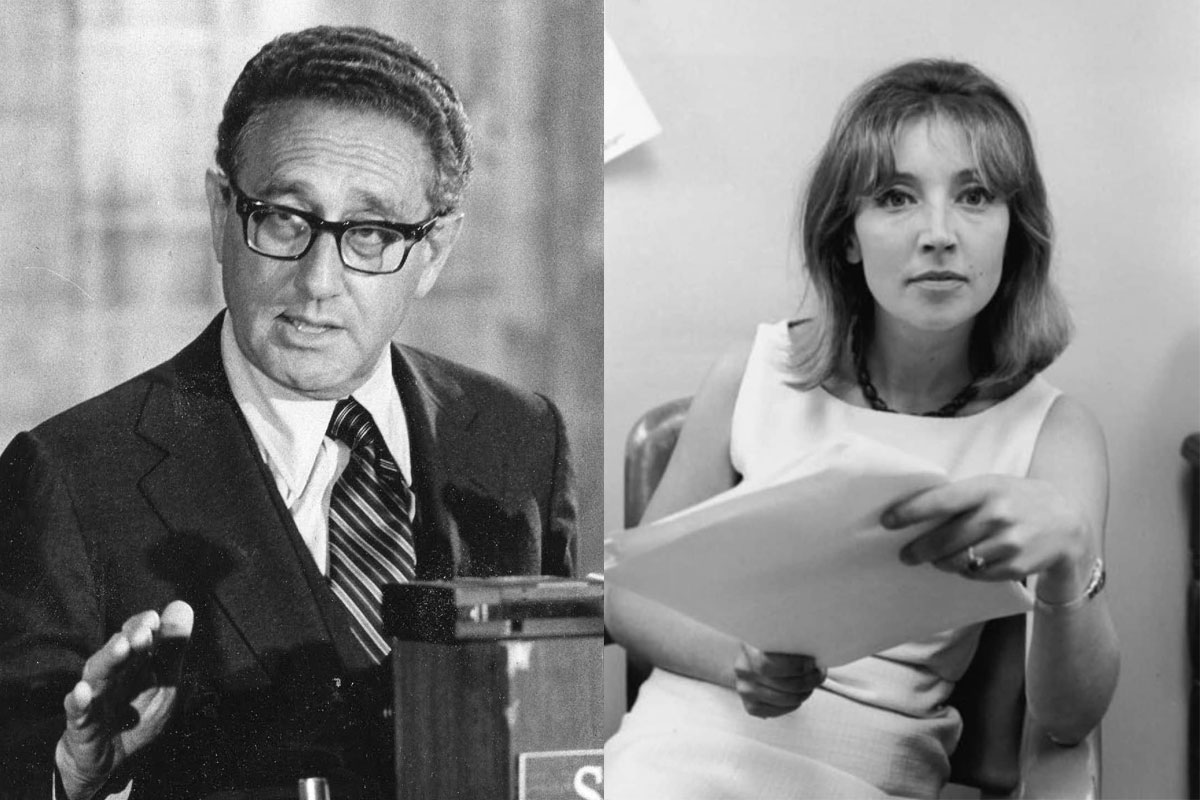

In the annals of journalistic history, few interviews have captured the public imagination quite like Oriana Fallaci’s 1972 encounter with Henry Kissinger, the enigmatic architect of American foreign policy. Their exchange was not merely a conversation; it was a clash of titans, a verbal sparring match that exposed the raw nerves of power and the complexities of war. Fallaci, the fiery Italian journalist, confronted Kissinger with a barrage of relentless questions, challenging his justifications for the Vietnam War and his role in the global political landscape. Kissinger, the shrewd statesman, parried her attacks with calculated responses, seeking to maintain his composure amidst the storm.

Henry Kissinger

by Oriana Fallaci

This too famous, too important, too lucky man, whom they call Superman, Superstar, Superkraut, and who stitches together paradoxical alliances, reaches impossible agreements, keeps the world holding its breath as though the world were his students at Harvard. This incredible, inexplicable, unbearable personage, who meets Mao Tse-tung when he likes, enters the Kremlin when he feels like it, wakens the president of the United States and goes into his bedroom when he thinks it appropriate. This absurd character with horn-rimmed glasses, beside whom James Bond becomes a flavorless creation. He does not shoot, nor use his fists, nor leap from speeding automobiles like James Bond, but he advises on wars, ends wars, pretends to change our destiny, and does change it. But still, who is Henry Kissinger?

Books are written about him as about those great figures whom history has by now digested. Books like the ones illustrating his political and cultural background, written by admiring university colleagues, or like the one celebrating his talents as a seducer written by a French newspaperwoman with an unrequited passion. With his university colleagues he never cared to speak. With the French newspaperwoman he never cared to make love. He alludes to them all with a vexed grimace and dismisses them with a scornful wave of his plump hand. “They understand nothing,” “None of what she says is true.”

The story of his life is the object of research bordering on a cult, simultaneously paradoxical and grotesque, so everyone knows that he was born in Fürth, Germany, in 1923, son of Louis Kissinger, a high-school teacher, and Paula Kissinger, a housewife. Everyone knows that his family is Jewish, that fourteen of his relatives died in the concentration camps, that together with his father and mother and his brother Walter he fled in 1938 to London and then to New York, that at that time he was fifteen years old and was called Heinz, not Henry, nor did he know a word of English. But he learned it very quickly, and while his father worked as a post-office clerk and his mother opened a bakery shop, he did so well at his studies that he was admitted to Harvard, where he graduated with honors with a thesis on Spengler, Toynbee, and Kant, and later became a professor.

Everyone knows that at twenty-one he was a soldier in Germany, where he was one of a group of GI’s selected by test and judged to have an IQ close to genius, that because of this (and despite his youth) he was entrusted with the job of organizing the government of Krefeld, a German city left without a government. Indeed it was in Krefeld that his passion for politics flowered, a passion that was to be gratified by his becoming an adviser to Kennedy and Johnson, later the presidential aide to Nixon, finally his secretary of state, until he came to be considered the second most powerful man in America. And already at that time, some maintained that he was much more, as is shown by the joke that for years made the rounds of Washington. “Just think what would happen if Kissinger died. Richard Nixon would become president of the United States!”

They used to call him Nixon’s mental wet nurse. They had even coined a wicked and revealing surname for him and Nixon: Nixinger. They said that Nixon could not do without him; that he wanted him always at his side on every trip, for every ceremony, every official dinner, every vacation. Above all, for every decision. If Nixon decided to go to Peking, thereby dumbfounding both the right and left, it was Kissinger who had put the idea in his head. If Nixon determined to go to Moscow, thereby confounding East and West, it was Kissinger who had suggested it. If Nixon announced reaching an agreement with Hanoi that would abandon Thieu, it was Kissinger who had persuaded him to take this step. Thus Kissinger acted as an ambassador, a secret agent, a negotiator, a Mazarin, a Metternich, a veritable president who used the White House as his own house.

