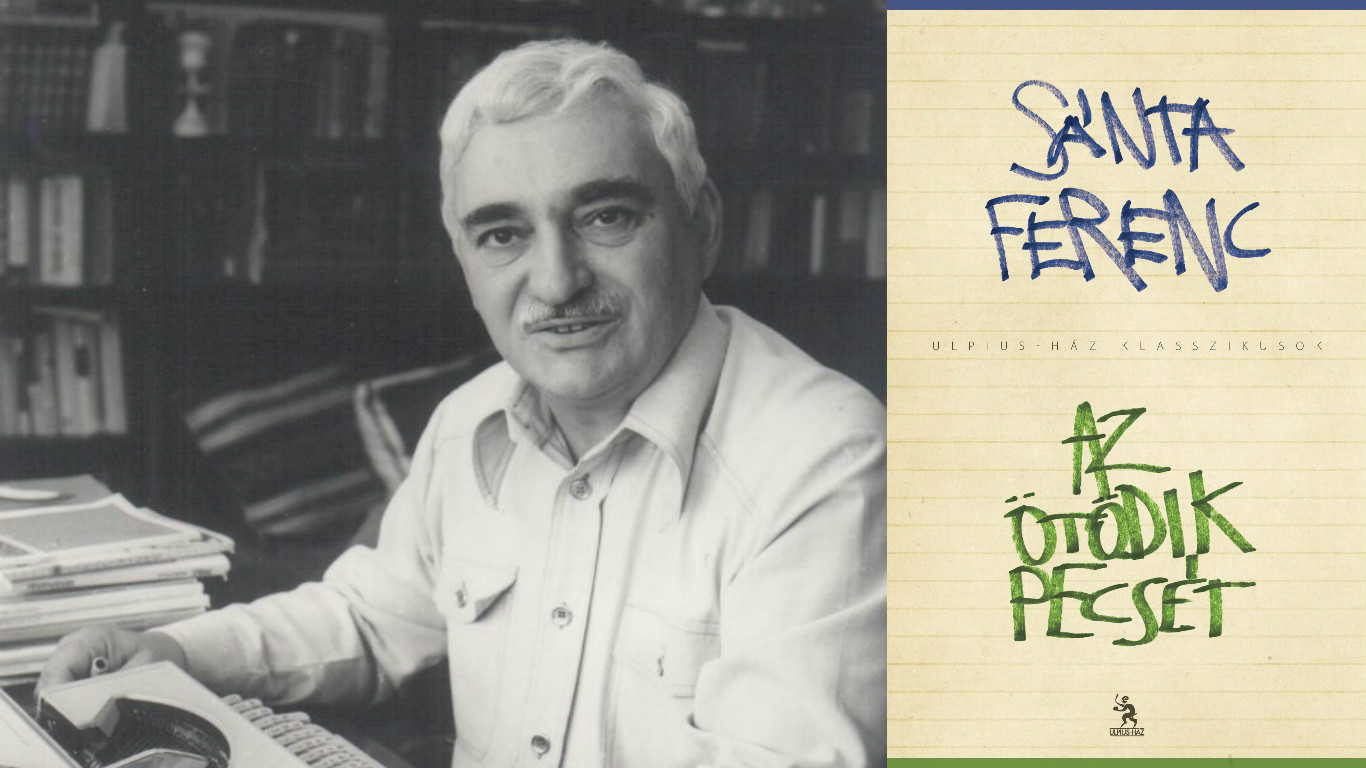

Apart from the works devoted to descriptions of life in the camps by Erno Szep and Istvan Orkeny, Hungarian writers began to treat the theme of World War II during the 1960s. Ferenc Sánta’s novel Az otodik pecsét (The Fifth Seal; 1963) thematizes individual moral responsibility during a war

The events of Az ötödik pecsét take place in Budapest and show the daily life of ordinary citizens during the reign of terror unleashed by the Arrow Cross Party, the Hungarian Nazis, in the autumn of 1944. In those days, no one was safe. Three artisans, a book salesman, a carpenter, and a watchmaker meet with Béla, keeper of a tavern, to drink wine and chat. The four are not close friends, but they know and trust each other. A newcomer appears, a photographer and former soldier who lost a leg on the Eastern front. The watchmaker is “a cross-grained sort of chap” who likes to provoke and challenge people. In the middle of a long discussion about the preparation of a breast of veal, the watchmaker tells his companions a parable about a tyrant and his slave, asking them to choose between the happy life of an immoral despot and the life of an innocent slave, full of sorrow, humiliation, and suffering. The men take this seriously and start a long discussion about human nature. The soldier-photographer prefers being an innocent slave, but the watchmaker calls him a liar. Before the curfew, two Arrow Cross men come into the tavern and intimidate the group. When they are gone, the artisans talk about their disapproval of the new political regime. The narrator takes the opportunity of their departure to present each of them separately and in great detail.

The unexpected turn comes with the revelation that the argumentative watchmaker has turned his home into a refuge for eight Jewish children. He spends the evenings and nights cooking and cleaning, as well as with correcting the childrens homework, and consoling them. The photographer goes home humiliated, for he is hurt that his partners did not believe that he would prefer to be an innocent slave. He decides to take his revenge by denouncing them to the police. The following evening all four men are taken by the police for questioning, and they are forced to choose between their lives and their dignity.

