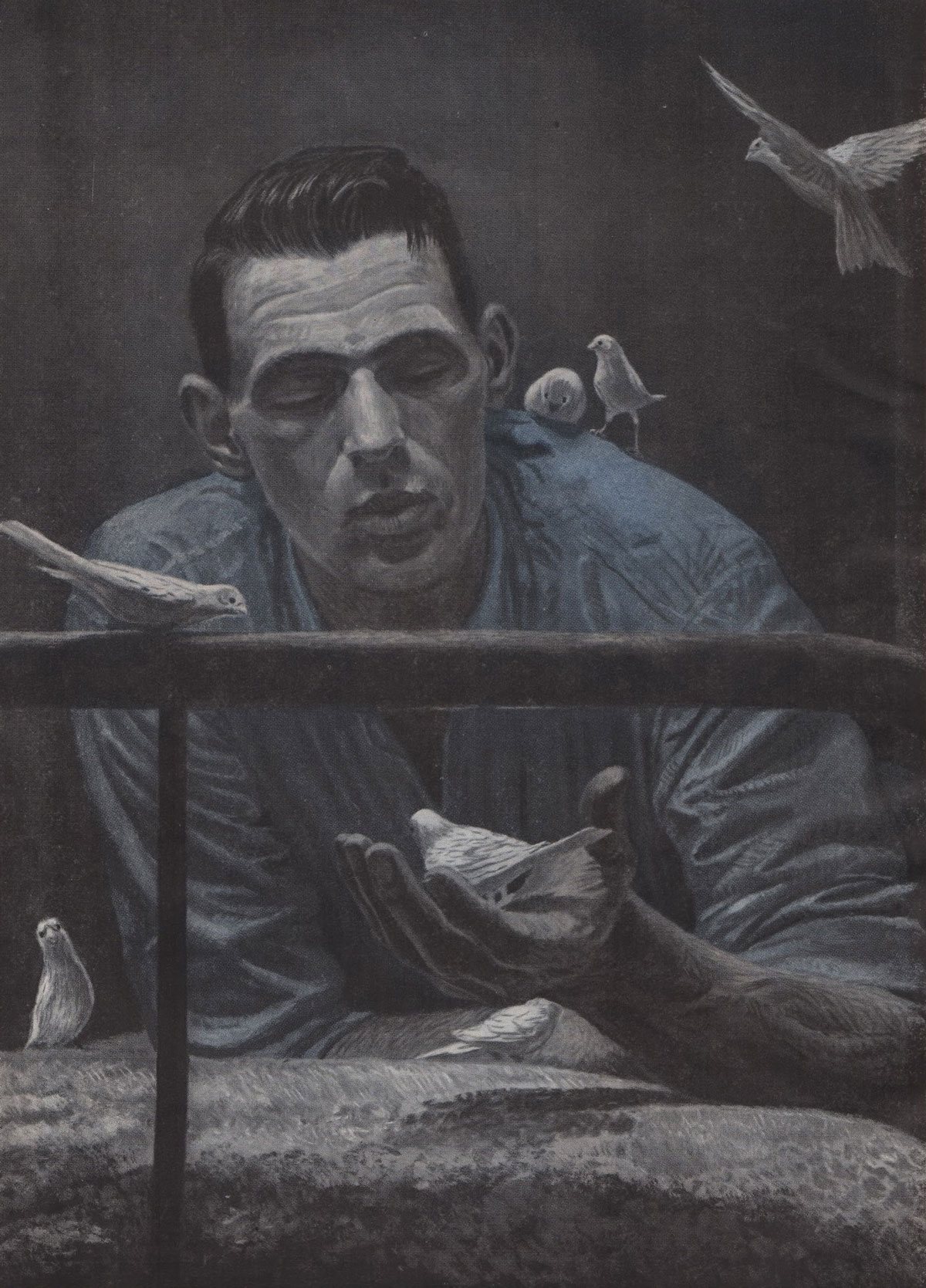

The fantastic story of a self-taught authority who has endured over half a lifetime in a solitary prison cell

by Thomas E. Gaddis

There is a man in Alcatraz who has been in isolation for thirty-seven years. This is probably longer than any other Federal prisoner has ever been kept in isolation. Steel doors shut behind Robert Stroud in 1909. Prison, in the Arabian phrase, is engraved on his eyeballs.