Kissinger did not sleep there, since he wouldn’t be allowed to bring in women, you would have said (he had not, as yet, married a former assistant of Nelson Rockefeller). For nine years he had created a myth of his amorous adventures and he carefully nourished it, always allowing himself to be seen with actresses, starlets, singers, models, women journalists, dancers, and millionairesses. Insatiable as a bull, though many did not believe such a myth and the skeptics claimed that he couldn’t care less about these women, he behaved this way as a game, conscious of the fact that it increased his glamour, his popularity, his photographs in magazines. In this sense, too, he was the most talked-about man in America, and the most fashionable. His thick glasses had created a fashion, his curly hair, his gray suits and blue neckties, his deceptively ingenuous air of one who has discovered life’s pleasures.

Then Nixon resigned in shame, unmasked and defeated by a secret Putsch that nobody will ever consider a Putsch. Some said, “This is the end of Kissinger too.” Well, it was not. Kissinger remained where he was, still a powerful secretary of state and the new mental wet nurse of Ford, as unshakable and indestructible as a rock, or a cancer. Had he managed this devious Putsch? Was he irreplaceable, as the new president had intimated while begging him to stay? The mystery arose and is left to history.

After all, the whole Kissinger case is a mystery. The man himself, as well as his unparalleled success, is unexplained. As often happens when someone becomes very popular and very important, the more you know about him, the less you understand. Besides, he protects the incomprehensibility of his phenomenon so well that trying to explain it becomes a fatiguing exercise bordering on the impossible. Very rarely does he grant personal interviews; he speaks only at press conferences arranged by the administration. And I swear that I will never understand why he agreed to see me, scarcely three days after receiving my letter, in which I had entertained no illusions. He says it was because of my interview with General Giap in Hanoi in February 1969. It may be so. But the fact remains that after his extraordinary “yes,” he changed his mind and decided to see me on one condition: that he would tell me nothing. During the meeting, I was to do the talking, and from what I said he would decide whether to grant me the interview or not. Assuming he could find the time. Yes, the time was found, the appointment made for Thursday, November 2, 1972, when I saw him arrive out of breath and unsmiling, and he said, “Good morning, Miss Fallaci.” Then, still without smiling, he led me into his elegant office, full of books and telephones and papers and abstract paintings and photographs of Nixon. Here he forgot about me, turned his back, and began reading a long typewritten report. Indeed it was a little embarrassing to stand there in the middle of the room, while he had his back to me and kept reading. It was also stupid and ill-mannered on his part. However, it allowed me to study him before he studied me. And not only to discover that he wasn’t attractive at all, so short and thickset and weighed down by a large head like a sheep, but to discover also that he is by no means carefree or sure of himself. Before facing someone, he needs to take time and protect himself by his authority, a frequent phenomenon in shy people who try to conceal their shyness and by this effort end by seeming rude. Or by really being rude.

After reading the typewritten report—meticulously and carefully, to judge by the time it took him—he finally turned to me and invited me to sit down on the couch. Then he took the adjacent armchair, higher than the couch, and from this privileged and strategic position began to ask me questions in the tone of a professor examining a pupil in whom he has little confidence. He reminded me of my mathematics and physics teacher at the Liceo Galilei in Florence, an individual I hated because he enjoyed frightening me by staring at me ironically from behind his spectacles. He even had the same baritone, or rather guttural, voice as this teacher, and the same way of leaning back in the armchair with his right arm outstretched, the gesture of crossing his legs, while his jacket was so tight over his stomach that it looked as though the buttons might pop.

If he intended to make me ill at ease, he succeeded perfectly. The nightmare of my schooldays assailed me to such a degree that, at each of his questions, I thought, Oh, God, will I know the answer? Because if I don’t, he’ll flunk me. His first question was about General Giap. “As I’ve told you, I never give personal interviews. The reason why I’m about to consider the possibility of granting you one is that I read your interview with Giap. Very interesting. What is Giap like?” He asked it with the air of having little time at his disposal, so I had to sum it all up in a single effective remark, and answered, “He seemed to me a French snob. Jovial and arrogant at the same time, but actually as boring as a rainy day. It was less an interview than a lecture. I couldn’t get excited about him. Still what he told me turned out to be true.”

To minimize the figure of Giap in the eyes of an American was almost an insult; they were all a little enamored of him as they were thirty years ago of Rommel. The expression “French snob” therefore left Kissinger bewildered. Perhaps he did not understand it. The revelation that he was “as boring as a rainy day” disturbed him; he knows that he himself carries the stigma of being a boring type, and his blue eyes flashed twice with hostility. The detail that struck him the most, however, was that I gave Giap credit for having predicted things correctly. Indeed he interrupted me: “Why true?” I replied that Giap had announced in 1969 what would happen in 1972. “For example?” For example the fact that the Americans would withdraw little by little from Vietnam and would end by abandoning a war that was costing them more and more money and had soon brought them to the brink of inflation. The blue eyes flashed again. “And what, in your opinion, was the most important thing that Giap told you?” His having essentially disavowed the Tet Offensive by attributing it to the Vietcong alone. This time he did not comment. He only asked, “Does he think that the initiative was started by the Vietcong?” “Perhaps, yes, Dr. Kissinger. Even children know that Giap likes tank engagements a la Rommel. In fact the Easter offensive was carried out a la Rommel and …” “But he lost!” he protested. “Did he really lose?” I replied. “What makes you think that he didn’t lose?” “The fact that you have accepted an agreement that Thieu doesn’t like, Dr. Kissinger.”

In an attempt to draw some information out of him, I added in a distracted tone, “Thieu will never give in.” He fell into my little trap. He answered, “He’ll give in. He has to.” Then he concentrated on Thieu, his mare’s-nest. He asked me what I thought of Thieu. I told him that I had never liked him. “And why have you never liked him?” “Dr. Kissinger, you know better than I. You tried for three days, or rather four, to get something out of him.” This drew from him a sigh of assent and a grimace that, in retrospect, is surprising. Kissinger knows perfectly how to control his features; it seldom happens that his eyes or lips betray an idea or feeling. But during that first meeting, for some reason he made little effort to control himself. Every time I said something against Thieu, he nodded or smiled with complicity.

After Thieu he asked me about Nguyen Cao Ky and Do Cao Tri. Of the first he said that he was weak and talked too much. Of the second he said he was sorry not to have known him. “Was he really a great general?” Yes, I confirmed, a great general and a courageous one, the only general whom I had seen go to the front lines and into combat. For this too, I suppose, they had assassinated him. Here he pretended astonishment. “Assassinated? By whom?” “Certainly not by the Vietcong, Dr. Kissinger. The helicopter didn’t crash because it was hit by mortar fire, but because someone had tampered with the blades. And certainly Thieu did not shed any tears over that crime. Nor did Cao Ky. A legend was being built up around Do Cao Tri, and he spoke so badly of Thieu and Ky. Even during my interview with him, he attacked them mercilessly.” And this answer disturbed him more than the fact that I later criticized the South Vietnamese army.

