Siegel Interviewed

This interview with Siegel is in fact fabricated by stitching together extracts from a number of different, already existing interviews. I have cut away most of the anecdotes and incidental details that usually characterise interviews in order to highlight and clarify Siegel’s attitudes to his work and his estimate of it. Too often interviews with directors treat the director as if he were the source of final illumination of the films he has directed. This interview should not be looked at in this way. Rather it should be seen as an account of one very important part of the production process, but an account that has to be evaluated and integrated with accounts of other parts of the process.

Working Methods

(Relations with producers) You’re given a script. Now the man who is giving you the script, if he is a good producer, has a good property and has worked well with the writer. Hopefully he’s not himself a frustrated writer. He should encourage the director to give the film the director’s signature, so that it will be put on the screen with the director’s talent. This needs the producer’s encouragement. Many producers are so jealous of their prerogatives that there’s an instant antagonism between producer and director. For that reason alone I like to produce and direct my own films. It eliminates one road block. There are many other road blocks but that at least is one that can go.

(Preparing the script) The stage of the film that I consider most important is the area of creating the script so that it can most effectively be put on film. I feel that a director and a writer must form a happy marriage and that what is going to be on film must be put on paper. I spend a great deal of time, in fact most of my time, in working on the script.

(Preparing the shooting) I have the advantage of being able to envisage cinematically what I intend to do. Now if I don’t know what the set looks like, forget it—there’s no point in any planning. If I don’t know what the location looks like, there’s no point. But if I do know, I can sit in front of the typewriter with the script in front of me and have total recall of the set and where the doors are. I might have—not a sketch because that would be much too expensive—but a plan lay-out or, if at all possible I would have seen the set the day before so that I would know where all the furniture was, the placing of it, and then I would lay it out as I think it would be cut. It’s stupid for a director to lay it out the way its going to be cut if he’s not an editor, and doesn’t understand editing—he’s just wasting his time. Let us presume for the moment that I’ve laid it out satisfactorily as an editor. Now, because of lack of time in shooting, I lay it out in terms of my shooting continuity, which does not mean that it will interfere with the type of shot that I’m going to make, but that I’ll complete shooting in one direction before I turn around and shoot the other way which saves an enormous amount of time in moves and in lighting . . . the actors aren’t confused because I always rehearse the scene as a whole so that everybody knows exactly what he is doing . . . Now remember I am not talking about the qualitative aspect of what I do. I am talking about time and expense, factors important in determining if the picture will make or lose money. A good picture that loses money is not what any director wants.

(Relationships with cameramen) I respect the cameraman and I can only tell him what I want out of a scene and give him courage that in case there’s nothing on the film, I’m going to back him up. Occasionally I’ll notice that the scene is being overlit . . . and I’ll point out that I think he should take another look at it, that there’s too much light. I never encroach on his domain or undermine him with his crew. I don’t rely on cameramen to give me the set ups, but the lighting I do think is their problem. A lot depends on which cameraman is working with me. Some cameramen I can’t communicate with at all.

(Relationships with actors) I don’t go into esoteric discussions about the part if it isn’t necessary. And particularly I don’t bugger about with the actor if he’s doing well. If, by some miracle, I’m working with an actor who’s got a marvellous concept—I leave him alone, and just guide him, or hold him down and explain that if he’s going to get this violent at this point, he’s going to have nowhere to go later on in the picture. That’s about it.

(Editing) After shooting a picture, I stay away from it for a while. I’ve been terribly close, don’t forget, throughout all the stages: writing of the screenplay, casting, finding locations, wardrobe, building of sets, endless work. I’ve had it. I need a rest. Then when I look at the first assembled picture, I don’t want anyone to talk to me. I just look at it as a whole. I want to look at it in its total fullness, so I have some feeling that: God, this picture’s slow, or Wow, it’s good, or Jesus I have to do something about such and such. The result is almost always the same. I’m livid with myself for many of the terrible things I okayed. I go home, thoroughly depressed. But an anger is building up and I come back the next day and I just can’t wait to get at the goddam film and rip it to shreds. For, at that point, nothing in the film is sacred, absolutely nothing. I couldn’t care less if I took half a day to get a shot. If I don’t think it works it goes. I couldn’t possibly leave decisions like this to an editor.

Artistic Techniques and Aims

I like my villains not to be stupid. Gosh, I want my villains to be brilliant and that makes my hero that much more brilliant. I loathe these anti-Nazi pictures where the Nazis are a bunch of dopes. I mean, what are you defeating? You have to be very careful if you have a hero who in reel 1 knocks out twelve guys. What are you going to think when he comes up against one guy at the end?

