FASHION

Originally adopted to tackle lice and hide baldness, wigs became invaluable allies in concealing the ravages of syphilis that swept through 16th-century Europe. They fell from grace along with the heads of the nobles who wore them, as the French Revolution swept through.

by Chris Montanelli

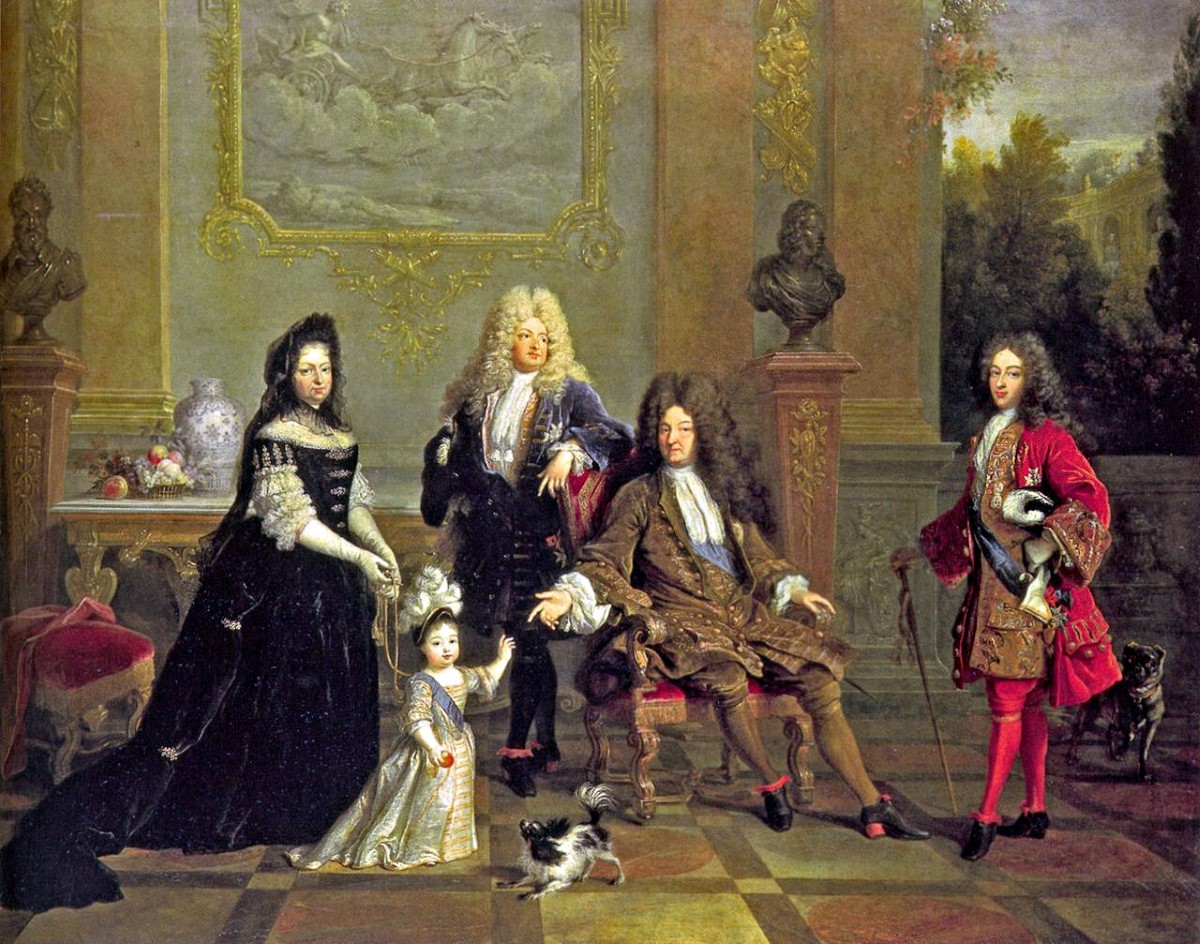

The trend of donning wigs was kick-started in the 17th century by King Louis XIII of France who, at the tender age of 17, sought to disguise his premature balding, quickly becoming a trendsetter followed by his cousin, King Charles II of England. Inspired by their royal endorsements, wigs swiftly became a status symbol for aristocrats across Europe, elevating a practice that, truth be told, had been around for quite some time. Sporting false hair—where the deluxe versions demanded human hair, while horse, goat, or yak hair sufficed for the budget-conscious—was primarily a tactic to combat pediculosis, a real scourge facilitated by close living quarters and poor hygiene: lice feed on the blood of their host and need direct scalp contact to thrive; away from the human body, they don’t survive long. Wigs were often dusted with finely ground starch or flour, giving them their characteristic greyish-white hue and to mask the foul odor of seldom-washed false hair, fragrant essences of lavender or orange were mixed into the powder.

This powdered wig fad persisted for nearly two centuries, providing nobles—women, in particular—a canvas to flaunt elaborate and hefty “hair sculptures.” Queen Marie Antoinette of France was a fervent enthusiast, so much so that she enlisted Léonard-Alexis Autié as her personal hairdresser and designer. In 1774, he crafted the “pouf” hairstyle: a towering structure of light metal and padded gauze upon which both real and fake hair was layered, pomaded, powdered, and adorned with curls, ostrich feathers, ribbons, and precious stones. Marie Antoinette was delighted, parading ever more intricate hairstyles and quickly setting a trend among court ladies. This sparked a near-grotesque competition, peaking in 1778 when, to commemorate the French aiding American colonies against England, Autié created the “Belle Poule” hairstyle, complete with a model warship, sails, and artillery on top.

However, the popularity of these costly and spectacular wigs wasn’t driven merely by aesthetic whimsy. From the 16th century, Europe was ravaged by syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease causing skin eruptions, blindness, hair loss, and dementia. Wearing a wig could discreetly cover hair loss, a source of shame and embarrassment, while the scented powder helped mask the putrid smell emanating from sores.

Wig fashion sharply declined by the end of the 18th century: in England, when Prime Minister William Pitt imposed a tax on the powder used to dust them in 1795 to prevent flour wastage and raise funds; in France, with the Revolution, which saw them roll alongside the heads of their wearers. Other countries gradually followed suit, and wigs remained a nostalgic attribute for certain “special” professions, such as lawyers and judges, or as a simple aesthetic accessory to keep up with fashion trends or disguise baldness.