Robert Stroud is sixty-three, a tall old man who wears a green eyeshade cap, like an aging baseball umpire. He has a long, narrow face and penetrating blue eyes, magnified by metal-rimmed lenses. He is now six feet tall. When he went to jail, he stood six-three.

He kissed his last woman when Teddy Roosevelt was President. He has never filled out an income-tax form.

“The writer,” he said of himself in a recent court petition, “knows exactly as much about driving a car or modern traffic regulations as a Berkshire hog knows about the quantum theory. Unassisted, he would probably starve to death before he could get to the other side of the street.”

What are the memories of such a man? He has uncommon ones: He was twice sentenced to death. Once he watched his gallows being built and lived to see it torn down. At one time he had more than five hundred live canaries in his cell and was consulted by bird fanciers throughout the country as an authority on avian diseases.

No one is allowed to visit him except his brother and a prison chaplain. No one can have access to his file. He is permitted to send and receive a limited number of letters from a mailing list of three. He can have but one book at a time, and he is not permitted inside the prison library.

Stroud is in prison because he killed two men, one in 1909 and the other in 1916. The first slaying occurred in a frontier town in Alaska; the second, in a prison, with 1.200 convicts watching. Stroud denied neither. This was characteristic. From his earliest years, he has shown an almost pathological candor.

His Father Beat Him Regularly

“Robbie” Stroud was born in January, 1890, in Seattle. During his mother’s pregnancy, his father drank, kicked his wife, and took up with another woman.

When Stroud was a young boy, he was regularly thrashed by his father. But his mother lavished affection on him, even when he refused to go to school after the third grade. After one particularly severe beating when he was thirteen, Robbie fought back and tried to kill his father. Then he ran away from home, and for the next four years roamed the country.

He returned at seventeen, a tall, soft-spoken, wiry youth who knew the highways and the railroads and the flophouses of the country. His mother was overjoyed to see him, but within a few weeks a bitter quarrel broke out between father and son. Robert took off again, signed up with a railroad section gang headed for Alaska. In the gang he met another hand, a man who wanted to write about salmon. His name was Rex Beach.

He Drifted to Frontier Alaska

Stroud drifted, wound up broke in Juneau a year later. It was 1908, and the town was full of dance halls, drunken sourdoughs, and crowded cemeteries.

It was here that Stroud, at eighteen, fell into his first and only physical love affair. She was a thirty-nine-year-old prostitute. A strong, long-legged dance-hall girl with an Irish complexion and temper to match—Kitty O’Brien. Kitty returned the tough kid’s infatuation with fondness. She nursed him through a siege of pneumonia.

One fateful day, she sent him on an errand to the shack of a Russian bartender named F. K. F. Von Dahmer. He pimped for the girls at the Montana Bar, and owed Kitty some money. Kitty told her young lover to go and get it. Stroud went. Von Dahmer was found dead on the floor of his cottage. Two shots had been fired. One .38 slug was found in the cabin wall; the other was lodged in the bartender’s stomach.

Stroud appeared in the city marshal’s office. “I shot a man,” he said. The jail doors closed behind him in January, 1909. He was nineteen years old.

The gun was found in Kitty O’Brien’s room. City Marshal Mulcahy and a man named J. T. Towers testified at the preliminary hearing that Kitty had admitted to them that she had told Stroud to “go and kill the Russian.” Although Kitty testified she did not remember having such a conversation, she and Stroud were indicted for first-degree murder.

Stroud’s mother scraped together all available money and sailed for Alaska to defend her son. But the case never came to trial, because Stroud entered a plea of guilty to the lesser charge of manslaughter. Kitty O’Brien’s case was dismissed because of insufficient evidence. Stroud got twelve years, and Kitty quickly took up with someone else.

Stroud was shipped to McNeil Island Penitentiary, where he became a number with a shaved head and stripes. This was some four years before the prison-reform movement began.

After serving twenty-eight months in McNeil Island, Stroud stabbed a lifer in the shoulder during a quarrel while they were peeling potatoes. “He tried to snitch,” Stroud said. They added six months to his time. When a new cell house was completed at Leavenworth, Kansas, Stroud was tagged for the transfer.

