Poetry and Politics

by Pauline Kael

The movie of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle goes against the grain of all those old movies in which the heroes struggled to complete an invention or to perform a feat while inwardly, in our childish souls, we cheered, sharing the heroes’ victories as they won fame and fortune. For the prisoners — or zeks — in this movie, heroism means destroying their inventions and refusing to carry out the tasks that might win them freedom and honors. Unlike Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which deals with an Everyman, a mere dot, in the slave-labor camps, The First Circle is a view of the top echelon of the slave-labor world — the mathematicians, scientists, engineers, and professors working in a technical institute near Moscow. They have spent years in the labor camps — they have survived the bottom — and now they are, as the novelist puts it, in “the highest, the best, the first circle of Hell.” The tasks assigned them are to solve “security” problems: the government wants a device for putting a hidden camera in a door so that everyone who opens the door is automatically photographed; the government wants a scientific method of identifying people by their voice patterns so that incoming calls on monitored phones can be traced; and other such projects. These prisoners can improve their own situations only by helping to entrap others, and they succeed — as human beings — by deliberately failing. They know what the consequences will be, and the movie brings us to an awed admiration of their heroism; though we can’t quite cheer, we draw in our breath, feeling, now, like adults.

The movie isn’t drab —- which is what one may fear. It’s tense and inspiriting: not a great film but good enough to dramatize Solzhenitsyn’s themes and to leave us facing the issues the novel raises — the moral and intellectual choices left open to the prisoners. It isn’t often that a movie tries to engage us in one of the central political experiences of our own time, and it’s far from simple to re-create modern Russia — the novel is set in 1949 — without Russians. Alexander Ford, the well-known veteran Polish director, who was for many years head of the Polish film industry, left Poland in 1968, because of the anti-Semitic persecutions, and he made this film in Denmark as a Danish-German co-production. The film is in English, and I can’t see how one can rationally object. The performers are Scandinavian (mostly Danish), Polish, and German; they spoke their lines in English — accented, of course — and then, under the director’s supervision, non-accented voices were dubbed in. Under the circumstances, it’s an almost impeccable solution, because the somewhat uncharacterized, impersonal voices make the argument of the film very easy to follow. The camerawork, the subdued color, the editing are all craftsmanlike; Ford must be a very modest man, deeply engaged with the material, because he doesn’t intrude between Solzhenitsyn and us.

The high intelligence of this movie is that it does not try to replace the novel. The book has that density of episodes and individual stories and interconnected lives which makes for a great “read.” The picture of the new Soviet bourgeoisie and the discussions within the prison about supporting the regime have the richness of high journalism, and the sudden, majestic big scenes — such as the arrest of Volodin, the young state counselor in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs — stay in your memory. In the movie, you lose that spacious, beautifully controlled outpouring of incident; you lose the orchestration of the themes, and what some might call the Russianness. Ford eliminates characters and telescopes others, and he doesn’t try for the contradictions within them, or the depth. Some of the big scenes are in the movie, and they’re not great scenes now, but, if their sublimity is lost, you can still get their import. I think Ford’s approach is sound: what makes most movie adaptations of novels of the first or second rank so embarrassing is that the director tries to rival the author. The movie becomes a pop vulgarization, which is then advertised as if the movie itself were a classic. The acceptance of pop has become a self-putdown for many of us; when we see a movie in which people behave like adults, we come out feeling clean, for a change. There is no pop distortion here, nothing tinny. By concentrating on the themes — on precisely what is most controversial — the movie performs an inestimable set-vice. In the book, Solzhenitsyn’s great gift of specificity and the other pleasures of his narrative crowd out one’s niggling doubts about what he’s saying. The movie, stripping away those pleasures, brings us to confront the material politically.

Structurally, Ford is very faithful. The action begins with the phone call that Volodin (Peter Steen) makes to warn an eminent professor — who as a doctor had saved Volodin’s mother’s life — that he may be arrested. Then the action moves to the life within the prison-institute during the three days in which experiments conducted there lead to Volodin’s arrest. Volodin enters the prison just as a group of obstructionists, including the hero, the mathematician Nerzhin (Gunther Malzacher), are being sent back to the lower rungs of Hell, where they may expect to rot and perish. The movie is faithful even to a defect in the novel: as we become involved with the prisoners, we lose track of the imminent danger to Volodin, and it isn’t until we hear the tape of his phone conversation being studied in the institute that we are brought back to the story line. It may be a defect in both novel and film that there is no real suspense — that it is only a matter of time before Volodin is arrested. That is, in Solzhenitsyn’s vision the police apparatus is like a doomsday machine, so incredibly, fatally efficient that nobody can get by with anything. This isn’t necessarily based on actual observation. For the author’s purposes, the superficialities of chance are unimportant, and it doesn’t really matter if Volodin escapes detection this time; sooner or later the impulse that led him to warn the professor will land him in prison. And what Solzhenitsyn is concerned with is how an individual in the extremity of suffering finds his humanity. I think this is why the spring of the trap as Volodin is caught doesn’t have the effects of suspense that it would in an ordinary melodrama, in which we would have been sweating it out with him and hoping for his escape.

