El Poto-Head Comics

by Pauline Kael

The atmosphere in the theatre is enough to inform you that El Topo is a head film, but while I was watching Alexandro Jodorowsky’s horror circus I was nevertheless puzzled about why the mostly young audience sat there quietly — occasionally laughing at a particularly garish murder or mutilation — while the few older people staggered out in disgust. At one point, I drew in my breath sharply at the prospect of another slaughter scene, and a pretty, blank-faced girl sitting in front of me with her boyfriend’s arm on her shoulder turned her head slightly toward me, as if to say, “What’s the matter with her? Is she taking it seriously, or something?” And I realized that I and those older people who left — I would have joined them if I had not had a professional interest in seeing the film — were responding on a different level from the rest of the audience, part of which had probably already seen the film before its official opening last week, during the six months it played at midnight screenings, like a Black Mass. This film that they return to over and over doesn’t need reviews (not in the overground press, anyway) to lure an audience, but maybe it’s up to reviewers to try to explain why that audience is being lured.

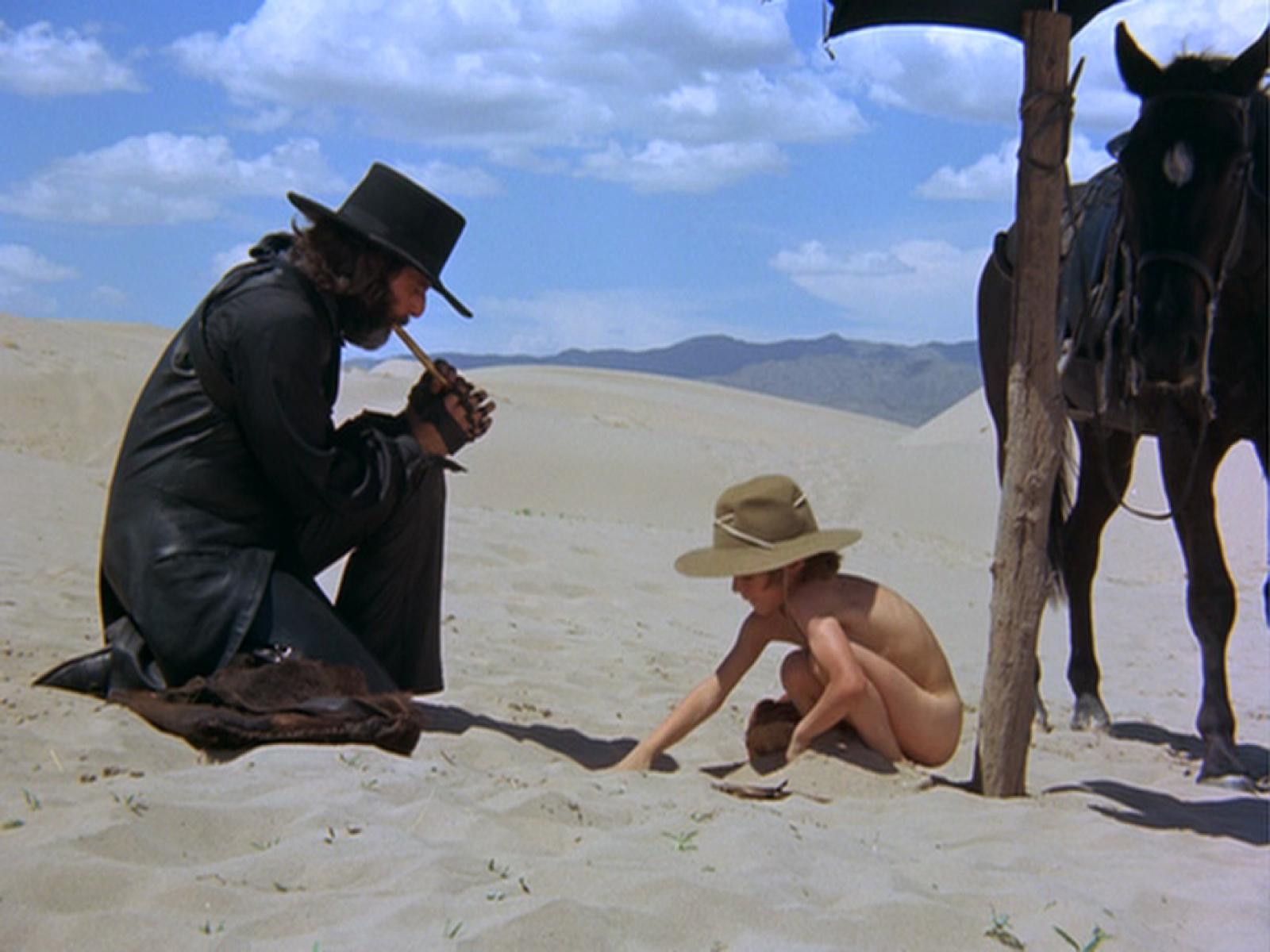

Jodorowsky, born in Chile in 1930 of Polish-Russian-Jewish parentage, was once a member of Marcel Marceau’s company and composed some of Marceau’s pantomimes; he is now a theatre director in Mexico, and a cartoonist as well, whose weekly comic strip “Fabulas Panicas” (or “Panic Fables”) appears in a major Mexico City newspaper. El Topo (it means “The Mole”) was made in Mexico, and it resembles the spaghetti Westerns. It begins with a bearded stranger in black leather (Jodorowsky) riding on a sandy plain; the color looks cheap and overbright, unreal in that gaudy way that unsophisticated attempts at realism often produce — it’s like Kodacolor, with aquamarine skies. But the stranger rides with his naked son sitting behind him, and it is immediately apparent that the nakedness is symbolic — the more so when the father says, “Now you are a man. You are seven years old. Bury your first toy and your mother’s picture,” and the burial ceremony consists of propping the symbols up in the sand. And when the father and son come to a town, the town is a scene of more than usual spaghetti-Western carnage. It is a town of corpses and entrails; animals, children — everyone has been butchered, and the waters literally flow red. The bearded man in black becomes the gunfighter, the avenger; he tracks down the murderous bandits and castrates their warlord. Then, with the words “Destroy me. Depend on no one,” he leaves his son with a group of young monks whom he has liberated, and takes up with the warlord’s mistress. Up to this point, the carnage has been steady, and with quantities of fetishism and perversion. (As captives of the brigands, used for sexual sport, the young monks had bloodstained bare bottoms.)

