by Penelope Gilliatt

“When you take a fall,” the ailing Buster Keaton explains to me from the top of a bookcase as he is nearing seventy, proceeding then to zoom towards the window, “you use your head as the joystick.” The poetic human airship grounds delicately, and coughs.

He often seems to see himself rather distantly and as if he were some mechanical object. I suppose this is partly because of the physicality of a stage career that began in vaudeville as a manhandled toddler called “The Human Mop,” and partly because he has an exceptionally modest notion of himself, including his suffering. Hollywood after the talkies treated the decorous genius like a goat.

“You don’t go out of your way not to talk in a silent film,” he says, “but you only talk if it’s necessary.” Two-minute pause. He is sitting in his rather poor ranch house in the San Fernando Valley, quite a drive from the stars’ hangout in Beverly Hills. He always talks about work done long ago in the present tense. You wouldn’t use any other.

He has been less canny than Chaplin or Harold Lloyd about retaining possession of his pictures and preserving himself from the new producers, and after the halcyon time his working conditions were ruthlessly taken from him, followed by the sack from Louis B. Mayer and the boot from a chilling wife, who changed their son’s surname when the gloss went off it. But with his back to the wall and drinking enough to kill himself he still seems to have been practical and even rather dashing, with much the same spirit as his fighting Irish father, who once dealt with an impresario’s humiliating order to cut eight minutes out of the family vaudeville act by setting an alarm clock to go off on stage in the middle of the routine. It seems entirely characteristic of Buster that he should once have escaped from a straitjacket during the anguish of DTs by a music-hall trick learned from Houdini. As an infant he was plucked out of the window of his parents’ digs by the eye of a cyclone, and deposited intact a street away. Maybe it was this incident that planted in his father’s head the theatrical possibilities of throwing the baby around. Joe Keaton started by hurling him through the scenery and dropping him onto the bass drum. When the child bounced, he began wiping the floor with him. One of his costumes had a suitcase handle on the back of the jacket so that he could be swung into the wings. Joe Keaton’s wife, Myra, a lady saxophonist who seems always to have been at the end of her tether, used to refer thinly to the human-mop rehearsals as “Buster’s story hour.”

Buster is now sitting down, his back away from the back of the chair. The pause goes on. He is trying to explain, on the basis of what he started learning this way in vaudeville when he was rising three, the machinery of silent jokes. The beautiful head looks out of the back window, on to the plot of land where he has built his hens a henhouse that has the space of an aviary and the architecture of a New England schoolhouse. The great master of comedy, who is one of the true masters of cinema, suddenly gets up again and climbs onto a dresser and does a very neat fall, turning over onto his hands and pretending that he has a sore right thumb. He keeps it raised, and then stands stock-still and looks at it, acting. “Suppose I’m a carpenter’s apprentice,” he says after a while. Chest out, manly look, like a Victorian boy with his hands in his pockets having his photograph taken. “Suppose the carpenter hits my thumb with his hammer. Suppose I think, God damn, and leap out the window. Well, I’m not going to say my thumb hurts, am I? That’s the trouble with the talkies.”

He sits down in his chair again and thinks. He is wearing a jersey with piratical insignia on the front, and the sort of jaunty trousers that people sported on smart yachts in the 1930s. “The thing is not to be ridiculous. The one mistake the Marx Brothers ever make is that they’re sometimes ridiculous. Sometimes we’re in the middle of building a gag that turns out to be ridiculous. So, well, we have to think of something else. Sit it out. The cameras are our own, aren’t they? We never hire our cameras. And we’ve got a start, and we’ve got a finish, because we don’t begin on a film if we haven’t, so all we’ve got to get now is the middle.”

