The following text is the introduction to the volume Genocide in Satellite Croatia, 1941-1945. A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres. The American Institute for Balkan Affairs, 1961.

INTRODUCTION

by Edmond Paris

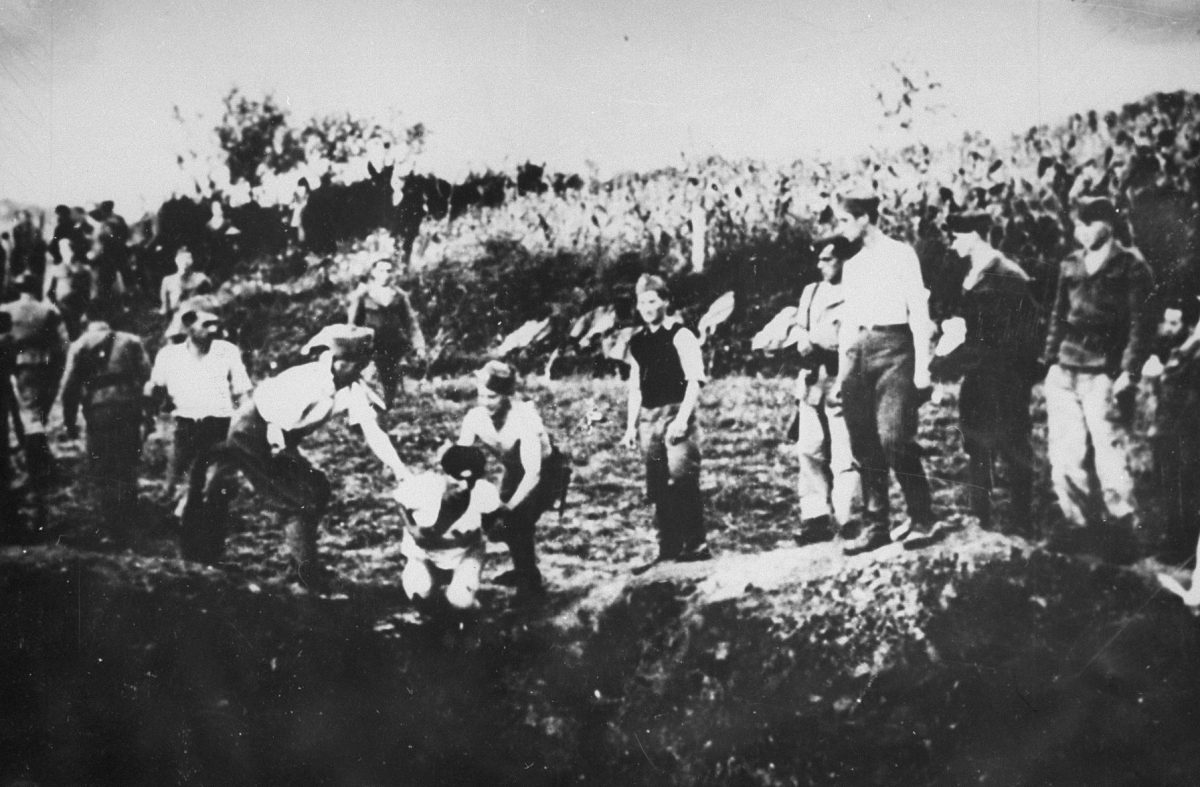

The greatest genocide during World War II, in proportion to a nation’s population, took place, not in Nazi Germany but in the Nazi-created puppet state of Croatia. There, in the years 1941-1945, some 750,000 Serbs, 60,000 Jews and 26,000 Gypsies— men, women and children—perished in a gigantic holocaust. These are the figures used by most foreign authors, especially the Germans, who were in the best position to know. Hermann Neubacher, perhaps the most important of Hitler’s troubleshooters in the Balkans, reports that although some of the perpetrators of the crime estimated the number of Serbs killed at one million, the more accurate figure is 750,000.1 One of Hitler’s generals, Lothar Rendulic, who was in the area where the crimes were committed, estimates that in the first year of the existence of the puppet state of Croatia at least a half million Orthodox Serbs were massacred, and that many others were killed in subsequent years.2 French writers most often use the half-million figure while British sources usually cite 700,000 Serbs killed.