You always have the feeling in looking at my pictures, that there’s a great deal more violence than there really is. The violence is imminent, latent. At some stage the violence is tremendous, so that you know it’s going to explode rather than to have every sequence with people getting senselessly beaten up … I like the violence to be essential to the telling of the story. I don’t like violence for violence’s sake. I’m extremely uncomfortable with it. So many pictures today go out of their way to linger on it. It’s in very bad taste and it’s very poor drama. After a while you’re just bored with it; it has no meaning. … You know when I began I had no gift for violence. Then I did second unit filming. I became a specialist on brawls and fights, I was filed amongst the action directors. But really I’d love to make comedies, or love stories like Brief Encounter.

I do not make films with necessarily a message, I try frequently to make them for entertainment. I do not feel that this is a shallow point of view inasmuch as I do try to make my films as realistic and as interesting as possible … We are in a commercial business and pictures should be made so they are commercially successful. I’m not interested in making pictures people don’t go to see . . . Once I accept a picture, even if I know the script is terrible, I’m committed to it. I have no other thought than to do it as well as I can.

Hollywood

The lack of freedom in Hollywood is pretty obvious. It is reflected in the main by the stupidity of producers in general. It is difficult to envisage anything that Hollywood could do which would compensate for the lack of freedom excepting giving one more freedom . . . Today there’s more freedom of expression. Censorship plays a less and less important role. Good taste in the last analysis is what counts. The invasion of highly regarded foreign films and their important effect on receipts have definitely changed the ‘Hollywood’ mentality. There is a marked tendency to give the director full responsibility and enough rope to hang himself. This is all to the good. All I ask for is the marvellous opportunity to make my own mistakes.

… I rarely say anything good about a major production company whether I’m working there or not. If I should find out to-morrow that I’m not working at Universal, I know that financially I’ll be able to do much better, working independently, so that it isn’t that I’m trying to curry favour with Universal. But there’s a new spirit at Universal. The one thing I envy in French and English directors is their apparent freedom. The man I’m working for, Jennings Lang, who’s the executive in charge of all the productions I’m connected with now, believes in giving directors as much freedom as he can. Obviously this has to be tempered by how well the director’s going, and, I suppose, how he feels about what the director is doing. This can change tomorrow and I may tell you that I can’t work with Jennings. But today I have to say that it’s very exciting working for him because he not only gives you freedom but he feeds you with ideas. He seems very genuine in wanting to do the best work that can be done. What more can I ask? Sure I want to make a lot more money, but it’s very important to me that I’m happy in my work and right now I’m happy.

… I think the situation of working at a major studio is so hopeless that if you don’t make a game out of dealing with it, you’re going to go crazy. So I gear myself to enjoy, within the limits of not losing my sanity, the constant fighting, the constant trying to do something better than they want me to do. My first impulse is to say that I’d like to be free of my contract because I could make more money. However, I have an enormous suspicion that if I were suddenly free, all the offers from outside would stop and I’d want to be back at Universal.

Television

I’m asked if I prefer working in the cinema or television. If I have the chance to express myself as I want and to make a really good film (always being sure of two vital conditions: time and money) obviously I don’t have a preference. My ambition is to make a really good film and whether it is destined to be shown in the cinema or on television doesn’t interest me. I’ve made a number of films with limited budgets which were very hard to make and which have then been successes, both critically and from a box office point of view. For example Riot in Cell Block 11 which was made in 16 days, Invasion of the Body Snatchers which was made in 20 days, Baby Face Nelson which was made in 17 days for 175,000 dollars. I’ve been happy to make such films, perhaps because they have been well received. If my present project (The Killers) works out I don’t see why I shouldn’t be happy working for television.

In making a film for television there are certain working conditions that are a great help to a director. Everybody is prepared for shooting to take the least possible time. Everybody expects to work very hard, the highly paid stars and cameramen as well as the grips and electricians. In the cinema I’ve worked with cameramen who take their time and cause the film to get behind schedule. I’ve worked with the same cameramen in television. They know, when they accept a television contract, that they’ll be allowed a certain number of days (and hours per day) and a clearly defined budget. If they can’t work in the time allowed, somebody else will.

In most cases the speed with which the director works is dependent on the cameraman. In television, if the cameraman isn’t quick—and I don’t mean that his work should be mediocre and slapdash—it’s simple: he doesn’t get another contract. The same is true for the director. If he’s slow he isn’t reengaged. However, the fact that the director doesn’t have time to work out beautiful compositions and has to figure out all his shots in advance, can be an advantage. He is forced to shoot simply which is often the best way of shooting. And having worked out a ‘pre-montage’ he is in a good position to supervise the final editing.

