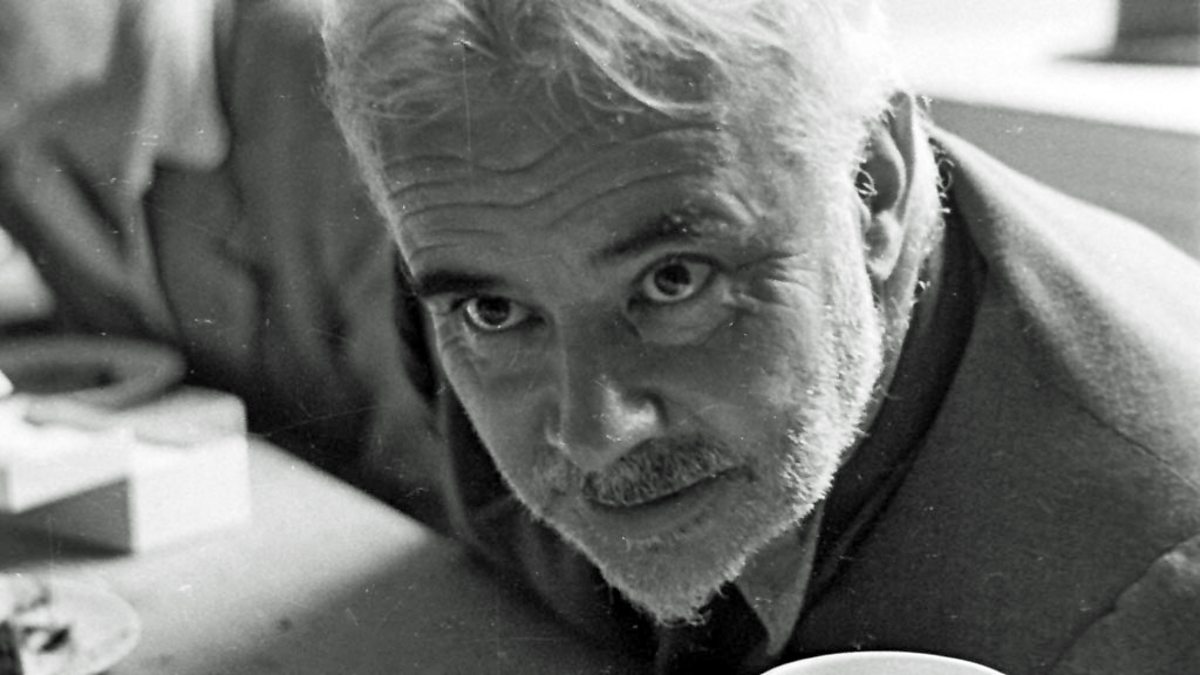

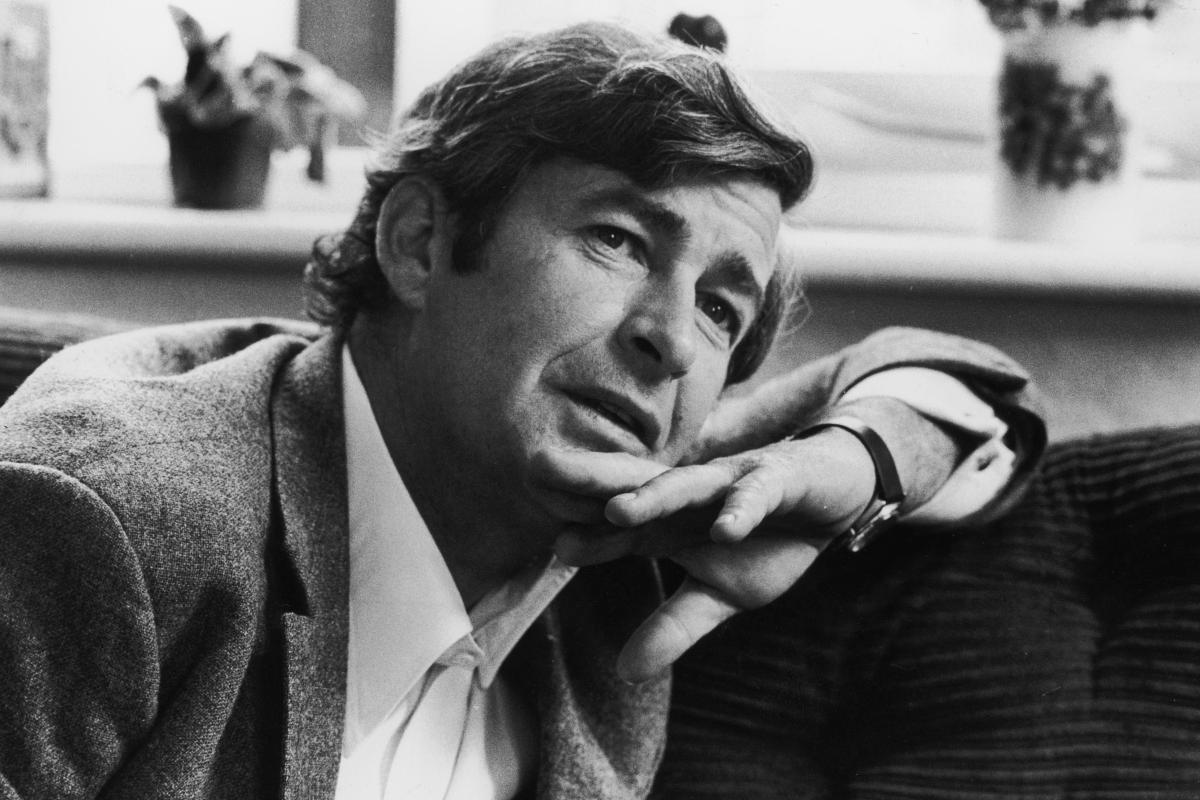

Tony Jones: Good evening and welcome to Q&A. I’m Tony Jones and answering your questions tonight: world renowned evolutionary biologist and author of The God Delusion Richard Dawkins and – wait a minute. Hold your applause just for a moment. And Australia’s most senior Catholic Church man, the Archbishop of Sydney Cardinal George Pell. Please welcome our special guests.