The magnitude and the bestial nature of these atrocities makes it difficult to believe that such a thing could have happened in an allegedly civilized part of the world. Yet even a book such as this can attempt to tell only a part of the story.

The reader will no doubt ask: Why did it happen? The author believes that the reader himself must answer that question. But a brief account of the past may be of assistance. Because the victims were for the most part Serbs who belonged to the Serbian Orthodox Church, it seems desirable to indicate who the Serbs were, how they happened to live in these areas and what had been their relations with the other people in the same geographic region.

In the middle ages the Serbs had their own independent nation, occupying the area of what is now the southern part of Yugoslavia. After their defeat by the Turks at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, they began moving northward, entering regions then under the nominal rule of Hungary, hoping to live to fight another day on behalf of Christianity and freedom. This Serbian emigration reached considerable proportions after the fall of the Serbian ruler, Djurdja Brankovic (1459) and after the fall of Bosnia (1463) to the Turks.

The Hungarian kings used the emigrant Serbs in the struggles to defend their borders from the Turks, because the Serbs, already at that time, were known as able and competent soldiers. After Hungary united with Austria (1526), the Austrian rulers created a military belt stretching from the Adriatic Sea in the West to the Carpathian Mountains in the East, known as Vojna Krajina (literally military zone or region).

This region was populated chiefly by Serbs. Most of the Croatians, who were tenants of landed estates in this area, fled to Hungary, Austria, Italy, Bavaria or Croatia proper (Croatia had been absorbed in the twelfth century by Austria and Hungary). The Austrian rulers settled the depopulated areas with Serbs, who had come, not as refugees, but as warriors. They were given land (they became free peasant owners), but they had to promise that a certain number of men had to be under arms constantly. All men between 18 and 60 had to do military service whenever they were called.

Thus, the Serbs came to empty, deserted property. And the Austrian authorities were glad to have them, because they did not come as ordinary refugees, seeking merely to save their necks, but as warriors willing to continue the fight against the infidel Turk, in the eternal hope that one day Turkey would be defeated and they could return to their own lands. But the Turkish occupation was to last some five hundred years. In the meantime, the Serbs became valuable and respected citizens, settled in their new home, although they often had to pay a dear price for living on the frontier, exposed to periodic Turkish military onslaughts.

But the Serbs were also to face difficulties inside the Austrian and Hungarian kingdoms. To the north of them was Croatia proper, a strongly clerical land. Life was difficult there for anyone who was not a Roman Catholic. The Catholic bishops (from Zagreb and from Senj), with the help of Viennese Jesuits, sought constantly to convert the newly-arrived Serbs to Catholicism in the regions bordering on Croatia, or at least to get them to accept the Uniate rite. Many times those attempts were aided by military authorities using brute force, although the Austrian kings were officially and formally on the side of the Serbs.

In short, the Serbs in these regions were to be on the defensive for 350 years, trying to preserve their religion (Serbian Orthodox) and their national identity. Their right to own land and their right to work for the state were limited because they were not Catholics. Serbian priests were tortured and imprisoned because they refused to join the Uniates. These restrictions and persecutions have been described by Croatian and German (Austrian) historians. And they were admitted by the various official promises of rectification.

There was a considerable discrepancy between theory and practice. From time to time, the authorities promised autonomy and independence for the Orthodox Church. They even promised autonomy for Serbian civil authorities (e.g. Emperor Joseph of Hungary in 1706). And yet the military chaplain of Lika (Marko Mesic) could proclaim: “Be converted to Catholicism or get out!” Vienna could say one thing (how sincerely?), while local authorities could do another.

The Croatians feared the progress that the Serbs were making in all fields: religion, economics, education and culture. They were determined to do something about it. In the eighteenth century, for example, they instructed the Croatian representatives in the Hungarian parliament to seek the enactment of laws and regulations which would make life impossible for the Serbian people and for the Orthodox Church. Among the measures proposed were the following: to prevent the organization of Serbian high schools (the Croats did not yet have elementary schools in Croatian), to prevent the building of Orthodox Churches, to take away all property of Serbian monasteries, to prevent the collection of contributions for monasteries, to turn the Orthodox clergy over to the courts as ordinary trash, and to do away with the schism.

Maria Theresa, however, rejected these demands because Serbian military power was needed in the struggle against the Turks.

