A candid conversation with America’s superdad about his revolutionary true-to-life comedy series—and about racism, kids, humor and heroes

Go figure out America’s taste in television. Last year, just when the nation seemed hopelessly addicted to prime-time programs that featured equal measures of sex, greed and hair spray, along came “The Cosby Show”— an unlikely series about a black obstetrician and his family—and suddenly, network executives were proclaiming that sitcoms weren’t dead, after all. NBC, proud as a peacock at last, found itself presenting TV’s top-rated weekly comedy series, while comedian Bill Cosby, riding the biggest wave of his career, had become America’s favorite father figure.

As Dr. Heathcliff Huxtable, Cosby portrays a bright, funny physician who’s deeply in love with his lawyer wife, Claire, played by Phylicia Ayers-Alien. Their TV children— four daughters and one son—mirror the real-life set of siblings Cosby has sired with his wife of almost 22 years, the former Camille Hanks. On “ The Cosby Show,” Father knows best, but not to the point of parental infallibility: Cliff Huxtable often learns as much from his kids as they do from him. Some critics have carped that the show isn’t “black” enough, which is to say that Dr. Huxtable isn’t poor and doesn’t go around exchanging high fives each time he delivers a baby or a solution to a family problem. The Huxtable children, meanwhile (judging by current TV standards and practices), are just plain weird: They actually love and respect their parents. Most people are not put off by all that. As John J. O’Connor recently noted in The New York Times, “At a time when so many comedians are toppling into a kind of smutty permissiveness, Mr. Cosby is making the nation laugh by paring ordinary life to its extraordinary essentials. It is, indeed, a truly line development.” In a cover story, Newsweek suggested that Cosby’s magical rapport with children, huge popularity with grownups and fiercely creative imagination put him in the genius class.

How far Bill Cosby’s career will continue to develop is anybody’s guess, including the comedian’s. For more than 20 years, Cosby has been a show-business staple whose body of work now includes 20 comedy albums (five of which won Grammys), five TV series (he won three Emmys for “I Spy”), ten movies and thousands of performances as a stand-up comedian.

By now, you’re probably somewhat familiar with Cosby’s curriculum vitae: The eldest of three sons, he was born in Philadelphia on July 12. 1937. At Philly’s Germantown High School, he was an excellent athlete (captain of the track and football teams) but a dreadful student. After his sophomore year, Cosby joined the Navy, saw the world and then saw the light: He enrolled in Navy correspondence courses, earned his high school diploma and then wangled a track scholarship to Temple University. Three years later, he again dropped out of school, this time because his weekend appearances at various Greenwich Village night spots had made him a hot comedy commodity. In 1963, he recorded his first comedy album, won a Grammy for it and has never looked back. He later received a degree from Temple and then earned a master’s and a doctorate in education from the University of Massachusetts. Cosby’s 212-page dissertation was titled “The Integration of Visual Media via Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids into the Elementary School Culminating as a Teacher Aid to Achieve Increased Learning.” The net result is that the man known in showbiz circles as Cos is known in others as Dr. William H. Cosby, Jr. And Fat Albert, who still lives inside his creator’s head, is said to be very pleased.

To interview the 48-year-old performer, Playboy again teamed Cosby with free-lancer Lawrence Linderman, who conducted the magazine’s original “Playboy Interview” with him (and Tinderman’s first) in 1969. Linderman reports:

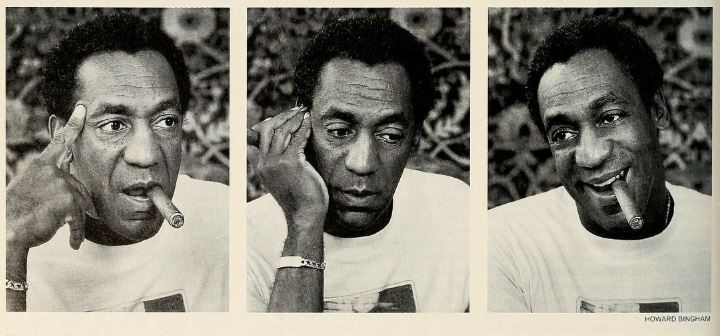

“I caught up with Bill a few weeks after ‘The Cosby Show’ had gone into its second season of production. Cosby was spending the last days of summer doing two shows a night at tent sites in Cohasset, Massachusetts, and Baldwin, Rhode Island, both within shouting distance of his 265-acre estate near Amherst, Massachusetts. When we got together at Kimball’s by the Sea, a snug little hotel in Cohasset Harbor, Cosby greeted me warmly, and I think both of us felt as if we’d seen each other only a few weeks before. Cosby hasn’t changed much over the years: The only signs he shows of advancing middle age are a slight tinge of gray hair and the beginnings of a paunch, which he’s busting his butt to eliminate. At our first meeting, we couldn’t find the source of the tiny chimes that were sounding in the room until Bill realized the sound was coming from a pair of stop watches he’d just bought to time himself in 400-meter runs. (Once a track man, always a track man.)

“In any case, when all the tootlings were done with, Cosby whipped out one of the foot-long Jamaican stogies he more or less chain smokes, and we got down to business. With the start of the new fall television season imminent, ‘The Cosby Show’ provided the opening subject for our conversation.”

PLAYBOY: The last time we spoke—in 1969—you were a hot young comedian. Since then, you’ve just about become a national institution. What does it feel like to be an American institution?

COSBY: Well, except for the fact that I was 16 pounds lighter 16 years ago, it feels good. It’s been good. I remember 1969 very well. Couple of things have happened since. [Grins through cigar smoke] Right about then. I had four albums in the top ten at the same time, and I don’t think even Elvis Presley ever did that. Now, that was a high. Winning the Em-mys was a high, then going on to do my TV specials. … I’ll tell you, when I was growing up in a lower-economic neighborhood in Philadelphia, these were things I thought happened only to people on the radio.

PLAYBOY: For readers who may not know that there was such a thing as life before television, what do you mean by that?

COSBY: Oh, old radio programs, like The Lux Radio Theater. The announcer would say, ‘‘There goes Humphrey Bogart” or “Sitting next to me is Edward G. Robinson.” I’d picture those guys in my mind—I’m sure they weren’t there—but that’s how some of all this feels. I know the TV series has changed things for me, but until it hit, I’d been very successful.

