by Caran Wakefield

Pablo Ferraro’s original commercial for Doctor Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb teases the audience, offering a sample of the gutsy black humor and subversive political satire that made the film famous. The trailer commences with an atomic explosion, and quickly bombards the viewer with written questions, frenzied xylophone scales, and film shots, all spliced together at rapid-fire speed. The egregiously long title is voiced by three separate actors, starting with a monstrously intimidating, archetypical Igor character. “Doktor Strangelove,” he cackles, before perky piano music abruptly overtakes his sinister tone. An obliviously cheerful man continues: “Or, how I learned to stop worrying—” “—And love the bomb,” purrs a seductive female voice. The commercial moves so rapidly between such distinct ideas—the laughter of a madman, the blind testimony of the indoctrinated, and the allure of a sex kitten—that the separate sentiments blur together, leaving our addled emotional compass worse off than a computer modem in a magnet emporium.

Like the commercial, the film invokes such an extensive array of emotions that audiences are often uncertain whether to laugh or cry. The movie is classified as a black comedy, and the genre itself is at the very least an oxymoron, perhaps even contradictory to what we’d expect. Dark humor is a delicate balancing act expertly courting elements of comedy and woe; the final product rivals a rare chemical reaction produced by the most meticulous of laboratory procedures. Clearly, comedy and woe can coexist, but Doctor Strangelove demonstrates that these two features, born of the same situation and built with the same techniques, represent a way for ordinary people to exercise some degree of control over an extraordinary circumstance.

The standard introduction begins with a name, and unusual nomenclature abounds in Doctor Strangelove. Jack D. Ripper, the psychotic general who orders American forces to attack Russia, is permanently distinguished by the negative sentiment carried by his name. The distasteful name alludes to the infamous 19th century serial killer Jack the Ripper, known for killing and mutilating his female victims. The B-52 plane that drops the fatal weapon is dubbed “The Leper Colony,” a code name that designates the crew as incompetent, even degenerate. The commander, Major “King” Kong, shares his name with the hairy, misunderstood ape from the 1933 movie. Back in the Pentagon, the cautiously diplomatic President Merkin Muffley (derived from the word “muff,” a slang term for female genitalia) verbally battles his foil, the appropriately named Gen. Buck Turgidson (a Freudian allusion to a virile, “turgid” erection). The belligerent Gen. Turgidson attempts to use Ripper’s breach of authority to justify the escalation of the Western Capitalist/Eastern Communist war of ideology into an actual “shooting war.”

Through these unusual names, each character is baptized into the realm of the absurd. These are not the names of realistic characters as much as they are terms for cartoon caricatures. In spite of this hyperbole, the actors play their roles with true-to-life dedication and sincerity. We watch Ripper exploit a loophole in the military chain of command, and this crafty maneuver ultimately catalyzes a full-scale war with Russia. Perfectly conscious of the radical, subversive nature of his actions, Ripper knows that government officials will fight to override his plan, siege his base, and persecute him appropriately. Yet he stands tall, stoically clenching a cigar between anguished lips as the last remaining light in his office burns inquisitively across his weathered face. He maintains his decision to go to war, citing a fervent yet irrational need to protect Americans from a Communist plot to “sap and impurify our precious bodily fluids.”