This is what happened when he asked me about the last time I had been to Saigon, about what I had seen, and I replied that I had seen an army that wasn’t worth a fig, and his face assumed a perplexed expression. Indeed, since I was sure that he was putting on an act, I joked. “Dr. Kissinger, don’t tell me you need me to find out these things. You who are the most well-informed person in the world!” But he did not understand my irony and continued to question me as if the fate of the cosmos depended on my judgments, or as if he could not live without them. He knows how to flatter with diabolical, hypocritical—or should I say diplomatic?—finesse.

After fifteen minutes of conversation, when I was biting my nails for having accepted this absurd interview from the man I was supposed to interview, he forgot a little about Vietnam, and, in the tone of a zealous reporter, asked me which heads of state had impressed me most. (He likes the word “impress.”) Resigned, I listed them. He agreed with me primarily on Bhutto. “Very intelligent, very brilliant.” He did not agree about Indira Gandhi. “Did you really like her?” He didn’t even try to justify the unfortunate choice he had suggested to Nixon during the Indo-Pakistani conflict, when he sided with the Pakistanis who were to lose the war against the Indians who were to win it. Of another head of state, of whom I had said that he did not seem to me highly intelligent but that I had liked him very much, he said, “It’s not intelligence that’s important in a head of state. The quality that counts in a head of state is strength. Courage, shrewdness, and strength.”

I consider this remark one of the most interesting things he said to me, with or without the tape recorder. It illustrates his type, his personality. The man loves strength above all. Courage, shrewdness, and strength. Intelligence interests him much less, though he himself possesses it abundantly, as everyone says. (But is it a matter of intelligence or of erudition and cunning? The intelligence that counts, as far as I’m concerned, is the humane kind, that which is born from the understanding of men. And I wouldn’t say that he has that kind of intelligence. So on this subject one ought to go a little deeper. Assuming it’s worth the trouble.)

The last phase of my examination emerged from a question that I really didn’t expect. “What do you think will happen in Vietnam with the cease-fire?” Taken by surprise, I told him the truth. I said what I had written in a dispatch just published in L’Europeo: there would be a great bloodbath, on both sides, and the war would go on. “And I’m afraid that the first to begin the bloodbath will be your friend Thieu.” He jumped up, almost offended. “My friend?” “Well, anyway, Thieu.” “And why?” “Because even before the Vietcong embark on their slaughter, he will carry out a secret massacre in his prisons and jails. There will not be many neutralists or many Vietcong to form part of the provisional government after the cease-fire. …” He frowned, looked perplexed, and finally said, “So you too believe in the bloodbath… . But there will be international supervisors!” “Dr. Kissinger, even in Dacca there were the Indians. But they didn’t succeed in stopping the Mukti Bahini from slaughtering the Biharis.” “I know, I know, and if… What if the armistice were delayed for a year or two?” “What, Dr. Kissinger?” “What if the armistice were delayed for a year or two?” he repeated. A perfect example of his shrewd use of flattery: he couldn’t care less about my opinion. And yet, I fell for the ploy. I could have bitten my tongue, I could have wept. Indeed I think my eyes were wet when I looked at him again. “Dr. Kissinger, don’t make me suffer from the thought that I’ve put a wrong idea in your head. Dr. Kissinger, the mutual slaughter will take place anyway—today, in a year, two years. And if the war goes on another year or two, besides the dead from that slaughter, we will have to count those from the bombing and fighting. Do I make myself clear? Ten plus twenty makes thirty. Aren’t ten victims better than thirty?”

Stupidly unaware that he had made fun of me, I lost two nights of sleep over this, and when we met again for the interview I told him so. But he consoled me by saying that I shouldn’t upset myself by feeling guilty, that my mathematical calculation was correct, better ten than thirty, and this episode too illustrates his type and personality. The man likes to be liked, so he listens to everything, records everything like a computer. And just when it seems that he has discarded some now old and useless piece of information, he brings it forth as though it were valid and up to date.

After about twenty-five minutes, he decided that I had passed my examination. But there remained one detail that bothered him a little: I was a woman. It was with a woman, the French journalist who had written the book, that he had had an unfortunate experience. Supposing, despite my good intentions, I too were to cause him embarrassment? At this point I got angry. Certainly I couldn’t tell him what was on the tip of my tongue, namely that I had no intention of falling in love with him. But I could tell him other things, and I did. That I was not going to put myself in a situation like the one in which I found myself in Saigon in 1968 when, due to the poor figure cut by a cowardly Italian, I had had to put on a stupid display of heroics. That Mr. Kissinger should understand that I was not responsible for the bad taste of a lady who happened to be in the same profession as my own. So I shouldn’t have to pay for that, but, if he liked, I would wear a false mustache the next time we met.

He agreed to let me interview him, without smiling, and announced that he would find an hour on Saturday. And at ten o’clock, Saturday, November 4, I was back at the White House. At ten-thirty I entered his office to begin perhaps the most uncomfortable and the worst interview that I have ever had. God, what a chore! Every ten minutes we were interrupted by the telephone, and it was Nixon who wanted something, asked something, petulant, tiresome, like a child who cannot be away from its mother. Kissinger answered attentively, obsequiously, and the conversation with me was interrupted, making the effort to understand him still more difficult. Then, just at the high point, when he was setting forth for me the elusive essence of his personality, one of the telephones rang and again it was Nixon. Could Dr. Kissinger look in on him a minute? Of course, Mr. President. He jumped up, told me to wait, saying he would still try to give me a little time, and left. And thus ended our meeting. Two hours later, while I was still waiting, his assistant, Dick Campbell, came in all embarrassed and explained that the president was leaving for California and that Dr. Kissinger had to go with him. He would not be back in Washington before Tuesday evening, in time for the first election returns, but it was extremely doubtful that he would be able to conclude the interview at that time. If I could wait until the end of November, when many things would be clearer …

I couldn’t, and anyway it wasn’t worth the trouble. What was the point of trying to clarify a portrait that I already had before me? A portrait emerging from a confusion of lines, colors, evasive answers, reticent sentences, irritating silences. On Vietnam, obviously, he could not tell me anything more, and I am amazed that he had said as much as he had: that whether the war were to end or go on did not depend only on him, and he could not allow himself the luxury of compromising everything by an unnecessary word. About himself, however, he didn’t have such problems. Yet every time I had asked him a precise question, he had wriggled out like an eel. An eel icier than ice. God, what an icy man! During the whole interview he never changed that expressionless countenance, that hard or ironic look, and never altered the tone of that sad, monotonous, unchanging voice. The needle on the tape recorder shifts when a word is pronounced in a higher or lower key. With him it remained still, and more than once I had to check to make sure that the machine was working. Do you know that obsessive, hammering sound of rain falling on a roof? His voice is like that. And basically his thoughts as well, never disturbed by a wish or fantasy, by an odd design, by a temptation of error. Everything in him is calculated, controlled as in the flight of an airplane steered by the automatic pilot. He weighs every sentence down to the last ounce, no unintentional words escape him, and whatever he says always forms part of some useful mechanism. Le Due Tho must have sweated blood in those days, and Thieu must have found his cunning sorely tried. Kissinger has the nerves and brain of a chess player.