Okay. Q&A is live from 9.35 Eastern Time and simulcast on News 24 and News Radio. Go to our website to send a question or join the Twitter conversation using the hash tag on your screen and stay tuned for the chance to join QandaVote. You can register on your smart phone or smart device at the address on the screen. The address is qanda.vote – qandavote.tv, I should say. Our first question tonight comes from Naomi Roseth.

VALUES OF ATHEISM AND FAITH

Naomi Roseth: At Easter Australia’s religious leaders invoke the name of God in order to preach peace, tolerance, political integrity, social and moral fortitude, all obviously positive and worthwhile values. My question is: in what way is the practice of these values dependent on an existing God? Is it possible for an atheist to be a peace loving socially responsible person?

Jones: Richard Dawkins, let’s start with you.

Richard Dawkins: Well, obviously the answer to that question is yes. I mean that could hardly be otherwise. It is true that Christianity has adopted many of the best values of humanity but they don’t belong to Christianity or any other religion. I think it would be very sad if it were true that you really did need religion in order to be good because if you think about it what that would mean would be either that you get your morals and your values from the Bible or the Quran or some other holy book or that you are good only because you’re frightened of God, because you don’t want to go to hell or you do want to go to heaven. Now, as for getting your morals from the Bible, I very sincerely hope nobody does get their morals from the Bible. It’s true that you can find the occasional good verse and the Sermon on the Mount would be one example, but it’s lost amid the awful things that are dotted throughout the Old Testament and actually throughout the New Testament as well because the idea – the fundamental idea of New Testament Christianity, which is that Jesus is the son of God who is redeeming humanity from original sin, the idea that we are born in sin and the only way we can be redeemed from sin is through the death of Jesus, I mean that’s a horrible idea. It’s a horrible idea that God, this paragon of wisdom and knowledge, power, couldn’t think of a better way to forgive us our since sins than to come down to Earth in his alter ego as his son and have himself hideously tortured and executed so that he could forgive himself.

Jones: Okay, let’s go to George Pell on that.

George Pell: Well, there’s quite a few things that might be said. First of all our tradition goes back about 4,000 years so whatever these values are that we’ve taken over, we’ve got to go back a little bit of a distance and it’s interesting to look at Pagan Rome before there was Christian influence. Forty per cent was slaves. Men and women fought one another to the death in, you know, the Circus Maximus or the Colosseum. Women had no rights whatsoever. Infanticide was practiced regularly. The noble families didn’t want baby girls. Christianity changed that. Not perhaps by itself but largely. And the Christian story we’re Christians, we’re New Testament people. There was an evolution in the Old Testament. There are some awful things there. It developed. The notion of God was purified as it went through the Old Testament.

Jones: Can I just interrupt you just to bring you to point of the question, which was really about whether atheists can lead a good life and be good people and socially responsible and so on.

Pell: Yeah, absolutely.

Jones: You accept that?

Pell: Yeah, absolutely. I think it helps to believe in God because – there’s a Polish poet, Milosh, who says that the opium of the people today is the belief that they won’t be judged by God when they die, those who have committed great crimes, done awful things are going to get away with it and that the people who have suffered unjustly, had terrible lives, that’s it.

Jones: Okay, let’s move quickly to our second question. It’s from Clare Bonner.

IS RELIGION A FORCE FOR GOOD

Clare Bonner: Religion is precisely often blamed for being the root of war and conflict but what about all the good it has done for society. God-centred religion has been the birth place of schools, universities, hospitals and countless developments in science. Richard, if you believe the human drive to seek the truth and to constantly improve ourselves is merely a mechanism for survival, then what’s the point and why should I bother?

Dawkins: It’s an astonishing idea to say why should you bother just because we have a scientific understanding of why we’re here. We do have a scientific understanding of why we’re here and we therefore have to make up our own meaning to life. We have to find our own purposes in life, which are not derived directly from our scientific history.

When you say that Christianity has been responsible for a lot of good, including science by the way, which is somewhat ironic, I think that most of the great benefits in humanity, such as the abolition of slavery, such as the emancipation of women, which the Cardinal both – mentioned both of, these have been rung out of our Christian history without much support from Christianity. I, as an atheist, my friends as atheists, lead thoroughly worthwhile lives, in our opinion, because we stand up, look the world in the face, face up to the fact that we are not going to last forever, we have to make the most of the short time that we have on this planet, we have to make this planet as good as we possibly can and try to leave it a better place than we found it.

Jones: Now, to some degree you’ve already answered this but there is a follow-up question. I’m going to go to that now. It’s from Rebekah Ray.

VALUES OF “SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST”?

Rebekah Ray: Okay, my question for you today is: without religion, where is the basis of our values and in time, will we perhaps revert back to Darwin’s idea of survival of the fittest?

Jones: Richard Dawkins, you can answer that and I’ll bring in Cardinal Pell.

Dawkins: I very much hope that we don’t revert to the idea of survival of the fittest in planning our politics and our values and our way of life. I have often said that I am a passionate Darwinian when it comes to explaining why we exist. It’s undoubtedly the reason why we’re here and why all living things are here. But to live our lives in a Darwinian way, to make a society a Darwinian society, that would be a very unpleasant sort of society in which to live. It would be a sort of Thatcherite society and we want to – I mean, in a way, I feel that one of the reasons for learning about Darwinian evolution is as an object lesson in how not to set up our values and social lives.

Jones: George Pell.

Pell: Well, it’s interest because I think in the space of about two minutes, Richard has said two different things, one of which is that science can’t tell us why we’re here and then in the next minute, trying to say that it does.

Dawkins: No. No. I said it can tell us why we’re here.

Pell: It can’t.

Dawkins: Well, I simply contradict you in that case.

Pell: Well, what is the reason that science gives why we’re here? Science tells us how things happen, science tells us nothing about why there was the big bang. Why there is a transition from inanimate matter to living matter. Science is silent on we could solve most of the questions in science and it would leave all the problems of life almost completely untouched. Why be good?