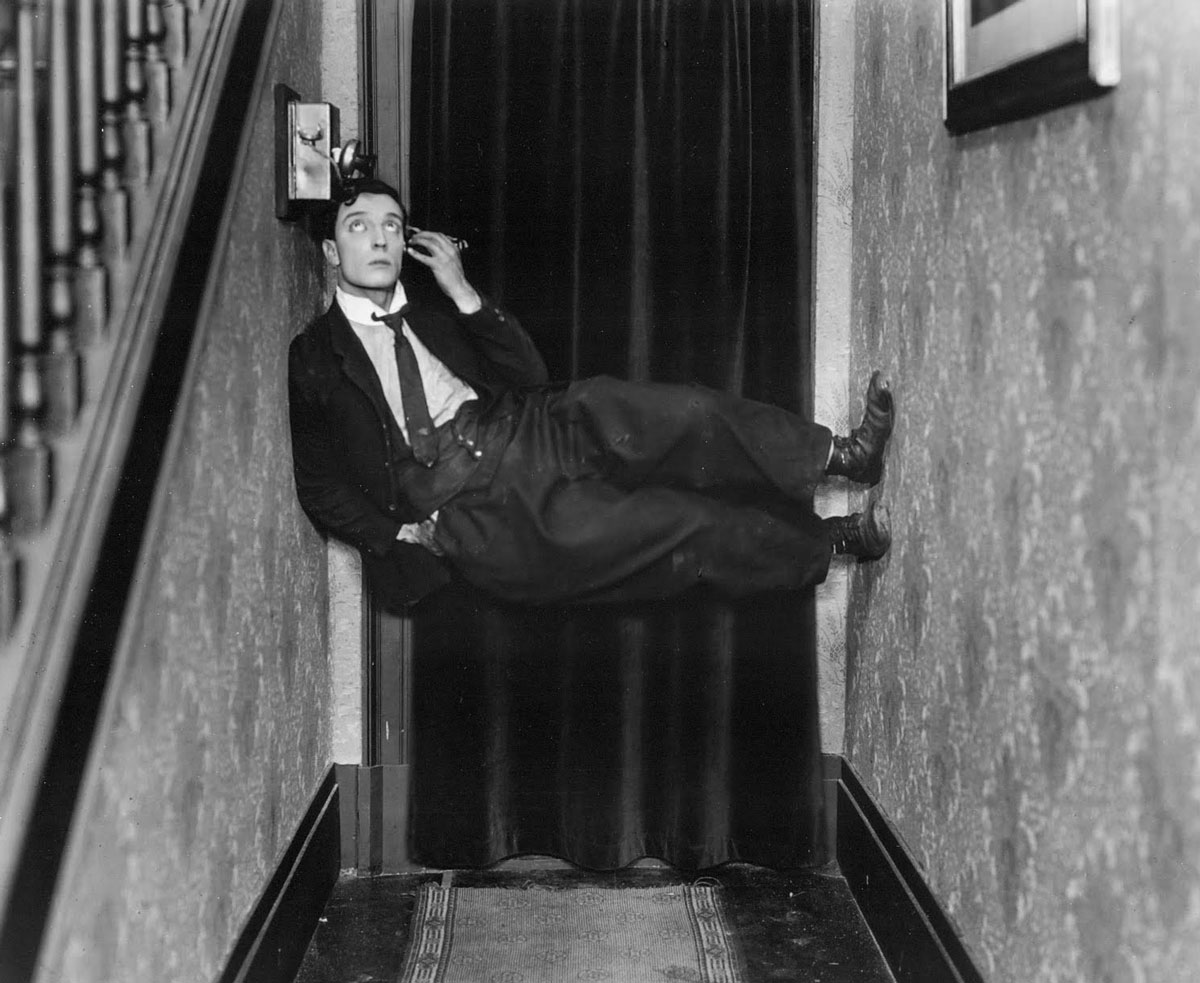

He lays out a game of solitaire. The room has a pool table in it, and a lot of old photographs. On the table between us there is a card that a studio magnate left stuck in his dressing-table mirror one day soon after the talkies had come in, giving him the sack in three lines. “In the Thirties, if there’s a silence,” says Buster, “they say there’s a dead spot.” Stills from his films come to mind: images of that noble gaze, austere and distinctive even when the head is up to the ears in water after a shipwreck, or when Buster is in mid-flight of some sort. Partly because of his vaudeville experience and partly because of his temperament, he obviously reserves great respect for those who retain a stoic attitude toward calamity and imminent death in the middle of being flung from one side of life to the other. He admires the character of a performing animal—a chimpanzee, as I remember, called Peter the Great—who expressed a Senecan-sounding serenity as he was being thrown around the stage of Buster’s childhood.