In the nineteenth century, this hatred for the Serbs, heretofore largely confined to the Catholic priesthood, was transferred to the Croatian people. To this end, Ante Starcevic, whom the Croatians called the father of his country, contributed the most. He is the first Croatian racist, putting forth the slogan: “The Serbs are a breed fit only for the slaughter house.” Subsequently, he put forth the saying: “Serbs to the willows,” meaning that the Serbs should be hung on willow trees.

Although there was a split among Starcevic’s followers, he succeeded in forming a political movement whose chief reason for existence was hatred of the Serbs. After his death, Starcevic was succeeded by Josef Frank, who entered into close collaboration with the Croatian clericals to form a Frankist party, which was under the direct influence of Vienna. To this extremist group belonged Ante Pavelic, who in 1941 was to arrive from Italy and with the aid of Fascist and Nazi power to become head of the Axis puppet state of Croatia, and soon thereafter the principal butcher of the Serbs. But this is getting ahead of the story.

In 1918, the Frankist party, which had in the past relied on Vienna for support, went out of existence. With the defeat of Austro-Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro joined with Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Herzegovina and other regions formerly under Austro-Hungarian rule to form a common state—Yugoslavia. In such circumstances there was no place for a Frankist party.

While the experience of a common nationhood for the Serbs and the Croats was in many ways a stormy one, and certainly beyond the possibility of adequate description here, two elemental points need to be made. First of all, in the political sphere, considerable progress was made in Serb-Croat relations prior to 1941. Secondly, in the religious sphere, the Roman Catholic Church enjoyed full freedom to pursue its activities and to prosper. These two points need further brief elaboration.

Yugoslavia became a political democracy. But Serbia, because of her previous existence as a nation (and consequently her greater political experience) and because the Serbs were more numerous than all of the other groups combined, had a dominant voice in the new nation’s political affairs. This led to some dissatisfaction, and subsequently to more extreme difficulties, resulting in the establishment of a dictatorship in 1929. In 1931, the dictatorship was modified to a degree, with minor modifications in the late thirties. In 1939, an agreement (Sporazum) was concluded between the government in Belgrade and the representatives of the Croatian Peasant party, abandoning the principle of a centralist state.

Under the Sporazum Croatia was granted extensive political and economic autonomy, with her own government and her own assembly. The central government still controlled foreign affairs and defense. Croatia was to have autonomy in internal administration, justice, public education, agriculture, forestry, mining, construction, finance, health and social policy. Her territory was enlarged, taking in over a million Serbs (under the Nazis it was to be enlarged still further). The head of the principal political party in Croatia (Croatian Peasant Party), Dr. Vlatko Macek, became vice-president of the central government. But the fanatics in Croatia could be satisfied with nothing short of the destruction of the Yugoslav state.

Parenthetically, it should be added that the Sporazum was received with dissatisfaction in Serbia. Serbs for the most part felt that the Croatians, a minority group, had been given rights which even the Serbs did not enjoy. The government was aware of this hostility and hence never submitted the Sporazum to the parliament for ratification.

On the religious front, the Roman Catholic Church had full freedom and equality from the beginning. Countless witnesses can testify to this fact, but it might be interesting to refer to one or two Catholic sources. A Croatian Catholic priest, Vjekoslav Wagner, spoke of the expansion of Catholicism in Serbia, adding that “such progress could be attained only in a country where religious tolerance and equality were living facts.”3 More recently, Belgian Catholics have reported how before the Second World War, the Catholic press (dailies, weeklies and monthlies) flourished in Yugoslavia, how Catholic schools, colleges and other religious centers functioned, how Catholic hospitals were built and Catholic organizations multiplied.4 Dr. Anton Korosec, cleric and Slovene Catholic leader, has admitted that “even without the Concordat the Catholic Church enjoyed full freedom of action.” 5

There are ample statistics on the progress of the Catholic Church in Yugoslavia between the two world wars, and any one really interested in checking them can easily do so.

Nevertheless, extremist clerical elements in Croatia were dissatisfied living in a country where the Catholics were in a minority. Perhaps they feared the future. To allay these fears, Belgrade governments were willing to expose themselves to hostility in Serbia and in other Serbian Orthodox regions by entering into a Concordat with the Vatican, which would formalize relations between the Church and the state. Belgrade hopedthat this would placate Croatian Catholic hostility toward the state and the government.