Dawkins: Why be good is a separate question, which I also came to. Why we exist, you’re playing with the word “why” there. Science is working on the problem of the antecedent factors that lead to our existence. Now, “why” in any further sense than that, why in the sense of purpose is, in my opinion, not a meaningful question. You cannot ask a question like “Why down mountains exist?” as though mountains have some kind of purpose. What you can say is what are the causal factors that lead to the existence of mountains and the same with life and the same with the universe. Now, science, over the centuries, has gradually pieced together answers to those questions: “why” in that sense. It’s true that there are still some gaps but surely, Cardinal, you aren’t going to fall for the God of the gaps trap in saying that religion is going to fill in those gaps which science has so far not yet answered.

Pell: No, I’m not going to be diverted at all. I am happy to come back to that.

Jones: We will be coming back to it because I know there are questions that relate to some of the bigger issues you’re talking about but you can respond and then we’ll move onto our next question.

Pell: I hope I’ll be allowed to.

Jones: You certainly will.

Pell: Thanks. It’s part of being human to ask why we exist. Questioning distinguishes us from the animals. To ask why we’re here, I repeat and this is a commonplace in science, science has nothing to say about that. Whatever it might say about mountains, it can’t say what is the purpose of human life and it’s not Maggie Thatcher who was in the epitome or the personification of social Darwinism. It’s Hitler and Stalin.

Dawkins: I have said…

Pell: Because it is the struggle for survival, the strong take what they can and the weak give what they must and there is nothing to restrain them and we have seen that in the two great atheist movements of the last century.

Dawkins: Oh, now that’s ridiculous. This is ridiculous. A most unbiased audience you’ve assembled here by the way. Right, let’s clearly distinguish two things here. First, atheism had nothing to do with Hitler and Stalin. Stalin was an atheist and Hitler was not. It doesn’t matter what they were with respect to atheism, they did their horrible things for entirely different reasons. Now, you are right when you say that aspects of what Hitler tried to do could be regarded as arising out of Darwinian natural selection. That’s exactly why I said that I despise Darwinian natural selection as a motto for how we should live. I tried to say we should not live by Darwinian principles but Darwinian principles explain how we got here and why we exist in the scientific sense. Now, Cardinal, you said it’s part of human nature to want to ask the question why in the sense of purpose. It may very well be part of human nature but that doesn’t make it a valid question. There are all sorts of questions which you can ask.

(Audience laugh)

Dawkins: What’s funny about that? What is funny about that?

Jones: Okay, we’d like the audience not to yell out. If we can do that, that’d be great. We’re going to move on.

Dawkins: I didn’t finish, I’m sorry.

Jones: Okay, well, finish your point.

Dawkins: Okay.

Jones: Because there are lots of questions pertaining this we will be coming back to.

Dawkins: The question why is not necessarily a question that deserves to be answered. There are all sorts of questions that people can ask like “What is the colour of jealousy?” That’s a silly question.

Pell: Exactly.

Dawkins: “Why?” is a silly question. “Why?” is a silly question. You can ask, “What are the factors that led to something coming into existence?” That’s a sensible question. But “What is the purpose universe?” is a silly question. It has no meaning.

Pell: Could I just interpose very briefly.

Jones: Very briefly.

Pell: I think it’s a very poignant and real question to ask, “Why is there suffering?”

Jones: We will be asking that question, believe it or not. This is Q&A. It’s live and interactive. Tonight we’re experimenting with qandavote, a new way for Q&A viewers to share their opinions on the issues we discuss. You can go to the qandavote.tv website on your smart phone, tablet or computer to vote in our very first question and that is: does religious belief make the world a better place? Does religious belief make the world a better place? We’ll report back later on your views. First, let’s move on to our next question for our panel. It comes from Paul Hanrahan.

DAWKINS – ATHEIST OR AGNOSTIC?

Paul Hanrahan: My question is for Richard Dawkins. You’re on the record as saying you can’t prove that God doesn’t exist and you say you’re agnostic rather than atheistic. Why do you appear as the champion of atheism around the world? Why do you accept offers to appear as the champion of atheism and why are you so evangelical in the prosecution of your cause? Isn’t that a touch hypocritical and unscientific?

Jones: Yes, Richard Dawkins, I’m a bit confused about this because you just referred to yourself moments ago as being an atheist and yet, with the Archbishop of Canterbury, you referred to yourself as an agnostic?

Dawkins: In the God Delusion I make a seven-point scale. One is I’m totally confident there is a God. Seven is I’m totally confident there is not a God. Six is to all intents and purposes I’m an atheist. I live my life as though there is no God but any scientist of any sense will not say that they positively can disprove the existence of anything. I cannot disprove the existence of the Easter Bunny and so I am agnostic about the Easter Bunny. It’s in the same respect that I am agnostic about God.

Jones: So what proof, by the way, would change your mind?

Dawkins: That’s a very difficult and interesting question because, I mean, I used to think that if somehow, you know, great big giant 900 foot high Jesus with a voice like Paul Robeson suddenly strode in and said “I exist. Here I am” but even that I actually sometimes wonder whether that would…

Pell: I’d think you were hallucinating.

Dawkins: Exactly. I agree. I agree. I agree.

Jones: Well, can I just put a question to you? Could you ever provide Richard Dawkins with the sort of proof he requires for belief? Scientific proof of the existence of God?

Pell: No, because I think he only accepts proof that is rooted in sense experience. In other words he excludes the world of metaphysics, say the principle of contradiction, and he excludes the possibility of arguments that don’t go against reason but go beyond it. But could I make one little suggestion as to why Richard calls himself an atheist? Because in one of his blogs in 2002, he was discussing whether he’s an agnostic or a non-theist. He said he prefers to use the term atheist because it is more explosive. It’s more dynamic. You can shake people up, whereas if you’re just going around saying you’re an agnostic or a non theist, it’s – these are his own words.

Jones: Well, let’s let Richard Dawkins respond.

Dawkins: I don’t remember saying that. It wouldn’t totally surprise me. It’s…

Pell: It’s in 2002.

Dawkins: It’s an ongoing issue, what’s the best way. There is a problem with the word atheist, especially in America. I don’t know whether it is true in Australia. There is a lovely woman – I am blocking on her name because I am jetlagged. She’s Irish American woman. Anybody help me?

Jones: There are quite a few Irish American women. Sorry about that.

Dawkins: Anyway, I do apologise personally to her for forgetting her name.

Pell: What does she do?