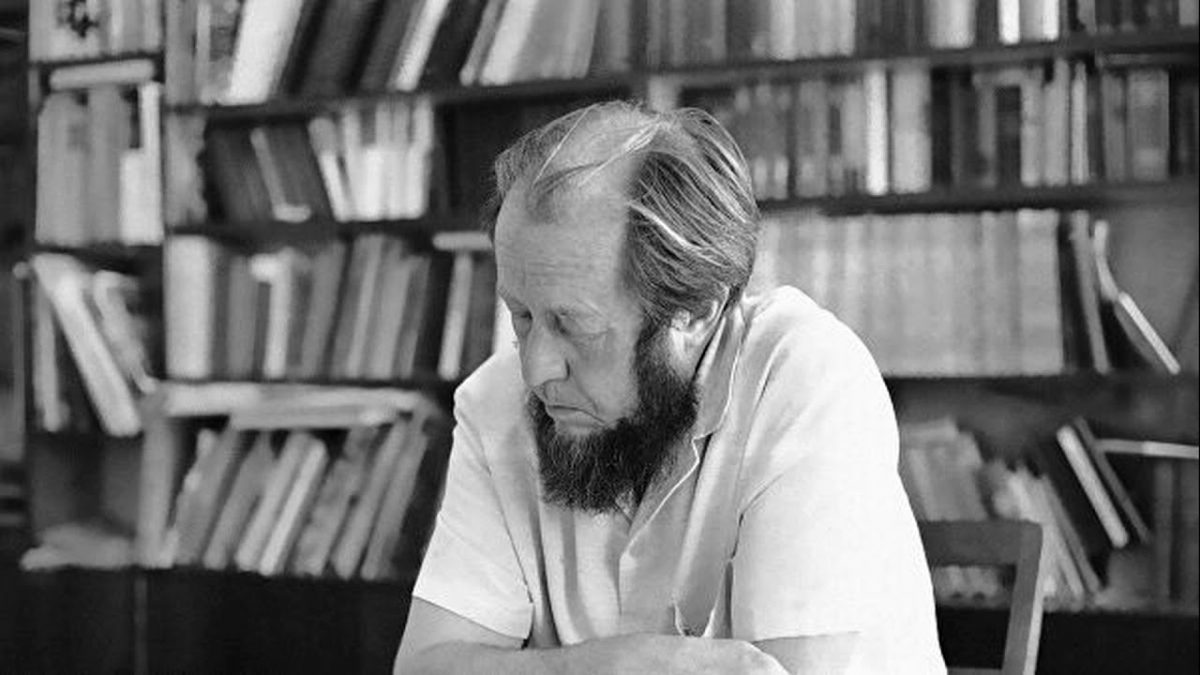

In the movie, Nerzhin, a man much like the author (who is also a mathematician), is given some of the action that the designer Sologdin is assigned in the book, and also bits of Gerasimovich, the physicist (both these characters have been eliminated), but Nerzhin takes on the additional burdens with ease, since all three characters appear to speak for the author. Malzacher, a lean actor with an intelligent manner (a little like Richard Basehart), is successful in suggesting that Nerzhin is satirical and amused about his own adamant gadfly nature — that his irony includes his own loftiness. What Malzacher doesn’t suggest is that look of a man from an earlier century which we begin to see in the photographs of the bearded Solzhenitsyn — the severe look of an Amish elder. This Solzhenitsyn is the greatest poet of freedom, and his integrity gives him an intimidating moral authority, but his aura of intellectual clarity can be deceptive. It is too easy for us to blur the distinction between two ideas; one, that in an oppressive system if you try to act like a human being you risk martyrdom, and that martyrdom may be your only way not to lose your self-respect; and, two, that this martyrdom will bring down the system. The first is not difficult to believe, though Solzhenitsyn himself carries it further than we may assent to; in the novel, he has Gerasimovich thinking that “those who were free lacked the immortal soul the zeks had earned in their endless prison terms.” The second idea, however, is slippery. The First Circle is the story of a moral victory — of Nerzhin, primarily, but of others also — but in the terms of the novel and the movie this moral victory defeats the oppressors. Harrison Salisbury, who is quoted on the cover of the book, said in the Times Book Review, “It is not in the end the prisoners who are destroyed, even though they may lose their lives. It is the jailers. … It is the oppressors who are doomed.” For Solzhenitsyn the oppressors may be spiritually doomed, but that shouldn’t be confused with actual political doom. We must, of course, believe in moral courage, but as an end in itself — as the realization of what man can be. It would be immaculate justice if moral incorruptibility destroyed the corrupt, but that goes back to the high-minded naivete we had as children, when we overestimated the power of words and believed that virtue would conquer all, without a fight, just in the nature of things.

