by Robert L. Carringer

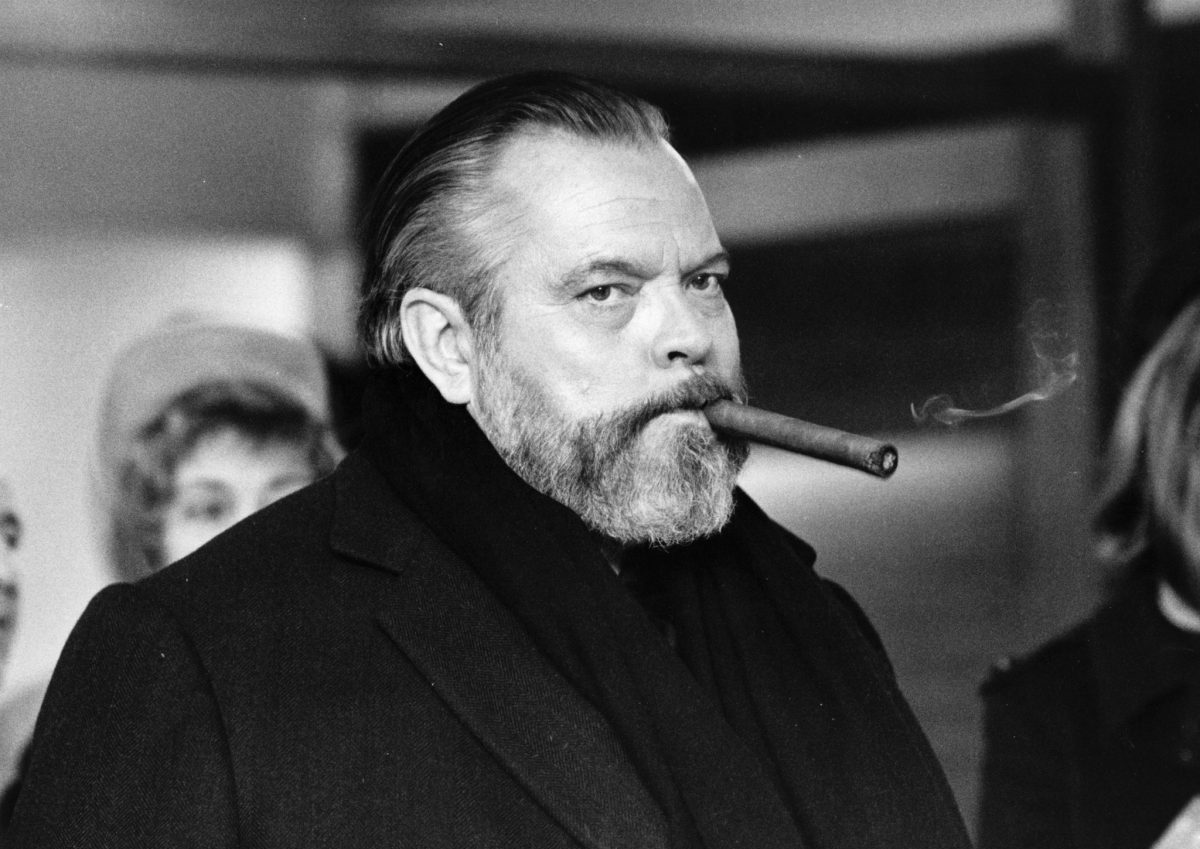

In 1972, when a group of prominent film critics were asked to list the greatest directors and the greatest films, Orson Welles and Citizen Kane both came in first. This result reflected a consensus that had been building for two decades, but it may still have raised some eyebrows among those who thought they saw a steadier and surer career in, say, Bergman’s, Hitchcock’s, Chaplin’s, Renoir’s, or Buñuel’s. Those reputations are all based on sustained output spanning several decades and a solid core of recognized masterworks. Welles, on the other hand, has made one undisputed masterwork in an extremely uneven assortment of about a dozen films. One widely held view, in fact, is that he is a first-film director whose subsequent career has been a perpetual falling-off. Ideological considerations have undoubtedly figured into the making of his enormous current reputation. It may have been the idea of Welles as much as his films that attracted the young Frenchmen who idolized and identified with him and laid the foundation of that reputation. (The dream of all young filmmakers, François Truffaut once guessed, is “to shoot Citizen Kane at twenty-five” — about the age he and several of his New Wave compatriots were when they made their auspicious debuts.) Film history has also been unusually kind to directors like von Stroheim and Welles who went up against Hollywood and lost. But even if such props were taken away, the essential Wellesian reputation would probably still hold firm — though it would be based on different considerations from those applied to most directors of feature films. In some respects Welles’s approach to the medium resembles that of experimental filmmakers like Maya Deren or Jordan Belson more than it resembles Bergman’s. His primary impulse has always been to discover ways of expanding the cinema’s forms and techniques. His overriding concern has been with visual effect, sometimes even to the detriment of dramatic values. This trait has limited the appeal of his films, but he has never allowed it to be compromised, not even on his most routine assignments. Every Welles film is in effect an attempt at redefinition of the medium, a challenge to the audience to reconsider its assumptions about what a cinematic “performance” ought to be. To watch one of his films is to participate in the sheer excitement of discovering the possibilities of the filmmaking medium. To be sure, he can often seem to be nothing more than a magician playing with a bag of tricks, but in the best parts of his films Welles can be the most visually exciting of all directors.