Dawkins: She’s an actress and she did a film on how she escaped from the Roman Catholic Church and it is a very moving film and at the end her mother discovered she was an atheist and her mother phoned her up and said “Well, I don’t mind you not believing in God but an atheist!” Her name is Julia Sweeney. It’s suddenly come back to me. I strongly recommend that. Now, the point is that the word atheist, unlike just not believing in God, has bad connotations and so to some extent people have wished to depart from that and change the name to non theist or secularist or non-believer and I waver back and forth as to what is the best name to use. I sometimes call myself an atheist, sometimes a non theist and sometimes just a non-believer.

Jones: George Pell, can I just come back to you on this question of the existence of God. Why would God randomly decide to provide proof of his existence to a small group of Jews 2,000 years ago and not subsequently provide any proof after that?

Pell: Well, I don’t think there’s ever been any scientific proof. I don’t believe God does anything randomly, although he might set up he might set up a system which works, apparently through, you know, through chance, through random but if you want something done, you’ve got to ask somebody. It’s no good, say, my asking everyone in the congregation will you would do something. Normally you go to a busy person because you know they’ll do it and so for some extraordinary reason God chose the Jews. They weren’t intellectually the equal of either the Egyptians or the…

Jones: Intellectually?

Pell: Intellectually, morally…

Jones: How can you know intellectually?

Pell: Because you see the fruits of their civilisation. Egypt was the great power for thousands of years before Christianity. Persia was a great power, Caldia. The poor – the little Jewish people, they were originally shepherds. They were stuck. They’re still stuck between these great powers.

Jones: But that’s not a reflection of your intellectual capacity, is it, whether or not you’re a shepherd?

Pell: Well, no it’s not but it is a recognition it is a reflection of your intellectual development, be it like many, many people are very, very clever and not highly intellectual but my point is…

Jones: I’m sorry, can I just interrupt? Are you including Jesus in that, who was obviously Jewish and was of that community?

Pell: Exactly.

Jones: So intellectually not up to it?

Pell: Well, that’s a nice try, Tony. The people, in terms of sophistication, the psalms are remarkable in terms of their buildings and that sort of thing. They don’t compare with the great powers. But Jesus came not as a philosopher to the elite. He came to the poor and the battlers and for some reason he choose a very difficult but actually they are now an intellectually elite because over the centuries they have been pushed out of every other form of work. They’re a – I mean Jesus, I think, is the greatest the son of God but, leaving that aside, the greatest man that ever live so I’ve got a great admiration for the Jews but we don’t need to exaggerate their contribution in their early days.

Jones: All right. You’re watching Q&A. Remember you can send your web or video question to our website. The address is on the screen to find out how to do that. Our next question is a video. It comes from Andrew Watson in Blackburn Victoria.

BIG BANG FROM NOTHING

Andrew Watson: Question for Richard Dawkins. The big bangers believe that once there was nothing, then suddenly, poof, the universe was created from a big bang. If I have nothing in the palm of my hand, close my fingers, speak the word bang, then open my fingers again, still I find there is nothing there. I ask you to explain to us in layman’s terms how it is that something as enormous at the universes came from nothing?

Jones: Richard Dawkins?

Dawkins: Well, obviously you’re not a physicist and nor am I and I am delighted to say that during my time in Australia I shall be having a number of conversations, public conversations, with my colleague Lawrence Krauss, including one in the Sydney Opera House later – I think it’s next week and he’s written a book on exactly that topic of how you can get something from nothing and I shall be questioning him about that. Of course it’s counter intuitive that you can get something from nothing. Of course commonsense doesn’t allow you to get something from nothing. That’s why it’s interesting. It’s got to be interesting in order to give rise to the universe at all. Something pretty mysterious had to give rise to the origin of the universe. Now, if you want to replace if you want to replace a physical explanation by an intelligent God, that’s an even worse explanation. It’s even a more difficult explanation. What scientists are trying to do is to explain how you can get not just something but the immense complexity of the world, of the universe and of life, and science is making a pretty good fist of doing that. Life is now completely solved barring the details. That was Darwin’s contribution and Darwin’s successors. Physicists are still working on the origin of the cosmos. Among them is Lawrence Krauss whom I shall be talking to next week. Now, it is very mysterious how the universe came into being. It’s a deeply mysterious and interesting question.

Jones: And can I just interrupt? It’s an old question, a very old question. Thomas Aquinis in the 13th Century was asking this same question. He said there must have been a time when no physical things existed but something can’t come from nothing. That was his view. It’s just been repeated by…

Dawkins: Well, something can come from nothing and that is what physicists are now telling us. I could give you – you asked me to give you a layman’s interpretation. It would be very, very layman’s interpretation. When you have matter and antimatter and you put them together, they cancel each other out and give rise to nothing. What Lawrence Krauss is now suggesting is that if you start with nothing the process can go into reverse and produce matter and antimatter. The theory is still being worked out. It is a very difficult theory, mathematical theory. I’m not qualified to answer the question but what I am sure about is that it most certainly is not solved by postulating an intelligence, a creative intelligence, who raises even bigger questions of his own existence. That certainly is not going to be the answer, whatever else is.

Jones: George Pell.

Pell: Thank you. The trouble well, there are many troubles with Richard’s teachings but a fundamental one is that he dumbs down God and he soups up nothing. He continually talks as though God is some sort of upmarket figure within space and time. Now, from 450, 500 BC where, with the Greek philosophers, God is outside space and time. God is necessary, self-sufficient, uncaused, unconditioned. That’s the hypothesis you’ve got to wrestle with. The second thing is that Krauss says nothing about the big bang coming out of nothing and admittedly he comes clean about six pages from the end of his book and I don’t know whether Richard has read it that far because he gave it a forward. What he says is what Richard is describing as nothing is a sort of mixture of particles and perhaps a vacuum with electromagnetic forces working on it. That’s what Krauss is talking about under the heading of nothing and there’s a very good review of this in the New York Times, not a pro religious paper at all, where Krauss is absolutely denied and demolished, although especially by his supporters claiming that he says things come out of nothing. He doesn’t say that.

Dawkins: It’s a matter…

Jones: You can quickly respond to that.

Dawkins: You can dispute exactly what is meant by nothing but whatever it is it’s very, very simple.

(Audience laugh)

Dawkins: Why is that funny?

Pell: Well, I think it’s a bit funny to be trying to define nothing.