Keaton’s first film entrance was in The Butcher Boy. His character is clear at once. We are in a world of slapstick chaos, but he emits a sense of wary order. The scene is a village store. Everyone else moves around a lot, to put it mildly. When Keaton enters, the unmistakable calm asserts itself. He is wearing shabby overalls, and big shoes with a hole in one sole (which later turns out to be usefully open to some spilled molasses), and already the famous flat hat. He then goes quietly through a scene of almost aeronautic catastrophe and subsidence, the whole parabola photographed in one take. Only a child brought up in music-hall riot from toddling age could have done it. The shop—hung with posters promising “Fresh Sausages Made Every Month,” run by a Roscoe Arbuckle who puts on a fur coat to go into the freezer locker (Keaton never calls him Fatty; it is always Roscoe), and inhabited by a club of aloof cardplayers with Abe Lincoln faces clustered around a stove—turns into a whirlwind. Molasses sticks, and bodies fly, and flour powders the air. We are in a world of agile apprentices and flung custard pies and badly made brooms that Buster scathingly plucks by the individual bristle as if they were suspect poultry. And through it all there is the Keaton presence: the beautiful eyes, the nose running straight down from the forehead, the raised, speculative eyebrows, the profile that seems simplified into a line as classical as the line of a Picasso figure drawing. After a bit, Roscoe Arbuckle throws a sack of flour at him. Throughout his life, to many people, Buster has repeated his admiration of the force and address of that throw.

In spite of the peculiarly heroic austerity of his comic temperament, Keaton maintains firmly that he is a low comedian. This is a simple piece of old vaudeville nomenclature. “The moment you get into character clothes, you’re a low comedian,” he says. There are also, among others, tramp comedians and black-face comedians—a category that was stylized for purely technical reasons but that drew some of Keaton’s shorts into looking Uncle Tom-ish. “What you have to do is create a character. Then the character just does his best, and there’s your comedy. No begging.” This is the difference between him and Chaplin, though he doesn’t invite comparisons and talks a lot more eagerly about technical things. The system of vaudeville comedy that he works by is methodical, physically taxing, and professionally interpreted. “Once you’ve got your realistic character, you’ve classed yourself. Any time you put a man into a woman’s outfit, you’re out of the realism class and you’re in Charley’s Aunt.” There are one or two films of Keaton’s, early in his career, in which someone wears drag; leaving aside modern unease about transvestism, the device goes against what Keaton can do.

Keaton’s logical and vitally realist nature gradually got rid of the farfetched, or what he amiably calls just “the ridiculous.” His whole comic character is too sobering for that, though infinitely and consolingly funny. Nothing much changes, it says. Things don’t get easier. He will be courting a girl, for instance, and have to make way for a puppy, which the etiquette of the girl’s demonstrativeness demands that she hug; the proposal that he meant to make to her goes dry in his mouth. He leaves with an air. Seasons pass, the puppy grows to frightful size, and he is still outwitted by her intervening love of pets. Finally, against every sort of odds, and only by great deftness, he manages to marry her, but the chance of kissing her is still obligatorily yielded to others— to the minister, to the in-laws, to the rival suitor, and to the now monstrous slobberer, who ends the picture by sitting between the wedding couple on a garden seat and licking the bride’s face. All the same, whatever the mortification, Keaton is never a pathetic figure. His heroes stare out any plight. Perhaps because he has an instinctive dislike of crawling to an audience by exploiting any affliction in a character, including any capacity for being victimized, his figures never seem beaten men, and after a few experiments in his early work he never plays a simpleton. He has perfected, uniquely, a sort of comedy that is about heroes of native highbrow intelligence, just as he is almost the only man who has ever managed to establish qualities of delicate dignity in characters with money. Comedians don’t generally play the highborn. The fortunate, debonair, tongue-tied central character of The Navigator is one of the rarer creations of comedy: rich, decorous, possessed of a chauffeur and a fine car that makes a U turn across the street to his fiancee’s house, infinitely capable of dealing with the exchange and mart of high-flown social marriage, jerking no heartstrings. Keaton’s world is a world of swells and toffs as well as butcher boys, and mixed up in it are memories of his hardy past in vaudeville that give some of his films a mood of the surreal. In The Playhouse, which he made after breaking his ankle on another picture, he plays not only nine musicians and seven orchestra members but also a music-hall aquatic star, an entire minstrel show, a dowager and her bedeviled husband, a pair of soft-shoe dancers, a stagehand, an Irish char, and her awful child, among others. We see the Keaton brat dropping a lollipop onto the Keaton grande dame in the box below; the dowager then abstractedly uses the lollipop as a lorgnette. He also plays a monkey who shins up the proscenium arch— something that must have been rough on the broken ankle. The film has a peculiar aura, not quite like anything else he made. It is dreamlike and touching, with roots in a singular infancy that he takes for granted. Vaudeville is what he comes from, as powerfully as Shakespeare’s Hal comes from boon nights spent with Falstaff. In Go West, there is a music-hall set piece about a slightly ramshackle top hat that is kept brilliantly in the air by repeated gun shots. “It has to be an old hat,” says Buster. “You couldn’t use a new hat. Otherwise, you don’t get your laugh. Audiences don’t like to see things getting spoiled.”