Welles’s films usually revolve around a character played by the director himself. Most often they deal with the defeat, decline, or fall of a powerful figure. His enemy may be jealousy, selfishness, ambition or just time. Most characteristically, perhaps, it is his own corrupting idealism — an exalted self-image become mere egomania, or moral fervor in pursuit of a lofty aim shaded gradually into moral taint. But despite their tragic themes, Welles’s films strike many people as emotionally cold, even abrasive. This effect is probably due in large part to the self-consciousness of his stylistic techniques. The Hollywood system fostered a naturalness of style (if not always of content) that made for the greatest degree of storytelling efficiency and clarity. It consisted especially in certain understated and unobtrusive camera setups (like fixed eye-level camera takes) and patterns of editing (like careful attention to spatial orientation and rhythmic intercutting within a master scene). Obtrusive camera devices and editing that violated predictable patterns were usually reserved for special dramatic effects or conventional segments like montages. Howard Hawks, one of the masters of the Hollywood plain style, has said: “If you’re not good enough to tell a story without having flashbacks, why the hell do you try to tell them? Oh, I think some extraordinarily good writer can figure out some way of telling a story in flashbacks, but I hate them. Just like I hate screwed-up camera angles. I like to tell it with a simple scene. I don’t want you to be conscious that this is dramatic, because it throws it all off.”1

Welles strives for the opposite effect. Devices that draw attention to the medium and the act of filming are the basis of his technique. He constantly approaches his material from odd or unexpected angles, and prefers single long takes to intercutting. He rarely uses that most hallowed of Hollywood studio devices, the close-up, except to emphasize grotesquerie. He stages long and elaborate moving shots. His editing is elliptical — that is, he omits shots that would be expected in a conventional segment of dramatic action, and he cuts abruptly from one setting to another. And he uses, and permits his actors to use, heavy gestures and acting mannerisms that are unusual in films made for commercial release.

Welles’s pre-film background was in theater and radio. He had been involved in stage production and acting from a very early age; by his twenty-first birthday he had already made a reputation as the promising young genius of American theater. In the 1930s with actor-producer John Houseman he founded the Mercury Theatre, which specialized in innovative productions of Shakespeare and the classics. His first love in theater had always been Shakespeare. One reason he went to Hollywood, in fact, was to finance an expensive Mercury Theatre anthology production based on several Shakespeare history plays. But it was through radio work that he first gained national attention. His fortissimo style and voice made him a natural for radio drama. He had become involved in radio acting with the March of Time series in 1934, and for a time he was the voice of Lamont Cranston in the popular crime series The Shadow. Between the summer of 1938 and the spring of 1940 he and the Mercury actors broadcast radio adaptations of numerous literary and popular classics. The program that brought them notoriety was H. G. Wells’s science fiction classic The War of the Worlds, which was updated and broadcast as if an invasion from Mars was in progress in the United States. There was widespread panic, and the uproar caused by the incident lasted for months.

The sensational publicity of The War of the Worlds broadcast and Welles’s reputation as boy wonder of the theater enabled him to get an unprecedented Hollywood contract. A feature film is first and foremost a financial investment. In Hollywood, an executive was assigned to every production and given full authority over it; his job was to protect the studio’s investment. The best protection, according to standard producer mentality, was entertainment safe enough not to offend any large segment of the potential audience. Welles’s contract broke with this standard practice, guaranteeing him control over a project once the studio had given its initial go-ahead. (This freedom extended to the crucial editing phase. Many Hollywood directors shot their films without interference, but did not have authority over the final content.)

