Art is, among other things, a source of comfort, of consolation, even of courage, and this side of art becomes especially important in times of trouble. Unfortunately, it is precisely in times of trouble that a good many people look to art for images of their own despair, for flattering reflections of their terror and their interior violence. You hear: “Only a disjointed (or a violent, or insane) world.” It is a profoundly philistine view, assuming that art has some grim debt to “real life” and placing it firmly in the service of the meanest imaginable idea of truth, yet artists continue to pander to it, or to be ensnared by it. In this respect, as in more obvious ones, the movies are peculiarly vulnerable to the demands of their presumptive audience, which may account in part for a vein of nastiness which has begun to run through serious moving-pictures: a strain of bully-love, and a tendency to treat the audience as an emotionally malleable object to be manipulated rather than as an active participant in the artistic event The human pain, wickedness, and foolishness which have always been the subjects of drama are coming to be treated as transcendent and absolute, which means we get more and more films constructed like the “battle conditioning” films to which I was subjected during World War II—images of viciousness presented so authoritatively as to obliterate the possibility of any humane context for them. Their implication is that human experience is definable in terms of violence—that the world consists of brutes and their brutalized victims.

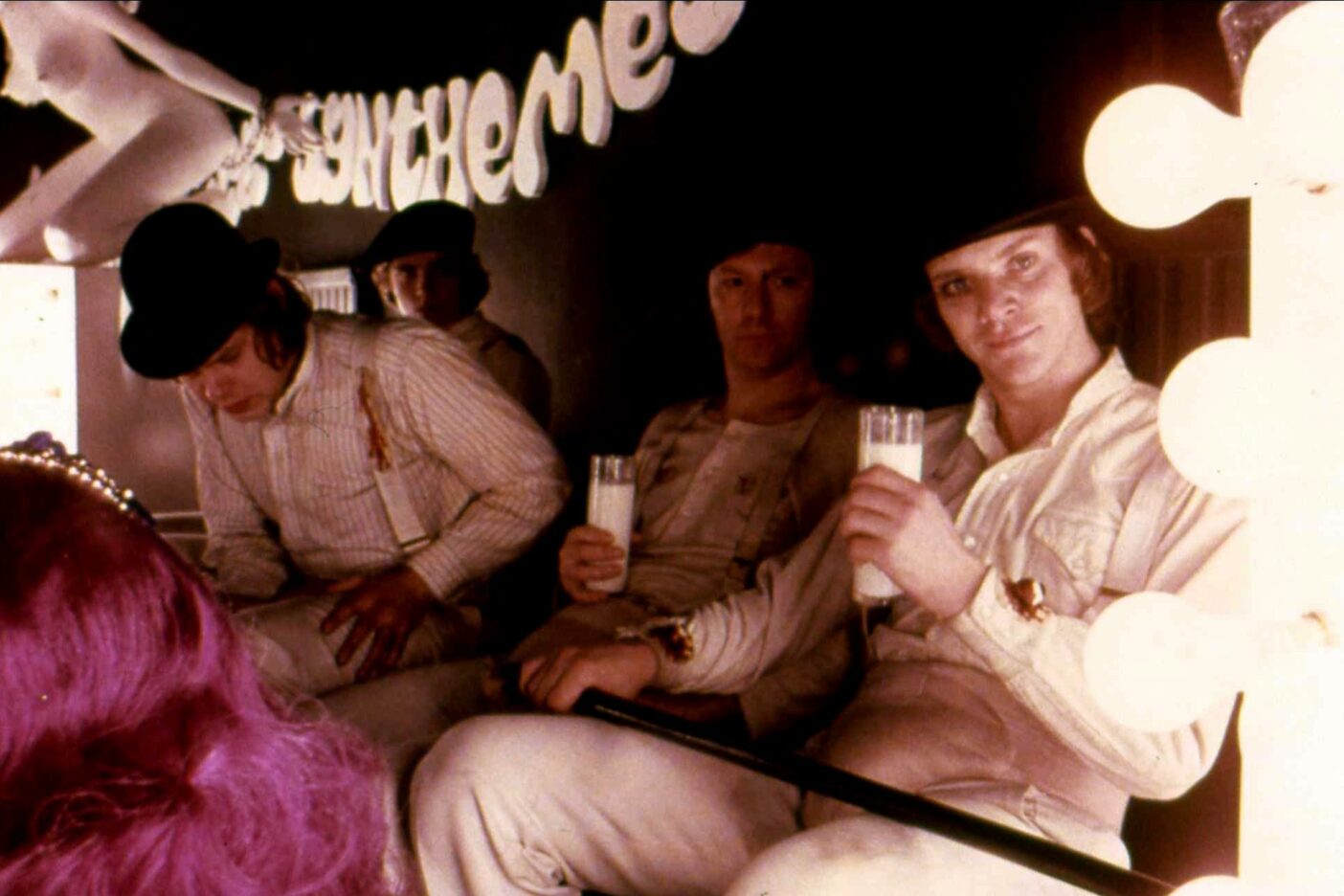

Well, if anybody is looking for a film which will embody and reinforce his worst moments of panic, it is available in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. It is the simple, fairytalelike story (taken from an Anthony Burgess novel) of a juvenile thug, Alex, who is imprisoned for murder, volunteers for “conditioning” to get out of jail, is conditioned to become sick at the prospect of sexual or aggressive action, and is then released to be abused by all his former victims. Hospitalized after a suicide attempt, he is “de-conditioned” by a government now fearful that he may prove an embarrassing example of its social engineering, and at the close of the film Alex, his thug-gishness fully restored, smiles wulfishly in the embrace of the slimy Home Secretary. The equation is clear and neat: the brutality of the fist differs little from the brutality of “law and order.” Except that that isn’t, in fact, Kubrick’s point. Quite clearly, he prefers the brutality of the fist, for Alex is made charming while the Home Secretary is thoroughly contemptible. Kubrick’s point is made earlier with the introduction of a prison chaplain who argues against conditioning on the ground that a man who loses the power to choose between good and evil has lost the chance of redemption, has lost his soul, has been de-humanized. Thus Alex, who has chosen to be evil, is better than all the mealy-mouthed others in the film who have either chosen evil pretending it is good or have timidly not chosen at all.