Naturally you will find explanations that take into consideration other aspects of his personality. For example, the fact that he is unmistakably a Jew and irreparably a German. For example, the fact that, as a Jew and German, transplanted to a country that still looks with suspicion on Jews and Germans, he carries on his back a load of knotted contradictions, resentments, and perhaps hidden humanity. In fact, they attribute to him boundless gifts of imagination, unappreciated talents for greatness. Could be. But in my eyes he remains an entirely common man and the most guilty representative of the kind of power of which Bertrand Russell speaks: “If they say ‘Die’, we shall die. If they say ‘live’, we shall live.”

Let us not forget that he owes his success to the worst president that the United States has ever had: Nixon, trickster and liar, sick in his nerves and perhaps in his mind, who has come, despised by all, to an undignified end. Let us not forget that he was, and still is, Nixon’s creature. If Nixon had not existed, probably we would never even have known that Kissinger had been born. For years Kissinger had been offering his services to two other presidents, neither of whom took him seriously. He was picked up by a governor who most certainly did not shine with acute brilliance and had arrived at political prominence only because of his billions: Nelson Rockefeller. Later Rockefeller had recommended him to Nixon, and the latter, in his ignorance, had been seduced by the pompous erudition of the German professor. Or was it by his totalitarian theses on the balance of the great powers, a laborious dusting-off of the Holy Alliance? Theirs was a meeting of two arrogant minds that believed neither in democracy nor in the changing world. And in that sense it was a successful meeting, so successful that the ease with which Kissinger abandoned Nixon when the latter fell into disgrace and shame seems truly astonishing. So far as I know, he did not even take the trouble to pay a visit to his Pygmalion who lay “dying” in a California hospital. He didn’t even bother to say a few words in his defense, to assume any responsibility for the misdeeds of which he was surely not ignorant and that he had probably endorsed. He went over bag and baggage to his successor, Ford, and merrily continued his career as secretary of state.

Let’s put it this way: he is an intellectual adventurer. And there would be nothing wrong in his being an intellectual adventurer (many great men and many great politicians have been—I would say almost all) if he succeeded in living in his own time and inventing something new, instead of going back to the decrepit concepts of his erudition or to personages who are in every sense defunct. Instead he is a man who lives in the past, without understanding the present and without divining the future. Much as he denies it, he really believes himself to be the reincarnation of Metternich, that is to say an individual who depended only on himself to arrange matters while basing his actions on secrecy, absolutism, and the ignorance of people not yet awakened to the discovery of their rights. And it is for this reason that Kissinger’s successes always turn out to be brief and accidental: a flash in the pan or smoke in the eyes. It is for this reason that in the long run each of his undertakings, each of his expectations, fails, and he commits such gross errors. His peace in Vietnam did not resolve the problem or even the war. In Vietnam, after the armistice, the fighting and dying continued; in Cambodia (where he and Nixon had brought the war) there was never a moment of truce. And finally it ended as it did, because his peace accords were a fraud. A fraud to save Nixon’s face, bring home the American boys, the POW’s, withdraw the troops, and erase the uncomfortable word “Vietnam” from the newspapers.

And his mediation between the Arabs and Israelis? Extolled and publicized as it has been, it has not lightened the tragedy of the Middle East by an ounce and if anything has worsened matters for the proteges of the United States. Since he began meddling in that part of the world, the conflict has grown and a war has broken out, Arafat has been received at the UN as a head of state, and Hussein has been deprived of all rights to the West Bank. And the Cyprus drama? It was precisely under Kissinger that the Cyprus drama exploded, with all its consequences. Did Kissinger know or not know that the fascist junta in Athens was preparing that invasion? If he knew, he was a fool not to understand the mistake. If he didn’t know, he was a bad secretary of state and even lacked the information that he boasts of having. And, in any case, the Cyprus drama deprived him of valuable allies: the Greek colonels. In abdicating they left Greece on the brink of war with Turkey. Constantine Karamanlis left NATO, and the Turks threatened to do likewise. What American, before Kissinger, has ever found himself with two NATO countries preparing to go to war and with the Atlantic Alliance made to look so ridiculous?

And then on Kissinger lies the horrible stain known as Chile. The documents that have appeared in the American press prove, beyond any possibility of denial, that it was Kissinger as well who wanted the overthrow of the democratic regime in Chile, the end of a democratically elected government. They also prove that Kissinger unleashed the CIA against Salvador Allende Gossens, that Kissinger financially helped those who were preparing the coup d’etat. There are many who wonder if, like Macbeth, he is not troubled at night by a bloody ghost of Banquo: the ghost of Allende. No toasts with Chou En-lai and Leonid Brezhnev will ever be able to wash away the suspicions that lie on him for Allende’s death. Nor does it help to see how generously Kissinger behaves with Franco and Franco’s Spain, deaf to the future that a democratic Spain prepares for herself in spite of Ford’s visits. It is almost unbelievable how this shaker of Communist leaders’ hands shows his esteem and friendship only for the countries ruled by some form of Fascism. And it is poor consolation to go on saying that his star is declining, that perhaps it has already set, that it is history that will have the final say on this too famous, too important, too lucky man whom they called Superman, Superstar, Superkraut.

* * *

Published in its entirety in the weekly New Republic, quoted in its more salient moments in the Washington and New York dailies, and then by almost all the newspapers in the United States, the interview with Kissinger kicked up a fuss that amazed me as much as its consequences. Obviously, I had underestimated the man and the interest that flourished around each of his words. Obviously, I had minimized the importance of that unbearable hour spent with him. In fact it immediately became the topic of the day. And the rumor soon spread that Nixon was enraged with Henry, that he therefore refused to see him, that in vain Henry telephoned him, asking for a hearing, and went to seek him out in his San Clemente residence. The gates of San Clemente remained closed, the hearing was not granted, the telephone went unanswered because the president did not care to answer. The president, among other things, did not forgive Henry for what Henry had said to me about the reason for his success: “… that I’ve always acted alone. Americans like that immensely. Americans like the cowboy who leads the wagon train by riding ahead alone on his horse, the cowboy who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else. …” Even the press criticized him for this.

