself. The Soviet Union exploded an atomic bomb and they clearly had the delivery system to make it viable.

And so, the most famous and dangerous standoff in history began. It would consume billions of dollars, draining the treasuries of great nations. It would affect, in ways large and small, every living creature on the globe. In a classic irony, it would also prevent what most of those alive on the planet in 1945 thought was inevitable: a Third World War.

The two great antagonists would nibble at the periphery, but neither dared challenge the other directly. Thousands would die, but not millions. In the coin of the Cold War, the rate of exchange was favorable.

We developed phrases for it, eventually. The euphonious “Equilibrium of Terror.” The more directly to the point “Mutually Assured Destruction.” “M-A-D,” indeed.

The 1950s found mainstream Hollywood slow to take on the Cold War, at least directly. Not until the end of the decade did a big-budget film deal with the possibility of the end of life on earth because of the actions of irresponsible governments,- 1959’s excellent On the Beach, the Nevil Shute novel, directed by Stanley Kramer.

The 1960s would be different.

Antiwar themes began to appear timidly in films. Writers who had held their peace for fear of tipping the delicate international balance were silent no longer, and their voices were now being heard in the central spaces of society; the living rooms.

The Cuban missile crisis raised the temperature to fever pitch in 1962. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 unleashed forces of doubt and dissent that would boil, then boil over, for a decade. Thomas Jefferson once observed “Some will always prefer the tranquility of tyranny to the boisterous sea of liberty.” America’s view of liberty was boisterous enough in the 1960s to shake the foundations of most institutions and assumptions.

In 1964, in a coincidence of purposes, three remarkable filmmakers released antiwar movies within months of one another. John Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May; Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe, and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

The first presented the possibility of a coup by the American military, grown powerful and arrogant because of its prominence in the Cold War—and holding the nuclear card as trump. The second offered the premise that both the United States and the U.S.S.R. put too much trust in technology to keep nations from nuclear disaster, by presenting a chilling story of technology gone awry, with the U.S. sending a fleet of bombers bearing atom bombs to destroy Russia.

Both films, by doomsday standards, had semihappy endings. In Seven Days, the coup is averted. In Fail Safe, only two great cities—Moscow and New York—are annihilated along with their populations. The rest of the world is presumably saved.

Stanley Kubrick was having none of that. In the darkest comedy of its age, the closing of Dr. Strangelove finds nuclear blast after nuclear blast going off all over the world, obliterating civilization while that most civilized of singers, Dame Vera Lynn, sings the brave “chin-up” song of World War II, “We’ll Meet Again.”

It should be no surprise that the casts of those three movies are virtually all male.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was the most successful antiwar movie of the nuclear age up to that time. Though it bore no resemblance to 1925’s The Big Parade, its influence was the same: it opened the gates for antiwar themes in the movies, first a trickle, then a flood in the wind-down of the Vietnam War.