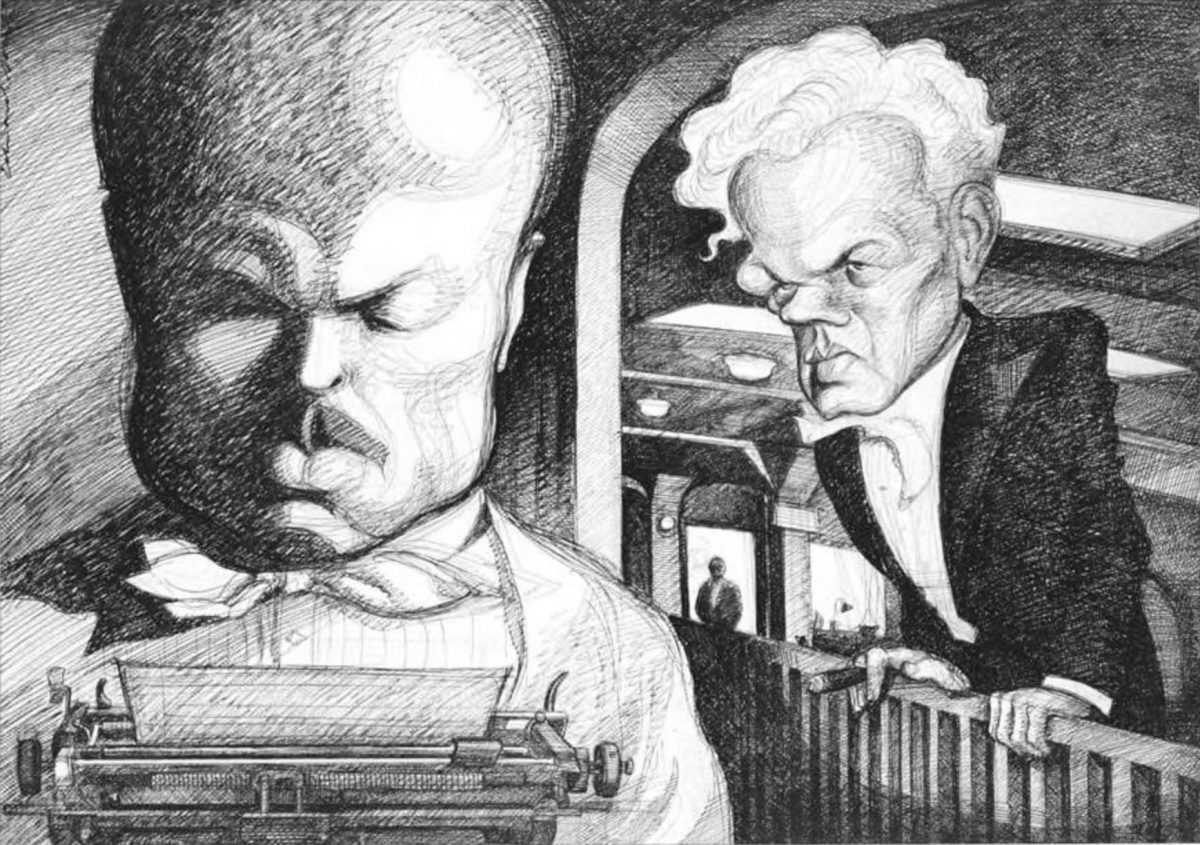

Citizen Kane originated in discussions Welles had with his screenwriter, Herman Mankiewicz, and others. “Tycoon biography,” the genre to which it belongs, is a perennial American form. It flourished as both fiction and nonfiction in the second half of the nineteenth century and was the basis for some of the best work of three generations of American writers. Generally dormant as a novel form after F. Scott Fitzgerald, it continued to flourish in the American film. Actor Edward Arnold was the archetypal tycoon of the movies, in films like Diamond Jim (1935, about Diamond Jim Brady), Sutter’s Gold (1936, about John Sutter and the California Gold Rush), Come and Get It (1936, from Edna Ferber’s novel about a timber baron), John Meade’s Woman (1937, another timber man), and The Toast of New York (1937, about Jim Fisk). There were even flashback tycoon biographies before Citizen Kane, most notably The Power and the Glory (1933, script by Preston Sturges), a story of a railroad magnate with several striking points of resemblance to Welles’s film. Herman Mankiewicz knew a great deal about tycoon legends. He had written the script for John Meade’s Woman, and he knew literary classics of the type like Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby. He also knew a great deal about William Randolph Hearst; he and his wife had been frequent guests at Hearst’s, and he did considerable research on Hearst in preparation for the script. While Welles stayed behind in Hollywood, Mankiewicz went into seclusion miles away to write the script.

A close comparison of Mankiewicz’s early script, called simply American, with biographies of Hearst will show that most of it is a reworking of material from Hearst’s life. (Even the title is probably an ironic allusion to Hearst’s habit of attaching the label “American” to himself and many of his enterprises.) As the script later went through successive drafts back in Hollywood, Charles Foster Kane gradually evolved into a kind of composite of the American magnate as he has traditionally been depicted in American novels and films. But enough of the “Hearst material” survived to betray the ultimate model for Kane. Hearst in his mid-twenties had selected a faltering newspaper out of a large financial empire practically at his disposal and, through a combination of charlatanism and social outrage, built a great publishing empire. Hearst had crusaded for American entry into the Spanish-American War, and had wired his correspondent in Havana, Frederic Remington, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” Hearst was a compulsive collector of statues and art objects. Hearst built a vast estate at San Simeon in California, where he lived with his show business mistress and put on elaborate entertainments for his friends.