At present people are unanimous in their scorn of television methods. Many of the criticisms are justified but often they are defence mechanisms for the director. Trying to protect himself he complains that he didn’t have enough time, that the shooting stage wasn’t properly equipped, that the casting wasn’t right or that the script was stupid. But maybe he failed to improve the script, didn’t talk with actors he knows and persuade them to work for less money and there’s always the chance of rethinking the shooting so that it can be done with the facilities that are available.

… I must say that most of my peers are phony when it comes to directing for television. They are in television for the same reason I was, to make money. I can’t see any other reason to do it. You have less time to work, less time to prepare and absolutely no post-production time. So I don’t understand when they start talking artsy-crafty about what they do on television. Most of the work done on television is poor, as far as directing is concerned. If you’re going to be in television you should be a producer, because a director is not important. On a series you have a regular producer, cameraman, crew and cast. When a director steps in he doesn’t wield much authority.

When I have done television shows, I kept the right to do the first cut, the first job of editing. Most directors can’t afford that. They do a 3-day show and they’ve got another one the next week. Most directors on television don’t even have time to look at the footage they’ve shot each day. Television directors direct traffic. When they do a good job, they deserve a lot of credit, but good television direction is rare, because television directing is so incredibly difficult. The preparation time is ludicrous and a director often finds himself reading the script on the way to the set.

Now that is not true about television pilots. You have time and you have money. The important thing is that you have to get some one to buy it. And when they buy it, they don’t buy what they are going to get on the series. The pilot for a one-hour show will have a big budget, a good director and several weeks of shooting. When the series starts, the director on a show will get no preparation time and a week to shoot. . .

Apprenticeship

I became an assistant editor. I found the job particularly dull and I was a very poor assistant. So when I had an opportunity to go on to the Insert Department I grabbed it; also it seemed great to have control of a camera unit, no matter how small. Any shot the director was too lazy to shoot automatically became an insert because I would go to the directors and I would say: ‘Why shoot Bette Davis getting out of a wagon and lumbering over to the house ? I’ll do that for you’. And of course that saved the director a bit of time.

Then from the Insert Department I moved over to Montages. Montages were done then as they’re done now—very sloppily. The director casually shoots a few shots that he presumes will be used in the montage and the cutter grabs a few stock shots and walks down with them to the man who’s operating the optical turner and he tells him to make some sort of mish-mash out of it. He does, and that’s what’s labelled Montage. I took an entirely different viewpoint along the lines of Slavko Vorkapich who was at Metro. It became without doubt the most exciting part of my film career including to-day and the most fruitful because literally out of nothing, and with no-one at the studio even being aware of what I was doing, I would write montages. I would do revolutionary things like having dialogue in montages. I only got away with this because I would say to them: ‘Well, who said there can’t be dialogue in montages?’. I was absolutely on my own. Nobody really knew what I was doing because the indication in the script would be that there was a lapse of time of 10 years or there would be a man looking for work and not getting it.

During my tenure at Warner Brothers as Head of the Montage Department, the studio became trained to look upon those situations in the script that called for montage, whether it was spelt out or not, as being my problem. I would take the script and write the montages. They wouldn’t dare mess with my scripts because they were always very complicated. Where it ran 1 line in the script, my montage might run 5 pages. Of course it was a most marvellous way to learn about films, because I made endless, endless mistakes just experimenting with no supervision. And the result was that a great many of the montages were enormously effective.

So I did travelling mattes, like in Confessions of a Nazi Spy and anything I could dream up. I would just do it. I wouldn’t know what I was doing but the effect would be fantastic. I think the good influence it has on my work today is that I don’t strain with the camera now. In fact I try very hard not to do exercises in camera technique except when they are directly helping me tell the story.

During about 7 years I shot montages, insert and second unit, I had more film in Warner Brothers pictures than any other director at Warner Brothers. In order to write the montages, I read every script that came out in all versions —in itself very time consuming because Warner Brothers might not have made many good films but they made a lot of pictures. I made a very severe effort to do montages in such a way that they did not attract attention to themselves but were in the spirit of the picture. In that way the directors accepted me.

Films

Star in the Night

I deliberately left montage out of the picture because I wanted to show that I could do other things beside montage. It was my first show and it was somewhat difficult in that for most of the shooting I had a great many people in one small room. But I thought it worked. I was never keen about the three cowboys, the Magi. I thought that section was a little coy and precious.

Hitler Lives

We were very strongly imbued with our hatred for the Nazis and we wanted to tell the world that Hitler’s spirit still lives, as it does even today. I think if we had the same short to do today, it would be done more with the left hand, with a little more humour, more sarcasm. It was purely an editing job. The man who deserves the most credit for it is the writer, Saul Elkins.