The Concordat was opposed in Serbia because it granted privileges and guarantees to the Catholic Church which the Orthodox themselves did not enjoy. For example, the state was obligated to pay the Catholic Church for properties confiscated by the Austrian state (1780-1790), something that even Catholic Austria had refused to do. Moreover, the state was to pay for land taken by agrarian reform measures, but only to the Catholic Church and not the others.

That the disputed Concordat gave the Catholic Church a privileged position was recognized by Archbishop Bauer of Zagreb and his vicar, Stepinac, in a declaration on March 31, 1936: “The Catholic Church is not at all opposed to the Serbian Orthodox Church also receiving all that it perhaps does not now have and which is guaranteed to the Catholic Church by the Concordat.” 6

Parenthetically, it might be added that many Croatian leaders, including the head of the Croatian Peasant party, Stjepan Radic, were not in favor of the Concordat. They feared the entrenchment of clericalism in Croatia, and believed that the Concordat would facilitate it.

But the Croatian extremists were interested only in separatism; they did not want a common state. In 1929, Ante Pavelic fled to Italy and there resurrected the Frankist party in the form of a terrorist organization, called the Ustashi. He became the leader of the Croatian extremist separatist movement. He received considerable help from Mussolini (25 million liras and a promise of liberal sums to come).7 He also received assistance from the Horthy regime in Hungary.

The members of Pavelic’s organization were recruited from the most viciously anti-Serb and the most depraved and sadistic elements in Croatia. They trained for and engaged in terrorist activities. The Ustashi sent assassins and terrorists into Yugoslavia, who blew up bridges, placed bombs in public places, and contributed to the death and injury of many innocent victims. The Ustashi also killed King Alexander of Yugoslavia and the French Foreign Minister, Louis Barthou, on October 9, 1934 in Marseilles.

When Hitler and Mussolini destroyed Yugoslavia in 1941, Pavelic and his Ustashi were brought in to rule an enlarged puppet state of Croatia. To tell what they did to the Serbian population under their jurisdiction is the task of this book. It is the author’s hope that these few pages will enable the reader to view the genocide in Croatia in some historical perspective. To see that it was not the result of a momentary disagreement with the Serbs or the result of a revolution. Rather it came as the consequence of a carefully prepared ideology which began in the second half of the nineteenth century and culminated in Pavelic’s Ustashi.

* * *

NOTES

1. Sonder-Auftrag Suedost 1940-1945: Bericht eines fliegenden Diplomaten (Goettingen—Berlin—Frankfurt, 1956). pp. 31-32.

Statement of Hermann Neubacher reads as follows:

The recipe for the Orthodox solution of the Ustashi-fuehrer and the Poglavnik (head of State) of Croatia, Ante Pavelic, reminds one of the bloodiest memories connected with Religious Wars: “One third must be converted to Catholicism, one third must leave the country, and one third must diel” The last point of this programme was carried out. When leading Ustashi state that one million of Orthodox Serbs (including babies, children, women and old men) were slaughtered, this, in my opinion, is a boasting exaggeration. On the basis of reports I received, I estimated that three quarters of a million defenseless people were slaughtered.

As I repeated once again at the Headquarters the reality of the horrible events which were taking place in my Croatian neighborhood, Adolf Hitler replied:

“I also told the Poglavnik that it is not so simple to annihilate such a minority, it is too large.”

2. Gekaempft Gesiegt Geschlagen (Heidelberg, 1952), pp. 161-62.

3. “Katolirizam u Srbiji” (Catholicism in Serbia), Almanah Jugoslovenske Katolicke akademije (1929), p. 3.

4. Une Eglise du silence—Catholiques en Yougoslavie (Brussels, 1954), pp. 144, 149.

5. Hrvatska Zora (Munich), September 1, 1954.

6. Sima Simic, Vatikan protiv Jugoslavije (The Vatican Against Yugoslavia), (Titograd, 1958), pp. 16-17, and Viktor Novak, Magnum Crimen (Zagreb, 1948), p. 440.

7. Hevre Lauriere, Assassins au Nom de Dieu (Paris, 1959), p. 17.

Source: Edmond Paris, Genocide in Satellite Croatia, 1941-1945. A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres. The American Institute for Balkan Affairs, 1961