Emphasis on directors in recent writing on film has tended to obscure the collaborative nature of the filmmaking enterprise. A director oversees all the phases of production and guides and shapes the elements of collaboration into images and continuity, but the quality of the finished product is only as good as the quality of its collaborators. Welles was fortunate in having some of Hollywood’s best talent working with him on Citizen Kane. Mankiewicz, Hollywood’s reigning wit, was also one of its most durable screenwriters. He had been in Hollywood since the mid-1920s, and though his list of screen credits is not particularly distinctive, his contributions of workable bits and pieces to the scripts of others are probably enormous. American is a rather pale rehearsal of what would eventuate in Citizen Kane. But American had Rosebud, the newsreel, the multiple-testimony form, and the principal characters who are in the film — material “sufficiently complex,” as Charles Higham put it, “to form the basis of a masterpiece.” Bernard Herrmann wrote, orchestrated, and conducted the film’s rich musical score. An accomplished young classical composer, Herrmann had worked with the Mercury Theatre before, scoring radio broadcasts. He wrote the music for Citizen Kane, his first film, “reel by reel, as it was being shot and cut,” instead of following the usual practice of working from a completed film. “In this way,” he said, “I had a sense of the picture being built, and of my own music being a part of that building.” (There is a lengthy description of the film’s music in Higham’s Films of Orson Welles, pp. 14-16.) He was nominated for two Academy Awards that first year in Hollywood (for Citizen Kane and for All That Money Can Buy, which won), and he went on to write some of the best music in films (most notably for Hitchcock) while still pursuing an independent career as composer and conductor.

Gregg Toland, generally regarded as Hollywood’s greatest cinematographer, was the most important influence on the film’s visual appearance. Certain kinds of shots in Citizen Kane suggest earlier work of Toland’s — like comer compositions with a character in off-profile at the side of the screen (see Citizen Kane Book, pp. 222-23 in the Little, Brown edition, or p. 241 in the Bantam edition), and dark interiors with looming figures partly or all in shadows (pp. 268, 282, 287 or 277, 289, 291). The dark, brooding ambience of Citizen Kane and its harsh, expressionistic lighting are also reminiscent of Toland’s earlier work, such as for the Gothic horror thriller Mad Love (1935), or the moody adaptations of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1939) by William Wyler, and Eugene O’Neill’s The Long Voyage Home (1940) by John Ford. Toland devised the means for Welles to break a number of filmmaking conventions in order to achieve the dramatic effects he wanted. Ceilings were used on sets, allowing shots upward from floor level. Flashy new transitional devices were used to link one shot to another. Scenes were played in continuous camera takes with no close-ups or other editing. This was made possible by Toland’s most important contribution to the film, the extreme depth of field he created in some of the shots. Depth of field is the distance toward and away from the camera within which objects appear in sharp focus. (Everything outside this field is blurred or in soft focus.) Because extreme depth of field requires a small camera opening, and hence unusually great amounts of light, it was not in common use at the time of Citizen Kane. By using special lights and lenses and superfast film stock, Toland was able to produce a depth of field from as close to the camera as eighteen inches to as far away as several hundred feet. This is a fundamental innovation in filmmaking. Because of the limited focus problem, the standard practice before Citizen Kane was to break dramatic space into centers of interest by means of editing. Extreme depth of field makes this practice unnecessary, because it allows the dramatic center to shift within a continuous image.

Citizen Kane is sometimes called the film that revolutionized Hollywood. But like many revolutionary works, Citizen Kane is in large part just a striking new combination of already established practices and materials. The images and plot motifs of the film are a joining together of the dark energies of the German horror film tradition with the light energies of the American success tradition. (If the lighting and Kane castle and the secret-of-the-old-dark-house motif seem displacements from Gothic horror thrillers, the projection room sequence makes Rosebud sound like the “Hey, let’s put on a show!” gimmick of popular musicals.) The story of Kane is part contemporary headline, part tradition; though the original model was Hearst, the completed portrait is a composite that includes many fragments from tycoon myths and legends and many elements of stock characterization in stories of the tycoon figure as representative American. The storytelling style of the film is a successful fusion of the flashier devices of 1930s films, and techniques adapted from radio, theater, and prose narrative. There is probably not a single device in Citizen Kane that cannot be found in earlier films, but Citizen Kane synthesizes elements of various traditions in a totally original way.