The Verdict

It was made during the strike. I was the only director working during the strike. I used to have to fight my way to get into the studio. I never knew what set I was using. I never knew who my cameraman was going to be, what actors were going to show up. It was largely improvisation but somehow I staggered through it and I thought for a first effort it was all right.

Night unto Night

It is one of my least favourite films. I fell in love with the leading lady which affected my direction and I did very little work on the script, which was a mistake. I didn’t battle with the producer, Owen Crump, who charmed me into accepting the script as it was. And the picture was miscast.

The Big Steal

At the time we made the picture, Mitchum was in jail on a marijuana charge. This script was a desperate attempt to prove to the court that RKO was suffering because Mitchum was in jail. He was actually assigned to this picture after he went to jail. When he was still in jail, I went down to Mexico and shot the end of each of the sequences of the chase first, Bill Bendix chasing Mitchum. Then three months later I went back to the same locations and shot the front part of the chase with Mitchum. Naturally my attitude towards the picture had to be one of fun because I didn’t take the story and whole situation seriously. You mustn’t judge this film on a very high level. Its standards are modest.

No Time for Flowers

To sum up that picture it was producing at its strangest. I was making a picture in Vienna but it was supposed to be in Prague. So every time I went on the street to shoot, the producer, Mort Briskin, said I couldn’t use the best sites, buildings and streets because people would recognise them and know it was Vienna. I might as well have shot it on the back lot. I thought the picture was a poor man’s Ninotchka.

Duel at Silver Creek

I remember going to see Goldstein who was the producer to ask permission to finish the script so that at least I would know who gets the girl. I didn’t think that was too awful a request for a director to make. He said: ‘Kid, how many pictures have I made this year?’ It was then November—I said: ‘Gosh, I don’t know I believe you’ve made an awful lot.’ He said: ‘I’ve made 19 and I didn’t make them by pushing them back two weeks.’ So I went into the picture not knowing whether Steve McNally or Audie Murphy got the girl. I couldn’t take the picture seriously.

The script was short. To make it look longer we left a lot of space between each shot description in the final big gun battle. It gave us a good page count, and the studio told us to go ahead and start shooting. I started to get compliments on the dailies from the executives and told them I was afraid we might be running short, but they said: ‘Keep up the same pace, don’t change anything.’ I wound up with a 54-minute movie and had to dream up a prologue about Audie Murphy and his father to expand it to 77 minutes.

Count the Hours

I never thought much of the picture. There are no miracles in a 9-day picture. With that picture we shot as fast as we could load the camera and get to the various locations.

China Venture

I went at it full tilt, I enjoyed shooting it. But again it’s the old thing that seems to plague me, and it’s got to be my fault in the final analysis. The story was weak; I didn’t know how to end it. I just didn’t know how to.

Riot in Cell Block II

I think it’s the best film made about prisons. It’s due to a remarkably intelligent producer, Walter Wanger, whose knowledge on the subject was unbeatable as he’d just come out of prison himself. He wanted his contribution to the subject matter to be absolutely honest and uncompromising. No star was allowed to unbalance our casting: only people like Leo Gordon, Neville Brand or Emile Mayer. We didn’t bring any women into the prison. The studio couldn’t get over the complete absence of a corrupt district attorney or a chief warden’s wife, or other cliches of this kind. We didn’t take sides at all.

Private Hell 36

I was terribly self conscious on the picture. I had just done Riot in Cell Block 11, in which I had great authority, did whatever I wanted to do. Now I was on a picture battling for every decision, working with people I didn’t feel free with. I was not able to communicate with these people and the picture showed it.

The Annapolis Story

Every piece of colour film ever made, of all sizes and shapes, was thrown together, anything we could find, 16mm or Technicolor photographs, anything you could think of. It was probably the worst mish-mash of colours ever done. We used the old Technicolor camera, you know, in the great big box. Again it was a cheating kind of picture—we didn’t go to Annapolis to shoot it. It was a back lot picture. I knew no other way to do the picture than to have some fun with it, and keep it alive and alert. It certainly is not a good picture.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

We spent very little on special effects, less than 15,000 dollars, with which our production designer, Ted Haworth, worked miracles. We concentrated on the story and the acting, instead of spending thousands on special effects and sticking wooden actors on the screen.

This is probably my best film because I hide behind a facade of bad scripts, telling stories of no import and I felt that this was a very important story. I think that the world is populated by pods and I wanted to show them. I think so many people have no feeling about cultural things, no feeling of pain, of sorrow. I wanted to get it over and I didn’t know of a better way to get it over than in this particular film. I thought I shot it very imaginatively. And I was encouraged all the time by Wanger. The film was nearly ruined by those in charge at Allied Artists who added a preface and ending that I don’t like.