Dawkins: I take…

Jones: Well, can I put that to you as a question? Is it equally feasible, since you can’t prove the existence of God that the nothing you’re talking about is, in fact, some creative force?

Dawkins: If you talk about a God who is a creative intelligence then that is something very complicated and very improbable and something that requires explaining in its own right. The nothing that Lawrence Krauss is talking about, whether or not it’s what a naive person would conceive as nothing or what a sophisticated physicist would consider to be nothing it is going to be something much simpler than a creative intelligence. We are struggling – we are all struggling, scientists are struggling – to explain how we get the fantastic order and complexity of the universe out of very simple and therefore easy to understand, easy to explain, beginnings. Lawrence Krauss calls the substrate of his explanation nothing. It’s possible to dispute whether nothing is quite the right word, but whatever it is it is very, very simple and therefore is a worthy premise for an explanation. Whereas, a God, a creative intelligence is not a worthy substrate for an explanation because it is already something very complicated and it is no good invoking Thomas Aquinis and saying that God is defined as outside time and space. That’s just a cop out. That’s just an evasion of the responsibility to explain. That’s just setting out what you want to prove before you have even started.

Jones: Okay, let’s move onto a question – let’s move onto a question on evolution for Cardinal Pell. It’s from Jo Blades.

EVOLUTION AND THE CHURCH

Jo Blades: As a young Catholic scientist, I’d like to ask the Cardinal to clarify the Roman Catholic Church’s position on evolution and comment on whether the dichotomy between science and religion is, in fact, real?

Pell: Well, science and religion are two different activities and in the Catholic Church you can believe, to some extent, what you like about evolution. I think Darwin made a great contribution. I remember talking with Julius Kornberg, a very distinguished biologist, and he’s worked with ants for years and he said, you know, he’s managed to change them by changing the conditions but there are a number of things that evolution doesn’t explain. Darwin realised that. Darwin was a theist because he said he couldn’t believe that the immense cosmos and all the beautiful things in the world came about either by chance or out of necessity. He said, “I have to be ranked as a theist.”

Dawkins: That just not true.

Pell: Excuse me it’s…

Dawkins: It’s just plain not true.

Pell: It’s on page92 of his auto biography. Go and have a look.

Jones: Sorry, can I just bring you, in a sense, to the point of the question? Do you accept that humans evolved from apes?

Pell: Yeah, probably. From Neanderthals, yes. Whether…

Dawkins: From Neanderthals?

Pell: Probably.

Dawkins: Why from Neanderthals?

Pell: Well, who else would you suggest?

Dawkins: Neanderthals were our cousins. We’re not descended from them and we’re both descended from…

Pell: These are extant cousins? Where will I find a Neanderthal today if they’re my cousins?

Dawkins: They’re not extant, they’re extinct.

Pell: Exactly. That’s my point.

Dawkins: Your point is that because they’re extant they can’t be our cousins.

Pell: I really am not much fussed.

Dawkins: That’s very clear.

Pell: Something in the evolutionary story seems to have come before humans. A lot of people say it’s the Neanderthal.

Jones: But can we say this: humans – you accept that humans evolved from non humans so let me put this to you as a question: at what point in this evolutionary scale was a soul imparted to the humans from God?

Pell: Look, a soul is not like putting a spot of gin in a tonic. The soul is the principle of life. So whenever there was a principle of life that could question, that could be open to awe, that was able to communicate then we had the first human. Now, we believe that the first humans developed in South Africa. I’m not quite sure how long ago and that all, you know, humans have developed from that. We know most about that. There aren’t remains. We know most about that because of the drawings they left on the on walls and caves and that sort of thing. No such thing from Neanderthals, so we can’t say exactly when there was a first human but we have to say if there are humans there must have been a first one. They might have been equal first but if there is a progression there’s got to be first.

Jones: So are you talking about a kind of Garden of Eden scenario with an actual Adam and Eve?

Pell: Well, Adam and Eve are terms – what do they mean: life and earth. It’s like every man. That’s a beautiful, sophisticated, mythological account. It’s not science but it’s there to tell us two or three things. First of all that God created the world and the universe. Secondly, that the key to the whole of universe, the really significant thing, are humans and, thirdly, it is a very sophisticated mythology to try to explain the evil and suffering in the world.

Jones: But it isn’t a literal truth. You shouldn’t see it in any way as being an historical or literal truth?

Pell: It’s certainly not a scientific truth and it’s a religious story told for religious purposes.

Jones: Just quickly, because the Old Testament in particular is full of these kind of stories, I mean is there a point where you distinguish between metaphor and reality? For example, Moses receiving the Ten Commandments inscribed directly by God on a mountain?

Pell: I’m not sure that the Old Testament says that God inscribed the Ten Commandments but leaving that aside it’s difficult to know how exactly that worked but Moses was a great man. There was a great encounter with the divine. Actually, with Moses we get the key that enables us to come together with the Greeks with reason because Moses said who will I tell the Egyptians and he tell that my name is “I am who I am”.

Jones: Okay, I’m just going to…

Pell: And we’ll come back to that.

Jones: I’m just going to bring Richard Dawkins back in here because we’ve moved from evolution obviously to the biblical versions of it. Your response.

Dawkins: Well, I’m curious to know if Adam and Eve never existed where did original sin come from? But I also would like to clarify the point about whether there was ever a first human. That’s a rather difficult and puzzling question because we know that the previous species from which we’re descended is probably homo erectus and before that some sort of australopithecine but there never was a last homo erectus who gave birth to the first homo sapiens. Every creature ever born belonged to the same species as its parents. The process of evolution is so gradual that you can never say, aha, now suddenly we have the first human. It was always a case of just a slightly different from the previous generation. That’s a scientific point which I think is quite interesting. I’m not sure if it has a theological significance except that I think successive popes have tried to suggest that the soul did indeed get added, rather like gin to tonic, at some particular point during evolution; at some point in evolution there was no soul and then later there was one so it is quite an interesting question to ask. Now we have rather a good fossil record from Africa of the descent of humans from australopithecines to various species of homo, perhaps homo habilis, perhaps homo erectus, then archaic homo sapiens and then modern homo sapiens. At what point did the soul get injected and what does the idea of original sin mean if Adam and Eve never existed?

