A Galactic Renaissance: ‘Dune’s’ Vital Role in Shaping Modern Sci-Fi Narratives

Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ captivates new readers with its epic narrative and profound themes, redefining science fiction with every turn of the page.

Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ captivates new readers with its epic narrative and profound themes, redefining science fiction with every turn of the page.

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Richard Church, himself a novelist and poet who had fought in World War I, believed that Erich Maria Remarque’s remarkable little novel allowed the reader to truly understand the horrifying and brutalizing experience of those who fought in the Great War

Sir Herbert Read was a British art historian, poet, and critic. His book of poetry, Naked Warriors (1919), reflected his own experiences in World War I. In the following viewpoint, written as a review of a half-dozen war books, he discusses why, ten years after the end of the war, people had so much interest in war literature.

When Remarque’s English publisher sent an advance copy of the novel to Sir Ian Hamilton, a British general, Hamilton wrote a letter to the publisher thanking him and telling him how true he felt the book was and how deeply it had touched him. The publisher forwarded the letter to Remarque, who responded with the letter below.

Nati dalla fantasia degli scrittori e fatti vivere nelle pagine di un libro, certi personaggi della letteratura hanno un destino singolare: col passar del tempo assurgono all’altezza di caratteri universali e, tralasciata del tutto la loro matrice artistica, cominciano a vivere una vita propria e imbarazzantemente perenne, fino ad entrare nel linguaggio di tutti i giorni.

We played a fateful role in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s life. An epitome of his philosophy, the novel prefigured his own future and that of his country with astonishing accuracy.

A gripping suspense tale, The Handmaid’s Tale is an allegory of what results from a politics based on misogyny, racism, and anti-Semitism. What makes the novel so terrifying is that Gilead both is and is not the world we know.

In this essay, Ketterer examines the cyclical structure and historical perspective of The Handmaid’s Tale. According to Ketterer, Atwood breaks from traditional dystopia conventions by juxtaposing present and post-dystopia contexts.

As Ronald Gottesman points out in this discerning introduction, Upton Sinclair was a passionate believer in the redemption of mankind through social reform. His expose of the interlocking corruption in American corporate and political life was a major literary event when it was published in 1906, and caused an almost immediate reform in pure-food legislation.

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Richard Adams analyzes the title and opening paragraphs of Heart of Darkness, showing that neither gives the reader clues regarding the subject matter and focus of the story.

Canadian Author Margaret Atwood’s sixth novel will remind most readers of Nineteen Eighty-Four. That can hardly be helped. Any new fictional account of how things might go horribly wrong risks comparisons either with George Orwell’s classic or with Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

Il Rosso di Jack London Eccola di nuovo! Quell’improvvisa esplosione di suono, mentre ne calcolava la durata sull’orologio, Bassett la paragonò alla tromba di un

One of the more diverting aspects of Lolita, the most controversial best seller of the century, has been the considerable speculative curiosity about the private life and personality of Vladimir Nabokov, the virtually unknown university professor who now, at the age of sixty-one, finds himself world famous as the author of this nettlesome novel.

A couple, whose careers (tennis player and actress) depend on youth, are forced to deal with a gift of a single dose of rejuvenating medicine that cannot be divided or shared. This story was the basis for The Fountain of Youth, a 1956 TV pilot for a proposed anthology series, produced by Desilu and written, directed, and hosted by Orson Welles.

In the following review, Tom O’Brien cites flaws in the plausibility of Atwood’s dystopia as depicted in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Having soothed themselves with these comfortable falsehoods, people proceeded on their way to make Orwell’s prognostications come true. Bit by bit, and step by step, the world has been marching toward the realization of Orwell’s nightmares; but because the march has been gradual, people have not realized how far it has taken them on this fatal road.

Hemingway managed to catch and hold in his novel a set of attitudes toward war and human love which are essentially ageless. Moreover, the prose style in which he says his say about the people he knew in that now-ancient war has remained for the most part singularly invulnerable to the assaults of time.

by Joan London Of all Jack London’s serious works, none has been more widely misapprehended than Martin Eden, which he began to write soon after

Robert Hass, in his introduction to the Bantam edition of “Martin Eden”, points out that Jack London simply reflects the culture of his time, a culture that was dominated by imperialism, social Darwinism, and a style of aggressive masculinity.

In the following essay, published in 1970, Spinner discusses the autobiographical novel Martin Eden, which he regards as one of the first bleakly existentialist anti-hero novels in American literature.

Joseph Needham, one of the leading biologists of his day, strongly proclaims that Huxley has gotten the science—biology and psychology as well as philosophy—exactly right. Brave New World clearly shows what lies ahead, and it should be required reading especially for those who trust in science to save the world.