In fact, all of this logic-chopping doesn’t really function in the film at all. Kubrick said (in an interview with Penelope Houston of Sight and Sound) that Alex—whom he mysteriously compared with Richard III—is attractive for his “candor and wit and intelligence,” but then quickly gave the show away with “.. . and the fact that all the other characters are lesser people and in some way worse people.” The others in the film are all “lesser” in that they are less brutal, less physically strong, less ruthless, or take less joy in bloodshed. The means by which Alex is celebrated are simple enough: he is not made into a morally significant figure but into a comic hero. He is comic because he is so completely and maniacally what he is, and he is heroic because no other character is much of anything at all. The only gesture toward “significance” lies in giving Alex a deep and poetical sensitivity to music, and especially to Beethoven—which is spoiled for him during the conditioning when Beethoven is inadvertently mixed in with the things that make him sick.

The austere, symmetrical story unfolds in a strange, balletic style. Scenes are theatrically structured and photographed—even to two scenes being presented upon stages and another, a rape, done as a musical-comedy number. The sets are vaguely futuristic, but not very. All the usual reliance of movies upon circumstantial reality is dispensed with in favor of a stark, dreamlike quality enhanced by the choreographic integration of movement and score. The kind of thing Kubrick did with the spaceships in 2001, waltzing through the void, he here does, infinitely more subtly and imaginatively, with his actors, waltzing through an ethical and social void. The film is tersely and economically edited, and is fairly short, but it gives a curious feeling of gluey slowness at many points, for once Kubrick sets up a bit of violence he immediately goes stylized —slow-motion, balletic, or ritualized, but something intensely cinematic—and the effect is powerful.

The technical excellence of the film is no surprise. Kubrick can do everything well, and has an almost supernatural gift for pace and tempo, for the counterpoint of physical and emotional movement What did surprise me was the tawdrily fashionable quality of the film. I had gotten used to Kubrick working upon, around, and against convention: the conventional war film, love film, or science fiction film. In A Clockwork Orange he has put his great talents to the unquestioning service of a modish image: the sexually smoldering young brute. I guess they are the spawn of Stanley Kowalski. They multiply by the hundreds in television adventure series: slack-jawed and full-lipped, vaguely androgynous, their tight jeans bulging at the crotch, their nervous and strident musical themes blaring. Their sullen glance makes grown men sweat and tremble, and awakens in every woman her repressed desire to be dominated. Pretty infantile stuff at best, it has now been reduced to a cartoon. What on earth has prompted Stanley Kubrick to try to breathe life into this particular scarecrow?