The political reference to Senator McCarthy and totalitarianism was inescapable but I tried not to emphasise it because I feel that motion pictures are primarily to entertain and I did not want to preach.

Crime in the Streets

The whole picture was shot indoors. I thought it was a remarkable job and a good film. What was really wrong with the film was that it had a chilling identification for the average citizen, who loathed the film. I think because there was no excuse for what these kids did. You know people identified themselves with the man who was beaten up.

A Spanish Affair

I suspect that the whole thing was nothing but an elaborate tax write off for which I was well paid. It had a few saving graces. Sam Leavitt the photographer did really a magnificent job. If the picture had been better it would have won the Academy award, I think, for photography. It was a beautiful travelogue.

Baby Face Nelson

I found no excuses for Baby Face. He was a very despicable gentleman, completely neurotic who didn’t need to be explained or justified. Most script writers always try to psychoanalyse criminals. But Daniel Mainwaring and I were content to search through the papers of the time.

Mickey Rooney, who’s one of the most difficult people I’ve ever worked with, was absolutely superb in the role. It was marvellously photographed by Hal Mohr. I thought it had a great deal of vigour. It was made under enormous handicaps. It was made under an aura of unpleasantness, throughout, which maybe was reflected in the viciousness, because I took out my anger against everybody in the picture. It was very cheap. It cost 175,000 dollars to make and it took a lot of book-keeping to make it up to 175,000.

The Gun Runners

I thought it was absolutely stupid to remake To Have and Have Not and particularly to do it as a sea picture with a C budget. It was one of the most difficult pictures that I’ve ever done. That sea stuff was very difficult to do, and it was one of the most unsatisfactory pictures because I thought I had a poor cast. I might have gotten by if I’d had a better cast. It’s absolute insanity to remake these pictures on a smaller budget, with people of lesser stature. I was very much against making it, but I needed the money and I did the best I could. I worked very, very hard on it, and I’m sure the picture isn’t any good.

The Line Up

A great deal of the Eli Wallach/Robert Keith relationship was my contribution. Sterling Silliphant at that time was not the great, big, powerful Sterling Silliphant that he is now, and he looked upon me as a kind of old, excellent director, so he listened to me. We got along very well and I thought it came off well. I didn’t like the opening of the film. I always felt the picture should have started in the airplane with Wallach and Robert Keith’s conversation. I wasn’t interested in the detectives. I wanted to concentrate on the baddies.

Edge of Eternity

It was a picture that the studio made just to eat up commitments with Cornel Wilde. The canvas interested me, shooting it against the Grand Canyon. The picture again had a nothing story but the most horrifying and horrendous sequence over the Grand Canyon in the trolley that I’ve ever witnessed in my life. Remember that the story is not good and it’s made cheaply and I question the cast but at the end the sequence in the bucket, the sequence of the Grand Canyon, I guarantee your hands will be absolutely wet.

Edge of Eternity was my first wide screen picture. I don’t like the proportion at all. If you go to the museums and look at great paintings you’ll find that they are not in the shape of a band-aid. These wide screen processes are a gimmick. I prefer the older rectangular film shape. VistaVision, however, was a superb process.

Hound Dog Man

It’s possible for a film to be an assignment and to be involved in the script. Hound Dog Man was both. It was based on an excellent book, which we were not faithful to, because we were doing a kind of pseudo-musical. I tried very hard to go back to the book. I did the usual thing that I do when I’m on a picture, I immediately read the source material. Almost always I fall in love with the source material. My struggle was a struggle with their concept. They thought they had a gold mine in Fabian and they wanted it to be a Fabian vehicle—that’s where we were poles apart, much as I like Fabian. It was nice to do a picture that children could go and see. I wish I could do more.

Flaming Star

I was very conscious about not confusing the issue of non-acceptance of a half-Indian with the the question of racial prejudice against blacks. The question of prejudice against Indians was then, and is today, bad enough without using it as a simple metaphor. If our conclusion is pessimistic, it is because I can conceive of no other kind of conclusion for a film on prejudice if it is to be anything but a false conclusion.

Presley is a fine actor, but he’s given very little chance of being a fine actor. He’s totally under the domination of the Colonel, and it’s very difficult to prove that the Colonel’s wrong because Elvis Presley makes all the money there is in the world. So, they don’t want to change his image. I enjoyed doing it with Elvis, because Elvis comes from a section where there’s a great deal of prejudice—he’s on the other side in fact.