Despite considerable publicity over the connection with Hearst and the potential succès de scandale, Citizen Kane did not live up to expectations at the box office. If it had made a lot of money, Welles’s position in Hollywood would probably have been secure. And that would have had advantages: Hollywood may be stars and tinsel and the producer mentality, but it is also the center of the world’s greatest concentration of filmmaking resources, and it has always set the highest technical filmmaking standards in the world. What happened to Welles after Citizen Kane is — depending on one’s point of view — either one of film history’s great tragedies (because there might have been more Citizen Kanes, and Welles might have been a good influence on Hollywood) or one of its most fortunate accidents (because he got out in time to save his artistic integrity). His second film project was an adaptation of a novel by Indiana writer Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Amber sons. Immediately after shooting was completed, Welles went off to South America on another project, leaving the film to be edited by others. After a version edited according to his close instructions got cool preview reactions, a massive overhaul was performed, resulting in a version missing almost an hour of the original footage. The reediting of The Magnificent Amber sons is the crucial turning point; it signaled the end of his clout within the Hollywood system. Not long after, when there was a change in management at RKO Studios, his contract was abruptly cancelled and the Mercury Theatre company was ordered to vacate the studio lot. Several other factors had also contributed to the early termination of the most auspicious beginning in American film. The truncated Ambersons looked to be a loser and was released on the lower half of a double bill with Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost. Welles had left the country with a third film still in production. Early footage from the South American project did not seem promising, and publicity continued to flow back about Welles’s “antics,” so studio support of this project was withdrawn. Now he was tagged with such labels as extravagant, undependable, and bad box office. In just two years Broadway’s boy wonder had become Hollywood’s most eminent persona non grata. When he did work in Hollywood again, it was to be on minor assignments at second- or lower-rank studios, usually through the benevolence of a producer looking for a “class” project to increase his prestige.

The Magnificent Ambersons (novel, 1918; film, 1942) is the story of the decline of nineteenth-century midwestern gentry as their town grows into the modem industrial age. Like Citizen Kane, it is a story of nostalgia for a vanished American past (represented by the Ambersons) and selfish destructiveness (an Amberson heir comes between his widowed mother and the man she loves). It is unusual among Welles’s films for its placidity and quiet lyricism, for its faithfulness to its source, and for the absence of Welles as actor. It also has storytelling flaws that will reappear to greater or lesser degree in most of his subsequent films (though, in fairness to Welles, because of the reediting it is difficult to say how much of this is his fault) : the characters are “underdramatized” — things are said or suggested about them but never convincingly demonstrated; the structure is episodic; there are gaps in continuity; the narration is sometimes difficult to understand. The Stranger (1946), made for producer Sam Spiegel, with Welles playing a former Nazi posing as a schoolteacher in a New England town, is his least characteristic film. Macbeth (1948), made on a shoestring budget at a studio usually associated with low-budget Westerns and serials, is one of his experimental Shakespeare productions, in a class with an earlier voodoo stage version of the same play; it has intriguing Wellesian interpolations and effects, but not much else. His most interesting picture in these years is a murder thriller, The Lady from Shanghai, made in 1946 for Columbia Pictures but not released until 1948, and starring Welles and his one-time wife, glamor girl Rita Hayworth. Welles is an Irish sailor duped into a murder set-up by a beautiful, rich blonde on the pretext of rescuing her from danger. Beyond that, the plot is an incredible tangle of complications that defies summation. In its complicated murder intrigue, generally slimy and insidious characters, and intimations of aberrant and possibly obscene goings-on, Lady from Shanghai resembles film noir, a crime genre that flourished in Hollywood in the 1940s and included such classics as The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. Many major directors worked in the genre at one time or another. One source of its appeal was the freedom of its subject matter. Within the stylization of melodrama film noir depicted a brutal and cynical vision of America that would never have been tolerated in the studios’ more respectable product. And the unfathomable plots of film noir stood on its head an inviolate Hollywood rule that everything be immediately clear to a twelve-year-old. Welles’s venture into the genre is delightfully tongue-in-cheek, full of mannered camera angles, overlapping dialogue, and other deliberate violations of studio practices. The long trial sequence is a wry satire on courtroom drama. The film’s finale, an elaborate shoot-out in a hall of mirrors, is one of the most exciting sequences ever put on film.

