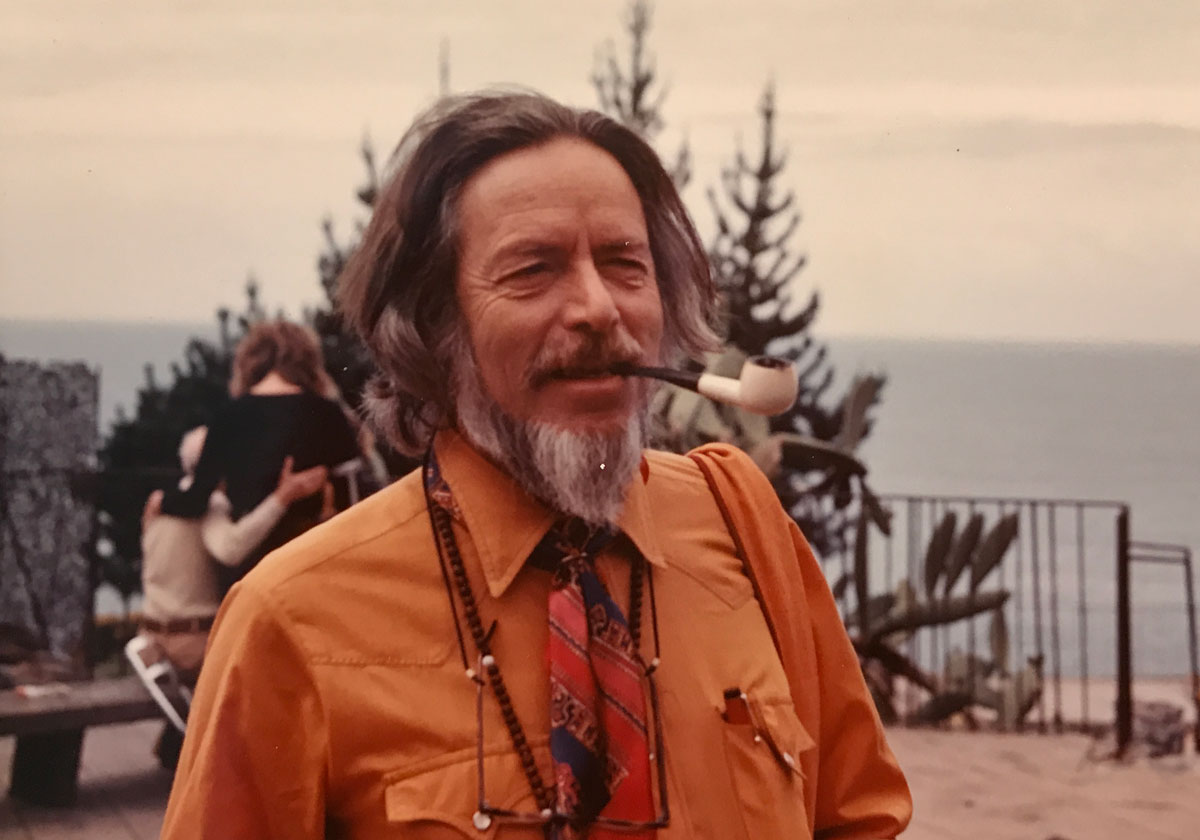

by Alan Watts

I want to talk to you a bit about the general purpose of this tour. I might say that I’m interested in Japanese materialism, because contrary to popular belief, Americans are not materialists. We are not people who love material, but our culture is by and large, devoted to the transformation of material into junk, as rapidly as possible. God’s own junkyard! And therefore it’s a very, very important lesson for a wealthy nation, and for a rich people. And we are all colossally rich by the standards of the rest of the world. It’s very important for such people to learn and see what happens to material in the hands of people who love it.

And so, you might say that in Japan, and in China, but in Japan in a peculiar way, the underlying philosophy of life is a spiritual materialism. There is not the divorce between soul and body, between spirit and matter, between spirit and nature, or God and nature, which there is in the West. And therefore, there is not the same kind of contempt for material things. We regard matter as something that gets in our way, something whose limitations are to be abolished as fast as possible, and therefore we have bulldozers and every kind of technical device for knocking it out of the way. And we like to do as much obliteration of time and space as possible. We talk about killing time, and getting there as fast as possible, but of course, as you notice in Tokyo, and as your noticing here, the nearer it gets to you by time, by the abolition of distance, the more it’s the same place from which you started.