Jones: I’ll just quickly let you respond to that, George?

Pell: Yeah, well, I mean God wasn’t running around giving injections and if there is no first person we’re not humans.

Jones: Where did the soul come from then in the point of evolution?

Pell: The soul is the principle of life. There are animal souls.

Dawkins: Do jellyfish…

Pell: All living things have some principle of life. An animal has a principle of life. A human has a soul, a principle of life, which is immensely more sophisticated. We even have a voice box, which is one of the great miracles, so we can communicate our thoughts to one another rather than just grunting.

Jones: I’m pleased we’re not grunting tonight. Let’s move along. You can – by the way don’t forget you can still vote at qanda.vote. Sorry qandavote.tv, I should say, on the question: does religious belief make the world a better place? Over 15,000 viewers have already voted and we’ll check before the end of the program for the final results. Our next question for Professor Dawkins and Cardinal Pell is a video and it comes from Kieran Dennis in Ferntree Gully, Victoria.

CLIMATE SCIENCE AND PROOF

Kieran Dennis: My question is for George Pell. George, as a climate cha00nge sceptic you demand a very high standard of evidence to support the hypothesis that global warming has an anthropogenic cause. My question is why then do you not demand the same standard of evidence for the existence of God?

Jones: George Pell?

Pell: I am very, very happy to answer that. First of all I’m not a sceptic about climate change. I grew up in Ballarat. The weather was always I worked for years in Melbourne. If you don’t like the weather in Melbourne, wait 20 minutes. Think of all the nonsense people like Flannery told us about years of drought here and now we’re coping with flood. But the droughts will be back.

Jones: So can I just clarify that you’re a sceptic about global warming leading to climate change?

Pell: I am sceptical – I’m sceptical about the human contribution to dangerous climate change. I think that is not established.

Jones: And, sorry, is that because you’re sceptical about scientific consensus and is that partly driven by what scientists believe about religion?

Pell: No, got nothing to do with it. On the weather question, I go on the evidence. When you come to talk about God, that is not a scientific question. The scientists concede that. It is a question that is open, I believe, to reason. You have to reason about the facts of science, ask whether you believe the suggestion that, you know, random selection is sufficient and also most evolutionary biologists today don’t believe that.

Dawkins: Don’t believe what?

Pell: They don’t believe in random so this crude fundamental gist version of random selection that you propose

Dawkins: I do not propose it and I strongly deny that evolution is random selection. Evolution is non-random selection. Non-random.

Pell: So there is a purpose to it is there?

Dawkins: No.

Pell: Could you explain what non-random means?

Dawkins: Yes, of course I could. It’s my life’s work.

Jones: It’s a hard thing to say but keep it brief.

Dawkins: There is random genetic variation and non-random survival and non-random reproduction which is why, as the generations go by, animals get better at doing what they do. That is quintessentially non-random. It doesn’t mean there is a purpose in the sense of a human purpose in the sense of a guiding principle which is thought up in advance. With hindsight you can say something like a bird’s wing looks as though it has a purpose, a human eye looks as though it has a purpose but it has come about through the process of non-random natural selection. There is no purpose in the human sense. There is a kind of pseudo purpose but it’s not a purpose in the human sense of conscious guiding. But above all I must stress that Darwinian evolution is a non-random process. One of the biggest misunderstandings, which I’m sorry to say the Cardinal has just perpetrated, is that evolution is a random process. It is the opposite of a random process.

Jones: A brief response to that if you can?

Pell: Yes. That is fascinating because most evolutionary biologists today believe that the animal world is developing accord to go patterns which we’re starting to know more and more about them.

Jones: Are you referring to intelligent design?

Pell: No, I’m not. I’m leaving that right to one side.

Jones: Do you believe in intelligent design? Or that there is an intelligent designer?

Pell: I believe God is intelligent.

Jones: No but it’s obviously a loaded question but do you believe in intelligent design and an intelligent designer?

Pell: It all depends what you mean. I believe God created the world. I am not entirely sure how it works out scientifically. But I wonder, you know, whether Richard believes that the order, the patterns we see in nature, whether they are real or whether they’re an illusion.

Jones: I’m going to leave that question for the…

Dawkins: They are real.

Jones: All right. Okay. That’s a quick answer. Let’s go to our next question. It is a video from Matthew Thompson in Toowong, Victoria (sic).

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN I DIE?

Matthew Thompson: I am an atheist. What do you think will happen when I die and how do you know?

Jones: George Pell, we’ll start with you? You ought to be an authority on this, I imagine?

Pell: Well, I know from the Christian point of view, God loves everybody but every genuine motion towards the truth is a motion towards God and when an atheist dies, like everybody else, they will be judged on the extent to which they have moved towards goodness and truth and beauty but in the Christian view, God loves everyone except those who turn his back turn their back on him through evil acts.

Jones: So atheism is not an evil act?

Pell: No, not – well, no, in most cases it’s not.

Jones: So I guess to get to the point of the question, I suppose – I mean he may be having a little wager here but is it possible for an atheist to go to heaven?

Pell: Well, it’s not my business.

Jones: You’re the only authority we have here.

Pell: I would say certainly.

Jones: Yeah.

Pell: Certainly.

Jones: Just on the subject of heaven, if we can, what is your own concept of what heaven is?

Pell: Well, even St Paul was severely agnostic but one way in which the Christians differ from the Greeks, the Greeks believed in the immortality of the soul. We Christians believe with one section of the Jewish people in the resurrection of the body.

Pell: So in some sense we will be there as continuing persons. In some with a new heaven and a new earth with all the good things that we’ve done will be incorporated into the new heaven and new earth. How it will work out I don’t know because, I think, physically and morally and intellectually we’re at our peak at different stages in our life. How it will work out I’ve got no idea but that is the general outline of Christian teaching.

Jones: But you think about it as a kind of collection of individual souls, in fact obviously billions and billions of individual souls with their own personality existing in some galactic space?

Pell: I think that’s a traditional well, that’s certainly the traditional Christian view. It’s the view that I accept and it’s also the view of some of the Jews.

Jones: Richard Dawkins?

Dawkins: Well, the answer to the question of what’s going to happen when we die depends on whether we’re buried, cremated or give our bodies to science.