In 1913, the prison-reform movement began. The first reform warden at Leavenworth began his term by forcing a cook to eat a quart of his own stew before firing him. Stripes were abolished. A library was installed, and correspondence courses were made available for prisoners.

Stroud’s cellmate enrolled. He had a high-school education and was considered learned. He patronized Stroud because of his third-grade schooling.

One day Stroud watched him struggling with a math assignment. “I can do that twice as fast without your education,” Stroud said.

“Why don’t you, then? Or can’t you spare the time?”

Stroud enrolled. He completed his first nine-month course in three months with a grade of A. This awakened in him a hunger for knowledge. Prison officials were amazed at the young tough who sailed through courses in astronomy and structural engineering.

But there was no indication that the prisoner’s outlook changed much as a result of his learning. The “code of the con” had soaked in. He hated the “hard-rock hotels and the screws.”

In 1915, a prison guard. Andrew Turner, was transferred from Atlanta to Leavenworth. Rumor traveled that he was considered unsafe because he had beaten a prisoner there, and so he was hated from the outset by the older convicts, among them the high-strung Stroud.

On Saturday, March 25, 1916, Stroud’s young brother, Marcus, arrived at Leavenworth, having traveled the long distance from Juneau, Alaska. Marcus asked to see Robert, but was refused because visitors were not permitted on Saturday afternoons. He left fruit and candy, and word that he had been turned away. He could, of course, return on a legitimate visiting day.

But Stroud was furious. That night he seethed and tossed. Next morning he wrote his mother, “I have been thinking all night. I can’t see any hope. I can see very little in life for either of us.”

That noon the prison band played as 1.200 cons dug into their meal. Stroud rose from his seat and approached Guard Turner. Words were exchanged, and Turner raised his club. Stroud seized the guard with one hand and drew a thin knife from his jacket. He thrust it sharply into Turner’s chest, threw the knife on the floor, and stood motionless as the dying guard sank to the floor. Stroud was hurried off into solitary.

The prisoners stirred menacingly, and guards bore down on them with upraised clubs. Twenty-six knives were found inside the prison that day, and a black river of hate boiled along the corridors.

The struggle to execute Stroud for his crime lasted four years. Stroud wrote letters immediately, but they were confiscated by the warden as evidence. Through newspaper accounts, Mrs. Stroud learned of her son’s desperate situation. She closed her rooming house in Juneau and took the next boat for the States. She hired top lawyers.

There were three complete trials. Stroud’s neck hung on what was said between him and Turner before the stabbing, since this would determine whether it was a cold, premeditated murder (first degree), one committed in the heat of passion (second-degree murder or manslaughter), or, if Turner had seriously threatened his life, a killing necessary for self-defense (justifiable homicide).

The convicts’ testimony conflicted. One prisoner testified that Stroud was “cool as a cucumber.” Another swore he was “very angry.” Five convicts were handed full pardons as they stepped to the witness stand to testify against Stroud. Stroud’s attorneys were not permitted to subpoena prisoners, though they requested the right to have nine convicts testify in behalf of Stroud.

The first trial jury found Stroud guilty of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to hang. On the basis of the judge’s instructions to the jury, a U.S. circuit court ordered a second trial.

In May, 1917, the second trial jury found him “Guilty as charged in the indictment, without capital punishment.” Again Stroud’s attorneys appealed, and again a new trial was ordered.

The third trial put Stroud’s neck in the noose. The Supreme Court affirmed the verdict and the sentence of death. Stroud’s date with the gibbet was set for April 23, 1920, in the yard of Leavenworth Prison.

The strong, set face of Elizabeth Stroud now took on added lines. Prior to the trials, her business ventures in Juneau had prospered. She had inherited $12,000 from a relative. Now, a haggard pauper, she awaited the execution of her favorite son.

He Watched His Own Gallows Built

After the final verdict, Stroud was returned to a solitary cell at Leavenworth. One morning in the spring of 1920, he heard the sound of a saw biting through wood outside his cell. Through the bars he spotted a trusty sawing planks. Stroud hissed through the bars, but the trusty ignored him.

Stroud got word through the prison grapevine for the trusty to walk nearer his cell. He came by the next day.

“You’re building it,” Stroud said.

“For you, Bob. Tailor-made.”

Stroud grinned. “That thing will never drop me.”