I consider myself a master of stand-up comedy, and I still really enjoy performing. I think even my commercials have been excellent, because I’ve done them only for products I believe in. But more than anything, I know how happy I am at home. My wife, Camille, and I are enjoying each other more and more, mostly because in the past eight or nine years, I’ve given up all of myself to her. I’m no longer holding anything back.

PLAYBOY: What part of you were you holding back?

COSBY: The part of me that was devoting more thought to my work than to my wife. That’s a very selfish thing to do, and I think there are people who’ll tell you quite openly that if they had to choose between their mate and their work, they’d choose their work. Well, eight or nine years ago, I realized that that was just silly, so I began releasing myself from my work—I’m not just talking about time now—and coming more and more together with my wife. And I found myself falling deeper and deeper in love with her.

I think the fear of giving all of myself to Camille also had to do with a worry that perhaps someday she would leave me; I was afraid that if I gave myself to her completely and she left, I’d have no hope of recovering. I always figured that maybe I should save 1 1 or 12 percent of myself to get me through that day when she says, “Look, Bill, I met a man while you were on the road and he’s a very nice guy.” When I realized what I was thinking, I thought, Well, if it happens, it happens, and I’ll deal with it then. But not now.

So it’s just pure and good with us. The children—some have their problems, but we’re able to work with them and talk with them, and they try. Can’t ask for more. So you’re looking at someone who was a very, very happy man before this series hit.

PLAYBOY: Despite all this success since we last spoke, there must have been moments that weren’t as upbeat as all that. Wasn’t there a time when Bill Cosby was in danger of going out of style?

COSBY: Oh, there was a point where the career—the performance, or comedy, career—began to have trouble. In the early Seventies, when the younger culture went into a kind of LSD period, a lot of legitimate showbiz people—Bill Cosby, Harry Belafonte, Andy Williams, even Johnny Mathis—began to feel like tumbleweed rolling through the back of the theaters. The economy was in a dip, our fans were becoming parents, the time seemed wrong. It was tough for a lot of us. I went to Las Vegas, worked Vegas. I worked conventions, one-nighters. . . .

PLAYBOY: But you were still a young man then, in your mid-30s.

COSBY: Yeah, but I was talking old. I was talking to audiences about my marriage, my kids—I was out of Fat Albert by then. I really didn’t want to do “I’m a child’’ anymore; I was more interested in the behavior of a parent toward a child.

PLAYBOY: And the times finally caught up with you. It’s being said that The Cosby Show may turn out to be the kind of comedic landmark that All in the Family was, so let’s spend some time on it. Few industry insiders expected it to survive its first season, let alone become the most popular series on television. Have you been surprised by the show’s success?

COSBY: Yes, it’s gone way past what I expected. All I really wanted to do was satisfy people who’d understand what I was trying to give them—a series about a family that seemed as real as you could get within the confines of television, without using vulgar or abusive language. And I wanted to show kids that their mothers and fathers could be very, very firm people, almost dogmatic, yet you’d still love them because they have tomorrow’s newspaper and what they’re saying has to do with their love and concern for you.

PLAYBOY: Your show went to the top of the ratings virtually from the start. What do you think accounts for its popularity?

COSBY: Well, if you look at Cliff Huxtable, you see an overachiever who knows that American society tends to say that certain people can’t do certain jobs because of their color or sex or religion. So people like Cliff work twice as hard to prove themselves. But the beautiful thing about Cliff is that he’s a man who truly loves his wife—all of her—and they both love their children. That’s really why people watch the show—because of the family. When the show is over, I think people have the reaction I have to it: I smile and feel good.

PLAYBOY: Are you trying to educate viewers as much as entertain them?

COSBY: Oh, absolutely. You mentioned All in the Family. See, the difference between Cliff and Norman Lear’s Archie Bunker is that I don’t remember Archie ever apologizing for anything, and it’s a point on our show that when Cliff or anybody else does something wrong, an apology is in order. For example, on a show we called “The Juicer,” the kids get into trouble with Cliff after they mess with this food processor he’s just bought. The kitchen ends up a mess, and each of the children is responsible for some part of what happened. But then the wife turns to Clift and says. “Who left the machine plugged in in the first place?” So what we’ve got here is three people who blew it in terms of responsibility, and they’re talking about it. Well, I love that.

Maybe I sound like someone who’s trying to sell something to an audience, but I do have a track record in education: I started with Sesame Street three weeks after it went on the air, and from there I went to The Electric Company and to Fat Albert and to a series about a teacher named Chet Kincaid, which ran on ABC for two years.

PLAYBOY: The idea for this show supposedly originated with Brandon Tartikoff, president of NBC Entertainment, who saw you do a monolog about your children on The Tonight Show. Is that true?

COSBY: Yes, but the genesis of the show was more complicated than that. About three years ago. I decided I wanted to do a TV show that all my children could watch without my wife and I worrying about how it would affect them. I’d heard a lot of people say, “I don’t want to let my children watch television,” and I was feeling the same way. The situation comedies all seemed to get their laughs by using euphemisms for sexual parts of the body—lots of jokes about boobs and butts. And if there was a detective show on—and I’m not talking about the Tom Selleck show now—you’d see cars skidding on two wheels for half a block, or else some cat would be dropping to his knees with a .357 Magnum or sticking the gun in somebody’s mouth. The language was getting tougher, the women were stripping down faster, and if you had a five-year-old daughter, she was watching men shooting bullets and drawing a lot of blood.

Let me jump way ahead of what we’re discussing for a second, because I want to tell you about a very crazy moment for me. When NBC eventually went with The Cosby Show, they asked me to speak to a big crowd of advertising people who were being introduced to the network’s ’84-’85 line-up of shows. Well, I start to talk to them about why I wanted to do another TV show, and on a screen right behind me, NBC is running film clips of its new shows, and I tell you, if they ran clips of seven cop stories, six of them had the cars on two wheels, the guy busting into the room with a big gun and somebody in a bathtub about to be blasted. I’m there looking at this stuff and thinking, My own network is the one I’m trying to kill off. I really did set out to change all that.