Jones: Can I say this: if you’re actually an agnostic and you keep aside a small portion of your brain for subsequent proof, I mean, you might get presented with that proof when you die.

Dawkins: The brain is what we do our thinking with. The brain is going to rot. That is all there is to it. I am intrigued by the Cardinal saying that Christians believe you’re going to be resurrected in the body. I mean that’s an astonishing idea and I don’t believe you really mean that and I think – just as I don’t believe you really mean that the wafer turns into the body of Christ. You must mean body in some rather special sense.

Pell: Mr Dawkins, I don’t say things I don’t mean.

Dawkins: Well, then what do you mean then?

Pell: I’ll tell you and I’ve just explained what the bodily resurrection means to the extent that I can understand it. I certainly believe that when the words of consecration are uttered that they become the body and blood of Christ. Now, I have had a little kid come up to me when that was explained and say, “Can I have a look in the challis and see if it has turned to blood?” Of course it hasn’t. We don’t believe that. It’s not against reason. I believe it because I believe the man who told us that was also the son of God. He says, “This is my body. This is my blood,” and I’d much prefer to listen to him and take his word than yours.

Dawkins: But other Christian denominations are quite happy to take that as a symbolic metaphorical meaning. Catholics take it as a literal meaning and I take it – I’m trying to be charitable by trying to suggest that it’s that same sense in which you say that the body is resurrected because the body is certainly not resurrected in terms of the cell, the protoplasm, the proteins, the DNA. That doesn’t happen any more than the wafer turns into that. You’re right when you said that to the child. So you do not mean that the wafer turns into the body in any sense in which normal English language usage would understand. You mean it in some other sense and I take it it’s that same sense that the body is resurrected.

Jones: Can I ask you whether you mean it in a metaphorical sense in the same way that you believe Adam and Eve are metaphorical creatures?

Pell: No, I don’t. I follow it, I understand it, according to a system of metaphysics. It was spelled out by the Greeks before Christ came, which we have adopted and that is there is a substance which is the core of a being and it is revealed to us through what are called accidents. Now, I believe that the core of the being becomes the bread, becomes the body and blood of Christ and continues to look exactly as it was. We believe that in the Catholic Church. Now, I know you’re a cultural Anglican and we can’t blame the Anglican…

Dawkins: I’m also a rationalist. I mean I use – English is my native language. The wafer does not become the body of anybody in the English language.

Jones: Okay. All right. No, I think you both disagree on this point rather substantially. Let’s go to the next question from Michael Matty.

CHILDREN AND “NO GOD”

Michael Matty: Is it okay to tell a child that God doesn’t exist?

Jones: Richard Dawkins?

Dawkins: I think it is okay to tell a child the truth but I would prefer to encourage a child to make up her own mind and to think about the evidence and to believe things when there is evidence. What I think is not okay, what I think is deeply immoral, is to tell a child that when she dies if she’s not good she’s going to go to hell. That seems to me to be mental child abuse and an utter disgrace.

Jones: Okay.

Pell: I remember when I was in England we were preparing some young English boys, they were from very…

(Audience laugh)

Pell: Preparing them for…

(Audience boo)

Jones: Come on.

Pell: Thank you. Preparing them for the first communion and they were very patriotic young lads and one of them announced very breezily to me that he didn’t believe in hell and I mean certainly the idea of any child being sent to hell, I agree that that is grotesque and that’s not the Christian God but, anyhow, I said to this kid – I said simply “Hitler. You think Hitler might be in hell? Started the Second World War, caused the death of 50 million or would you prefer a system where Hitler got away with it for free?” Anyhow the little kid was quite patriotic and he said, “Mm.” He realised hell was in with a chance if Hitler was going to go there.

Jones: What about a system where he was obliterated and didn’t exist anymore?

Pell: Well, he would have got away with too much, as far as I am concerned.

Jones: So you actually – well, prefer the idea of hell as a place of punishment for – but for who? Where do you draw the line? Do unbelievers go to hell?

Pell: No. No. No. The only people – well, one – I hope nobody is in hell. We Catholics generally believe that there is a hell. I hope nobody is there. I certainly believe in a place of purification. I think it will be like getting up in the morning and you throw the curtains back and the light is just too much. God’s light would be too much for us. But I believe on behalf of the innocent victims in history that the scales of justice should work out. And if they don’t, life is radically unjust, the law of the jungle prevails.

Jones: Okay, I’m just going to go to our next question which we can respond to some of the issues through that. It is a video question. It comes from Mick Walsh in Nyngan, New South Wales.

SUFFERING

Mick Walsh: How can there be a compassionate God who is all powerful and has created us, yet we suffer? Why create such a world in the first place?

Jones: Richard Dawkins, you can reflect on that and the previous question.

Dawkins: Well, it’s hardly my business to say how could a compassionate God like that exist. Darwin himself said it was impossible for him to believe in a God who was capable of creating such suffering. He actually was talking about suffering in the animal kingdom.

Jones: Do you assume that suffering is a natural part of the human condition?

Dawkins: It is a natural part of the living condition. It is a natural part of Darwinian natural selection, which is one of the reasons why I was so keen to say that I didn’t want to live by Darwinian principles. There is massive amount of suffering in the natural world, a huge amount of suffering and it seems to me that’s an almost inevitable consequence of Darwinian natural selection. I’m more interested, however, in what’s true than in what I would like to be true. It would be very nice if there were no suffering in the world. It would be very nice if there were a sort of natural scale of justice, as the Cardinal was saying, but I’m more interested in what’s true, so it’s not the business of an atheist to justify the ways of God to man. It is the business of a Cardinal.

Jones: Okay, let’s go to the Cardinal. The question was: how can there be a compassionate God who is all powerful and has created us and yet we suffer. Why create such a world in the first place?

Pell: I think that is probably the hardest question for us to answer.

Jones: Do you struggle with it?