Huxley’s preoccupation with and concern about the increasing prosperity and numbers of the proletariat found expression in Brave New World. Huxley felt the masses had grown more menacing with population increases and he wrote the novel at a time when it seemed mankind could not recover from the problems of war, depression, and explosive technological progress.

by Sam S. Baskett The poem of the mind in the act of finding What will suffice. —“Of Modern Poetry,” Wallace Stevens When Martin Eden

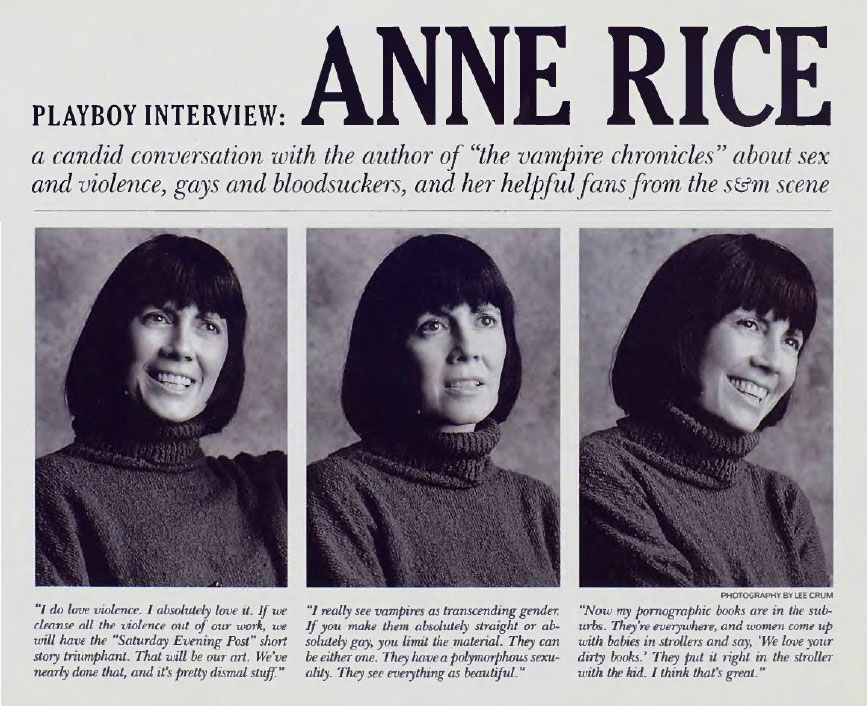

A candid conversation with the author of The Vampire Chronicles about sex and violence, gays and bloodsuckers, and her helpful fans from the S&M scene