PLAYBOY: Did Tartikoff get in touch with you about your monolog?

COSBY: No, but word of his idea reached Marcy Carsey and Tom Werner, two young producers, and they set up a meeting with me. We agreed very quickly on the basics of the show: The mother and father would both be working, they’d love each other very much and they’d have four children living in their New York apartment. But whenever the children show up—well, as Frank Gifford says, that’s when the wheels come off. We were in complete agreement on everything until I mentioned the guy’s occupation.

PLAYBOY: They didn’t want a doctor?

COSBY: No, I wanted the guy to be a chauffeur. Marcy went crazy when I said that. She told me she couldn’t see me as a chauffeur, and I said, “Hey, chauffeurs make good money. The guy will own his own car, meaning he’ll be free to be at home at all kinds of weird hours—especially when his wife is working.”

PLAYBOY: Aren’t you glad you ran into Marcy Carsey?

COSBY: [Laughs] No, no. I’m not! And you should have heard the arguments we had when I decided I wanted my wife on the show to be a plumber or a carpenter! Well, I was arguing long and hard with Marcy and Tom, but I was standing tall. I think I could have gotten them to go along with me. But then I changed my mind.

PLAYBOY: Why?

COSBY: Because Camille, my wife of 22 years, said to me, “You will not be a chauffeur.’’ I said, “Why not?” And Camille said, “Because I am not going to be a carpenter.” I asked her, “What’s the problem here? Is there something wrong with being a chauffeur or a carpenter?” And she said, “Bill, of course there’s nothing wrong with those occupations—I’d be stupid if I thought that. But nobody is going to believe that you‘re a chauffeur. Your image has always been Temple University, college, grad school. Nobody’s going to believe it when you put on a uniform and stand beside a car and start polishing it. And people are going to laugh in your face when they see me with a hammer!” Well, I gave up on the idea right then and there.

PLAYBOY: Let’s see if we have this right: You ( hanged your mind because your wife felt that your TV wife’s occupation—and yours—wouldn’t square with the real image?

COSBY: Oh, no, I changed my mind not only because I absolutely trust Camille but also because at that point in the discussion, she had gotten upset with me. My wife doesn’t get upset about casual things, but now she was really upset; she was asking me to go visit a psychiatrist and bring back a note. Case closed. I went back and told lorn and Marcy they were right, and we changed Cliff’s occupation. Then they went up to Tartikoff with it and, boom, money came in and we did the show.

PLAYBOY: Who decided that Cliff Huxtable would be an obstetrician?

COSBY: I did. I wanted to be able to talk to women who were about to give birth and make them feel comfortable. I also wanted to talk to their husbands and put a few messages out every now and then.

PLAYBOY: Such as?

COSBY: That fathering a child isn’t about being a macho man, and if you think it is, you’re making a terrible mistake. It’s about becoming a parent.

PLAYBOY: Do you think you’ve succeeded in putting out those messages?

COSBY: Oh, sure. In one episode last season, a new husband comes into Cliff’s office and says, “I’m the man, the head of the household. Women should be kept barefoot and pregnant.” Cliff tells the guy that being a parent has nothing to do with that kind of concept of manhood. And he really straightens him out by telling him that neither he nor his wife will be in charge of the house—their children will. But this is an example of why I say I always felt the Huxtables’ jobs have very little to do with the show. It’s the behavior, the dealing with the children, the dealing with the wife that makes it work.

PLAYBOY: But just as Cliff’s profession gives him the opportunity to make certain points, doesn’t his wife do the same thing in her capacity as a lawyer?

COSBY: Yes, but I don’t think what she has to say emanates from a set of law offices. What I’m after is what happens to an individual. I’m not going after a broad social turnaround tomorrow. How can I put it? [Pauses] Look, I think I have faced these situations enough to say that if I threw a message out hard and heavy. I’d lose viewers. But if the message is subtle, people who want to find it will find it; and if they want to make changes, they will.

PLAYBOY: Which message do you mean?

COSBY: Any of them. Take the black female lawyer who’s been in a firm for seven years and is hoping for a promotion. . Generally, if you’re black and female in a white-male firm that you’ve been fortunate enough to get into, well, when you’re looking for that promotion and you don’t get it, you’re out. But if I put that on the show, my experience tells me no changes will come of it. So she got the promotion.

PLAYBOY: Since it obviously doesn’t always work that way in real life, can’t you be accused of giving viewers—especially in the example you just mentioned—a sugarcoated version of reality?

COSBY: It’s my position and feeling that if I put a situation that’s behaviorally negative on the show—let’s say Claire deserves the promotion and doesn’t get it—then I’ll be putting some lawyers on the defensive. And what’s the result? They’ll say, “Listen, I don’t want to hear this.” If somebody doesn’t want to give you something, they’re going to continue not to give it to you, regardless of what you say. And if they find you doing something they don’t like, they will at that point explain they were about to give it to you, but now that you’ve done something they don’t like, they won’t give it to you. It’s my Uncle Jack theory.

PLAYBOY: Care to tell us more about it?

COSBY: Well, I had an uncle Jack who owned a bicycle shop. The man knew that I loved bikes, and I’d go down to his shop on North Broad Street in Philadelphia and just salivate at the sight of all those bicycles. I was 12 years old and my uncle Jack knew how much I wanted a bike, but he’d never given me one. He let me ride bikes inside the shop, and one day I ran into his glass showcase and cracked it. Uncle Jack said to me, “Bill, I was going to give you a bike, but since you just broke my showcase, forget about it.”

Well, at the age of 12, I just said to myself, “Uncle Jack wasn’t going to give me a bike anyway.” That was a valuable lesson to learn.

PLAYBOY: And that has shaped your approach to dealing with social issues?

COSBY: Absolutely. By letting Claire get her promotion, I feel that when the show is rerun and rerun, there will be lawyers out there who’ll see it and who’ll maybe give a black, white or Asian female the promotion those women may deserve. We always try to put out a positive message, and all the people on that show arc very positive. The result is that we won’t have lawyers looking at the show and saying, “Don’t tell me the rotten guy who turned Claire down is me!” They’ll want to be smart, like the lawyer who gave her the promotion.