In the next section, the picture becomes more occult, and more like a fairy tale, as the man in black and the woman, whom he christens Mara, go into the desert, where she persuades him that he must conquer the four masters who dwell there. The masters being different varieties of holy men, each of the four contests is enigmatic, and in this section the characters converse in high-flown riddles — a sort of Zen, Confucius-say talk (“The desert is a circle”). The hero wins his contests by trickery and realizes too late that he has truly lost, and cries out to ask why God has forsaken him. Meanwhile, Mara has been joined by a sadistic lesbian in butch black couture, and as he thrashes about in guilt for his crimes, battering himself against walls that crumble, the lesbian comes at him, like Mercedes McCambridge in Johnny Guitar, and pumps lead into him; he keeps walking, arms outstretched and with stigmata on his hands and feet, until Mara shoots him down. The women kiss — tongues extended — and leave him for dead. A group of dwarfs and cripples lug his body off. Can it be the end? No, there is a third section.

Years have passed — perhaps twenty. He sits as a holy man in a cave in a mountain, tended by a worshipful dwarf woman. Spiritually reborn, with his beard and head shaved in penitence, he pledges himself to liberate the tiny, shrivelled cave people, who are now trapped in the mountain, imprisoned there by the people of a nearby town, so that the townspeople will not have to see the deformed results of their generations of incest. The holy man begins work on a tunnel; because of his height, he himself can scale the walls of the cave, and he comes and goes, taking the woman dwarf with him. When they go into the town, we are once more back in a Western. The town is a synthesis of the gambling, whoring saloon towns of American movies, with a cartoon catalogue of evils: blacks are sold as slaves and branded, accused of rape by lecherous women, lynched, and so on. The penitent cleans toilets in the town jail and becomes a clown — God’s fool — in order to buy dynamite to blast the mountain open. When he and his little woman (the only good woman in the entire film, and good by virtue of her total selfless devotion to him) go to the church (where the parishioners normally play Russian roulette) and ask to be married, the priest turns out to be the abandoned son. The three of them go back to the mountain to free the cave people; once free, however, the crippled, helpless little monstrosities — they’re like deformed Munchkins — rush to see the wonders of the town, and the townspeople meet them with rifles and shoot them down. The holy man arrives too late; they have all been massacred. He yells and is shot, and is shot again and again, but he keeps coming toward the townspeople, like a Golem. Full of holes (like Toshiro Mifune’s porcupine Macbeth full of spears in Throne of Blood), he picks up a gun and, once more the avenger, retaliates by slaughtering the townspeople. Seated then, cross-legged, he soaks himself in kerosene from a Western lamp and immolates himself (successfully). A new holy family — his son, bearded and dressed in black, and his dwarf widow, carrying his newborn baby, ride away into the whatever the movie began from.