Welles became involved in a tax dispute with the Internal Revenue Service in the late 1940s over losses on one of his costly stage productions, and he has spent most of his time since then abroad. He has returned to this country frequently for stage and television work and to act in films by other directors, but during this period he made only one film in Hollywood, Touch of Evil (1958). His main directorial energies have gone instead into his international ventures — independently financed films made in Europe according to his conceptions and under his control. These include two Shakespearean works, Othello (1952) and Falstaff (1966); Mr. Arkadin (1955), a pallid reworking of Citizen Kane material adapted from a novel attributed to Welles; an adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial (1962); and Immortal Story (1968, for French television), based on a novella by Isak Dinesen, a philosophical fable about the making of fictions and their relationship to fact. (Several other projects, most notably a modernization of Don Quixote begun in 1955, are uncompleted or unreleased.) Each of Welles’s international ventures has had dazzling shots and brilliant sequences, but most have also had serious flaws. Generally they have been underfinanced; for this and other reasons there have frequently been interrupted shooting schedules and other production problems, and the laboratory work has been inferior to most films made for theatrical release. These problems show up in defects in the sound tracks and continuity of the films, and the overall patchwork quality that characterizes portions of some of them. When other handicaps are added, such as Welles’s fondness for narrating and dubbing speaking parts in a sonorous mumble, and his tendency to allude to traits or motives rather than convincingly dramatizing them, it is not hard to see why these films have reached such small audiences and have had such mixed critical reactions.

The reputation of Touch of Evil has risen dramatically in recent years; there are many who now regard it as one of Welles’s two or three most important films. On the surface it is a compendium of Hollywood plot and casting clichés. Welles plays Hank Quinlan, a police chief in a California town on the Mexico border who plants evidence to get convictions. There is a faithful partner whose life Quinlan once saved, and Charlton Heston, in mustache and Mantan, is Vargas, a Mexican narcotics official who catches Quinlan in the act. Janet Leigh plays Vargas’s virginal bride; Marlene Dietrich also appears, exuding old- world corruption, as keeper of a brothel. The script is filled with lines like “He was some kind of a man!” (Dietrich’s epitaph for Quinlan), and “It’s over, Susie, I’m taking you home!” (Heston to Leigh after she has survived a doping, a murder frame-up, and, possibly, a rape). But as with Lady from Shanghai, the appearance of banality is not the thing itself. Touch of Evil is one of the most visually inventive films ever to come out of Hollywood. It has all the dreadful and profoundly disturbing poetry of a nightmare, and Hank Quinlan may be Welles’s most deeply felt character. One of the ironies of Welles’s directing career is that he has usually been at his best working with such material. When he has been on his own in Europe, he has invariably selected intellectually respectable source material, and the European films have usually had defects far more serious than their technical ones. They are sententious, the actors are terribly overindulged, and there is a heavy air of self-satisfaction about them. Hollywood producers and popular story forms, on the other hand, have forced Welles to work by indirection. The result has been the comic irreverence, the genuine visual inventiveness, and the subversive vision of films like Citizen Kane, The Lady from Shanghai, and Touch of Evil. The Trial, Welles’s next film after Touch of Evil, was also concerned with the terrors of police mentality run rampant. It was a loose but not altogether unfaithful adaptation of a modern literary classic. But it is Touch of Evil that continually yields up unsuspected ambiguities and visual riches, while The Trial continues to strike many viewers as an overstuffed failure. Welles confided once that he had a trunkful of books and scripts he would like to film; one of his defenders speculated that in that trunk not one thriller would be found. But for all the difference in levels of respectability between The Trial and Touch of Evil, it may well be — to adapt a famous adage of Pauline Kael’s — that there is more art in the spectacular twenty final minutes of the Hollywood thriller than in the entire two long hours of the other film.

People not involved in the study of film are often surprised to learn that Citizen Kane is so highly regarded. The rapid pace and newspaper montages and the Rosebud business — all that looks so typically Hollywood. Especially Rosebud: the apparent conclusion that premature loss of home and mamma’s arms scarred Kane for life seems like such a pat case of Hollywood oversimplification, amateur psychologizing on the order of what one finds in, say, Hitchcock’s Spellbound. (“Dollar book Freud,” Welles calls it.) But that view belongs to the old days, when films appeared briefly, were seen once, and then vanished to make way for next year’s model. With the recent rise of serious interest in film, there has been a general discovery that films can have the same complexity of structure and density of theme as novels and plays — and a related discovery that they may not really say what they first seemed to say. If Rosebud is the final answer in Citizen Kane to the mystery of its subject, why Thompson’s disclaimer that Rosebud wouldn’t have explained anything? Where in the film do we see the childhood innocence and maternal security Rosebud is supposed to represent? Is Rosebud supposed to be the piece that will complete the puzzle, or just another missing piece? If the latter, what is the film’s solution to the mystery of Kane? When examined closely, practically every sequence turns up questions and problems of this sort. According to Welles, the film is supposed to work in just this way — by leading us into believing something at one point which is undercut somewhere else. Underneath the breezy, self-confident surface manner of Citizen Kane is an intricate and carefully contrived structure. As we begin to look into its unsuspected complexities, our point of departure probably ought to be not Rosebud, but Welles’s own statement about what he intended in the film:

Citizen Kane is the story of a search by a man named Thompson, the editor of a news digest (similar to the March of Time), for the meaning of Kane’s dying words. He hopes they’ll give the short the angle it needs. He decides that a man’s dying words ought to explain his life. Maybe they do. He never discovers what Kane’s mean, but the audience does. His researches take him to five people who know Kane well — people who liked him or loved him or hated his guts. They tell five different stories, each biased, so that the truth about Kane, like the truth about any man, can only be calculated, by the sum of everything that has been said about him.