Later, Stroud watched them test the gallows with a sandbag. This grisly experiment made him stare deeply into himself. “The doomed man.” he later wrote, “found the defect within himself that made him kill, and having found it, now took steps to correct it and rebuild his life on constructive lines, even while he listened to the construction of his gallows.” He claims he has never attempted violence since.

Ten days before the execution date, Elizabeth Stroud borrowed some money for a last desperate effort to save her son’s life. She went to Washington. D.C., and because her family was well known in Illinois, got a hearing with ex-Senator J. Ham Lewis of Illinois. Through the senator’s efforts, she was able to talk to President Wilson’s secretary, and finally to Mrs. Wilson herself. Later, Mrs. Wilson went into the sickroom where the President lay, and a few minutes later came out with a piece of paper. On it was scrawled in a trembling hand, “Robert Stroud commuted to life imprisonment. W. W.”

He’s Treated As a Vicious Man

Since the day he killed the prison guard, Robert Stroud has been treated as a vicious and dangerous man. He has been confined to a solitary cell, never permitted to mingle with other prisoners.

Stroud’s letters after the trials revealed the effects of his near escape from death. He showed a strong sense of living on borrowed time. He felt a deep obligation to his mother, and tried to support her by painting Christmas cards and, later, pictures. He worked for two years, but his eyesight began to fail, and he abandoned the project.

Two ironical events followed: His mother got a job in a casket factory at twelve dollars a week. His younger brother changed his name to L. G. Marcus, entered vaudeville, and became The Great Marcus, The Great Escape Artist.

A new prison administration at Leavenworth took note of Stroud’s weakening eyes and physical condition. They installed brighter lighting and allowed the prisoner exercise and fresh air in a walled-in section of the yard adjoining the isolation building. A lone figure with his individual allotment of light and air, he took to playing handball.

One day he saw something tiny move in a corner of the yard. He blinked, got closer, and saw it was a young sparrow with a broken wing. He got a match-stick and a strip of cloth and made a splint for the sparrow. By the time it was well, it had grown tame.

A month later, he asked to see the deputy warden, who was known to be a bird lover.

“This is Jerry,” Stroud said. “Jerry, play dead.” The sparrow rolled over on his back and lay stiff. The warden’s eyes widened.

“Wake up, Jerry! Stroud ordered the bird. Jerry came to life and hopped on his shoulder.

“How did you get him to play dead?” the warden asked.

“It takes time. I’ve got plenty of that, you know,” replied Stroud.

The deputy warden grinned. “All right. You can keep the bird.”

Later a prisoner who had been given a pair of canaries asked permission to turn them over to Stroud. It was granted.

Stroud begged a wooden soapbox from a guard, brought a stolen razor blade from hiding, and went to work. He took apart the boxes, saving the nails, and then fashioned a bird cage. His mother brought bird foods and medicines to him, and his brother sent money. Soon there were eggs, then canary chicks. He got pop bottles from the guards, and he broke them off an inch from the bottom, then rubbed them against the stone of his cell until the glass became smooth. Now he had water and feed cups for his birds. A year later, the solitary cell block at Leavenworth echoed with the song of a score of roller canaries.

Stroud was permitted to subscribe to leading bird journals, and his brother sent him books. The guards helped him build wire cages. Soon he was shipping healthy warblers to his mother, who became his agent, handling the sales of the birds for him. His dream of supporting her from prison came true.

He Studied to Save His Birds

One day, two of Stroud’s canaries died. Next day, most of his birds lay lifeless on the floors of their cages.

In panic, Stroud appealed for books on bird diseases. He wrote to universities, secured books on avian anatomy and pathology. He discovered how little was known, and his desperation increased.

“I began to fight,” he wrote former prison official William I. Biddle, then city editor of the Leavenworth Times. “No longer did I kill birds to stop the spread of the disease. They were permitted to die, were carefully dissected, and my mind, free from all thought of personal loss or other emotions, worked twenty-four hours a day to weave these facts, ideas, and observations into logical theories. It was a wild brand of logic, often based upon half-guessed truths. . . . No bacteriologist or doctor would ever have tried the things I did. But one of them worked.”

Stroud had discovered how to keep his birds alive.