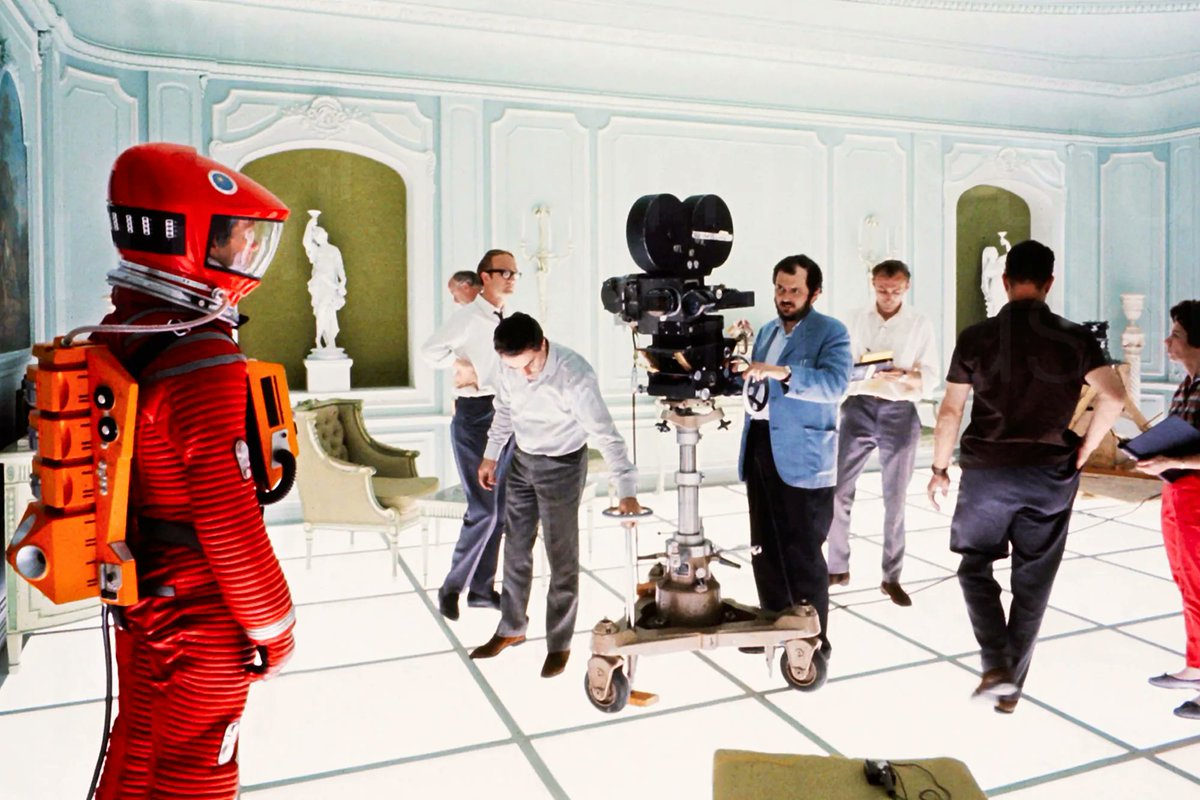

This was Stanley Kubrick’s project from the beginning. He was not only the director,- he was also the producer and the coscreenwriter.

Mr. Kubrick was born in the Bronx and by the time he was seventeen, in 1945, he was a staff photographer for one of the leading magazines of the day, Look. Five years later, he decided to become a filmmaker, quitting his job and putting his energies into documentaries. Within a few years he had borrowed from everyone he knew in order to make a feature film, Fear and Desire. Kubrick did everything except the acting. He wrote, produced, directed, loaded film, shot it, then edited it. He was encouraged enough to do another film in exactly the same manner, and then, in 1954, to form a production company, get a bigger budget, hire a professional cast that included Sterling Hayden, and make the crime drama The Killing. This is the vehicle that got the attention of critics.

Stanley Kubrick’s next film would tell us what he was all about. His work had been seen by Kirk Douglas, who was about to make a major film based on a 1934 novel by Humphrey Cobb, Paths of Glory. Mr. Kubrick was one of three writers who would adapt the novel and Mr. Kubrick would direct.

By every measure except one, Paths of Glory was a stunning debut. This 1957 film was the most fully realized antiwar film of the decade, even though the war being excoriated was World War I and the military establishment condemned was that of France. The acting, the production values, the directing techniques ranked with the best Hollywood had seen, and the undiluted message was so powerful that the film was banned in France. In fact, it was also banned from many U.S. military bases.

The film’s condemnation of the officer corps, the exposing of the heartless and brainless system under which hundreds of thousands had died, was powerful medicine and not many were prepared to take it. The movie was a financial failure.

Kubrick would not make that mistake seven years later. Though Dr. Strangelove was every bit as brutal in its renunciation of the military as Paths of Glory, it was a comedy. The audience was free to take as much—or as little—from it as they chose.

Some left the theater laughing, quoting one-liners. Others left deeply depressed, wondering if they had seen a fragment of the future. Whatever their motives in going or their reactions after the fact, they made the cash registers ring. Stanley Kubrick, in a film over which he had complete control, had a hit. ’

The critical community, as it usually is, was divided. Saturday Review called it “a true satire with the whole human race as the ultimate target.” Many publications noted that satire in the movies was usually box-office poison, but Kubrick’s film was breaking new ground in many ways. It was considered newsworthy enough that it was included on the cover of Time magazine’s year-end issue under the title “The Nuclear Issue.” And in the wake of the themes of both Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove, the U.S. Air Force released a statement reassuring the world that there were “safeguards” in place, which would preclude the kind of mishaps depicted in the films.