Kane, we are told, loved only his mother — only his newspaper — only his second wife — only himself. Maybe he loved all of these, or none. It is for the audience to judge. Kane was selfish and selfless, an idealist, a scoundrel, a very big man and a very little one. It depends on who’s talking about him. He is never judged with the objectivity of an author, and the point of the picture is not so much the solution of the problem as its presentation.2

Notes

1. Film Comment, May/June 1974, p. 47.

2. Focus on “Citizen Kane ” p. 68.

SEQUENCE OUTLINE

Deathbed sequence

“No Trespassing” sign. Xanadu in the distance. A series of views over the deserted grounds. A lighted window in a wing of the castle.

Whirling snow. A round glass paperweight with a winter scene inside. Kane’s lips forming a word, “Rosebud.” The paperweight falls from Kane’s hands and smashes to pieces on the mable floor. A nurse enters; she draws a bedsheet over Kane’s body.

Newsreel sequence

“News on the March,” a newsreel obituary/biography of Charles Foster Kane in the style of March of Time. Xanadu, Kane’s vast estate on a Florida mountaintop, “since the Pyramids … the costliest monument a man has built to himself.” A montage of newspaper headlines announcing Kane’s death. The Kane fortune and its origins. The public Kane, a figure of controversy — a Communist? a Fascist? a true American? Kane’s private life — married to a president’s niece, divorced and remarried to a singer; Susan Kane’s opera career, expose of the “love nest,” and Kane’s defeat at the polls. Collapse of the empire during the Depression. The waning of Kane’s influence. Kane alone and aloof toward the end in his “never finished, already decaying pleasure palace.”

Projection room sequence

Rawlston, the boss, tells Thompson, who put together the newsreel, that it’s a good job, but it lacks a personal, human interest angle. Kane’s dying word might provide it. Thompson is to hold up release of the newsreel while he tries to find out who or what Rosebud is.

First visit to Susan Alexander Kane

Thompson goes to see Susan at “El Rancho,” a nightclub in Atlantic City where she performs. She is despondent and refuses to talk. The headwaiter says she told him she never heard of Rosebud.

The memoirs of Walter Parks Thatcher

Thompson visits the imposing Thatcher Memorial Library. A sour and officious custodian permits him to inspect the portions of Thatcher’s unpublished memoirs dealing with Kane.

In 1871 Kane’s mother made an agreement whereby Thatcher and the bank became young Kane’s financial and personal guardian, and

Kane was sent away with Thatcher. At twenty-one, when Kane was to assume responsibility and control of his vast fortune, he wrote Thatcher to say he wanted to run a newspaper — he thought it “would be fun.” Kane used his newspaper to campaign against Thatcher and Wall Street financial combines. But he was a poor manager of his finances, and during the Depression he had to give up control of his newspapers to Thatcher.

Bernstein’s story

Thompson visits Bernstein, Kane’s former general manager. (Bernstein has his own Rosebud — an evanescent girl-in-white he caught a glimpse of fifty years before and thinks of practically every day.)

Bernstein tells of Kane’s taking over the Inquirer, cleaning house, and becoming a crusading publisher, complete with a high-minded “Declaration of Principles.” In six years the Inquirer went from a circulation of 26,000 to almost 700,000, highest in New York. (A party was given to celebrate the paper’s surpassing of its rival, the Chronicle.) Kane returned from one of his “collecting” vacations in Europe to announce his engagement to Emily Monroe Norton, niece of the president.

Leland’s story

Thompson visits Jedediah Leland, Kane’s onetime dramatic critic and longtime closest friend, in a sanitarium. (Leland says he read about Rosebud, but never believed anything he saw in the Inquirer.)

Leland tells of the progressive deterioration of Kane’s first marriage, his affair with Susan, the exposure of their “love nest” that cost Kane the governorship, and Susan’s disastrous Chicago debut. Leland started a negative review but got too drunk to complete it; Kane finished it and had it printed under Leland’s byline. Leland was fired.

Susan Alexander Kane’s story

Thompson returns to Susan’s nightclub. Susan tells him Kane pushed her into the opera career and kept driving her until she couldn’t take it any more. (We see her singing lessons, the Chicago debut from her point of view, and a montage of headlines in Kane papers about her subsequent performances.) After her attempted suicide, Susan gave up her career and retired to Xanadu with Kane. (In the cavernous great hall of Xanadu Susan protests to Kane that it’s lonely and there’s nothing to do. She diverts herself with jigsaw puzzles. Kane takes her and the guests on an elaborate “picnic” in the Everglades.) Kane was too selfish and overbearing; Susan finally left him.