This is one of the great difficulties—what is going to happen to this city, and this country when it becomes the same place as California. In the same way, in other words, you could take a streetcar from one end of town to another, and it’s the same town. So, if you can take a jet plane from one city to another (and everybody’s doing it, not just the privileged few), then they’re going to be the same town.

So, to preserve the whole world from indefinite Los Angelization, pardon me, those of you from Southern California, but, we have to learn in the United States, how to enjoy material, and to be true materialists, instead of exploiters of material. And so, this is the main reason for going into philosophy of the Far East, and how it relates to every day life—to architecture, to gardens, to clothes, and to the higher arts of painting, tea ceremony, music, sculpture, ritual, and so on.

Well now, basic to all this is the philosophy of nature. And the Japanese philosophy of nature is probably founded historically in the Chinese philosophy of nature, and that’s what I want to go into to start with. To let the cat out of the bag, right at the beginning, the assumptions underlying Far Eastern culture, (and this is true as far west as India, also) is that the whole cosmos, the whole universe, is one being.

It is not a collection of many different beings, who somehow floated together like alot of flotsam and jetsam from the ends of space, and ended up as a thing called the universe. They look at the world as one, eternal activity, and that’s the only real self that you have. You are theworks—only what we call you, as a distinct organism, is simply a manifestation of the whole thing. Just as the ocean when it waves, it’s the whole ocean waving when it waves. And the whole ocean, when it waves, it says, “Yoo-Hoo, I’m here!”, you see. So each one of us is a wave of all that there is, of the whole works. And they don’t, you see this is, in this culture, not something that is just a theory—not just an idea, like you would have, I have my ideas, you have your ideas, in other words, you’re a Christian Scientist, I’m a Baptist, or something like that. No, or I’m a Republican, and you’re a Democrat, and I’m a Bircher, and you’re a communist. It isn’t that kind of thing—it’s not an opinion, it’s a feeling.

And so, the great, the great men of this culture (not everybody), but the great men, the great masters, of whatever sphere they’re in, are fundamentally of this feeling that what you are is the thing that always was, is and will be, only it’s playing the game called, “Mr. Tocano,” or “Mr. Lee,” or “Mr. Mukapadya.” That’s a special game it’s playing, just like there’s the fish game, the grass game, the bamboo game, the pine tree game, they’re all ways of going “Hoochie-koochie-doochie-doochie-doochie-doo.” You see everything’s doing a dance, only it’s doing it according to the nature of the dance. The universe is fundamentally all these dances, whether human, fish, bird, cloud, sky dance, star dance, etc., they are all one fundamental dance. Or dancer. Only in Chinese, you don’t distinguish the subject from the verb, I mean, you don’t distinguish the noun from the verb in the same way that we do. A noun can become a verb, a verb can become a noun. But, that’s the business.

A civilized, cultured, above all, an enlightened person, in this culture, is one who knows that his so-called “separate personality,” his ego, is an illusion. Illusion doesn’t mean a bad thing, it just means a play, from the Latin word, ludere, we get English illusion. Ludere means to play. So, the Sanskrit word, maya, meaning illusion, also means magic, skill, art, and this Sanskrit conception comes through China to Japan with the transmission of Buddhism.

The world as a Maya, or sometimes as it’s called in Sanskrit: lila, (our word ‘lilt’); Lila, is play. So, all individual manifestations are games, dances, symphonies, musical forms, being put on by the whole show. And everyone is basically the whole show, so that’s the fundamental feeling.

But Nature, Nature as the word is used in the Far East doesn’t mean quite the same as the word Nature in the West. In Chinese, nature, the word we translate nature, zitran, or in Japanese, shizen, is made up of two characters. That first one means “of itself,” and the second one means “so”. What is so, of itself. This is a rather difficult word to translate well into English. We might say, automatic,” but automatic suggests something mechanical.

