Politics in Coaxial America

A couple of years ago Robert Redford and director Michael Ritchie collaborated on Downhill Racer, a first-rate, totally unsentimental look at the life and the world of an Olympic skier. It was as sharply authentic as a fractured tibia but, in its sardonic way, much funnier.

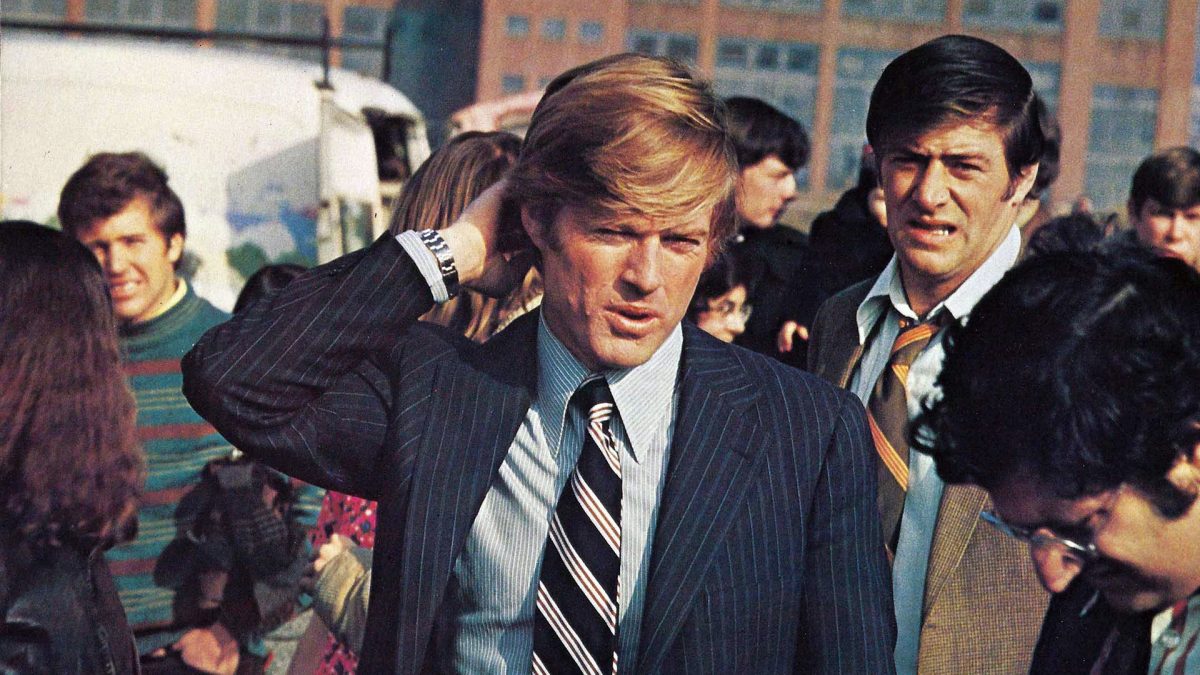

Now, in The Candidate, Redford and Ritchie have teamed again to deliver what I think is nothing less than the best movie yet done about politics in coaxial America.

Coming as it does amidst the smiling sonorities of a presidential year, The Candidate is seconded by every newscast. But The Candidate sees the candidate, and the campaign process, with a cool detachment the newscasts rarely manage.

The Candidate is almost totally devoid of the traditional melodramatics of smoke-filled rooms, deals or grown men playing with power blocs. And it’s not really the suspense story of the embattled idealist fighting the powers of darkness with the batteries failing in his loud-hailer.

What The Candidate is about is the process—the campaigning in the age of jets and television and pit stops rather than whistle-stops, but especially in the age of television—which makes all candidates politically equal in their inability to do much more than shake and smile and simplify and pray they have not become the most uncommon denominator.

The Candidate is impeccably credible, raucously funny and, in the end, frightening—frightening because the strong suggestion is that it is the clamorings of the public as much as the pressures of the electronic media which have reduced all ideas to simple syrup and concealed as much as they have revealed about the running men.

If The Candidate is not introspective, it still gives us the view from within. Ritchie himself was a media adviser to Senator John Tunney during his underdog campaign against George Murphy. The movie’s associate producer, Nelson Rising, ran the Tunney campaign (and engineered the spectacular rallies and parades which give the movie its awesome for-realness). The idea and the general shape of The Candidate began with Redford and Ritchie themselves; the script is by another veteran of the chicken-and-peas circuit—Jeremy Lamer, who was a leading speechwriter for Eugene McCarthy and who later wrote the novel and screenplay for Drive, He Said.

Redford himself is apolitical but fascinated by the whole subject of winning—anything—in America, and particularly by the problems of sustaining what might be called an equanimity of personal view despite the pressures of fame, fortune, ambition, and success, or the lack of it.

The Redford character—John McKay—is a charismatic young liberal who will inevitably provoke comparisons with Tunney most especially. The state is California, and the movie got to eighty-two locations in its forty-two days of shooting, including some ingeniously edited-in grab shots of Redford, presumably one of the dais guests at a real party banquet attended by McGovern, Humphrey and Mayor Yorty. But there are echoes as well of any of the Kennedys, or of any bright young idealistic newcomer to the political wars.

Redford/McKay is a public service lawyer, the son of a crusty old former governor (played briefly but indelibly by Melvyn Douglas). He runs an action center for Chicanos near San Diego. He wants, he thinks, no part of the hustings; but he’s hustled by a hard-eyed, idealistic professional campaign manager who believes that Redford could give the state’s senior and smooth right-wing Republican incumbent a run for the Senate.