PLAYBOY: If we follow your reasoning, then, is it fair to say that The Cosby Show avoids presenting any rotten characters?

COSBY: I really try not to. I’d rather have people we all recognize and who, in their own way, are funny. For instance, this year, the Huxtables are making improvements in their house, and we’re introducing a contractor who’ll be on the show maybe five times. I love the character. The contractor comes in to look at the work Cliff wants done, and he tells him the three things contractors always tell you: “I don’t know how long it’s going to take. I don’t know what it’s going to cost. And I just don’t know when I’m going to get started, Dr. Huxtable.” I think people will look at him working in the Huxtables’ house—with cloths set up and dust rising and the kids flying around—and say. “Yeah, that’s happened to us.”

PLAYBOY: You’ve already mentioned the overlap your wife felt between your real family and your TV family: Do the Huxtables have four daughters and one son because Bill Cosby is the father of four daughters and one son?

COSBY: Oh, sure. What’s funny is that in the beginning, we all agreed that the Huxtables would have four children. We had excluded the character of my real daughter who’s away at college. It wasn’t until after we did the first show that I felt that my oldest daughter was missing—I really wanted her to be part of that family in terms of my ideas. Sondra Huxtable, who’s played by Sabrina LeBeauf, a very fine actress, is not our oldest girl. Erica. But in terms of having that family work, in terms of what I know, I needed an oldest daughter away at college. My only regret now is that we don’t give Sabrina enough work. At the writers’ meetings, I’ll say, “Now, look, somebody remind me that we’ve got to bring Sondra home. I want to see her.”

PLAYBOY: Do the Cosby children ever get upset because their father is duplicating or extending some of their own foibles on national television?

COSBY: No, because in my stand-up-comedy work, the children have already seen me talking about them and naming them and embellishing what they’ve said or done, and they’ve always been cool about it. Sometimes they even enjoy coming back to me and saying, “Oh, look, Dad, please, I don’t want people to think I’m like that.”

PLAYBOY: Some of the stories are straight out of real life, though, without embellishment, aren’t they?

COSBY: Oh, yeah. There’s a story I tell about my son, Ennis, walking around looking real thoughtful one day when he was 14. The boy obviously was working up the nerve to ask me for something big—a father knows that look. He finally came up to me and said, “Dad, I was talking to my friends, and they think that when I’m 16 and old enough to drive, I should have my own car.’’

“Fine. You’ve got wonderful friends,” I told him. “I think it’s terrific that they want to buy you a car.”

The boy looks at me in shock. “No, Dad, they want you to buy the car.”

This does not come as a shock to me. “What kind of car did you have in mind?” I ask.

“Gee, Dad, I think it would really be nice to have a Corvette.”

Can’t fault the boy’s taste in cars. I say to him, “Look, son, a Corvette costs about $25,000, and I can afford to buy you one. I ‘d like to buy you a Corvette— but not when you don’t do your homework and you bring home Ds on your report card. So I’ll make you a deal: For the next two years, you make every effort to fulfill your potential in school, and even though Corvettes will then cost about $50,000, I’ll buy you one. And I won’t even care if you do bring home Ds. If your teachers tell me you tried as hard as you could, and that you talked to them every time you had a problem with your work, well, if a D was the best you could do, I can’t ask any more of you. Just give a 100 percent effort in school for the next two years, and you’ve got yourself a Corvette.”

My son gets very quiet. Finally, he looks up at me and says, “Dad, what do you think about a Volkswagen?” Young Ennis, by the way, is now 6’3” tall.

PLAYBOY: Do you ever get out on a basketball court with him?

COSBY: No way. Ennis is much too quick and too strong for me. Listen, I run in a competition for older guys called the Masters, and if I can’t beat men my own age—which I can’t—what would I be doing going up against a 16-year-old kid? Ennis is a good athlete, but he’s a gentleman athlete. He’s not from the days of yesteryear, when you stayed out on the court for 17 hours even if the temperature reached 103 degrees. I mean, Ennis has sense.

PLAYBOY: More than you had as a child?

COSBY: No question. You know what my problem used to be—among others? Embarrassment when I found out that someone else was right and I was wrong. I’ll give you an example: When I was about 12, my grandfather said to me, “Don’t play football until you’re 21 years old.” Now. this was a man I loved and respected. I said, “Why, Granddad?” He said, “Because your bones won’t heal until you’re 21.”

Very quietly, I dismissed him. He was not a high school-educated man. This was a hard-working steel driver, Samuel Russell Cosby, but I said to myself, “This man is trying to stop me from doing something I want to do.” So I played football in junior high, I played it on the street, I played it in high school. Got on the football team at Philadelphia Central High School. First game, I jumped over a guy and cracked my humerus—my shoulder. They put a cast on it and I was out for the season.

So I’m on the sofa in our house in the Richard Allen Projects, and my grandfather comes all the way from his house in Germantown on the trolley car. He always would come over to tell me a story and give me 50 cents—the story before the money. He was a very wise man. So this day, he looks down at me and says— well, it’s what he didn’t say. He didn’t say, “I told you so.” He just told me to take care of my shoulder—and I’ve never felt worse, more embarrassed. His mere presence—-

PLAYBOY: What passed between the two of you at that moment?

COSBY: Fifty cents. [Laughs]

PLAYBOY: Getting back to the Huxtables and the Cosbys, do you ever feel you’re the head of two families?

COSBY: Very much so. But I don’t get my children and wife confused with the people I work with. They’re family in the same way Bob Gulp and I were family when we worked on I Spy and still are. The people on The Cosby Show are people I love and care for, and I have things I want for the TV children. But when the day’s over, I don’t have any problems with them. And I know that Phylicia is family in the sense that she could be my younger sister. I have a deep respect and love for her.

PLAYBOY: You had final say on casting The Cosby Show. Why did you choose her to play your wife?