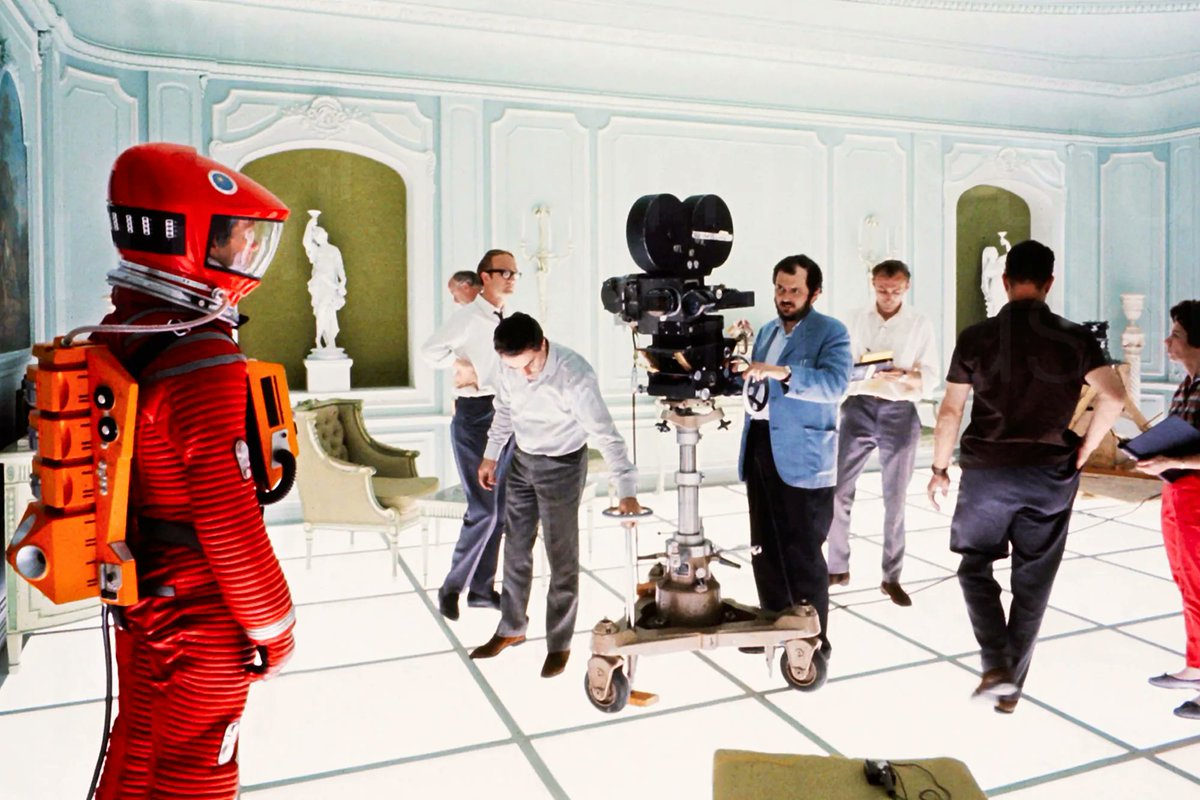

Major Kong, distinguished by a thick Southern drawl and low-brow colloquialisms, is a loyal commander and a dedicated citizen. Not only does he rally his men together and prepare them for a difficult battle, he also tries relentlessly to complete his orders to attack his designated target, even when it involves self-sacrifice. When the crew receives the fatal plan of attack, the traditional battle hymn “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” rings majestically in the background as homage to the misguided soldiers. This sonorous brass fanfare provides the only background music in the entire film, highlighting the heroic qualities of courage and loyalty that the crew demonstrates, even in the face of a faulty command. They have no idea that the orders they so diligently follow are issued by a madman. The music absolves these characters. Although the bomb that they detonate ultimately causes world destruction, director Stanley Kubrick presents them not as culprits, but as victims of an irony beyond their ability to comprehend.

Given the extreme circumstances and laughable names, the actors portray their roles realistically. Each character’s stubborn seriousness remains the comedic focal point. The actors could have easily built outlandish characters from the equally outlandish names, but the resulting humor would have been light-hearted and far removed from reality. Anyone can formulate a comedy through name-calling, exaggerated impressions, and ruthless slapstick, but this kind of charade emphasizes bawdy, tried-and-true techniques. In contrast, Doctor Strangelove draws its humor from the human condition. The movie’s seemingly outlandish plot does not stray far from history. Prof. Dan Lindley of the University of Notre Dame, who uses the film as a teaching tool, explains that “in its portrayals of Turgidson’s paranoia and the military’s strategies and tactics, Doctor Strangelove barely exaggerates. The American populace was paranoid and the U.S. military maintained a hair-trigger nuclear defense posture for a number of years” (665). When the film first came out, many audiences were unnerved by the lifelike sceneries depicted within the film. During the Cold War, Americans constantly feared the initiation of a deadly nuclear battle between the United States and Russia. This persistent dread eroded healthy thinking and gradually wore away at the American psyche, worsening feelings of anxiety, depression, and even paranoia. Because the plot does not stray far from reality, audiences could identify elements of themselves and their leaders within individual characters. Turgidson’s overzealous attitude towards war was not uncommon in many military commanders. These real leaders may well have sympathized with Kong’s crew, forced into frightening situations and subjected to harsh and unyielding demands while pertinent information was kept hidden.