Blood-soaked and piled high with deformity, the film is commercialized Surrealism. El Topo has been called a Zen Buddhist Western, but in terms of its derivations it’s a spaghetti Western in the style of Luis Buñuel, and tinsel all the way. The avant-garde devices that once fascinated a small bohemian group because they seemed a direct pipeline to the occult and “the marvellous” now reach the new mass bohemianism of youth. But the marvellous has become a bag of old Surrealist tricks: the acid-Westem style is synthesized from devices of the once avant-garde — especially L’Age d’Or and the whole lifework of Buñuel, with choice lifts from Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet, too. In El Topo, a brigand out on a rocky terrain sucks a woman’s pink slipper, and then a collection of women’s slippers are set up on the rocks as targets for shooting practice. An armless man and a legless man he carries on his shoulders function as one person — stumps exposed, of course; when shot apart, the helpless sections writhe on the ground. A man cuts a banana with a sabre. Crowds in the Western town applaud murders as if they were theatrical events. The lesbian lashes Mara’s back, licks and kisses the wounds, and then offers her blood-smeared face for Mara to kiss. Even the dwarf woman is forced into a sex show by the lewd townspeople, and must remove her blouse and expose her pathetic little body. And not just to them but to us.

Bizarrely complicated though it is, one can follow the story without difficulty. The movie may seem bewildering, however, because the narrative is overlaid with a clutter of symbols and ideas. Jodorowsky employs anything that can give the audience a charge, even if the charges are drawn from different systems of thought that are — as thought — incompatible. For example, he gets a lot of mileage out of the viciousness of lecherous, sex-starved fat old women gloating over murders, pawing a young black boy to the accompaniment of pig noises on the track, and taking up rifles to mow down helpless, stunted children on crutches; it’s a further distortion of the conventional distortions of Freudianism in American movies. But the movie is not a Freudian movie; if it were, the saintly love between the hero and the selfless, crippled dwarf might look pretty funny, but for that Jodorowsky shifts gears to penitential piety. One enthusiast of the film, who characterized it in an article in the Sunday Times as “a monumental work of filmic art,” described Jodorowsky as “a man of passionate erudition in matters religious and philosophical, which he draws on with the zest of the instinctual thinker for whom ideas are sensuous entities.” Well, of course, you don’t need erudition to draw on matters religious and philosophical that way — any dabbler can do it. All you need is a theatrical instinct and a talent for (a word I once promised myself never to use) frisson. Jodorowsky is, it is true, a director for whom ideas are sensuous entities — sensuous toys, really, to be played with. By piling onto the Western man-with-no-name righteous-avenger form elements from Eastern fables, Catholic symbolism, and so on, Jodorowsky achieves a kind of comic-strip mythology. And when you play with ideas this way, promiscuously — with thoughts and enigmas and with symbols of human suffering—the resonances get so thick and confused that the game may seem not just theatre but labyrinthine, “deep”: a masterpiece. I used the term “enthusiast” deliberately; the same writer describes the worshipful audiences and is himself among the worshipful, who treat El Topo as if it were the movie equivalent of a holy book. It is taken to be deep in the same sense that The Prophet used to be; “a work of incomprehensible depth,” another enthusiast called it, and, still another, “an indescribable masterpiece.” El Topo is really “The Bloody Prophet.”

At the beginning, when the gunfighter in black is asked, “Who are you to judge me?,” he replies, “I am God,” and after punishing those who are not good enough to live he immolates himself because of the evil in the world. Unlike Buñuel, whose Surrealist techniques cracked open conventional pieties, Jodorowsky uses those techniques to support a sanctimonious view: Man-God tempted by evil, power-hungry woman abandons righteous ways and then, with the love of a good woman, becomes spiritual man, only to learn that the world is not ready for his spirituality. The movie uses Catholic symbols for depth much the way symbols were used to deepen On the Waterfront, or the way the directors of American-made Westerns hang a cross around the neck of a poor Mexican whore. Catholics may be losing belief in the magical power of artifacts, but moviemakers still squeeze crosses for the last drops of superstitious thrill. Titles flash on the screen — “Genesis,” “Prophets,” “Psalms,” “Apocalypse” — like “Powie!” in a cartoon. They inflate the meaning of what you actually get. The Eastern riddles and prophetic utterances are used the same way, only they’re cute — lisping profundities. But, of course, those who are drawn to the movie can say, “What’s the matter with putting it all together? Everything is Everything.” Or, as someone actually wrote, “El Topo is the all-inclusive myth, the Jungian archetypical dream of love/death, power and glory, body and spirit.”