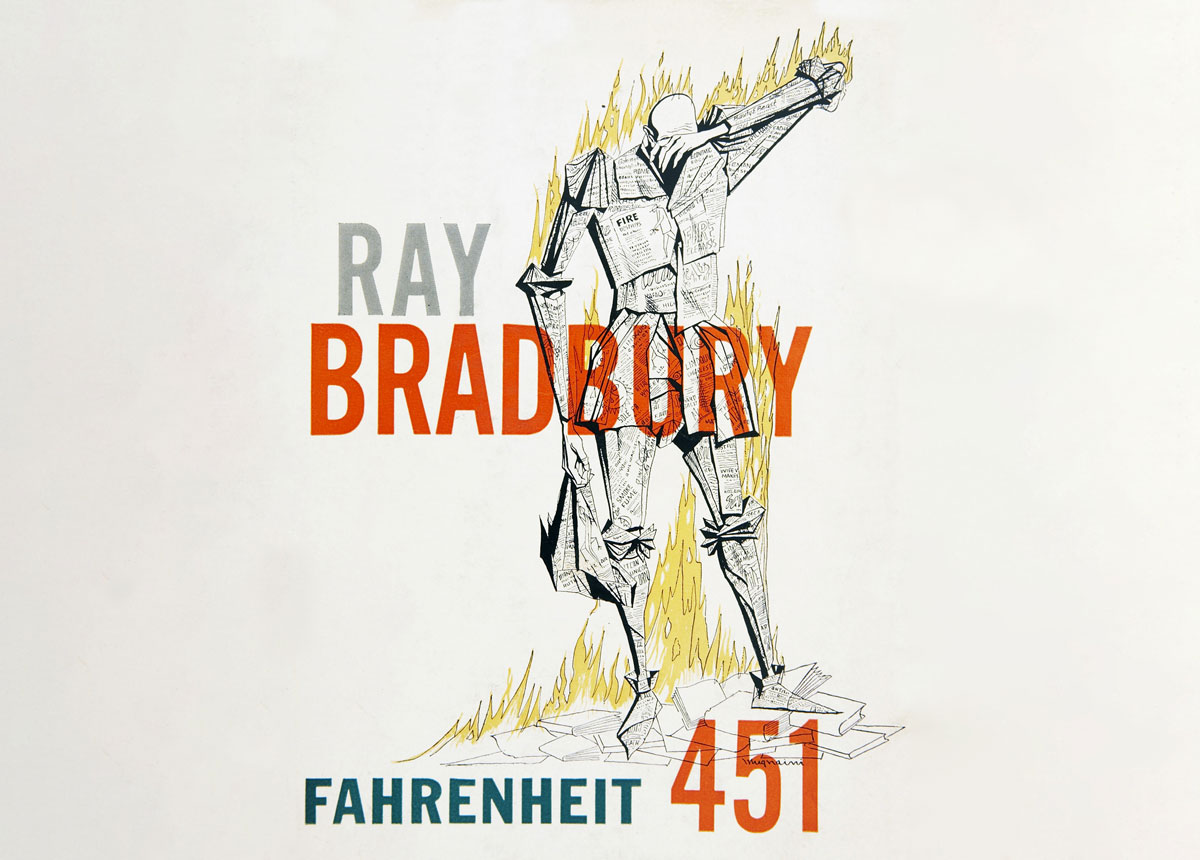

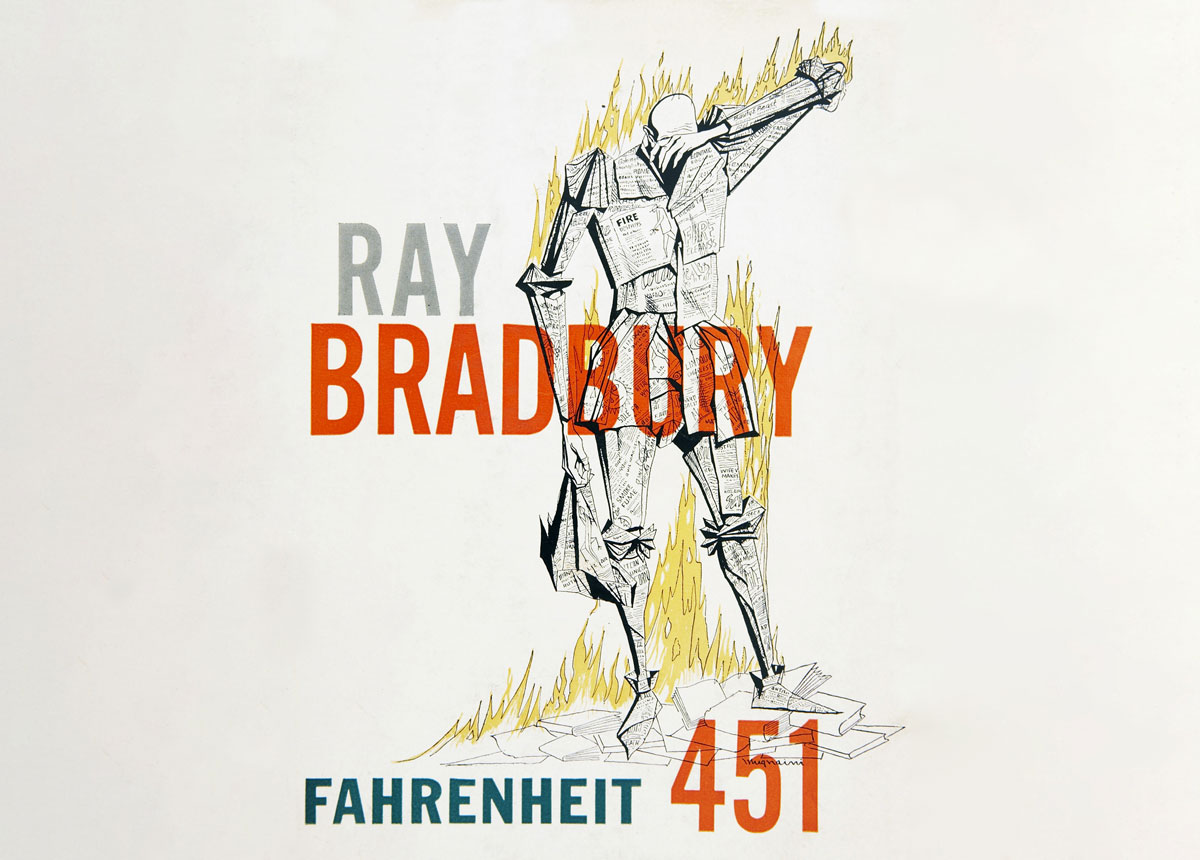

Book burning and repression of thought and ideas are far from the only themes in Fahrenheit 451. The novel comments on many other aspects of modern life that Bradbury deplores, and it is a striking vindication of his vision that many of the aspects of modern life he deplored at that time are even more pronounced today.

Henry Sugar, a wealthy man, decides to take on an extraordinary challenge – he wants to master an extraordinary skill in order to cheat at gambling games.

The novel opens with “fireman” Guy Montag exulting in his job of burning books: “It was a pleasure to burn.” In his futuristic society, where

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!