An oral agreement reportedly took place between the warden of Leavenworth and Stroud. Stroud was given wide mailing and correspondence privileges, including publication of his writings in bird journals, provided he would not reveal that he was a prisoner. He was permitted to have a typewriter to answer his heavy mail.

Bird breeders began writing him for information about his canary cure, and they sought his advice on other problems. The Roller Canary Journal, the All-Pets Magazine, and other bird periodicals soon carried articles with the by-line Robert Stroud, Box 7, Leavenworth, Kansas. The low post-office box number sounded like a large established address (it was!), and none of the readers could have had the slightest idea that the scholarly articles were written in a prison cell. Stroud’s articles were titled “Hemorrhagic Septicemia in Canaries,” “Specific Treatment for Septic Fever,” and “Psittacosis Data.”

E. J. Powell, editor of the Roller Canary Journal, stated, “Stroud’s articles are the finest I have ever read. I have received requests for reprints from as far as England.” He later published Stroud’s first book, Diseases of Canaries.

A former official tells how Stroud took part in a stunt that helped boost his earnings and bolstered the prison’s public relations. Touring visitors would approach the isolation section, and the guide would lower his voice to tell about the murderous past of “this Stroud” and how no one dared go near him. Then, like tossing meat to a caged lion, the guard would flip a pack of cigarettes at Stroud. Stroud would glare and snarl convincingly. Then, to illustrate the prison’s humane treatment, the guard would point to the books and the birds. The visitors, impressed, would buy souvenirs and birds from “Stroud the Desperado.”

One day in 1930, an Indiana widow named Della Jones opened her favorite magazine, a bird journal. Her pet songster had just died, and so she read with special interest a technical article on septicemia by one Robert F. Stroud.

Later, the bird journal announced a contest for the finest mothering technique and best ability to care for nestlings, and Mrs. Jones offered one of her own canaries as a prize.

She was pleased to learn that the contest winner was the scholarly bird authority, Robert F. Stroud. She thought he must be a modest college professor. She could not ship a prize canary to a post-office box that he gave as his address, so she wrote requesting a better address.

A Bizarre “Marriage” for Stroud

Della was shocked—but intrigued—to learn that Stroud was a convict. She began to correspond with him, and in April, 1931, visited Leavenworth Prison. A series of meetings ensued, and she and Stroud decided to go into business together. She moved to Kansas City.

Then, in a bizarre manner, Stroud and Della were “married.” They drew up a contract stating that each to the other was “everything that a true, loving, and faithful spouse can possibly be,” and signed it, and Della filed it in the office of the Recorder of Deeds of Leavenworth County, Kansas, on August 15, 1933.

Now in his early forties, Stroud had acquired hope and a goal. His cell was banked from floor to ceiling with labeled cages containing hundreds of canaries, including a new crested warbler he had originated. Every inch of space was crowded with medicines, technical books, and bird foods. He was piling up years of good behavior as a prisoner. He was supporting his mother. He felt of value as an aid to hundreds of bird lovers.

His letters of this period reveal his conviction that he had put his time to good use. He began to hope for parole.

Meanwhile, the new Federal Bureau of Prisons had been created in Washington. In 1930, it brought central control and common standards to the mushrooming Federal prison population. An order was issued prohibiting prisoners from conducting business, and Stroud was ordered to give up his birds and discontinue his business within sixty days.

He began a frantic struggle to keep his birds. Della, despite Stroud’s agreement not to reveal his status as a prisoner, wrote an article for a bird publication disclosing his identity, and canary raisers rushed to his aid.

It was during jobless 1931, and people were restless and angry. Congressmen made protests to the startled Federal Bureau of Prisons. Thousands of signatures were affixed to petitions on Stroud’s behalf and sent to President Hoover.

The pressure worked. The bureau’s director disclosed that the order did not really apply to Stroud after all. Stroud was given an adjoining cell for his birds. Specialists checked his eyes. Kansas Wesleyan University donated a microscope and slides. Laboratory equipment was made available. It was revealed Stroud would be up for parole in 1937.

But public interest waned. Prison authorities offered Stroud a plan whereby he would continue to raise birds, but the profits would be turned over to a prison welfare fund, except for a small wage for Stroud. Stroud turned down the offer, and his special mailing privileges were withdrawn. His correspondence dropped from sixty letters a week to the prison standard of two. Bird breeders who wrote received no answer, and they lost interest. As a result, Stroud’s curious prison enterprise died.