During this period in history, thinking and behavior were influenced by government propaganda that reminded civilians to be wary of a nuclear attack and ever vigilant of government spies. Viewed in retrospect, Cold War Era propaganda easily lampoons itself, no comedians required. One poster, still available for purchase today, suggests that poor quality paper towels could create disgruntled employees. Bright red letters spell out a grave warning: “Is your bathroom breeding Bolsheviks?” Another government-issued film, cited in the documentary The Atomic Café, recommends that civilians keep firearms in their bomb shelters, thus dissuading any desperate neighbors who might try to force their way inside during a nuclear attack. An “Us vs. Them” mentality characterized American society, and flames of suspicion were fueled by the government. The same institution supposedly dedicated to the well-being of its constituents actually served to drive people apart at a time when they most needed interpersonal support. In a sense, free will and free thought gave way to these pressures and anxieties. Many people were reduced to nothing more than marionettes in a vile puppet show. Reluctant to admit that they themselves were the subject of a deranged comedy (for today we see the humor in what was once stark paranoia), they found refuge in an emotional fog and blindly went about their business, like the fatally unaware characters in Kubrick’s film.

These sentiments are described by author George W. Linden, as he recounts a spring 1964 screening of Doctor Strangelove. Although the audience recognized the Cold War satire as a brilliant “nightmare comedy,” they left the theater feeling “cold,” “heavy,” and “pessimistic.” As Linden explains, “The logic of the film was the logic of our lives . . . it was no wonder we had difficulty seeing the film as funny” (66). He admits that the film brilliantly brought out the humorous absurdity in the system of skewed reasoning inherent within his society, yet Linden still clings (perhaps subconsciously but certainly loyally) to this Cold War thought process. He still instinctively calls it “logic” (66). Kubrick acknowledges and rejects this faulty reasoning and rampant paranoia—the movie is an attempt to shock audiences into awareness by mirroring their ridiculous behavior through a larger-than-life depiction.

Peter George, author of the novel that gave rise to Kubrick’s film, also intended to shock his audience into action and awareness. Surprisingly, that may be the only similarity between the book and the film. Although Kubrick’s movie was renowned as a brilliant dark comedy, its satiric elements were a far cry from George’s work, originally titled Two Hours to Doom and published in America as Code Red. As a former RAF pilot, George had witnessed several situations similar to those depicted in the film and novel. Although none of these real-life conflicts escalated to an actual military strike, George, publishing under the pseudonym “Peter Bryant,” offered a stern, humorless warning about the dangers of the Cold War military-industrial complex. George tells a “pitiless, cruel story” because he considers the ideological battle at hand to be equally pitiless and cruel. “It is a story which could happen,” he cautions, “and then it really will be two hours to doom. Yours and mine and every living creature’s” (9). In this pseudo-fictitious scenario, the figurative Doomsday clock stops mere seconds before time runs out. The recall code is discovered, and all but one aircraft halt their attack. The remaining plane, badly damaged by an anti-aircraft missile, loses its radio capacity and continues the journey to its target, unable to give or receive messages. In a squalid, eye-for-an-eye bargain, the President permits Russians to destroy Atlantic City, believing that this concession will prevent an ongoing nuclear siege. At the last minute, Russian forces take down the rogue American plane, narrowly averting disaster. In Doctor Strangelove, Gen. Turgidson insists that the President utilize Ripper’s orders to wage war against those “commie rats,” reasoning that they could destroy 90% of Russia’s nuclear capabilities with “acceptable” American casualties of “ten to twenty million, tops.” This fail-safe strategy is never realized. Unlike the novel, Kong’s crew successfully destroys its Soviet target, triggering a chain reaction that ultimately ends in nuclear holocaust.