When a Chinese coolie was supposed to have seen a tram car for the first time, he said, “No pushee, no pulley, go like mad!” But, uh, this mechanical idea of the automatic won’t properly translate this word zitran, in Chinese, shizen in Japanese. Of itself so, what happens, or as we say, what comes naturally. It’s in that sense of our word nature, to be natural, to act in accordance with one’s nature, not to strive for things, not to force things, that they use the word natural. So, when your hair grows, it grows without your telling it to, and you don’t have to force it to grow. So, in the same way, when the color of your eyes, whether it’s blue or brown, or whatever, the eyes color themselves, and you don’t tell them how to do it. When your bones grow a certain way, they do it all of themselves.

And so, in the same way, I remember a Zen master once, he was a beautiful man, he used to teach in New York. His name was Mr. Sazaki. One evening, he was sitting in his golden robes, in a very formal throne-like chair, with a fan in his hand, he had one of those fly-whisks made of a white horse’s tail. And he was looking very, very dignified—incense burning on the table in front of him, there was a little desk with one of the scriptures on it that he was explaining. And he said, “All nature has no purpose. Purposelessness most fundamental principle of Buddhism, purposelessness. Ahhh, when you drop fart, you don’t say, ‘At nine o’clock I dropped fart,’ it just happen.’ ”

So then, it’s fundamental to this idea of nature, that the world has no boss. In, this is very important, especially if you’re going to understand Shinto. Because, we translate, kami, or shin as God, but it’s not God in that sense. God, in much of the Western meaning of the word, means “the controller,” “the boss of the world.” And the model that we use for nature tends to be the model of the carpenter, or the potter, or the king. That, just as the carpenter takes wood and makes a table out of it, or as the potter takes inert clay, and with the intelligence of his hands evokes a form in it, or as the king is the law-giver who, from above, tells people what order they shall move in, and how they shall behave, it is ingrained into the Western mind to think that the universe is a behavior which is responding to somebody in charge, and understands it all.

When I was a little boy, and I used to ask my mother many questions, sometimes she’d get fed up with me, and say, “My dear, there are some things in this life that we are not just meant to know.” And so I said, “Well, what about it? Will we ever know?” “Well,” she said, “yes, when you die, and you go to Heaven, God will make it all clear.”

And I used to think, that maybe, on wet afternoons in Heaven, we’d all sit around God’s throne and say, “Heavenly Father, why are the leaves green?” And he would say, “Because of the chlorophyll!” And we would say, “Oh!”.

Well, that idea, you see, of the world as an artifact could prompt a child in our culture to say to it’s mother, “How was I made?” And it seems very natural. So when it’s explained that God made you, the child naturally goes on and says, “But who made God?” But, I don’t think a Chinese child would ask that question at all, “How was I made?” Because the Chinese mind does not look at the world of nature as something manufactured, but rather grown.

The character for coming into being in Chinese is based on a symbol of a growing plant. Now growing and making are two different things. When you make something, you assemble parts, or you take a piece of wood and you carve it, working gradually from the outside inwards, cutting away until you’ve got the shape you want. But when you watch something grow, it isn’t going like that.

If you see, for example, a fast motion movie of a rose growing, you will see that the process goes from the inside to the outside—it is, as it were, something expanding from the center. And that, so far from being an addition of parts, it all grows together, all moves all over itself at once. And the same is true when you’re watching the formation of crystals, or even if you’re watching a photographic plate being developed. Suddenly, all over the area of the plate, over the field, shall we call it, like a magnetic field, it all arises.

That idea of the world as growing, and as not obeying any laws, because there is in Chinese philosophy no difference between the Tao (that is the word t-a-o), the Japanese do, there is—no difference between the Way, the power of Nature, and the things in Nature.

It isn’t, you see, when I stir up wind with this fan, it isn’t simply that the wind obeys the fan. There wouldn’t be a fan in my hand unless there were wind around. Unless there were air, no fan. So the air brings the fan into being as much as the fan brings the air into being. So, they don’t think in this way of obeying all the time— masters and slaves, lord and servant.

Lao-Tse, who is supposed to have written the Tao Te Ching, the fundamental book of the Taoist philosophy, lived probably, a little before 300 B.C. Although tradition makes him a contemporary of Confucius, who lived closer to 600, he says in his book, “The great Tao flows everywhere, to the left and to the right. It loves and nourishes all things, but does not lord it over them. And when merits are attained, it makes no claim to them.”