Kubrick’s cast choices for Dr. Strangelove followed paths as interesting as his plotlines.

Peter Sellers had worked with Mr. Kubrick two years earlier in the offbeat hit Lolita. This time the producer-director would require of his star a tour-de-force that would challenge any actor: he would play three disparate roles. Sellers took it in stride. He had been on stage since he was a child, traveling with his parents’ comedy act. He had been a radio and film star in the U.K. since the late 1940s, often using disguises to play multiple parts in comedy sketches. He would consider it no stretch at all to be President Merkin Muffley, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, as well as the title character, Dr. Strangelove himself. Perhaps it should be pointed out that after this strenuous role, he plunged into three more American films in 1964, and while filming the last, Billy Wilder’s Kiss Me Stupid, he suffered a heart attack that set him back for some time. Sellers was replaced in the role by Ray Walston and would undertake a less hectic schedule for most of the sixteen years of life that were left to him.

Second-billed was George C. Scott, a veteran marine who had worked his way through the acting trenches via theater and television. Moviegoers first saw him in 1959 in a fine performance as a prosecutor in Anatomy of a Murder and in a low-key Gary Cooper Western, The Hanging Tree. His next two projects were equally memorable, The Hustler in 1961, in which he was a smooth villain, and in 1963, the star-studded mystery The List of Adrian Messenger.

The world did not yet know the intense imperatives that burned in Mr. Scott and would burst into headlines when, six years later, he denounced the Academy Award ceremonies as akin to beauty pageants and said if he were to receive one, he would refuse to accept it. He did receive it for 1970’s Patton and he did refuse to accept it. A model of consistency, he also received a television Emmy for his work in Arthur Miller’s The Price and he refused that award as well.

Obviously, Mr. Kubrick knew something about George Campbell Scott that the audience did not. Those complex performances were wrenched from a complex man whose rage we no longer have to guess at.

Mr. Kubrick’s next choice was an old colleague from his first days as a filmmaker, Sterling Hayden. Mr. Hayden was another veteran marine but was personally a more adventurous soul than Mr. Kubrick, Mr. Sellers, or Mr. Scott. Twelve years older than Kubrick and nine years older than Scott, Hayden brought a wealth of life experience to any role.

He was born Sterling Relyea Walter in 1916 in Montclair, New Jersey. He dropped out of school at age sixteen to go to sea. He later said he was actually the captain of a schooner by the time he was twenty-one. What is clear is that he never lost his obsession with the sea. He was, in fact, trying to buy his own schooner when an agent suggested he might try modeling for extra cash. Sterling was 6’5″ and handsome, and the agent was not the first to suggest he try cashing in on his looks.

The modeling led in short order to a contract with Paramount and a temporary farewell to the sea. A bewildering series of events followed. He made his first film—Virginia—in 1941. After Pearl Hafbor was bombed, he married one of the screen’s true beauties, Madeleine Carroll, quickly made two more films, then just as quickly volunteered for the U.S. Marines.

Even that wasn’t quite enough action for him, so when “Wild Bill” Donovan called for volunteers from among the ranks for an organization known as OSS, the Office of Strategic Services, for extremely dangerous duty, he signed on immediately.

His assignment was to coordinate the activities of partisans behind the German lines in Greece and Yugoslavia. It was in the latter country that he established close ties with Yugoslav fighters under a man named Josip Broz, who had since 1935 called himself “Tito.” Tito was a Communist, but what impressed Hayden and other Allied agents was that his soldiers killed Nazis as opposed to the other Yugoslav partisans, the Chetniks, who often collaborated with the occupiers and spent as much time fighting Tito as the Germans.

Hayden came to admire the spirit and the camaraderie he saw among Tito’s troops, as well as their sense of purpose. For a time, he ascribed it to their politics. When he returned to the U.S.A. after the war and was discharged from service, he joined the Communist Party. Within six months he became disillusioned and left the organization.

By 1947, he was back at Paramount making movies. He surprised everyone by the depth of his performance in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle in 1950.