COSBY: Phylicia knew how to look at a kid when you put all the guns on the table and say, “You go upstairs to your room,” and the kid knows that if he doesn’t do it, he’s going to find himself walking on hot coals without his shoes on. Marcy and Dick brought me the three finalists for every role, and Phylicia won flat-out. In dealing with children, some mothers yell and nothing is happening except the sound of a woman yelling. Phylicia was able to say “Case closed” just with her eyes. Lisa Bonet, who plays Denise, was also an obvious winner. Lisa was just what I wanted for Denise—a fashionconscious teenager who’s hip but who appears to be a little off-center and might just decide to become Greta Garbo. She’s not on drugs and isn’t supposed to look like she is, but I wanted Denise Huxtable to seem a little spaced-out, anti Lisa has that quality. Tempestt Bledsoe, who plays 12-year-old Vanessa, was clearly the best in her category. Last year, she was the gossip and the child with the wisecracks. This year, she’s discovering boys, letting her jersey flop off one shoulder and, when not checking herself out in the mirror, is always on the phone.

PLAYBOY: Which was the toughest role to cast?

COSBY: Theo, the son. When the three finalists for the part read for me, the boys all had a similar way of reacting to the parent telling them to do something: They sucked their teeth and rolled their eyes before answering. I said the same thing to all three separately: ‘‘Do you have a father?” “Yes, sir.” “If you said something to your father that way. what do you think would happen to you?” They all gave a sheepish smile and said they’d either wind up going through a wall or doing a crash landing out on the street. So I asked them to talk to me the way they would to their fathers, and we had the three boys go back into the hall. When Malcolm-Jamal Warner came back. I loved what he did. The moves w’ere right; he was talking to his dad. He’s a very Hexible young actor. There was another boy I liked, and I almost asked if I could have two sons. At that point, I knew we were going to have four kids in the house, and I wasn’t too sure I wanted one of them to be a six-year-old girl.

PLAYBOY: Why not?

COSBY: I told Marcy we’d be there shooting for the rest of our lives if we had a little kid. Now, Marcy was the one who wanted the teeny-weeny, and when little Keshia Knight Pulliam came in—I mean, you can’t argue about whether or not she’s a beautiful little girl, because, of course, she is. But I really didn’t think I wanted to work with someone so young. After meeting Keshia, I said, “OK, she’s very, very bright and she’ll be able to handle it.”

Well, now when people talk to me on the street or on airplanes, they all tell me they could just bite that little girl—I mean, Keshia’s more than earned her keep. Getting her was a very smart decision on Marcy’s part, because when you look over the Huxtable family, there’s a kid for just about every age group.

PLAYBOY: Do you feel any pressure about maintaining your top ranking?

COSBY: The pressure in television is to stay in the top 20. You fight to stay alive each week, and you do a lot of hoping. And meanwhile, you’ve got a show to put together and then perform, and en route to doing that, you watch the numbers. It’s almost as if each week, you’re a person looking back to see how you lived. You know, right now, it may look like I’m the boss, but the ratings dictate who’s the boss, and when the numbers drop, you get a visit from the network SS men.

PLAYBOY: Who are those horrible people and what tortures do they inflict?

COSBY: Well, they’re executives who seem to get younger and younger every year, and they say things like, “We think you ought to try doing it our way,” which is not what you want to do. I’ve been there before. If and w hen the rating erosion occurs, you weigh what they say, and if it’s worth anything, you try to comply. This is a very cold business, and if you don’t look at it that way, you can get hurt. For instance, The Jeffersons was on for ten years, and suddenly the network said. “You’ve been on long enough; that’s it.” Well, ten years is a tremendous amount of time to keep a show going on network television, but I think the actors were really upset when CBS let them go.

PLAYBOY: What did you think of The Jeffersons?

COSBY: I felt that it taught most of America about a different kind of sound. The characters’ speech was Southern, and its rhythms were different from what you’d find on I Love Lucy, for instance. But maybe not so different from what you can still hear on The Honeymooners, because Ralph Kramden, even though he wasn’t from the South, was a lower-economic street guy. The Jeffersons got a lot of Americans who watch TV accustomed to that sound, just as Flip Wilson and Redd Foxx had done. Then Richard Pryor came along with The Richard Pryor Show, which didn’t last long—-

PLAYBOY: That’s the one where he said he wanted to appear nude and the network canceled it, right?

COSBY: Yeah, but it had impact. It worked on a sociopolitical level, as well as on an educated street level, which means you could be sitting in the Russian lea Room, having blinis and having graduated from Temple University, and enjoy it right down to your roots.

PLAYBOY: You and Pryor met in the Village when you were both coming up, right?

COSBY: Yeah. He was at the Cafe Wha? and I was at the Gaslight.

PLAYBOY: Why did it take so much longer for him to make it?

COSBY: They wanted only one at a time.

PLAYBOY: And for then, that was you.

COSBY: Well, I came up at a time when Dick Gregory was doing very tough political humor, and I admired him so much I started out doing the same thing. But then I decided I had to break away from that; I felt that if Americans were going to judge people as individuals, you didn’t have to hammer people over the head. So if I played the hungry i in San Francisco and then the Apollo in Harlem, I didn’t go to the Apollo and load up on antiwhite material, nor did I load up on you-black-people-better-get-yourself-together talk. I did the same show at both places and people reacted the same way in both places: They laughed.

PLAYBOY: People often compare your comedy work with Pryor’s and Eddie Murphy’s. What’s most obvious is the difference between their use of profanity and your avoidance of it. I las that been a calculated decision on your part?

COSBY: No, it’s just that I’ve never been comfortable with profanity. During the early Seventies, there was a time when I used profanity on stage for about six months. I was trying to get the audience to understand the language between a father and a son, and it involved a lot of cursing. I did a bit that showed my father cursing me and I found that the audience . . . just was not ready for me to curse on stage. So I cut it out, and I had to find another way of doing that piece without using curse words.

Now, I happen to think that Richard’s way of using four-letter words and 12-letter curse words has nothing to do with Eddie Murphy’s way of using 77-letter curse words.

PLAYBOY: So you don’t find Pryor’s humor offensive?