Both Kubrick and his star, Malcolm McDowell, have referred to the picture as “satire,” so I guess their comic hero is supposed to hold something or other up to ridicule, although I can’t imagine what. Kubrick calls it (same interview) . . . social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioral psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots,” but you can’t satirize a question, only an answer. I guess he means his answer is “Yes” and he wants to make fun of those who would answer “No,” but the film really doesn’t clarify who he thinks these benighted beings are, why they love these toys, or what makes them ridiculous. Alex, God knows, is not the target of the satire, and the others Kubrick isn’t especially interested in.

As to the moral and psychological significance, they seem to me flimsy claims. The proposition that what is done to Alex is “worse” than what he does is nonsense in any ordinary human terms. A club over the head may be cruder than a syringe in the arm, but that doesn’t make it somehow more humanly personal. As for the sanctity of man’s right to choose evil, that’s superstition, for it amounts to dealing in a few selected religious terms (“evil” and “free will”) while conveniently leaving out the terms that make religion something more than superstition (“Providence,” for instance, and “salvation”).

What it really boils down to is forty minutes of seeing Alex torture people, and men forty minutes of seeing Alex tortured. He wins because he brings to his torturing more style than his tormentors, in their turn, can muster, since he is disinterested while they are moved either by conviction, ambition, or passion. Kubrick has suggested that the violence portrayed is somehow “sterilized” by the mythic stylization he has given it, but if anything the opposite is true. The stylization shifts your attention, in a sense, away from the simple physical reality of a rape or a minder and focuses it upon the quality of feeling: cold, mindless, brutality. The quality of feeling tends to get forgotten in the endless arguments about movie violence, which sometimes suggest that realism of treatment is an index of unwholesomeness. The feeling of this film is quiet hysteria, as if Kubrick were using Alex as a stick to beat not only totalitarian but the whole of the human race, especially including the audience. I don’t see where he’s standing to wield this weapon, and I don’t think he knows. In fact, I suspect there is nothing under his feet more substantial than an imperfect glimmering of Anthony Burgess’s fastidious Roman Catholicism.

Kubrick has long shown a horrified fascination with dehumanization: the vision of machinelike people, or man-like machines which mode our humanity. The tragedy of Paths of Glory (one of his best films) is not the killing of the three innocent men but the army’s way of doing it and how they are, before they die, robbed of whatever character they had, good or bad, and turned into little more than limp dolls borne by robotlike executioners to their ridiculous yet real execution. Dr. Strangelove (to my mind Kubrick’s masterpiece) plays maniacally upon all sorts of weird confusions of the human and the mechanical, from Keenan Wynn’s shooting a coke machine to Peter Sellers’s autonomous artificial arm. In these pictures, and in 2001, he explored images of dehumanization and set them in suggestive parallels, contrasts, and analogs, but he was never complacent. He was clearly out to unsettle his audience in those pictures; in A Clockwork Orange, he seems merely trying to hurt. Dr. Strangelove discovers and comically explores a division within each of us—a real division, already there; A Clockwork Orange simply pulls the levers of fear, which is a different thing. It’s a spook show. If it weren’t the work of a serious artist, and if it weren’t so painful, it would be trivial.

In morals, as in politics, human beings with fascinating regularity turn themselves into the thing they hate, and something of the sort has happened to Kubrick in this film. The technique of the picture is the technique of brainwashing: emotional manipulation on the most visceral level of feeling. The dynamics of the film is the dynamics of totalitarianism: all choices and all values are derived from fear. Courage, difficult and uncertain as it is, is still the only defense against the rule of fear, which brings me back to the subject of satire, for the laughter of satire is restorative and courageous, while the laughter of A Clockwork Orange is a mean and cynical snigger at the weakness of our own stomachs. Personally, I suspect that a weak stomach may do more to protect us against the horrors of the total state than any amount of medieval niggling about free will and natural depravity. A strong stomach is the first requirement for a storm trooper.

Visual horrors abound in A Clockwork Orange, yet the worst moment may not be any of the murders, rapes, tortures, or beatings, but the moment when you notice that the film’s monster, the manager of the aversion therapy to which Alex is subjected, has a Jewish name. Mere bad taste? Or the fearful symmetry of a nightmare?

Film Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Spring, 1972), pp. 33-36