The press had always been generous with Kissinger, merciless toward Nixon. In this case, however, the sides were reversed and every newspaperman condemned the presumption, or at least the imprudence, of such a statement. How did Henry Kissinger dare to assume the whole credit for what he had achieved as Nixon’s envoy? How did he dare to relegate Nixon to the role of spectator? Where was the president of the United States when the little professor entered the village to arrange things in the style of Henry Fonda in a Western film? The crueler newspapers published cartoons showing Kissinger dressed as a cowboy and galloping toward a saloon. Others showed a picture of Kissinger in cowboy hat and spurs, with the caption ‘‘Henry, the Lone Ranger.” An exasperated Kissinger let himself be questioned by a reporter, to whom he said that receiving me had been “the stupidest thing in his life.” Then he declared that I had garbled his answers, distorted his thoughts, embroidered on his words, and he did so in such a clumsy way that I became angrier than Nixon and took the offensive. I sent him a telegram to Paris, at the American embassy, where he happened to be at the moment, and in substance I asked him if he were a man of honor or a clown. I even threatened to make public the tapes of the interview. Mr. Kissinger should not forget that it had been recorded on tape and that this tape was at the disposal of everyone to refresh his memory and the exactness of his words. I made the same declaration to Time magazine, Newsweek, the CBS and NBC television networks, and to anyone who came to ask me about what had happened. And the altercation went on for almost two months, to the unhappiness of both of us, especially me. I could no longer stand Henry Kissinger; his name was enough to upset me. I detested him to such a point that I wasn’t even able to realize that the poor man had had no other choice but to throw the blame on me. But certainly it would be incorrect to say that at that time I wished him all success and happiness.

The truth is that my anathemas have no effect. Very soon Nixon stopped looking askance at his Henry and the two of them went back to cooing like a pair of doves. Their cease-fire was accomplished. The American prisoners returned home. Those prisoners who were such a pressing issue for Mr. Nixon. And the reality of Vietnam became a period of waiting for the next war. Then, a year later, Kissinger became secretary of state in place of William Rogers. In Stockholm they even gave him the Nobel Peace Prize. Poor Nobel. Poor peace.

ORIANA FALLACI: I’m wondering what you feel these days, Dr. Kissinger. I’m wondering if you too are disappointed, like ourselves, like most of the world. Are you disappointed, Mr. Kissinger?

HENRY KISSINGER: Disappointed? Why? What has happened these days about which I should be disappointed?

O.F.: Something not exactly happy, Dr. Kissinger. Though you had said that peace was “at hand,” and though you had confirmed that an agreement had been reached with the North Vietnamese, peace has not come. The war goes on as before, and worse than before.

H.K.: There will be peace. We have decided to have it and we will. It will come within a few weeks’ time or even less; that is, immediately after the resumption of negotiations with the North Vietnamese for the final accord. This is what I said ten days ago and I repeat it. Yes, we will have peace within a reasonably short period of time if Hanoi agrees to another meeting before signing the accord, a meeting to settle the details, and if it accepts this in the same spirit and with the same attitude that it held in October. These “ifs” are the only uncertainty these days. But it is an uncertainty that I don’t even want to consider. You’re letting yourself succumb to panic, and in these matters there is no need to succumb to panic. Nor even to impatience. The fact is that … Well, for months we have been conducting these negotiations and you reporters haven’t believed us. You’ve kept saying that they would come to nothing. Then, all of a sudden, you shouted about peace being already here, and now finally you say the negotiations have failed. In saying this, you take our temperature every day, four times a day. But you take it from Hanoi’s point of view. And… mind you, I understand Hanoi’s point of view. The North Vietnamese wanted us to sign on October 31, which was reasonable and unreasonable at the same time and… No, I don’t intend to argue about this.

O.F.: But you had committed yourselves to sign on October 31!

H.K.: I say and repeat that they were the ones to insist on this date, and that to avoid an abstract discussion about dates that at the time seemed entirely theoretical, we said that we would make every effort to conclude the negotiations by October 31. But it was always clear, at least to us, that we would not be able to sign an agreement whose details still remained to be clarified. We would not have been able to observe a date simply because, in good faith, we had promised to make every effort to observe it. So at what point are we? At the point where those details remain to be clarified and where a new meeting is indispensable. They say it’s not indispensable, that it’s not necessary. I say that it is indispensable and that it will take place. It will take place as soon as the North Vietnamese call me to Paris. But this is only November 4, today is November 4, and 1 can understand that the North Vietnamese don’t want to resume negotiations just a few days after the date on which they had asked us to sign. I can understand their postponing things. But I, at least, cannot conceive their rejecting another meeting. Just now when we have covered ninety percent of the ground and are about to reach our goal. No, I’m not disappointed. I will be, certainly, if Hanoi should break the agreement, if Hanoi should refuse to discuss any changes. But I can’t believe that, no. I can’t even suspect that we’ve come so far only to fail on a question of prestige, of procedure, of dates, of nuances.

O.F.: And yet it looks as though they’ve really become rigid, Dr. Kissinger. They’ve gone back to a hard line, they’ve made serious, almost insulting, accusations against you… .

H.K.: Oh, that means nothing. It’s happened before and we never gave it any importance. I would say that the hard line, the serious accusations, even the insults, are part of the normal situation. Nothing has changed essentially. Since Tuesday, October 31, that is ever since we’ve calmed down here, you reporters keep asking us if the patient is sick. But I don’t see any sickness. And I really maintain that things are going to develop more or less as I say. Peace, I repeat, will come within a few weeks after the resumption of negotiations. Not within a few months. Within a few weeks.

O.F.: But when will the negotiations be resumed? That’s the point.

H.K.: As soon as Le Due Tho wishes to see me again. I’m here waiting. But without feeling anxious, I assure you. For God’s sake! Before, two or three weeks used to go by between one meeting and another! I don’t see why now we should be upset if a few days go by. The only reason that you’re all so nervous is that people are wondering, “But will they resume these talks?” When you were all cynical and didn’t believe that anything was happening, you never realized that time was passing. You were too pessimistic in the beginning, then too optimistic after my press conference, and now again you’re too pessimistic. You can’t get it into your heads that everything is proceeding as I had always thought it would from the moment I said that peace was at hand. It seems to me I then figured on a couple of weeks. But even if it should take more … That’s enough, I don’t want to talk any more about Vietnam. I can’t allow myself to, at this time. Every word I say becomes news. At the end of November perhaps … Listen, why don’t we meet again at the end of November?

O.F.: Because it’s more interesting now, Dr. Kissinger. Because Thieu, for instance, has dared you to speak. Look at this clipping from The New York Times. It quotes Thieu as saying: “Ask Kissinger on what points we’re divided, what are the points I don’t accept.”

H.K.: Let me see it… Ah! No, I won’t answer him. I won’t pay any attention to this invitation.

O.F.: He’s already given his own answer, Dr. Kissinger. He’s already said that the sore issue is the fact that, according to the terms accepted by you, North Vietnamese troops will remain in South Vietnam. Dr. Kissinger, do you think you’ll ever succeed in convincing Thieu? Do you think that America will have to come to a separate agreement with Hanoi?