Lack of communication is the fatal flaw among Kubrick’s characters. Although Kong and his crew initially disbelieve their orders, Kong draws his own conclusions and motivates his men to take action. Far removed from their home base, transmission of information is sketchy at best, as we see by the gruesome end result of the Leper Colony’s mission. Each individual character seems personally isolated from the others, reflecting the super-imposed “Us vs. Them” mentality that was prevalent. When reconciliation and negotiation are more pertinent, all the President’s men become incompetent diplomats. The Russian Ambassador, Gen. Turgidson, and President Muffley are reduced to arguing, with no hope of reconciliation.

Although both the book and the movie contain similar elements, each work takes a distinct tone and a remarkably different ending. While Kubrick’s film is much more humorous than its literary counterpart, the result is more unnerving. Footage of mushroom clouds roll as music sweetly fills the background. Kubrick juxtaposes the apocalyptic scenery and singer Vera Lynn’s sweet serenade, creating a comic understatement. Lynn’s lyrics—“We’ll meet again some sunny day”—somehow hint at hope, while the images of destruction imply that we have nothing left to hope for. The ending scenes of the film emphasize the petty bickering among individuals. The scenes likely echo the 1959 “war of words” exchanged between Nixon and Russian Premier Khruschchev. Even when facing the prospect of the annihilation of the human race, Gen. Turgidson refuses to negotiate with the Russians, although humanity depends on the collaboration of the two superpowers. Kubrick’s characters demonstrate the same flighty unawareness as Lynn’s song. Their reluctance to consider opposing perspectives and their inability to grasp the significance of their behavior dooms them.

By incorporating echoes of real events, the film creates a subtle yet morbid foreshadowing of things to come. But how do we respond to leaders who play with the lives of civilians as casually as children play with marbles? What are the consequences of acting on juvenile grudges with grown-up ammunition? How do we respond to our country when it continues to push technology beyond moral and ethical boundaries? The universe becomes contradictory, and the absurdity of our reality is revealed. We are not characters in a farce, yet the film shows us that we are being treated as insignificant puppets in the grander scheme of government politics. Should we cry? Should we laugh? How do we react?

Composer John Adams and lyricist Peter Sellers (not related to the comedian) believed that these questions, brought to light during the Cold War, still resonate within our current society. In response to this concept, they created a contemporary opera exploring the doubts and anxieties that haunted various scientists as they tested the first atomic bomb. Their opus, titled Doctor Atomic, explores the moral and ethical quandaries faced by J. Robert Oppenheimer during his work on the Manhattan Project. While some only considered the bomb a decisive weapon in the war against the Japanese, Oppenheimer was haunted by the disturbing possibilities overlooked by fellow scientists. Oppenheimer recognized that the bomb would be a destructive and powerful force with the capability to annihilate humanity. Adams and Sellers communicate the trepidation and guilt that Oppenheimer experienced in the tense hours before the bomb’s first trial detonation via the emotional aria “Batter my Heart.” The piece begins with the pulsating, palpitating base drum that drives forward like a frantic heartbeat, while the other instruments fade in and out, inciting a melodic vertigo. This struggle abruptly yields to a dry silence, which represents both the barren desert scenery where the mysterious and terrible “gadget” awaits detonation, and the eternally lifeless scenery that the bomb could one day create. Unsupported by any orchestral flourish, Oppenheimer’s song of repentance borrows words from John Donne’s “XIV. Holy Sonnet.” In a voice weighted with sorrow, Oppenheimer pleads to God to “batter” (“better”) and “mend” his troubled heart. Yet the nightmare chorus breaks through again. Although Oppenheimer’s voice trembles as he begs divine forgiveness, the horrific reality of the situation cannot be so easily pardoned.