Xanadu sequence

For a thousand dollars, Raymond, Kane’s steward at Xanadu, tells Thompson what he knows.

Kane smashed up Susan’s room after she left and picked up the glass paperweight and said “Rosebud.” (When Kane leaves her room and walks down a corridor between two mirrors, we see receding reflections of his image.)

Kane’s possessions are being inventoried as Thompson gets ready to leave. A companion asks him about Rosebud, and he replies that it “wouldn’t have explained anything” even if he had found it. “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life.”

The camera moves up and out and over Kane’s scattered possessions. Finally it moves in and picks out one object from the rest, a sled. A workman tosses the sled into a furnace. As it begins to burn, we can see a small rosebud painted on it; above that the word is written out.

Exterior shot of Xanadu with smoke rising from the chimney. Back down to the starting point, the “No Trespassing” sign.

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Bogdanovich, Peter. “The Kane Mutiny.” Esquire, October 1972, pp. 99-105 +. Recent studies by Charles Higham, Pauline Kael, and others have not been very complimentary to Welles. Higham characterizes him as disorganized, irresponsible, and unable to complete many of the projects he undertakes. Pauline Kael represents him as a colossal egotist trying to steal credit for the work of others. Director Peter Bogdanovich (Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc?) has had a lengthy reply in preparation for several years. The would-be Boswell to Welles’s Johnson, Bogdanovich has had Welles’s cooperation in the project and full access to his papers. A book was announced for publication as early as 1971 but has not yet appeared. Indications are that the Citizen Kane portion will be substantially the material that appeared in Esquire. In the article he attempts to refute Pauline Kael’s charges that Herman Mankiewicz is the film’s real author and Gregg Toland its visual genius.

The Citizen Kane Book. Boston: Little, Brown, 1971; Bantam paperback, 1974. This volume contains the final shooting script of the film, for which Welles and Herman Mankiewicz shared screen credit; a cutting continuity (that is, a detailed stenographic transcription of the completed film); and “Raising Kane,” Pauline Kael’s massive background study which outlines the various traditions in American films of the thirties that influenced Citizen Kane. (One of her principal arguments is that virtually total credit for the script ought to go to Mankiewicz. She clearly overstates the case, but “Raising Kane” has helped to create a new awareness of the screenwriter’s importance to a film.) Indispensable.

Cobos, Juan; Rubio, Miguel; and Pruneda, Jose A. “A Trip to Don Quixoteland: Conversations with Orson Welles.” Cahiers du cinema in English 5 (1966), 34-47. Reprinted in Interviews with Film Directors, ed. Andrew Sarris (Bobbs-Merrill, 1967; Avon paperback 1969), and (with portions deleted) in Focus on “Citizen Kane.” In the absence of Bogdanovich’s promised study, the fullest record of the director’s views.

Cowie, Peter. A Ribbon of Dreams: The Cinema of Orson Welles. New York: A. S. Barnes; London, Tantivy, 1973. An updated version of the author’s Cinema of Orson Welles (1965). The well-balanced chapter on Citizen Kane is one of the best all-around introductions to the film. (It is reprinted in Focus on “Citizen Kane.”) Overall, Cowie is extremely charitable to Welles, and his tone is next to idolatrous. The international ventures he rates high — The Trial he considers next in importance to Citizen Kane — and he disparages the Hollywood pictures after Magnificent Ambersons. (Other critics, Andrew Sarris and Charles Higham among them, have held just the opposite.) Most of the chapters after the one on Citizen Kane are thin.

Focus on “Citizen Kane.” Ed. Ronald Gottesman. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971. A collection of critical commentary on the film, with a miscellany of other material (the interview cited above, an important general essay by William Johnson, a plot synopsis) and a useful annotated bibliography. A companion title, Focus on Orson Welles} is in preparation by the same editor.

Higham, Charles. The Films of Orson Welles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970. The long chapter on Citizen Kane contains a wealth of background and production information not available elsewhere. Welles partisans have attacked this book as malicious and inaccurate, but there is not enough information available yet to judge. Writing on film at the moment is heavily dependent on oral testimonies, and many of the participants and witnesses are trying to enhance their own reputations or settle old scores.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. Cinema One. New York: Viking, 1972. The chapter on Citizen Kane is the best recent critical study. McBride has paid closer attention to the film’s ambiguities than any other critic.

Robert L. Carringer teaches literature, film, and interdisciplinary studies courses at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He writes in all three areas and is currently completing a series of essays on American films and the American narrative tradition. His study of Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove was printed in the JAE^ January 1974 issue.

Source: Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 9, No. 2, Special Issue: Film IV: Eight Study Guides (Apr., 1975), pp. 32-49. Published by: University of Illinois Press