Hell is for Heroes

Hell is for Heroes is a film I inherited and which I didn’t begin. It’s an honest film which has something to say. At the beginning I refused to shoot certain scenes which seemed to me too anodyne, too delicate for a war film. It would have turned out more like a brass band regiment. But I do think war’s a sordid thing. I tried to get to the heart of it and my film is, I think, extremely realistic.

I really felt the picture began when we got up on the ridge. I thought that the stuff” in the studio was pretty obviously studio stuff, which was unfortunate. I think we’d have been much better and much less Hollywood if I’d just started the picture on the ridge, really right with it. But I wasn’t equal to it, and there was great pressure of time and quite a rewrite.

I’m particularly pleased with the last shot and, in fact, with the entire ending in which Steve McQueen is killed and the battle goes on as the picture ends. That wasn’t the end of the picture as we had written it. The end was more affirmative and we had shot it that way but when I was editing the picture I realised that at the peak of the battle I had nothing else I wanted to say, no feeling of possible affirmation. I wanted to show that my hero was blown up, which was horrifying, and that the rest were still going forward, that he would be forgotten, that the action of the war is futile. I hadn’t designed anything for an ending like that, so I optically zoomed in on the pill box. It didn’t bother me a bit that it was grainy. It had an authentic quality and it made me feel right about the picture.

The Killers

I wanted this brutal and sensual film to have a substantial reality and a point of view. I wanted one to feel the intelligence, the coldness and the cynicism of the killers, that their evil could be fascinating for the heroine, but for her alone, until the moment when she is a victim of it. I didn’t want my two killers, when they went to see a group of people, to spend their time beating them up, kicking them in the crutch or crushing their faces with their heels. I preferred to show right from the pre-credit sequence that they were capable of

everything: from the first shots, one sees them brutally beating a blind woman, then savagely battering down the hero point blank. The thing is so shocking that from then on I didn’t need to make them do anything more. They are preceded all the time by their gestures, they are dreaded. Their brutality is latent and the film, in fact, contains few enough violent acts.

Angie Dickinson plays her role admirably, but the motivations of her character remain obscure. I accept the entire responsibility because I reworked the script a lot. I was conscious of this vague area in my work, but I wasn’t able, if you like, to get away with it. Having concentrated on the killers, I unjustly emphasised the male protagonists.

The Killers was made for television but not initially released to television. It was completed shortly after President Kennedy’s assassination, and the studio thought it was too violent. I’m quite sure that in some way I was influenced by television, by the recognition that I had to be tight in on most things, that the long shots would have very little value, But I shot it as a feature. I shot it in the style which I feel is my style at its best, very taut and lean, with great economy. If I had to do it over, I don’t think I would change much.

The Hanged Man

The Hanged Man was a very strange assignment because the original was such a good picture, Ride the Pink Horse with Robert Montgomery. It was absurd for us to remake it, because we were not only remaking it on less schedule and less money in the budget, but we were making it much more complicated. It was extremely difficult to do a Mardi Gras on the back lot.

I shot it with a weak script that I didn’t like, feeling all the time I was making a real flop. And then during the editing something extraordinary happened. While cutting the film viciously, in a spirit of revenge, I engendered a real excitement.

I thought the ending was very artificial. It just fell apart. But it was done with great splash, vigour and colour and the studio was very happy with it. I hope I don’t do any more like that.

Stranger on the Run

I think for a one-twenty (a two-hour television film) it’s very good. I liked having Fonda. I like very much the fact that a man of his age is thrown off a freight car at the start of the picture. He’s a bum and doesn’t lick anybody. There isn’t anybody in the town he can lick. And then you go through a change at the end of the picture. Not that he could whip anybody, but he’s a man. He faces up to responsibility. I thought the picture was surprisingly un-Hollywood—and I’m not using that term to be contemptuous as it sounds. The ending of the picture had to show Fonda beating up Michael Parks: that’s the way the script was written. I changed it so they don’t have a fight; it becomes a duel of big close ups; they look at each other. Very different from the kind of ending one would expect to see. I like the fact that I got away with it. The music was terrible, except at the end.

Madigan

Fortunately for the picture and fortunately for me, there isn’t an awful lot you can do with the film I shot. Not getting along with the producer I shot it the way I thought the picture should go together, and didn’t shoot much coverage. It is more or less in the version that I shot except that little beginnings and endings are cut off. It’s a little sharper than I shot it. Then a lot of lines were in that I had nothing to do with . . . Anyway I don’t want to talk about that end of it because I’m prejudiced. But I’m lucky and grateful that the picture apparently did turn out well. I was very worried about it.