Because Solzhenitsyn, in his beautiful, stiff-necked intransigence, clearly makes a difference in the world, we are in danger, I think, of accepting his Christian mysticism as if it were a political solution. His heroes become stronger in themselves when, at the end, they are “filled with the fearlessness of those who have lost everything, the fearlessness which is not easy to come by but which endures.” They are resigned but not broken. It is, of course, a great triumph, but it’s a peculiarly insulating personal triumph. And although the assumption that the spiritual strength of men who have lost everything will defeat the oppressors may be a psychological necessity for the heroes, it is, when viewed from the outside, heavenly rhetoric. When you get to the point of believing that the acceptance of powerlessness is true power, you’re no longer talking about the visible world.

Deep in the author’s writing — and even in his face — one can feel the belief that man was put on this earth to suffer. And this has somehow got mixed with the idea of defeating your enemies by the purity of your suffering. But your gestures may do more for you than to them. It is not really surprising that this great Christian novelist should spring from the Soviet Union: totalitarianism drives one to the last outpost — fighting to save your soul (which, psychologically, may not be so very different from American blacks fighting for their manhood). But it’s easy for us to overvalue our own suffering, romantically. An individual here may immolate himself assuming that his suffering will change the world, that the people who don’t care about the deaths of thousands — of millions — will be transformed by his. (Does he perhaps think that one white charred body will do what all the brown corpses can’t?) The truth of political life is even more horrible than Solzhenitsyn’s truth. We can certainly believe that in the Soviet Union the heroes are in the camps, if by “the heroes” we mean the irritable or defiant people who express their revulsion at the social order, even though only inadvertently. But are they fortunate to be there, as (in some strict, recondite area of his mind) Solzhenitsyn sometimes seems to think — earning their immortal souls? Nerzhin-Solzhenitsyn, shoving his contempt down the oppressors’ throats, is a strong, robust hero, a dissenter with the humor of his rectitude. And Solzhenitsyn himself, as the survivor of everything “they” dished out, is the greatest symbolic artist-hero in the modern world. But politically, despite the intelligence of his descriptive passages, he looks toward some special mystical endowment of the Russian people. And that famous Russian soul doesn’t seem to come through in political life — it comes through only in novels. Probably what comes through in political life in the Soviet Union is what comes through in political life here now — hopelessness, apathy, suspicion, fear, cynicism, violence.

What gives the movie its impact is how close the whole situation feels to us, and Solzhenitsyn is inspiring because many of us feel that we, too, need moral leadership. But I was bothered in the novel by Volodin’s saying, “After all, the writer is a teacher of the people. … A greater writer is, so to speak, a second government.” And I was bothered, too, by the words of Solzhenitsyn’s undelivered speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970: “One word of truth shall outweigh the whole world.” (If it did, the Vietnam war would have ended — would never have started. If it did, editorial writers wouldn’t have to go on saying the same things over and over.) When Solzhenitsyn speaks those words, he takes risks, and the words have political consequences, but people who believe that one word of truth will really outweigh the whole world are mistaking poetic power for political power. Yet I think that at times we all play this game with ourselves. Solzhenitsyn’s own depth of feeling is not in question. He sets a peerless example that lifts our spirits, but our exaltation may allow us to feel that evil can be dealt with by poetry alone. We react the way we react to a stargazing valedictorian: we can see that he believes what he’s saying, and we find his belief inspiring because we want to believe. We respond to the beauty of the message. But we know that when more people actually believed that the poetic truths would conquer, it didn’t improve their social conditions; it merely helped them to bear their suffering. There’s a soaring upbeat element in The First Circle — an old-fashioned Christian Russianness — that may have helped to make the book popular. At the end of the novel, when the group, including Nerzhin, is being transported to Siberia, Solzhenitsyn writes:

Yes, the taiga and the tundra awaited them, the record cold of Oymyakon and the copper excavations of Dzhezkazgan; pick and barrow; starvation rations of soggy bread; the hospital; death. The very worst.

But there was peace in their hearts.

The challenge of the movie — coming to us at this time — is that even though we’re not living in a totalitarian state, and we know that the hopelessness Americans now feel isn’t fully justified, we fear increasingly that the only self-respecting choices that are left us may lead to martyrdom. That “peace in their hearts” is maddening, because we haven’t got peace in our hearts, even in its simpler forms. But in Solzhenitsyn’s form it’s spiritual solace when everything else is gone.

The New Yorker, January 20, 1973