The opera considers the destructive power and human cost of atomic warfare, something deliberately overlooked in Doctor Strangelove. Everyone from fictional characters like Turgidson to historical figures like President Truman regarded atomic capabilities as powers bestowed by God to further American goals. While claiming a modern-day divine right from this nuclearpowered bully pulpit, perhaps officials did not feel compelled to explain the horrific effects or potential consequences of the bomb. Yet as Doctor Atomic makes clear, the weapon was created neither by God nor by “some warped genius,” but through the efforts of “normal men and women working for the safety of their country.” The bomb’s dark power is comparable to Prometheus’s fire, ripped untimely from the hands of the gods and placed into the hands of humans who lacked both the moral and ethical means to use it wisely. Even so, this grim subject matter informs Doctor Strangelove’s comic identity. David Worcester, author of The Art of Satire, explains that sensible characters “with proper respect for heaven” cannot exist within satire (113). Sensible characters divert their path before incurring any devastating consequences. Satire emerged as a way of chronicling the stories of those wretched souls who defied the will of the gods. And as legend has it, the ultimate penance is reserved for those who transgress almighty forces.

Doctor Strangelove, then, is the story of those who openly scorn these higher powers. Whether from the forces of nature, reason, or some distinct deity, the repercussions are the same. The universe spins out of balance. In myths and legends, the gods deliver swift justice to wrongdoers, but in a modern society where miracles are scarce, this responsibility falls to ordinary people. Given the unequal distribution of power, this imposing task appears all the more daunting.

When we feel otherwise helpless, humor offers us a way to reshape our mysterious and imposing universe to locate and ridicule the source of our faulty thinking. Kubrick’s keen political satire finds unexpected kinship in Shakespeare’s groundlings, who spend their days working in a cemetery, constantly surrounded by bones and bodies. Death is omnipresent in this macabre scenery, yet the gravediggers refuse to be controlled by fear or the uncertainty of their fate, the same elements that later ensnared their Cold War counterparts. Showcasing their shrewd wit through jokes and riddles, the groundlings bamboozle more illustrious men. One gravedigger queries: “Who builds stronger than a mason, a shipwright, or a carpenter?” And another responds: “The gallows maker, whose frame outlives a thousand tenants” (5.1.35-38). This “gallows humor,” conceived in tragedy, represents the transformation of something dark and confusing into a tangible, usable, humorous force. Its vessels—“clowns,” “gravediggers,” or “groundlings”— represent the collective. They are nameless, timeless, exercising sagacity sharp as a guillotine to “do well to those that do ill” (5.1.40). Claiming that all people have flaws is as obvious as claiming that all are mortal. In this modern world, judgment must ultimately be rendered by the groundlings, by us, or by other powers capable of seeing the absurdity in a transgressor’s behavior.

Although the dissenting group may initially lack the means to contend with their oppressor, piercing humor strips higher-ups of their eminence, redistributing power to the hands of the people. As Princeton professor Robert C. Elliott affirms, “Humor paves the way for action”—even the lofty Jesus Christ was first ridiculed before he was crucified, priming him to be stripped of power and dignity (85). Perhaps a ruling principle must be made ridiculous before it can be overthrown. The executers of this technique need not be illustrious; black satire simply brings preexisting flaws and contradictions into a harsher light. The subjects essentially condemn themselves, and so satire can only be effective in a world replete with flaws, never a utopian universe. Satire offers a means for underdogs to overturn the prevailing order, creating changes from the bottom up. Comedy becomes a key element in the system of checks and balances, perhaps even the essence of democracy.

WORKS CITED

The Atomic Café. Dir. Jayne Loader and Kevin Rafferty. Archives Project, 1982.

Doctor Atomic. By John Adams. Dir. Peter Sellers. Perf. George Finley. Amsterdam, 2007.

Donne, John. “XIV. Holy Sonnet.” The Complete Poetry and Selected Prose of John Donne. New York: Modern Library, 1994. 252.

Doctor Strangelove: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Dir. Stanley Kubrick. Perf. Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Sterling Hayden, and Slim Pickens. Columbia, 1964.

Elliott, Robert C. The Power of Satire. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1960.

George, Peter Bryant. Code Red. New York: Rosetta, 1958.

Linden, George W. “Dr. Strangelove and Erotic Displacement.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 11 (1977): 63-83.

Lindley, Dan. “What I Learned Since I Stopped Worrying and Studied the Movie: A Teaching Guide to Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.” PS: Political Science and Politics 34 (2001): 663-67.

Shakespeare, William. The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke. 1603. New York: B&N, 1966.

Worcester, David. The Art of Satire. New York: Russell, 1960.