It’s a realistic approach to what undoubtedly does take place. A man in the kind of jam Widmark’s in isn’t going to stand on formalities. He’s going to have one idea in mind and that’s to find the guy who took his gun away. A lot of questions are raised about Widmark by the Commissioner, Fonda, who certainly doesn’t approve of the way this man operates. But this is a real person. I’m not making a picture and saying whether Widmark is right or wrong, but I’m just saying this is the way he is.

There are a lot of cops like that, a lot of cops who’d belt you right in the mouth if they thought they were going to get an answer from you. They wouldn’t think two seconds. They become brutalised by the brutal work they have to do. It doesn’t mean anything, it’s like a doctor looking at blood. I’ve been very close to a lot of police and a lot of them are my good friends. They have no idea how brutal they are. They laugh and they talk about how they pull this big negro in and he’s bleeding all over the place. Then all of a sudden they look up and there’s the probation officer and they think —Oh God here we go again. And they’ve no idea they’ve done something cruel. They’re talking to me and I’m their friend. I’m horrified.

Death of a Gunfighter

Totten did the first half and I did the last half but I had nothing to do with the sets, decor, make-up or casting. In addition I had not worked with the writer in preparing the script. So when I was asked to let my name be on the credits, I refused. A director’s job is more than yelling ‘Action’ and ‘Cut’.

