The Garfield Movie (2024) | Review

Adventure, slapstick, and sentiment blend in the sixth big-screen outing of the voracious cat: Dindal and Reynolds (The Emperor’s New Groove) are a reliable duo.

Adventure, slapstick, and sentiment blend in the sixth big-screen outing of the voracious cat: Dindal and Reynolds (The Emperor’s New Groove) are a reliable duo.

MOVIE REVIEWS Just the Two of Us (2023) French: L’Amour et les Forêts Directed by Valérie Donzelli When Blanche crosses paths with Grégoire, she believes

The portrait of the German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer, one of the most innovative and significant artists of our time, captures his life, vision, revolutionary style, and immense body of work exploring human existence and the cyclical nature of history.

Abel is a high school student struggling to focus on his final exams, while being hopelessly in love with his best friend Janka.

On April 23, 1958, Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil” was released in American theaters. It contains one of the most moving deaths and epitaphs in the history of cinema.

“Challengers” blends tennis with cinema theory, exploring relationships and visual storytelling in Luca Guadagnino’s unique style.

Based on a novel by Thomas Keneally, which in turn is based on a true story, “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” is about a rampage.

Pauline Kael explores the exuberant artistry of Abel Gance, particularly in his film Napoléon, lauding his ability to blend avant-garde filmmaking techniques with a melodramatic and romantic flair

The great Australian film “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” is a dreamlike Requiem Mass for a nation’s lost honor

How “Civil War” uses photography to challenge viewers’ reality perceptions

Alex Garland’s ‘Civil War’ offers a stark vision of a divided America.

Hoping it’s not too prophetic, the onslaught of new movie releases brings few must-sees; however, among them is “Civil War” by the ingenious Alex Garland.

Powell & Pressburger balanced high & popular cinema, creating iconic films like “The Red Shoes,” a melodrama with a fairy-tale twist, blending art & emotion.

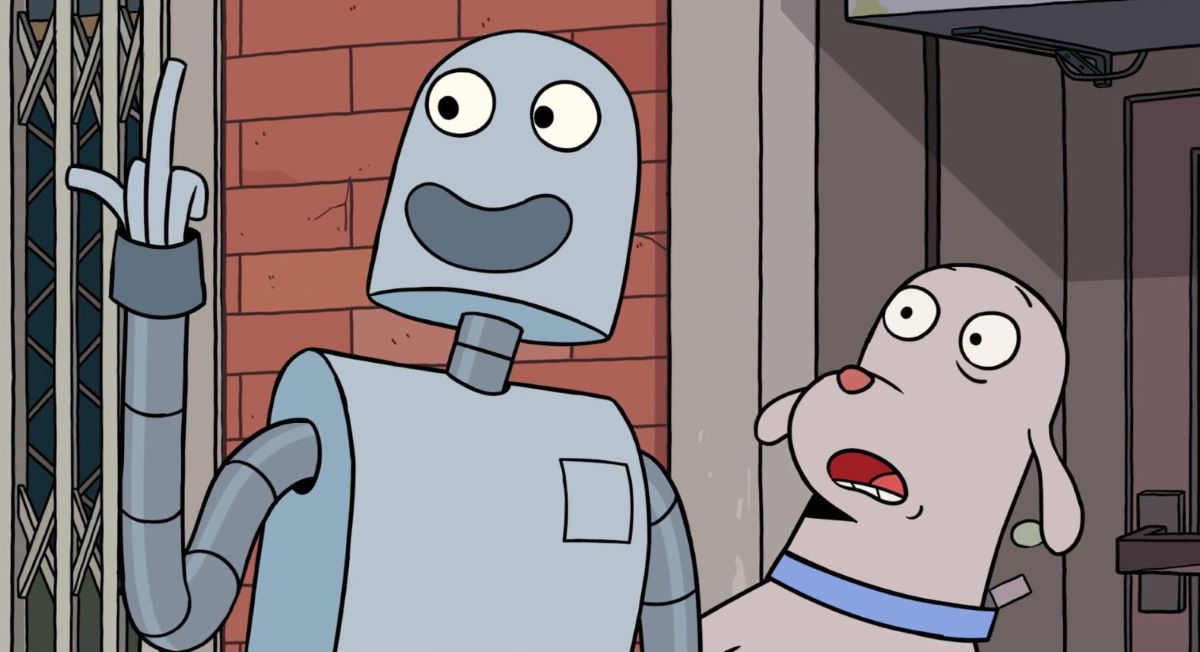

MOVIE REVIEWS Robot Dreams (2023) Directed by Pablo Berger DOG lives in Manhattan, and tired of always being alone, he builds a robot. Set to

The wave of musical biopics has not spared Amy Winehouse: Marisa Abela avoids caricature, but the film remains superficial, teetering between hagiography and marketing.

Luca Guadagnino’s melodramatic love triangle reveals the limitless possibilities hidden within the confines of a tennis court: Zendaya’s star has never shone as brightly as it does this time.

Rosa, heart of old Marseille, balances family, work, and activism. As retirement nears and doubts rise, she finds it’s never too late for dreams.

During the world judo championships, Iranian judoka Leila and her coach Maryam receive an ultimatum from the Islamic Republic instructing Leila to fake an injury and lose the match, or else be branded a traitor to the state.

The saga of Damien begins again with the prequel: a non-trivial horror that reflects on possession from a feminist perspective.

Review: Robot Dreams skips dialogue for a beautiful story of a dog and robot’s bond. A heartwarming & unforgettable film.

Cristiane Oliveira’s ‘Até que a Música Pare’ blends loss, love, and cultural heritage into a narrative that captivates and heals.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!