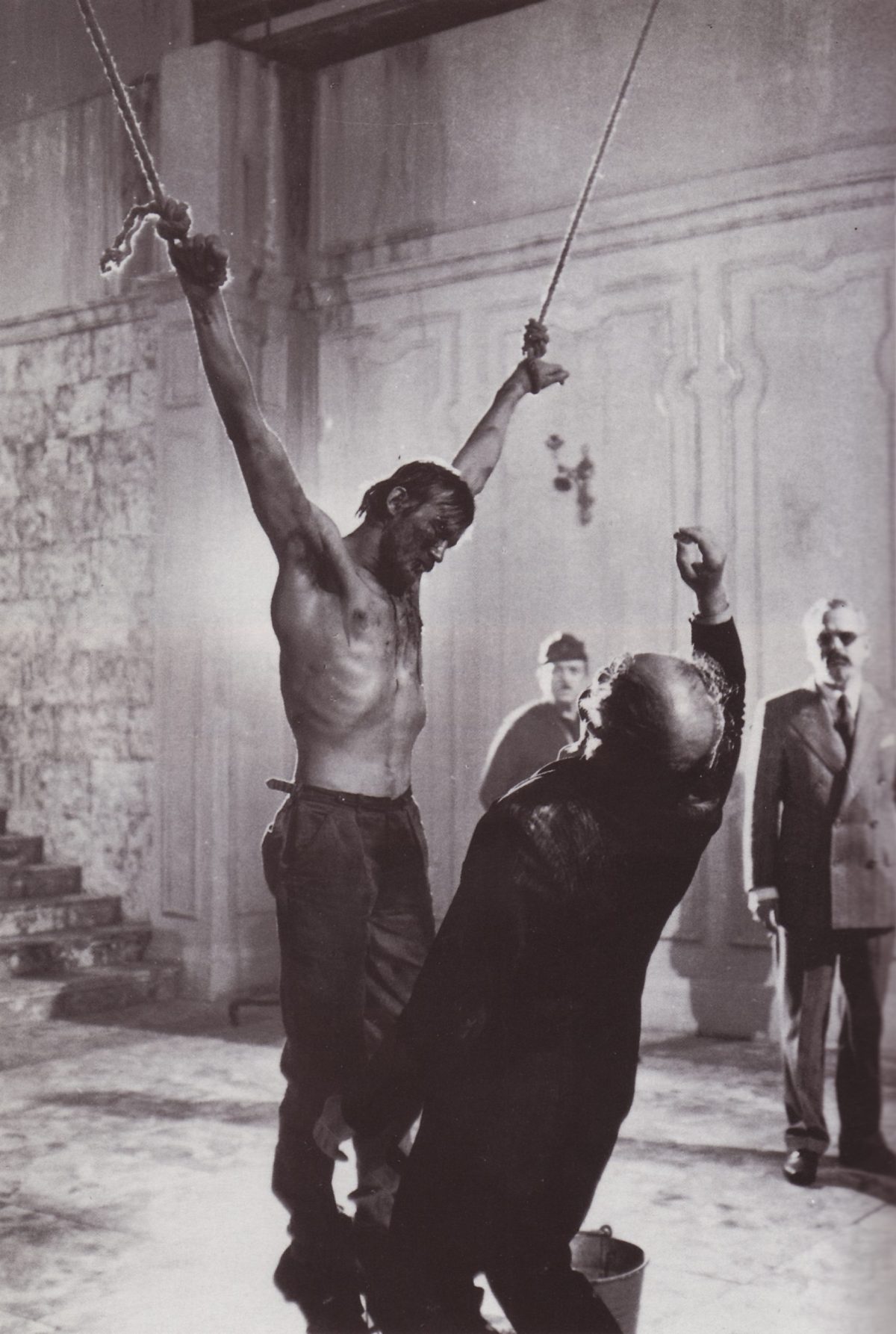

These dramatic events, tragic choices, and heroic attitudes are told in a realistic prose, but the narrator’s voice and the dialogue style vary from colloquial to elevated. Showing the quotidian of these four characters, the narrator offers excessively long portraits that take up more than half of the novel. The second half takes a dramatic turn with the interrogation of the four men. Their theoretical discussion about moral choice and individual responsibility now undergoes a test in confrontation with brutal violence. The tension reaches its climax when the young officer offers the prisoners a choice: either to beat a tortured prisoner, in which case they will be released, or to be killed.

The prisoners look one by one at the man who is hanging with his arms tied behind his back from a long rope “running from a pulley fastened to the ceiling, so that only his toes touched the floor” (Fifth Seal 179). The horror, hesitation, and inner struggle of each alternates with descriptions of the victim’s suffering. Sánta’s predilection for detail supports here the meaning: approaching the tortured man, each prisoner witnesses his agony but registers a different aspect of his suffering. The watchmaker finally approaches the dying man and hits him, despite protests from the book salesman, who does not know what the reader knows, namely that the watchmaker must go home to protect the Jewish children. The novel suggests that ordinary people can turn into heroes under extreme circumstances.

History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe. Volume IV: Types and stereotypes, edited by Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer, pp. 497-498