COSBY: Richard to me is like Lenny Bruce, and I think a lot of what he does and says is to try to get people to understand different kinds of behavior. Richard has also developed some characters that I absolutely admire, such as Mudbone and the wino in a crap game— I’ve known those people. I’ve seen them, I grew up around them and they were wonderful. Those are not embarrassing characters. Pryor also has a brilliant study of a man getting drunk and coming home and wanting to punch out his wife but being too loaded to do anything but pass out. All of these things are pertinent to human behavior.

Now, I wish I could explain Richard when it came to physically abusing himself, but I can’t, because I don’t know behaviorally where Richard is or was then.

PLAYBOY: You seem ambivalent in your feelings toward Eddie Murphy. What do you think of the choices he’s made thus far?

COSBY: Listen, Eddie Murphy is a young man who is extremely, extremely intelligent. In terms of performing and self-editing, Eddie Murphy has made a choice. He knows what’s right, he knows what’s wrong, he knows what will upset people and what will not upset people. He has decided he’ll say what he wants to say, and if it upsets some people, fine—but he’s going to say it, anyway. Now, I don’t happen to think of Eddie as a stand-up comedian. One of the reasons there are only a few stand-up comedians, like Billy Crystal and Jay Leno, around is that when somebody gets hot, they go into movies—and Eddie Murphy packs people into theaters. The question, perhaps, then comes down to this: Is Eddie Murphy, with his street language, harmful?

When Murphy broke into movies in 48 Hrs., I agreed with Pauline Kael of The New Yorker, who raved about the young man. I did not agree with the total about-face she did on Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop. Same fellow, right?

PLAYBOY: How did you feel when Murphy impersonated you on Saturday Night Live as a kind of pompous, cigar-waving Bob Hope figure?

COSBY: I didn’t mind it. I think there are always these positions younger people take, coming into a field, looking at older people and thinking, Hey, you’re not that good; I can be better. That’s how you get pupils to surpass their teachers.

PLAYBOY: So, overall, you like Murphy’s brand of humor.

COSBY: I like his movies—his movies. They make me laugh. They make a lot of people laugh. That’s not an easy thing to do, which is why I have a problem with the entire entertainment industry and its rejection of comedians. People in the industry will admit that comedy is a tough business. They will also admit that you have to be very intelligent to be able to get people to laugh. Well, if we weigh and measure the importance of making an audience laugh and the good feeling people get from that, why does the record industry always make sure it won’t even announce who won best comedy album on the Grammy telecast? And I think it’s just flat-out dumb for the movie industry not to nominate funny actors like Steve Martin for Academy Awards. Academy Award nominations almost always go to actors who are deeply serious and who are in serious movies. Of course, a lot of those movies are funny anyway.

PLAYBOY: Are you grousing because you’ve made ten movies and have yet to be nominated for an Academy Award?

COSBY: Absolutely, absolutely not! Whatever chance I ever had to be nominated was when I was part of the big cast— Maggie Smith, Michael Caine, Alan Alda, Jane Fonda, Richard Pryor and me—in California Suite. The producer of that movie, Ray Stark, called me and told me he was taking out ads and trying to get everybody nominated, and I told him I wasn’t interested. It’s very difficult to tell producers that.

PLAYBOY: Why did you?

COSBY: For the same reason I told the Emmy people that I didn’t want to be nominated for The Cosby Show: I remember the years with Bob Culp on I Spy, being up against my buddy and hoping that I’d be the one chosen . . . for what? Well, because it’s the highest award you can get from the television academy. OK, I won Emmys three years running, and then I started hoping my television specials would be chosen for an Emmy over somebody else’s television specials. But I wasn’t making television specials in hopes that mine would be chosen over somebody else’s. I’m not doing this situation comedy in order to compete with Bob Newhart and Robert Guillaume.

As far as that possible Academy Award nomination, hey, I knew that Ray Stark was talking to me about money, because if you’re just nominated—you don’t have to win—you’ll be more in demand and you’ll be offered more money the next picture you act in. Meanwhile, I have to tell you my performance in California Suite was not very good. I really didn’t understand about a third of what I was doing in that movie.

PLAYBOY: What was the problem?

COSBY: Doc [Neil] Simon’s lines don’t knock me out; but then again. I’m not an actor, I’m a stand-up comedian. I like a flow from one line to another, and I just couldn’t make the connections between Simon’s lines. That had nothing to do with Doc’s being white and Jewish. It just had to do with me—and Pryor, too, I think—not being a trained actor. If they’d done our segment with black actors like James Karl Jones, Cleavon Little, Clarence Williams III or Al Freeman, Jr.—fellas who know their way around Chekhov and Ibsen and who also know their way around the complexities of a character—well, the thing would have come off better. But I still enjoyed working with Richard and I enjoyed the physical parts of our piece—the fight and the tennis match.

PLAYBOY: Despite your successful collaboration with Sidney Poitier in Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again and A Piece of the Action, movies have never really been your medium. Has that been a source of disappointment?

COSBY: No, because I never cared about being a movie star. To me, that was a gimme—you want to give it to me, fine, I’ll take it. That’s not to say we don’t all have fantasies about becoming movie stars: “Oh. I’m so glad you liked my last film. Yes, right now my agent’s sifting through a pile of offers. Of course I know that Marlon wants to work with me, but I won’t even consider it unless we find the right director.” In reality, the TV series is exactly w hat I enjoy doing.

PLAYBOY: You also once said that jazz was an important part of your life and that you learned a lot about comedy by watching jazz musicians perform. Still true?

COSBY: Yeah. I started consciously listening to jazz and loving it when I was 11 years old and bought my first pair of drumsticks. I’m a self-taught drummer, and sometimes, friends of mine like Dizzy Gillespie and Jimmy Smith will let me sit in with them. They do that as a favor to me, because it’s no great thrill for them to have this incompetent up there with them—if I was really their friend, I’d stay in the audience, where I belong. Anyway, in the Fifties, Philadelphia had a lot of small jazz clubs, and when I was 16, I’d go listen to musicians like Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Charlie Mingus and Bud Powell. I once heard a jazz band play The Joint Is Jumping and Cottontail and then discovered that those two songs are really versions of I Got Rhythm. So I began listening more and more to the piano players and bass players going through intricate chord changes, and I’d also watch the next soloist thinking about what he was going to play when it was his turn. When I started doing comedy, I began structuring my work the same way jazz musicians do; to me, a joke is a tune that has a beginning, a middle and an end. I’m the soloist, and my chord changes are the punch lines that make people laugh.