H.K.: Don’t ask me that. I have to keep to what I said publicly ten days ago … I cannot, I must not consider an hypothesis that I do not think will happen. An hypothesis that should not happen. I can only tell you that we are determined to have this peace, and that in any case we will have it, in the shortest time possible after my next meeting with Le Due Tho. Thieu can say what he likes. That’s his own business.

O.F.: Dr. Kissinger, if I were to put a pistol to your head and ask you to choose between having dinner with Thieu and having dinner with Le Due Tho … whom would you choose?

H.K.: I cannot answer that question.

O.F.: And if I were to answer by saying that I’d like to think you’d more willingly have dinner with Le Due Tho?

H.K.: I cannot, I cannot… I do not wish to answer that question.

O.F.: So can you answer this question: did you like Le Due Tho?

H.K.: Yes. I found him a man very dedicated to his cause, very serious, very strong, and always polite and courteous. Also sometimes very hard, in fact difficult, to deal with, but this is something I’ve always respected in him. Yes, I have great respect for Le Due Tho. Naturally our relationship has been very professional, but I think … I think I’ve noticed a certain niceness that shines through him. It’s a fact, for instance, that at times we’ve even succeeded in making jokes. We said that one day I might go to teach international relations at the University of Hanoi and he would come to Harvard to teach Marxism-Leninism. Well, I would call our relations good.

O.F.: Would you say the same thing for Thieu?

H.K.: I have also had good relations with Thieu. At first …

O.F.: Exactly, at first. The South Vietnamese have said that you didn’t greet each other like the best of friends.

H.K.: What did they say?

O.F.: That you didn’t greet each other like good friends, I repeat. Would you care to state the opposite, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: Well … Certainly we had and have our own viewpoints. And not necessarily the same viewpoints. So let’s say that we greeted each other as allies, Thieu and I.

O.F.: Dr. Kissinger, that Thieu was a harder nut to crack than anyone thought has now been shown. So as regards Thieu, do you feel that you’ve done everything you could or do you hope to be able to do something more? In short, do you feel optimistic about the problem of Thieu?

H.K.: Of course I feel optimistic! I still have things to do. A lot to do! I’m not through yet, we’re not through yet! And I don’t feel powerless. I don’t feel discouraged. Not at all. I feel ready and confident. Optimistic. If I can’t speak of Thieu, if I can’t tell you what we’re doing at this point in the negotiations, that doesn’t mean I’m about to lose faith in being able to arrange things within the time I’ve said. That’s why it’s useless for Thieu to ask you reporters to make me spell out the points on which we disagree. It’s so useless that I don’t even get upset by such a demand. Furthermore I’m not the kind of person to be swayed by emotion. Emotions serve no purpose. Less than anything do they serve to achieve peace.

O.F.: But the dying, those about to die, are in a hurry, Dr. Kissinger. In the newspapers this morning there’s an awful picture: a very young Vietcong dead two days after October 31. And then there was an awful piece of news: twenty-two Americans dead in a helicopter downed by a Vietcong mortar, three days after October 31. And while you advise against haste, the American Defense Department is sending fresh arms and ammunition to Thieu. Hanoi is doing the same.

H.K.: That was inevitable. It always happens before a cease-fire. Don’t you remember the maneuvers that took place in the Middle East at the moment of the cease-fire? They went on for at least two years. You see, the fact that we’re sending more arms to Saigon and that Hanoi is sending more arms to the North Vietnamese stationed in South Vietnam means nothing. Nothing. Nothing. And don’t make me talk about Vietnam anymore, please.

O.F.: Don’t you even want to talk about the fact that, according to many, the agreement accepted by you and Nixon is practically a sellout to Hanoi?

H.K.: That’s absurd! It’s absurd to say that President Nixon, a president who in the face of the Soviet Union and Communist China and on the eve of elections in his own country has assumed an attitude of aid and defense for South Vietnam against what he considered a North Vietnamese invasion … it’s absurd to think that such a president could sell out to Hanoi. And why should he sell out just now? What we have done hasn’t been a sellout. It has been to give South Vietnam an opportunity to survive in conditions that, today, are more political than military. Now it’s up to the South Vietnamese to win the political contest that’s awaiting them. As we’ve always said. If you compare the accepted agreement with our proposals of May 8, you’ll realize that it’s almost the same thing. There are no great differences between what we proposed last May and what the draft of the accepted agreement contains. We haven’t put in any new clauses, we haven’t made other concessions. I absolutely and totally reject the notion of a “sellout.” But, really that’s enough talk now about Vietnam. Let’s talk about Machiavelli, about Cicero, anything but about Vietnam.

O.F.: Let’s talk about war, Dr. Kissinger. You’re not a pacifist, are you?

H.K.: No, I really don’t think I am. Even though I respect genuine pacifists, I don’t agree with any pacifist, and especially not with halfway pacifists: you know, those who are pacifists on one side and anything but pacifists on the other. The only pacifists that I agree to talk to are those who accept the consequences of nonviolence right to the end. But even with them I’m only willing to speak to tell them that they will be crushed by the will of the stronger and that their pacifism can only lead to horrible suffering. War is not an abstraction, it is something that depends on conditions. The war against Hitler, for example, was necessary. By that I don’t mean that war is necessary in itself, that nations have to make war to maintain their virility. I mean that there are existing principles for which nations must be prepared to fight.

O.F.: And what do you have to say about the war in Vietnam, Dr. Kissinger? You’ve never been against the war in Vietnam, it seems to me.

H.K.: How could I have been? Not even before holding the position I have today … No, I’ve never been against the war in Vietnam.

O.F.: But don’t you find that Schlesinger is right when he says that the war in Vietnam has succeeded only in proving that half a million Americans with all their technology have been incapable of defeating poorly armed men dressed in black pajamas?

H.K.: That’s another question. If it is a question whether the war in Vietnam was necessary, a just war, rather than … Judgments of that kind depend on the position that one takes when the country is already involved in the war and the only thing left is to conceive a way to get out of it. After all, my role, our role, has been to reduce more and more the degree to which America was involved in the war, so as then to end the war. In the final analysis, history will say who did more: those who operated by criticizing and nothing else, or we who tried to reduce the war and then ended it. Yes, the verdict is up to history. When a country is involved in a war, it’s not enough to say it must be ended. It must be ended in accordance with some principle. And this is quite different from saying that it was right to enter that war.

O.F.: But don’t you find, Dr. Kissinger, that it’s been a useless war?

H.K.: On this I can agree. But let’s not forget that the reason why we entered this war was to keep the South from being gobbled up by the North, it was to permit the South to remain the South. Of course, by that I don’t mean that this was our only objective. … It was also something more… But today I’m not in the position to judge whether the war in Vietnam has been just or not, whether our getting into it was useful or useless. But are we still talking about Vietnam?

O.F.: Yes. And, still speaking of Vietnam, do you think you can say that these negotiations have been and are the most important undertaking of your career and even of your life?