It was then that he came afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee. After being summoned several times, he agreed to appear before the panel. Like director Elia Kazan and many others, he admitted he had been a party member, briefly, and went on to name several colleagues in Hollywood who also had been members. Most had already been named, but some had not. Those who knew him best said he never got over his decision to name names. It saved his career, but apparently changed forever his view of himself. His pursuit of parts was thereafter desultory, stopping entirely for large chunks of time when he took to the sea by himself or with family members. His autobiography, Wanderer, was ostensibly about his sailboat with that name, but it clearly defined him as well. His General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove—and the method of his character’s death—shows quite as many dimensions and lights and shadows as did Mr. Scott’s performance.

In some ways, Mr. Kubrick’s most unusual casting choice created the indelible image of the movie.

Slim Pickens had been a rodeo clown, which accounts for his professional name. Born Louis Bert Lindley Jr., he was on the rodeo circuit from the time he was twelve. Headlining as a clown led to movie work when he was thirty years old. For the first fourteen years of his Hollywood career, Mr. Pickens was cast in one forgettable Western after another. For a time, he seemed lost on an endless “trail” with South Pacific Trail (1952), Iron Mountain Trail (1953), and Old Overland Trail (1953). Thirty-one of these horse operas later, he found himself cast in the important role of Major T. J. “King” Kong, pilot of the plane that would send the world to its doom, all the time just “doing his duty.”

“Well, boys, I reckon this is it; nuclear combat toe to toe with the Russkies.”

That’s how we meet Major Kong as he—mistakenly—tells his crew of their mission.

This role lifted Mr. Pickens into a new category. After Dr. Strangelove, he would make 40 more movies, many of them big- budget star turns, including In Harm’s Way, Major Dundee, the remake of Stagecoach, Will Penny, and Blazing Saddles.

Slim Pickens used his rodeo training to good advantage when he rode the atomic bomb down to its target, just like the runaway bronco it wag. That’s the freeze-frame we remember.

Not surprisingly, the praise for Dr. Strangelove was not unanimous. The Washington Post was of the opinion that “No Communist could dream of a more effective anti-American film than this one.” Bosley Crowther of the New York Times huffed, “I am troubled by the feeling, which runs all through the film, of discredit and even contempt for our whole military establishment.”

Actually, Mr. Crowther was right on the money. Stanley Kubrick did have distrust of, and probably contempt for, our military establishment—any military establishment. His deep cynicism and meticulous filmmaking style continued through his last work, Eyes Wide Shut, released the year of his death, 1999.

His body of work supports his dark view of life, from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clockwork Orange, to Full Metal Jacket. Unhappy with Hollywood’s filmmaking by committee, Kubrick went to England in 1961, where he felt he could work more independently. He remained there until his death.

In 1964, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science was not quite sure what to make of Dr. Strangelove. It was a success at the box office and that always counts in Hollywood.

Still, here was a film making brutal sport of our bulwark against mortal enemies. It was portraying our most cherished leaders as buffoons, not in the usually harmless parodies of Laurel and Hardy or Chaplin, but in sharp, savage satire.

On the other hand, it was obvious that Kubrick had struck a nerve. Millions were weary of being held prisoner in a twilight war that had no winners and for which no end was in sight. Looked at through the upside-down logic of satire, the whole thing was, well, foolish—tragically, comically, fatally foolish.

The clarion call of an antiwar movement had been sounded one year before Vietnam became the issue that would fuel that movement until it burned, for a time, out of control.

There were Oscar nominations for Best Picture; Best Actor— Peter Sellers; Best Director; Best Screenplay for Kubrick, Peter George, and Terry Southern. But in the year of My Fair Lady, there would be no statuettes for Dr. Strangelove. Kubrick would have to be content with his New York Film Critics Award as Best Director.

And, in the years to come, Kubrick would have to be content with taking responsibility for a film that—for good or ill— altered the public dialogue on the morality of the superpowers’ balance of terror.

Dr. Strangelove developed in us an embryonic skepticism for what was beginning to be called the “military establishment,” and it fostered a growing skepticism about authority everywhere.

In the years following Dr. Strangelove, the lines of national debate were skewed perceptibly. Like The Dictator twenty-four years earlier, Dr. Strangelove used humor to change us.

Source: Nick Clooney, The Movies That Changed Us: Reflections on the Screen