PLAYBOY: Can you play a little for us?

COSBY: Sure. Here’s a very simple joke: You walk into a room to get something, and when you get there, you forgot why you came in. You stand there trying to remember what you were looking for, and then you leave the room. Now, that’s all there is to this particular tune. I start out very simply, but en route to the room or standing in it or coming out of it, I can play any chord change I want—as long as it’s funny. I can go into the room, look around and have no idea what I’m looking for, and then one of my kids will come in and say, “Gee, Dad. did you forget what you were looking for again? Boy, your mind’s really going.” That’s one chord change, or I can talk to myself and say something like, “I’ll recognize what I’m looking for when I see it.” I may follow that up with another chord change: “Well, how do I know I’ll recognize what I’m looking for when I see it?” I can play that tune any way I want to, which is how a jazz musician works.

PLAYBOY: You’re also now writing a book about how to be a father. Do you consider yourself an expert on raising children?

COSBY: Ask me anything, I’ve got the answer. You know, when I first became a parent, I had certain ideas about how I was going to control the children, and they all boiled down to this: Children just need love. Well, some years later, you find yourself talking to your child, who is of high intelligence, and saying, “No, you cannot drive the car until you get a learner’s permit.” And then, ten minutes later, you see your car being driven down the street by the same child you just told not to drive it. When the child gets back and gets out of the car, you have the following conversation: “Was that you driving the car?” “Yes.” Why?” “Well, I just wanted to see if I could do it.’ “But didn’t I tell you not to drive it?” “Yes.” “Well, if I told you not to drive the car, why were you driving it?” “I don’t know.” Well, to me, that’s brain damage. All children have that kind of brain damage. Parents should prepare themselves to face that fact.

PLAYBOY: Is there anything you can do about it?

COSBY: Not much. Which is why you wind up doing a lot of yelling. There have been times when I’ve felt like a football coach in the locker room at half time, and here we are, 16 points down against a team we’re favored to beat by three touchdowns. And there I am, saying to this team, “Listen, if we win this game, we can go to the Super Bowl!” And I’m looking at a team that just won’t wake up. though I know what they can do if they start to play. So now I’m kicking the benches, because I realize I might as well be talking to the walls, and I probably am.

If you’re a father, you get to be very familiar with that situation. I don’t know how many times I wanted one of the kids to go in a certain direction and the child wanted to go in another direction that I knew was no good for the kid, so I gave maybe my 55th reading on why the child should go in the direction I was pointing to. And there I am, putting in love, investing in presents, resorting to outright bribery in the form of cold cash and even invoking racial pride. I mean, I’m telling my daughter that black America is waiting for her, that she cannot disappoint Harriet Tubman—I’m giving it my best shot. And when I’m finally done, my little girl turns to me and says, “Gee, Dad, I don’t think I want to do that.”

PLAYBOY: Have you ever lost your temper and physically lashed out at your children?

COSBY: I was physical with my son just once, very physical, but not because I lost my temper. I just didn’t see any other way of getting him to make a change, so along with being physical with him, I begged him to understand that I truly, truly loved him and that he had to understand that what I’d asked him to do was best for him. And I really wouldn’t— and didn’t—leave until he understood that. I stayed and poured out what was in my heart until he accepted the fact that I did the physical thing because I finally didn’t sec where talking to him had done any good. And that I meant for him to do exactly what I said and that I wanted him to understand he had no choice in this particular matter. And my son made a change.

Now, I don’t want anyone to think I’m advocating physical punishment, because that doesn’t always work, either. When I was a kid, I don’t know how-many beatings I got for different things. It was still a matter of my priorities versus those of my parents and what I thought I could get away with.

PLAYBOY: Have you run into situations where, as your children have gotten older, there’s simply no dissuading them from a course of action you oppose?

COSBY: Yes, that’s happened. We live in an academic environment, and Camille and I feel that formal education is the best way to go for our kids, but one of our children—who’s entitled to privacy on this—has told us, “I really don’t want to learn the technical aspects of any thing; I just want to be out on my own.’ Obviously, this child has a better idea. So we let the child go. No one’s getting kicked out of the house, and we’re not pulling away the safety net. We have phone numbers, and the person is to call any time there’s any trouble. But we’re also saying, “This is your idea, and you’re going to have to earn the right to be on your own. You get no money from us toward your support.” In other words, the kid’s really out there. It’s not one of those things where the parents say, “OK, go do it,” and then they get a call and the child says, “Gee, folks, I’ve got this phone bill to pay and I need a car.” We re telling this child, “You have to function on your own if you want to live the lifestyle you’ve chosen for yourself.”

All our children have met a lot of black Americans who have succeeded, who have achieved and who are highly educated. The choice this child has made seems to be, “Listen, there’s a lot of fun to be had out there.” And it’s disheartening. However, when I look at my own life and some of the choices I made when I w as young—you just never know.

PLAYBOY: Do you think you may be too demanding, expecting perfection from others?

COSBY: Oh, I know that everything’s not perfect. I mean, I see how’ people love the Huxtable television family, and then I turn around and look at South Africa and hear my Government saying, “Well, we’ve got to take it easy,” and I know everything’s not perfect. Io have a man like Jerry Falwell invoking the name of Jesus and talking about spending $1,000,000 to strengthen South Africa’s segregationist government—believe me,

I know everything’s far from perfect.

PLAYBOY: How do you feel about U.S. policy toward South Africa?

COSBY: I’m actually embarrassed as an American that our Government—the one that’s in office now—has done so little to change the situation there. Can’t w e be enough of a big brother to South Africa to take our younger brother very gently around the shoulders and say, “How do you feel?” Not necessarily “Little brother, you’re wrong,” but at least say, “ Lake a look at us. Democracy isn’t as bad as you think.” Instead, we go over and dance with that brother and we give a clear message to the world that the United States is pro-apartheid. I was shocked that a representative of the Reagan Administration went on TV to chastise Bishop Tutu for not attending a meeting with President Botha, who had basically said, “I don’t care what anybody else says or thinks, apartheid will remain the law of this land—but you can come to my meeting, Bishop Tutu.” Once again, we got my Uncle Jack working. And what isn’t he going to give the black people of South Africa? Look at America’s doctrine of democracy, and then read what the South African government says an individual can and cannot say and where black South Africans can and cannot live, and then read about how people who oppose the government—who simply disagree with it—are imprisoned. If black South Africans want democracy, Uncle Jack will be glad to tell them why he has decided not to give it to them—it’s because they had the nerve to ask for it.