H.K.: They’ve been the most difficult undertaking. Also often the most painful. But maybe it’s not even right to call them the most difficult undertaking. It’s more exact to say that they have been the most painful undertaking. Because they have involved me emotionally. You see, to approach China was an intellectually difficult task but not emotionally difficult. Peace in Vietnam instead has been an emotionally difficult task. As for calling these negotiations the most important thing I have done… No, what I wanted to achieve was not only peace in Vietnam, it was three things. This agreement, the rapprochement with China, and a new relationship with the Soviet Union. I’ve always attached great importance to the problem of a new relationship with the Soviet Union. I would say no less than to the rapprochement with China and to ending the war in Vietnam.

O.F.: And you’ve done it. The coup with China has been a success, the coup with Russia has been a success, and the coup of peace in Vietnam almost. So at this point I ask you, Dr. Kissinger, the same thing I asked the astronauts when they went to the moon: “What next? What will you do after the moon; what else can you do besides your job as an astronaut?”

H.K.: Ah! And what did the astronauts say?

O.F.: They were confused and said, “We’ll see… I don’t know.”

H.K.: Neither do I. I really don’t know what I’ll do afterward. But, unlike the astronauts, I’m not confused by it. I have found so many things to do in my life and I am sure that when I leave this post … Of course, I’ll need some time to recuperate, a period of decompression. No one who is in the position I am can just leave it and start something else right away. But, as soon as I’ve been decompressed, I’m sure to find something that’s worth doing. I don’t want to think about it now, it could influence my … my work. We’re going through such a revolutionary period that to plan one’s own life, nowadays, is an attitude worthy of the nineteenth-century lower middle class.

O.F.: Would you go back to teaching at Harvard?

H.K.: I might. But it’s very, very unlikely. There are more interesting things, and if, with all the experience I’ve had, I didn’t find some way of keeping up an interesting life … it will really be my own fault. Furthermore, I’ve by no means decided to give up this job. I like it very much, you know.

O.F.: Of course. Power is always alluring. Dr. Kissinger, to what degree does power fascinate you? Try to be frank.

H.K.: I will. You see, when you have power in your hands and have held it for a long period of time, you end up thinking of it as something that’s due you. I’m sure that when I leave this post, I’ll feel the lack of power. Still power as an instrument in its own right has no appeal for me. I don’t wake up every morning saying, my God, isn’t it extraordinary that I can have an airplane at my disposal, that a car with a chauffeur is waiting for me at the door? Who would ever have said it was possible? No, such thoughts don’t interest me. And if I should happen to have them, they certainly don’t become a determining factor. What interests me is what you can do with power. Believe me, you can do wonderful things… Anyway it wasn’t a desire for power that drove me to take this job. If you look at my political past, you’ll see that President Nixon couldn’t have figured in my plans. I’ve been against him in a good three elections.

O.F.: I know. You once even stated that Nixon “wasn’t fit to be president.” Has this ever made you feel embarrassed with Nixon, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: I don’t remember the exact words I may have said against Richard Nixon. But I suppose I must have said something more or less like that since people go on repeating the phrase in quotation marks. Anyway if I did say it, that’s the proof that Nixon wasn’t included in my plans for gaining a high government position. And as for feeling embarrassed with him … I didn’t know him at that time. I had toward him the usual attitude of intellectuals, do you see what I mean? But I was wrong. President Nixon has shown great strength, great ability. Even by calling on me. I had never approached him when he offered me this job. I was astonished by it. After all he knew I had never shown much friendship or sympathy for him. Oh, yes, he showed great courage in calling me.

O.F.: He didn’t lose anything by it, Dr. Kissinger. Except for the accusation that’s made against you today, that you’re Nixon’s mental wet nurse.

H.K.: That’s a totally senseless accusation. Let’s not forget that before he knew me, President Nixon had been very active in foreign policy. It had always been his consuming interest. Even before he was elected, it was obvious that foreign policy was a very important matter for him. He has very clear ideas on the subject. He’s a strong man. Furthermore, you don’t become president of the United States, you don’t get nominated twice as a presidential candidate, you don’t survive so long in politics, if you’re a weak man. You can think what you like of President Nixon, but one thing is certain: you don’t twice become president by being someone else’s tool. Such interpretations are romantic and unfair.

O.F.: Are you very fond of him, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: I have great respect for him.

O.F.: Dr. Kissinger, people say that you care nothing about Nixon. They say that all you care about is this job and nothing else. They say you would have done it under any president.

H.K.: Instead I’m not at all sure that I would have been able to do with another president what I’ve done with him. Such a special relationship, I mean the relationship there is between me and the president, always depends on the style of the two men. In other words, I don’t know many leaders, and I’ve met several, who would have had the courage to send their aide to Peking without saying anything to anybody. I don’t know many leaders who would leave to their aide the task of negotiating with the North Vietnamese, while informing only a tiny group of people about it. Certain things really depend on the type of president; what I’ve done has been possible because he made it possible for me.

O.F.: And yet you were also an adviser to other presidents. Even presidents who were Nixon’s opponents. I’m speaking of Kennedy, Johnson …

H.K.: My position toward all presidents has always been to leave to them the job of deciding if they wanted to know my opinion or not. When they asked me for it, I gave it to them, telling them, indiscriminately, what I thought. It never mattered to me what party they belonged to. I answered questions from Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon with the same independence. I gave them the same advice. It’s true that it was more difficult with Kennedy. In fact people like to say that I didn’t get along with him. Well … yes, it was mostly my fault. At that time I was much less mature than now. And then I was a parttime adviser; you can’t influence the day-by-day policy of a president if you see him only twice a week when others see him seven days a week. I mean … with Kennedy and Johnson I was never in a position comparable to the one I have now with Nixon.

O.F.: No Machiavellianism, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: No, none. Why?

O.F.: Because at certain moments, listening to you, one might wonder not how much you have influenced the president of the United States, but how much Machiavelli has influenced you.

H.K.: In no way at all. There is really very little of Machiavelli that can be accepted or used in the modern world. The only thing I find interesting in Machiavelli is his way of considering the will of the prince. Interesting, but not to the point of influencing me. If you want to know who has influenced me the most, I’ll answer with the names of two philosophers: Spinoza and Kant. So it’s curious that you choose to associate me with Machiavelli. People rather associate me with the name of Metternich. Which is actually childish. On Metternich I’ve written only one book, which was to be the beginning of a long series of books on the construction and disintegration of the international order of the nineteenth century. It was a series that was to end with the First World War. That’s all. There can be nothing in common between me and Metternich. He was chancellor and foreign minister in a period when, from the center of Europe, you needed three weeks to go from one continent to another. He was chancellor and foreign minister in a period when wars were conducted by professional soldiers and diplomacy was in the hands of aristocrats. How can you compare that with today’s world, a world where there is no homogenous group of leaders, no homogenous internal situation, no homogenous cultural reality?