Keaton has a passion for props. Especially for stylish things like top hats, for sailing-boats and paddle steamers, and for all brainy machinery. He finds ships irresistible. A short called The Boat forecasts The Navigator; there is also Steamboat Bill, Jr. Facing many calamities, Buster as a sailor works with a sad, composed gaze and a resourcefulness that never wilts. In Steamboat Bill, Jr., he leans on a life preserver that first jars his elbow by falling off the boat and then immediately sinks; Keaton’s alert face, looking at it, is beautiful and without reproach. In The Boat, where he is shipbuilding, though deflected a good many times by one or another of a set of unsmiling small sons, his wife dents the stern of his creation with an unbreakable bottle of Coke while she is launching it; Keaton helps by leaning over the side to smash the thing with a hammer, and then stands erect while the boat sinks quickly up to his neck, leaving us to watch the august head turning round in contained and unresentful bafflement. In Steamboat Bill, Jr., his last independently produced film, he turns up, looking chipper, to join a long-lost father who runs a steamboat. The son will be recognized by a white carnation, Buster has bravely said in a telegram delivered four days late. He keeps authoritatively turning the carnation in his lapel toward people as if it were a police badge. No one is interested. His father eventually proves to be a big, benign bruiser, and not the man his son would have expected; nor is Buster the sort of man his father instantly warms to. He is much put off by the beautiful uniform of an admiral that Buster wears to help on the steamboat. It is not, maybe, fit for running a paddle steamer, but it is profoundly hopeful. It represents an apparently mistaken dapperness and an admission of instinctive class that turn out to be as correct in the end as the same out-of-place aristocratism is in The Navigator, that poetic masterpiece of world cinema.

There is nothing anywhere quite to equal the comic, desperate beauty of the long shots in The Navigator when Buster, the rich sap, is looking for his girl on the otherwise deserted liner that has gone adrift. The rows of cabin doors swing open and closed in turn, port and starboard in rhythm, on deck after deck; the noble, tiny figure with the strict face and the passionate character runs round and round to find his dizzy girl, who is looking for him in her own quite sweet but less heartfelt way. The flowerfaced fiancée played by Kathryn McGuire is a typical Keaton heroine. She is rather nice to him when he has got into his diving suit to free the rudder and has forgotten, with the helmet closed, that there is a lighted cigarette in his mouth. (This is a mistake that apparently happened while Keaton was shooting. “They’ve closed the suit on me,” he says, coughing, the memory bringing on his present bronchitis, “and everyone just thinks I’m working up a gag.”)

Keaton’s characters are outsiders in the sense of spectators, not of nihilists or anarchists. He isn’t at his best when he hates people (unlike W. C. Fields, for instance—whom he talks about with regard, doing a brotherly imitation of the voice of men who are martyrs to drinkers’ catarrh). A short called My Wife’s Relations has some of the Fields ingredients, but Keaton muffs the loathing. The picture has its moments, though. The wife is a virago with Irish relations who are devout but greedy; the only way to get a steak, Buster discovers, is to turn the calendar to a Friday. The blows that he manages to give her in bed when she thinks he is only thrashing in his sleep are pretty funny. So are the hordes of rapacious brides in Seven Chances, rushing after him on roller skates and wearing improvised bridal veils to make a grab for him because he will inherit a mint if he marries by seven o’clock.