Ritchie made his own dark-horse choices for the roles, all splendidly vindicated. The campaign manager, tough and unflappable, is Peter Boyle, bald, black-bearded, in racing-style glasses, bearing no resemblance whatever to the foul-mouthed construction worker of Joe. The senior Senator, a long way away from the comic foil of the old Ann Sothern Show, is Don Porter, silver-haired and level-gazed and so earnestly glib that you wonder why he hasn’t had his own state for years.

Allen Garfield, most recently seen in a comedy bit as a brassiere maker in Get to Know Your Rabbit, is a maker of political commercials, shrewd and cynical but dedicated to enlarging the possibilities of politics as the art of the possible.

As he did in Downhill Racer, Ritchie makes extremely effective use of nonactors, first-time actors or “naturals”—people doing their own thing in the context of the story. Another Tunney campaign aide (Michael Barnicle) plays an aide to Redford. A whole company of TV and print journalists make appearances, but with none of the grinning self-consciousness with which Hollywood scribes used to show up in bad Hollywood movies about Hollywood.

Maury Green is one of the interrogators on a televised debate which (shot months before) bears an uncanny spiritual affinity to the Humphrey-McGovern debates. Time bureau chief Don Neff and Times political writer Dick Bergholz push through the crowds and ride the press planes, and Bill Stout tosses it back to Walter Cronkite in New York as if he’d been doing it for years, which, of course, he has.

Larner’s script traces Redford from his primary beginnings as a stammering, dead-serious man who says what he thinks, including “I don’t know,” to the polished performer who knows far better than to say what he thinks and who has got The Speech down until it is as smooth, and as weighty, as a Ping-Pong ball. In one brutally amusing scene Redford, groggy with fatigue and furious with the wind-up doll he has become, slumps in the back seat of a car and parodies The Speech, storming that thou shalt not pit black against old or poor against white. He ends his campaign with a soaring but wholly calculated oration to a Teamsters convention (whose boss has effusively introduced him though they’ve just voiced their mutual contempt backstage).

Many of the fictional incidents had real-life origins. Redford and Porter both race to the Malibu fire (duplicated at a controlled burning of some ancient barracks on Angel Island near San Francisco) to make points. The incumbent wins the exposure as then-Senator Murphy did when he and Tunney visited the fire. Redford in a men’s room is accosted by a stranger who starts hurling obscenities at him, in a moment from a Gene McCarthy campaign.

As an idea, the film was pocked with potential pitfalls, which in my view’ have all been avoided. The stickiest going involves Redford’s relationship with his wife (played with the right patrician touch by a San Francisco actress, Karen Carlson, whose screen debut this is). But, after, unsettling hints that there might be a distracting subplot about love withering on the trail, The Candidate settles for an accurate if ambiguous study in which the wife becomes another resource in the campaign and has reason to love and hate it.

Another newcomer, Susan Demott, plays a svelte political groupie with whom Redford has a short and meaningless respite which the film, rightly, glances at in passing.

Political films have had a bad history in Hollywood, commercially if not artistically (and often both ways). Despite the presence of Redford, The Candidate was a hard sell. But it came in for $1.5 million, a staggeringly low sum, given the crowds and the tumult. It seems likely (and deserves) to do far better than the earlier political works, because it concerns not the melodrama of invisible politics but the visible politics of thirty-second spots (done for Redford /McKay by the San Francisco firm Medion, which has done many a primary plug this year), talk shows, debates and documentaries. It has a right-now urgency that is strong and compelling.

The Candidate re-creates the medium and the message superbly well, but it also leaves, in the cluttered silence of the deserted campaign headquarters, a profoundly disturbing question about the media which make it so appallingly easy to tell the customers what they want to hear—and so appallingly difficult (probably impossible) to tell them what they don’t want to hear.

Director Ritchie says, more than half-seriously, that he and Redford have now done two-thirds of a documentary trilogy about winning in America. He, in due time, would like to do the third leg. More power to them. There remain business, medicine, and much else.

There are fine and believable supporting performances from Quinn Redeker, Morgan Upton and Michael Lerner as staffers, Ken Tobey as a Teamster leader and Joe Miksak as a loser making an eloquent concession speech. Jenny Sullivan is a harried staff secretary and Robert De Anda is one of Redford’s associates in the days before the campaign.

The photography, which achieves an on-the-run feeling without the deliberate degrading of technique, is by Victor J. Kemper. Richard A. Harris and Robert Estrin were the editors.

John Rubinstein, who did part of the music for the forthcoming Redford film, Jeremiah Johnson, did all the music here, and it is abundant and good.

Redford’s own performance is almost too easy to take for granted, it is so right and natural. But in fact it may well be the best thing he has ever done. He is here not the grinning, laconic loner, word-shy to the point of speechlessness, but a manifestly intelligent, articulate, sensitive, life-sized, complicated individual susceptible of being captured by flattery and rendered petulant by frustration.

Before I found the dark at the end of the tunnel and turned to movie reviewing, I covered many a campaign, trailing Estes Kefauver into Nebraska hamlets so small they were last visited by advancemen for Chester A. Arthur. I can only tell you that Redford is the candidate and this is the world, exhausting and engrossing, in which stale cigar smoke is perfume, a cold hamburger rates three stars, and warm beer tastes fit for the gods.

Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1972