O.F.: Dr. Kissinger, how do you explain the incredible movie-star status you enjoy, how do you explain the fact that you’re almost more famous and popular than a president? Have you a theory on this matter?

H.K.: Yes, but I won’t tell you. Because it doesn’t match most people’s theories. The theory of intelligence, for example. And then intelligence is not all that important in the exercise of power, and often actually doesn’t help. In the same way as a head of state, a fellow who does my job doesn’t need to be too intelligent. My theory is completely different, but, I repeat, I won’t tell you. Why should I as long as I’m still in the middle of my work? Rather, you tell me yours. I’m sure that you too have a theory about the reasons for my popularity.

O.F.: I’m not sure, Dr. Kissinger. I’m looking for one through this interview. And I don’t find it. I suppose that at the root of everything there’s your success. I mean, like a chess player, you’ve made two or three good moves. China, first of all. People like chess players who checkmate the king.

H.K.: Yes, China has been a very important element in the mechanics of my success. And yet that’s not the main point. The main point … Well, yes, I’ll tell you. What do I care? The main point arises from the fact that I’ve always acted alone. Americans like that immensely. Americans like the cowboy who leads the wagon train by riding ahead alone on his horse, the cowboy who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else. Maybe even without a pistol, since he doesn’t shoot. He acts, that’s all, by being in the right place at the right time. In short, a Western.

O.F.: I see. You see yourself as a kind of Henry Fonda, unarmed and ready to fight with his fists for honest ideals. Alone, courageous …

H.K.: Not necessarily courageous. In fact, this cowboy doesn’t have to be courageous. All he needs is to be alone, to show others that he rides into the town and does everything by himself. This amazing, romantic character suits me precisely because to be alone has always been part of my style or, if you like, my technique. Together with independence. Oh, that’s very important in me and for me. And finally, conviction. I’ve always been convinced that I had to do whatever I’ve done. And people feel it, and believe in it. And I care about the fact that they believe in me—when you sway or convince somebody, you shouldn’t confuse them. Nor can you even simply calculate. Some people think that I carefully plan what are to be the consequences, for the public, of any of my initiatives or efforts. They think this preoccupation is always on my mind. Instead the consequences of what I do, I mean the public’s judgment, have never bothered me. I don’t ask for popularity, I’m not looking for popularity. On the contrary, if you really want to know, I care nothing about popularity. I’m not at all afraid of losing my public; I can allow myself to say what I think. I’m referring to what’s genuine in me. If I were to let myself be disturbed by the reactions of the public, if I were to act solely on the basis of a calculated technique, I would accomplish nothing. Look at actors. The really good ones don’t rely only on technique. They perform by following a technique and their own convictions at the same time. Like me, they’re genuine. 1 don’t say that all this has to go on forever. In fact, it may evaporate as quickly as it came. Nevertheless for the moment it’s there.

O.F.: Are you trying to tell me you’re a spontaneous man, Dr. Kissinger? My God, if I leave out Machiavelli, the first character with whom it seems to me natural to associate you would be some cold mathematician, painfully self-controlled. Unless I’m mistaken, you’re a very cold man, Dr. Kissinger.

H.K.: In tactics, not in strategy. In fact, I believe more in human relations than in ideas. I use ideas but I need human relations, as I’ve shown in my work. After all, didn’t what happened to me actually happen by chance? Good God, I was a completely unknown professor. How could I have said to myself: Now I’m going to maneuver things so as to become internationally famous? It would have been pure folly. I wanted to be where things were happening, of course, but I never paid a price for getting there. I’ve never made concessions. I’ve always let myself be guided by spontaneous decisions. One might then say it happened because it had to happen. That’s what they always say when things have happened. They never say that about things that don’t happen—the history of things that didn’t happen has never been written. In a certain sense, however, I’m a fatalist. I believe in destiny. I’m convinced, of course, that you have to fight to reach a goal. But I also believe that there are limits to the struggle that a man can put up to reach a goal.

O.F.: One more thing, Dr. Kissinger: but how do you reconcile the tremendous responsibilities that you’ve assumed with the frivolous reputation you enjoy? How can you get Mao Tse-tung, Chou En-lai, or Le Due Tho to take you seriously and then let yourself be judged as a carefree Don Juan or simply a playboy? Doesn’t it embarrass you?

H.K.: Not at all. Why should it embarrass me when I go to negotiate with Le Due Tho? When I speak to Le Due Tho, I know what I have to do with Le Due Tho, and when I’m with girls, I know what I must do with girls. Besides, Le Due Tho doesn’t at all agree to negotiate with me because I represent an example of moral rectitude. He agrees to negotiate with me because he wants certain things from me in the same way that I want certain things from him. Look, in the case of Le Due Tho, as in the case of Chou En-lai and Mao Tse-tung, I think that my playboy reputation has been and still is useful because it served and still serves to reassure people. To show them that I’m not a museum piece. Anyway, this frivolous reputation amuses me.

O.F.: And to think I believed it an undeserved reputation, I mean playacting instead of a reality.

H.K.: Well, it’s partly exaggerated, of course. But in part, let’s face it, it’s true. What counts is not to what degree it’s true, or to what degree I devote myself to women. What counts is to what degree women are part of my life, a central preoccupation. Well, they aren’t that at all. For me women are only a diversion, a hobby. Nobody spends too much time with his hobbies. And that I spend only a limited time with them you can see by taking a look at my schedule. I’ll tell you something else: it’s not seldom that I’d rather see my two children. I see them often, in fact, though not as much as before. As a rule, we spend Christmas together, the important holidays, and several weeks during the summer, and I go to Boston once a month. Just to see them. You surely know that I’ve been divorced for some years. No, the fact of being divorced doesn’t bother me. The fact of not living with my children doesn’t give me any guilt complexes. Ever since my marriage was over, and it was not the fault of either of us that it ended, there was no reason not to get divorced. Furthermore, I’m much closer to my children now than when I was their mother’s husband. I’m also much happier with them now.

O.F.: Are you against marriage, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: No. The dilemma of marriage or no marriage is one that can be resolved as a question of principle. It could happen that I’ll get married again … yes, that could happen. But, you know, when you’re a serious person, as, after all, I am, to live with someone else and survive that living together is very difficult. The relationship between a woman and a fellow like me is inevitably so complex… . One has to be careful. Oh, it’s difficult for me to explain these things. I’m not a person who confides in reporters.

O.F.: So I see, Dr. Kissinger. I’ve never interviewed anyone who evaded questions and precise definitions like you, anyone who defended himself like you from any attempt by others to penetrate to his personality. Are you shy, Dr. Kissinger?

H.K.: Yes. Fairly so. But as compensation I think I’m pretty well balanced. You see, there are those who depict me as a mysterious, tormented character, and those who depict me as an almost cheerful fellow who’s always smiling, always laughing. Both these images are incorrect. I’m neither one nor the other. I’m … I won’t tell you what I am. I’ll never tell anyone.

Washington, November 1972