Pell: Yes. If I get a chance to say to ask a question when I die I think I will ask the good God why is there so much suffering? That’s a problem for us. I think the greater problem and I will come back to the question because it is a very good one it’s at the heart of what we’re about. I think it’s a much greater problem for the atheist to explain why there is goodness and truth and beauty. Our problem is to cope with suffering. One of the unique I think, well, certainly special features of Christian teaching is the value of redemptive suffering and that is the significance of Christ suffering with us and dying on the cross. That helps people. My first Easter after I was a priest, it was in the hills in Italy. Very sad village. All the men were away in Germany or Switzerland getting big money, home only for three weeks a year and the people were coming in, coming to confession and coming for consolation. I was even wetter behind the ears than I am now. I didn’t know what to say and eventually I said to someone “Well, look, Christ suffered too. Christ had a bad run. Christ died on the cross and we believe that through his suffering good will eventually triumph”.

Jones: Can I take it to a bigger level that than the village, to the Holocaust, to genocide, to famine: if there is an omnipotent and all powerful God, why does he let these things happen?

Pell: That’s a very good question but if God is going to allow us to be good he’s got to give us freedom. There is no alternative to that and…

Jones: But he chose to intervene at different times in history to save the Jews when they were going over the River Jordan. I mean there are many times when, apparently, God has intervened in biblical times. Why not now?

Pell: Well, that’s I think revelation is complete. That’s a mighty question. He helped probably through secondary causes for the Jews to escape and continue. It is interesting through these secondary causes probably no people in history have been punished the way the Germans were. It is a terrible mystery.

Jones: There would be a very strong argument saying that the Jews of Europe suffered worse than the Germans.

Pell: Yes, that might be right. Certainly the suffering in both I mean the Jews there was no reason why they should suffer.

Jones: Okay. I’m just going to – we’re running out of time. I’m going to go to another question. It’s on a different subject. It’s from Anita Wu.

GAY EQUALITY

Anita Wu: Jesus preaches love thy neighbour as thy self so, Cardinal Pell, how can you be against giving our gay neighbours marriage rights when equality and respect are the fundamental foundations of loving and spreading love.

Pell: Well, it’s quite misleading and quite unfair to suggest that Christians hate homosexuals. Christians love everybody. We believe that marriage is between a man and a woman, that it is for the continuity of the human race. We believe that men and women are made for one another, spiritually, psychologically, physically. We believe that a man and a woman, a father with their children, is far and away the best and most efficient and most economical system to bring up children and governments should support it. For homosexual couples who have a union, well and good. There’s no reason why that can’t be…

Jones: Can I just interpose a quick question on this. We are running out of time. I mean do you believe that homosexuality, since it’s not a question of choice, is part of God’s natural order?

Pell: Creation is messy. I think it’s the oriental carpet makers always leave a little flaw in their carpet because only God is perfect.

Jones: But, sorry, are you suggesting that homosexuals are flawed human beings?

Pell: Not necessarily but what I am saying is I don’t think homosexual activity is simply the result of genetic makeup, because we are free. We can control our instincts and like with heredity and environment, a lot of this practice is learned. But whatever about it, we’ve got to try to support these people, show compassion, the Catholic Church has a great record there. We look after more HIV sufferers than any other non-government organisation but we don’t believe it is possible to have homosexual marriage.

Jones: I’m going to – we’re almost out of time. We’ve got time for one more question that both of our guests can answer. It’s from Katherine Shen.

GOD IS GOOD FOR US

Katherine Shen: As an atheist, Professor Dawkins, do you believe that believing in God for emotional support should be allowed even temporarily? Research has proven that people who believe in God has a better chance of surviving terminal illnesses, such as cancer, as well as living longer when they go to church. Do you think that believing in God is beneficial for our wellbeing even if God is an illusion?

Dawkins: It is perfectly possible that, as you say, believing in God has beneficial effects upon health. It’s possible that you’re less likely to suffer an ulcer for something of that sort but I do have to stress, I mean, that’s an utterly trivial argument compared to the truth of whether God actually exists or not. I mean that’s a really big question. It’s an important question, one that the Cardinal and I would agree on. If there is some minor benefit to health one way or the other – the evidence is not good by the way but even bending over backwards to suggest that the evidence is there, that psychosomatic illness may be healed, may be or alleviated somewhat by belief in God – psychosomatic medicine is well know. Placebos work. If God is simply a placebo that’s fine but I’m interested in whether he’s actually there.

Jones: Okay, Cardinal Pell, final work actually.

Pell: So am I. It’s a question of truth. Christians don’t present God as, like Santa Claus, something that a myth that’s useful for children and believing in God and being a Christian cuts both ways. More people were killed for their Christian belief in the last century than any other century, probably than all the other centuries combined. They died on principle to be faithful to Jesus so we might get some benefits. You know we mightn’t get ulcers, we might live a bit longer, that might have much more to do with our heredity but we follow Christ because we believe it’s the truth. I think it does bring a peace of mind. It does help us but sometimes it gets us into my life would be much simpler and much easier if I didn’t have to go to bat for a number of Christian principles.

Jones: Have you ever regretted that you do?

Pell: Sometimes I wonder.

Jones: Seriously?

Pell: No. No. No.

Jones: Okay. That’s all we have time for tonight. Before we go, let’s check the final results of tonight’s qandavote, with more than 20,000 of you voting. We have a 76% saying, no, religious belief does not make the world – religious belief does not make the world a better place. Please thank our special guests Professor Richard Dawkins and Cardinal George Pell. And next week on Q&A we return to worldly matters with Attorney General Nicola Roxon, the Manager of Opposition Business Christopher Pyne, international human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson; humanist philosopher AC Grayling and Middle East analyst Lydia Khalil. Until then, good night.

Broadcast date: Monday 9 April 2012

2 thoughts on “Debate Richard Dawkins vs Cardinal George Pell – Full Transcript”

None of the answers appear satisfactory to me and maybe to others also. 70% goes against God. If we cannot answer existence of God properly then why not say there is no God. It is easy to prove that God does not exist. We know that we are guided by destiny, Bible says that. We also know that we do not have freewill – Bible’s “sow-reap” statement proves that.

There are many examples to show that life can be precisely predicted by any high level yogi with the power of third eye, long before the events happen. That means universe is completely deterministic and precisely predictable. That means God cannot change anything in our life, and therefore not necessary, and is non-existent. For more on these concepts take a look at the free book at https://theoryofsouls.wordpress.com/

“The notion of God was purified as it went through the Old Testament.” What, the original notion of God in the holy bible was wrong? Or worse, God evolved into becoming a better god?