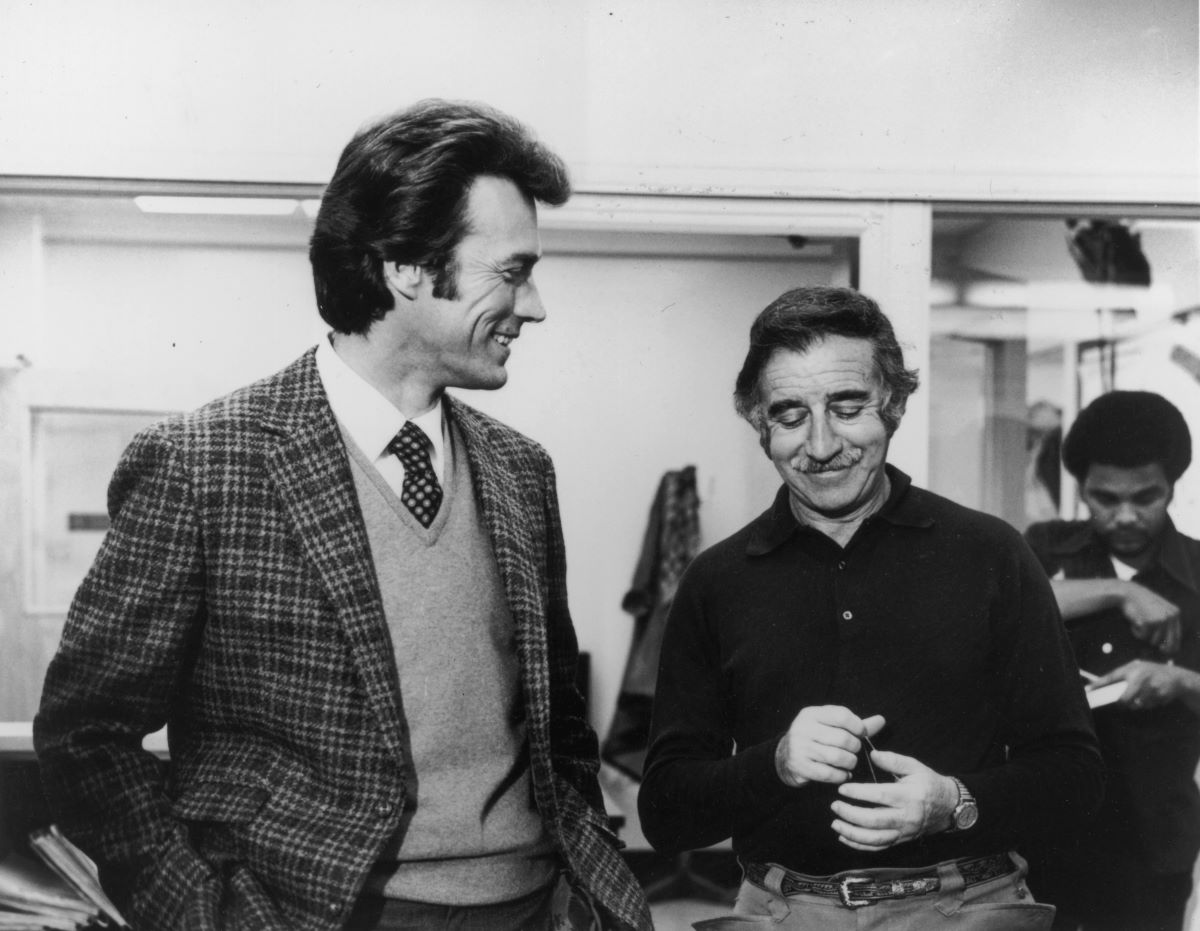

Coogan’s Bluff

Coogan’s Bluff was born out of chaos. I came on the picture in 1968, after five scripts had been written and one director had quit. I found Clint Eastwood very knowledgeable about making pictures, and very good at knowing what to do with the camera. I also found that he is inclined to underestimate himself a little as an actor, in terms of the range he can cover. Clint knows what he’s doing when he acts and when he picks material. That’s why he’s the number one box office star in the world. His character is usually bigger than life. In spite of the current mode I think people don’t really want to see pictures about mundane things and ordinary people. Clint’s character is far from mundane or ordinary. He is a tarnished super hero, actually an anti-hero. You can poke at a character like that. He makes mistakes, does things in questionable taste, is vulnerable. He’s not a white knight rescuing the girl; he seduces her.

Two Mules for Sister Sarah

There were two things in Two Mules for Sister Sarah that I’m particularly proud of. One of these things is something that I didn’t even shoot. Joe Cavalier my assistant director, took a crew into the desert to get the opening credit shots with various animals in the foreground and Clint riding in the background. I told him what I wanted and it took him two weeks to get it but it was worth it because it established a feeling for the kind of animalistic man who was our hero. It’s one of the best credit sequences I’ve seen.

I also liked the battle sequence, the attack on the fort. It involved a careful scripting of over 70 camera set-ups, from which we took about 120 shots, none of them on the screen for more than five seconds. I shot it as a montage, right out of my Warner Brothers days. I had every shot tilted in the opposite direction from the one before. I worked very hard on making that battle sequence work because there was really nothing in the story that justified it. My goal was to make it justify itself by being very exciting.

One regret I have about the picture is that it was a classic example of not getting along with the producer. 95% of my time on that picture, and most pictures which I don’t produce myself, is spent outwitting, outfoxing, and putting on an act for the producer. Marty Rackin and I did not get along. I’d make my points, but he would walk away saying: ‘I lose the battles but win the war’. The war he won on Two Mules for Sister Sarah was that he, not I, did the final editing. It’s a limited victory, however, because if you cut the picture in the camera, shoot the minimum and get to do the first cut as Alfred Hitchcock does or I do, then there isn’t that much leeway in editing the picture unless the producer orders more film shot. Normally the studio has no complaints about my shooting a minimum of film even if it upsets the producer. They grant special dispensations in such cases.

The Beguiled

The Beguiled is the best film I have done, and possibly the best I will ever do. One reason that I wanted to do the picture is that it is a woman’s picture, not a picture for women, but about them. Women are capable of deceit, larceny, murder, anything. Behind that mask of innocence lurks just as much evil as you’ll find in members of the Mafia. Any young girl, who looks perfectly harmless, is capable of murder.

There is a careful unity about the film, starting with the first frame. We begin with black and white and end with black and white; we start with Clint and the mushrooms, and end with them; we start with Clint practically dead, and end with him dead. The film is rounded, intentionally turned in on itself.

Dirty Harry

Dirty Harry is a wall-to-wall carpet of violence, and there isn’t much subtlety to it, although there are a few things in it that might escape you. It’s a simple story, basically, but physically an extremely difficult one to direct.

I took the situation as it existed without going into the raison d’etre for the killer’s action. I wasn’t interested in his background. All I was interested in was that he was a killer. Why he became a killer (the fact that his parents broke up when he was at an early age, or something like that) was left behind, because it represented dead footage for me, at least in a picture of this type.

The police have a great deal of trouble with this killer because I always like my villains to be brighter than my heroes. The killer is all by himself, and he’s quite brilliant, mysteriously so. You never quite see how he gets into or out of a place. I hold that knowledge back, so that he’s almost a cunning Superman, although not a physical one.

Dirty Harry is a bigot. He’s a bitter man. He doesn’t like people. He has no use for anyone who breaks the law, and he doesn’t like the way the law is administered. He doesn’t go for all this fol-de-rol modern method of treating criminals. This doesn’t mean I agree with him. Harry thinks that when a guy is bad you get him. You don’t worry about his rights. You don’t play with him.

Parts of this interview material are reprinted from the earlier edition but are supplemented by extracts from Movie, Positif and Don Siegel: Director by Stuart Kaminsky.

Alan Lovell

Alan Lovell, Don Siegel: American Cinema. BFI Series. British Film Institute, 1975