But Keaton is really at his best when he is being rather courtly. He has great charm in a feature called The Three Ages—about love in the Stone Age, the Roman Age, and the Modern Age—when he stands around among primordial rocks in a fur singlet and huge fur bedroom slippers chivalrously helping enormous girls up boulders. In that Age, prospective in-laws assess the suitors by strenuous blows with clubs, and people ride around on mastodons that are clearly elephants decked out with rococo tusks by Keaton’s happy prop men. In the Roman Age episodes, Wallace Beery as the Adventurer has a fine chariot, and Keaton has a sort of orange crate drawn by a hopeless collection of four indescribable animals. The Romans throw him into a lion’s den, but he thinks of only the pleasantest things to remember about lions, which is that they behave well if you do something or other nice to their paws. He takes a paw, washes it, manicures it, and dries it. The interested beast responds affably. We switch back to the Stone Age. Keaton, looking more than usually small in the surroundings, is dealing courageously with the colossal opposite sex while hoping privately for more lyric times. He gets them for a moment in the Roman sequences; there is a wonderful shot of a girl’s worshipful face as she thinks of Buster when she is in the middle of being pulled by the hair in some impossible Roman torment. But nothing vile in antiquity, Keaton implies by the sudden, pinching end of this revue-film, can equal the meager-spiritedness of Los Angeles; the Stone Age and the Roman Age episodes both finish with shots of Buster and his bride surrounded by hordes of kids in baby fur tunics and baby togas, but the Modern Age episode finishes with the happy couple walking out of a Beverly Hills house followed by a very small, spoiled dog. Such minutes of tart melancholy are often there in Keaton. They go by fleetingly and without bitterness, like the sad flash in The Scarecrow when a girl takes it that his kneeling to do up a shoelace means that he is proposing. His beloveds sometimes have overwhelming mothers; one battle-ax, in The Three Ages, causes a pang when she makes him produce his bank balance, which is in a passbook labeled “Last National Bank” and obviously not up to scratch. One thinks, inevitably, of the hard time that Keaton was to have with his ambitious actress wife, Natalie Talmadge, which left him flat broke when the talkies came in. The Keaton hero, with the scale he is built on, and with his fastidious sense of humor, is obviously the born physical enemy of all awesome women. The girls he loves are shy and funny, with faces that they raise to him like wineglasses. But his idyllic scenes are very unsentimental. There is a nice moment when his loved one in The Navigator says to him, in reply to a proposal of marriage, “Certainly not!” Chaplin was once said to have given comedy its soul; if so, it was Keaton who gave it its spine and spirit.

“They have too many people working on pictures now, you know,” says the aging, unsoured man whom the talkies threw on the dustheap although he could probably have gone on making great films in any new circumstance, and on a minute budget, and editing in a cupboard. “We had a head electrician, a head carpenter, and a head blacksmith.” The blacksmith seems to have been crucial. There was a lot of welding to do. Keaton himself did his stunt work, magically and beautifully. Who else? He could loop through the air like a lasso. When he is playing the cox in College and the tiller falls off the boat, it is entirely in character that he should dip himself into the water and use his own body as the tiller. The end of Seven Chances is an amazing piece of stunt invention, inspired by cascades of falling boulders, that would have killed Keaton if he hadn’t been an acrobat. Most of his stunt stuff isn’t the sort of thing that can be retaken, and Keaton doesn’t care much for inserts. “I like long takes, in long shot,” he says. “Close-ups hurt comedy. I like to work full figure. All comedians want their feet in.”

He has just been asked to the premiere of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, which he has a part in after spending decades doing nothing much but commercials. Mad World is in the mode of wide screens with a vengeance. Buster has seen the picture. It can’t be much to his taste, but he doesn’t say so. He likes working; even making commercials doesn’t strike him as such a cruel outcome to a life. He wants to go to the premiere. He looks vigilant and spry.

The wife of his last years thinks he shouldn’t go to the premiere, because he might get a coughing fit and have to leave.

“We have aisle seats,” he says.

“You’re not well,” she says.

“I can take my cough mixture,” he says. “I can take a small container. I can get ready to move in a hurry.”

May 24, 1964

June 18, 1967

September 26, 1970

San Fernando, California

Originally published in The New Yorker