Meanwhile, Stroud continued his experiments. He summed up his findings in a manuscript illustrated by painstaking drawings.

When Stroud’s application for parole came up in 1937, it was denied.

After Stroud’s “marriage,” friction had developed between his mother and Della Jones. After his parole failed to materialize, Della gradually lost interest. The failure of his bird business broke the only tie between them, and she drifted out of his life.

Elizabeth Stroud now began to complain that she felt very tired. Within the year, she died.

These were terrible blows for the aging convict. But despite them, he completed Stroud’s Digest of the Diseases of Birds, now a standard work, in 1942.

Prison officials, meanwhile, were displeased. They said Stroud used his laboratory glassware to make hooch in, and complained that his birds were dirty.

One day, the week before Christmas in 1942, two guards brusquely opened the door of his cell.

“Let’s go,” said one guard.

“Where?” Stroud asked, startled.

“You’re getting your Christmas on the Rock.”

Stroud looked at his birds for the last time, then walked from his cell, his face stone-hard.

His Role in the Alcatraz Riot

Stroud was transferred to Alcatraz, officials explained, because he had broken prison rules at Leavenworth. At Alcatraz, he was lodged in D Block, a segregated section for convicts considered too dangerous to mingle with other prisoners.

Stroud, now fifty-three, began to study law.

In 1946, hell broke loose on the Rock. A quintet of dangerous convicts set off one of the worst riots in the history of Federal prisons. One of their first moves was to unlock some cells in D Block.

The warden of Alcatraz, James A. Johnston, reasoned that the armed convicts were holed up in D Block. Stroud cried out to the guards. “There are no guns in D Block,” and then risked his life in a vain attempt to get recognized as a peaceful spokesman for the prisoners of D Block.

But Warden Johnston was taking no chances. For hours, Stroud and nine other prisoners huddled on their cell floors behind a barricade of mattresses and books while bullets, grenades, phosphorus bombs, and tank shells exploded in D Block. Finally the deadly barrage lifted. Some of Stroud’s books and writings were destroyed, but he was not injured.

In March, 1950, as a result of a petition he made to a Federal court, he revealed the existence of a 350,000-word manuscript detailing his life in Federal prisons since 1909. He has not been permitted to release this manuscript.

For a while, Stroud was given special book privileges. But prison officials said that his cell floor was cluttered with open books, making too much work for the orderly who cleaned his cell, and withdrew his extra privileges.

In May, 1951, an Iowa bird lover wrote the Federal Bureau of Prisons, citing Stroud’s work, and inquired whether he was still considered dangerous.

“It is undoubtedly true,” answered A. H. Conner, acting director, “that Stroud’s work on the diseases of birds has been most helpful to the bird breeders of the world. It is most unfortunate that his adjustment in our care degenerated so that it became necessary to transfer him to the prison at Alcatraz. . . . The U. S. Board of Parole has considered his application for parole on a number of occasions, but has not indicated that he is ready for release to the community.”

Despite his Promethean endurance, a querulous note began to creep into his letters in 1951. After an intense gallbladder attack he wrote, “You can’t imagine how it is to fight for every ounce of energy to do with, and what that means year after year, being stimulated to hope and then let down to despair. . . . I believed I deserved it [a pardon] for the good I had done, but I wanted it on merit or not at all. The only things I had left were my mental and moral integrity, and there was no reward that could ever induce me to compromise.”

He Tried to Kill Himself

Around Christmas. 1951, the prisoner swallowed an overdose of barbital pills. He was discovered and given swift emergency treatment. When his stomach was pumped, its contents yielded a sealed tube. Inside the tube were instructions to the coroner to place his story of Federal prison life before the public.

Now Stroud stares into his forty-fifth year of imprisonment, and his thirty-eighth year of isolation. He still hopes, still dreams. He hopes the President may choose to intervene in his curious life. He dreams of making a ten-acre sanctuary for birds, if a pardon comes.

He does not know the real name for Alcatraz. It is the Isla de Los Alcatraces, or Island of Pelicans. They used to call it Bird Island.

THE END

Source: Cosmopolitan, May 1953; pp. 68-73