What makes it a head hit? Jodorowsky is not totally untalented; he has some feeling for pace and for sadistic comedy, and he seems to get the performances he wants. But he wouldn’t be called a great master if he were being judged simply as a film director; enthusiasts think of him as a visionary, and even as a saint. Jodorowsky doesn’t treat horror seriously as horror but, rather, treats it as both commonplace and somewhat funny — and, in a way, reversible. People in cruel comics who have their heads cut off sometimes put them right back on. The movie has a comparable buffoonishness about death — as, indeed, the spaghetti Westerns often have, but there is more of it here. It’s a death romp, and the young audience appears to accept the film as no more “real” than the experiences they have in their skulls on drugs. That’s why the blood doesn’t bother them; that’s why they don’t gasp at knife thrusts or castrations, and why they’re not repelled, either. I don’t mean to suggest that this film appeals only to heads, or only to the pot generation (roughly, those who use marijuana frequently and trip out occasionally); there are others — probably some of the parents of the pot generation — who share in the sensibility, and still others who try to in order to feel in touch with youth. But El Topo has the right properties for a head film — the glaring color, the excesses and anomalies, the comic-strip jumble of periods and places, cacophonous music alternating with camp music and screeching bird sounds, women who speak with men’s voices, primitive settings, nameless universal characters, porno eroticism, prophecies, transformations, rituals, miracles, and a sacrificial, somewhat paranoid vision. El Topo is all freaked out on love and mystery. And it’s violent.

The confusion in talking about this film with someone who thinks it’s a masterpiece comes from the fact that many heads consider their actual drug trips to be aesthetic experiences, and their only criterion for judging certain movies — head movies, especially, but some others, too — has become the intensity with which the movies hit them. I do not believe they would flock to El Topo and return to it if it were not for the violence. And, although I’m certainly not an authority on marijuana or on drugs, it seems obvious why: If the intensity of your sensations is what you judge a movie by, then the more shocks and dislocations and bloody thrills the better. On the one hand, the violence doesn’t bother the heads, because they don’t take it for real — it’s a trip, a fantasy experience, separate from day-to-day living. On the other hand, the violence is what blows their minds. Devices from the theatre of cruelty are used to set off kicky fantasies. The cruelty becomes delectable, like the gore. I look at the screen and I know that the animals being slaughtered aren’t plaster — not in Mexico, they’re not — and I look at the cripples exhibiting their sores and shrunken limbs, which aren’t plaster, either. And I react to the brutality, because I still associate violence with pain. But my guess is that for the head-movie audiences violence is dissociated from pain and is the richest ingredient of fantasy. It’s the violence that turns them on.

I would not presume to guess whether there are dangers in this; I just don’t know enough. But I do think this is at the core of why some of us want to walk out while others are having a big experience. One enthusiast wrote that the audience was “intoxicated” by the blood, another that “El Topo runs red, with castrations, beheadings, shootings, and mass murders which make the Sharon Tate scene look like kindergarten fare.” Jodorowsky uses violence, just as he uses the collection of cripples, to excite the audience, to help it fantasize, and I don’t imagine that the young audience drawn to this film sees anything wrong with that, since indeed it does excite fantasies in them, and that is basically their criterion for a great movie. But I do see something wrong with it, and I feel it the more strongly because Jodorowsky’s fundamental amorality isn’t even honest amorality. He’s an exploitation filmmaker, but he glazes everything with a useful piety. It’s the violence plus the unctuous prophetic tone that makes El Topo a heavy trip. The filmmaker-star says, I am God and I sacrifice Myself for your sins; I am Christ-turned-killer for your sins. The whole movie is an act of self-worship, a narcissist’s Mass, and it sells mystical violence at just the moment when the counterculture is buying mystical violence. Who would have thought that in the twentieth century Americans would become Spaniards?

Exploitation filmmakers have always specialized in sex or shock (or a combo), and their greatest virtue — their only virtue, really — has been how nakedly they sold it. Hollywood might titillate and pour on the sentimentality, but the exploitation men weren’t such hypocrites; besides, they didn’t have the means to pour on sentimentality. Jodorowsky has come up with something new: exploitation filmmaking joined to sentimentality — the sentimentality of the counter-culture. They mix frighteningly well: for the counter-culture violence is romantic and shock is beautiful, because extremes of feeling and lack of control are what one takes drugs for. What has been happening, I think, is that the counterculture has begun to look for the equivalent of a drug trip in its theatrical experiences. I think it still responds to non-head movies if there’s a possibility of direct identification with the characters, but increasingly movies appear to be valued only for their intensity. In the Arts and Leisure section of the Sunday Times, which has become a gathering place for euphoric critics, one can see that even the critical prose attempts to evoke psychedelic experience: “At moments [Ken] Russell achieves a kind of cinematic synesthesia, a dizzying, disorienting experience in which all senses — visual, aural, even tactile — seem to blur,” and so on. The worst blows to the art of motion pictures in the past have come from the businessmen who primed everything for the tastes of the conformist mass audience; the worst blows now (and maybe not just to films) could come from the businessmen priming everything for the counter-culture — if the biggest successes turn out to be head movies. (El Topo is being distributed by the manager of three of the Beatles.) Head movies don’t have to be works of art — they just have to be sensational. For heads, there appears to be no difference.

The New Yorker, November 20, 1971 P. 212

1 thought on “El Topo (1970) | Review by Pauline Kael”

Thank you so much for uploading this!!!!!