PLAYBOY: What would you like President Reagan to do about South Africa?

COSBY: Why hasn’t he seen to it that somebody in the Government has stood up and said, “The Reagan Administration believes that this apartheid, this killing, is wrong, and you’ve got to clean up your act”? I am waiting for somebody in the Government of the United States of America, the land of opportunity, to say to its little brother South Africa, “You gotta stop this. Period. Forget that you’re making us look bad—morally, you have to stop this!”

PLAYBOY: What do you believe is going to happen in South Africa?

COSBY: I think that in our first Interview, I made a statement about the U.S. in which I said that black Americans would never again sit still for segregation or discrimination. And now, in 1985, my statement is that black South Africans have reached that same moment in time. If the white South African government decides to kill and go to war, there will be a war. But that government will not be able to hold on to the country without a war. Too many black South Africans are now saying, “If I have to live as a third-class citizen under the rule of apartheid, if this is to be my life, then I don’t want to live.” There’s no turning back for the blacks of South Africa. Now, I ‘m not saying or thinking that South African blacks are going to slaughter South African whites and run them all out of the country and then say, “This is our land.” I’m only telling you that those people will no longer tolerate apartheid. All they want is to live like human beings.

PLAYBOY: When you spoke about race relations in the U.S. 16 years ago, you were very pessimistic about the future. What are your feelings about the subject today?

COSBY: The same, and it isn’t just blacks and whites—it’s about what’s happening among all people in the U.S. More and more in this country, we re not able to say the word American for everybody who lives here. Even the movie industry—maybe especially the movie industry—commits almost blatant crimes with some of the films it puts out. In Year of the Dragon, one white man walks into Chinatown and decimates the place. This again reminds everybody who’s nonwhite that he can be mistreated—and we’re still talking about Americans. For God’s sake, if you grew up when I did and you were black, when you went to the movies and saw Tarzan, you were told that you could just drop a white baby out of a plane and by the time he was 16, he’d be running the entire jungle. This year, if you’re black, you can go see a cult film popular with kids—and tine of the dumbest pictures ever made—The Gods Must Be Crazy, which shows that if you just drop a Coke bottle out of an airplane, you can pretty much shake up an entire African culture. [Laughs sarcastically] Black people certainly are primitive, aren’t they? If you want proof, send in a white film maker.

PLAYBOY: Let’s close on your career. With everything going so well for you, why have some reporters written that this latest burst of success has made you difficult, arrogant? What’s that all about?

COSBY: It’s all about when I say no. It’s all about how I look at someone when he knows he’s said something dumb and I won’t help him out of the hole. It’s not that I pile the dirt on top of him and smash the shovel down, but I guess I let people know when I think a question or a statement is rude or dumb or whatever. A woman from TV Guide recently interviews me and wants to do amateur psychoanalysis. A photographer from the Los Angeles Times poses me this way and that way for what seems like an hour, and I finally tell her I think I’ve done what she wants. They’re going to tell people I was arrogant.

PLAYBOY: How do you feel when you’re accused of not being outspoken enough in your show on matters of race and politics?

COSBY: It depends on the person making the attack. If it’s just some neoliberal who feels I should be a martyr—you know, the kind who says I should take my show, tell everything like it really is and get canceled in three weeks—that person has no idea what life is all about. And neoliberals have a great deal of racism in their hearts. Why else would they tell you to go out and get your brains blown out?

PLAYBOY: Who are these neoliberals— members of the press?

COSBY: That’s what I’m talking about, the press.

PLAYBOY: Still, you’ve gotten a lot of very good press lately, most of it centered on the way you’ve become almost a national father figure—which means that the media will continue to ask you a lot of daddy questions. Do you have any parting advice on that topic?

COSBY: I’m doing a book on being a father. It’ll be out around Father’s Day.

PLAYBOY: You’ve already discussed the subject with us, and the book wouldn’t preclude some remarks from you on the subject, would it?

COSBY: It might. The publishers have paid me an awful lot of money. And since this is only one brain I’ve got. . . .

PLAYBOY: Come on. Bill. This is the Playboy Interview—some of our readers are fathers, and even more are moving into that time of life.

COSBY: Yeah, I think that the subjects we’ve talked about ate interesting—especially for Playboy—because what you have here is a guy saying that he’s given all of himself to his wife and children. I think that may turn some lights on.

PLAYBOY: So we’ll press you: What’s your parting advice to people who’ll soon be parents?

COSBY: Well, I speak to my son and daughters about heroes, people whom we look up to for various reasons. What is it we worship about a person? What is it that makes that person a hero to you? And if it is that the person is perfect, then you really haven’t done an honest job on yourself, because people are not perfect. Edwin Moses is a great track star who this year was arrested for possession of marijuana and soliciting a prostitute. The TV networks picked up on it. and then came all these discussions about “What are our heroes coming to?” Now. I felt sorry for Edwin, but then I also felt. Well, if it’s true, am I going to be angry with him and not think that he is a great athlete anymore? I told my children what Edwin was charged with, and I said, “I still want you to look at Edwin Moses as a hero.” They said, “Well, Dad, how can we after he’s done this?” I said, “Even if he’s found guilty, are we going to trash what this man has done, which is to win 109 races in a row-?’’ We became fans because he’s a man who worked eight to ten hours a day, punishing himself to get in shape to achieve his dream. We all said, “What a great athlete; what a great man dedicated to achieving his potential.” That’s what we can say about Edwin Moses. We’ve got to examine who and what a hero is and how far we, the fans, go in putting these people up on pedestals. They’re not perfect, but then again, neither are we.

Source: Playboy, December 1985