The corollary of that is, that if this is the way nature is run, not by government, but by, as it were, letting everything follow its course, then the skillful man or woman, or the skillful ruler, or the sage interferes as little as possible with the course of things. Of course you can’t help interfering. Every time you look at something, you change it. Your existence is, in a way, an interference, but if you think of yourself as something separate from the rest of the world, then you will think of interference or not-interference. But if you know that you’re not separate from it, that you are just as much in and of nature as the wind or the clouds, then who interferes with them?

In general, the notion is that life is most skillfully lived when one sails a boat, rather than rowing it. You see it’s more intelligent to sail than to row. With oars I have to use my muscles and my effort to drag myself along the water, but with a sail, I let the wind do the work for me. More skillful still, when I learn to tack, and let the wind blow me against the direction of the wind. Now, that’s the whole philosophy of the Tao. It’s called in Chinese, wu-wei, wu-non, wei—striving. Mui is Japanese at pronouncing the Chinese wei. Mu is Chinese wu. Mui, as distinct from ui. Ui means to use effort—to go against the grain, to force things. Mui—not to go against the grain, to go with the grain.

And so, you will see around you, in every direction, examples of mui—of the intelligent handling of nature, so as to go with it rather than against it. For example, the famous art of Judo is entirely based on this. When you are attacked, don’t simply oppose the force used against you, but go in the same direction as it’s going, and lead it to its own downfall.

So it is said, in the winter, there’s a tough pine tree, which has a branch like this, and muscles. And the snow piles up and piles up, and this unyielding branch eventually has this huge weight of snow, and it cracks. Whereas the willow tree has a springy, supple branch, and a little snow comes on it, and the branch just goes down, and the snow falls off, and whoops, the branch goes up again.

Lao-Tse said, “Man, at his birth is supple and tender, but in death, he is rigid and hard. Plants when they are young, are soft and supple, but in death they are brittle and hard. So, suppleness and tenderness are the characteristics of life, and rigidity and hardness the characteristics of death.” He made many references to water. He said, “Of all things in the world, nothing is more soft than water, and yet it wears away the hardest rocks. Furthermore, water is humble, it always seeks the low level, which men abhor. But yet, water finally overcomes everything.”

When you watch water take the line of least resistance, you watch for example, water poured out on the ground, then you see it, as it were, ejecting fingers from itself, and some of those fingers stop. But, one finger goes on—it’s found the lowest level. Now, you say, “Oh, but that’s not the water, the water didn’t do anything, that’s just the contours of the land, and because of the contours of the land, the water goes where the land makes it go.” Think again.

Does the sailing boat go where the wind makes it go? I never forget once, I was out in the countryside, and a piece of thistle-down flew out of the blue. It came right down near me, and I put out a finger, and I caught it by one of its little tendrils. And it behaved just like catching a daddy long-legs, you know, when you catch one by one leg it naturally struggles to get away. Well, this thing behaved just like that, and I thought well, “It was just the wind doing that, it only appears to look as if it was doing it.” Then I thought again, “Wait a minute! It is the wind, yes, but, it’s also that this has the intelligence to grow itself, so as to use the wind.” You see that? That is intelligence. That little structure of thistle-down is a form of intelligence, just as surely, as the construction of a house is a manifestation of intelligence. But it uses the wind.

In the same way, the water uses the conformations of the ground. Water isn’t just dead stuff. It’s not just being pushed around. Nothing is being pushed around in the Chinese view of nature. Because you see, my first point as I’ve been saying, is what they mean by nature; that it is something that happens of itself—that it has no boss. The second point is that it does not. In the sense that it doesn’t have a boss, somebody giving orders, somebody obeying orders, that leads further to an entirely different conception of cause and effect. Cause and effect is based on giving orders. When you say, “Something made this happen.” It had to happen because of what happened before. The Chinese don’t think like that. His idea of causality is called, or the concept which does duty for our idea of causality is called “mutual arsing.”

Let’s take the relationship between the back and the front of anything. Is the back the cause of the front, or is the front the cause of the back? What a silly question! If things don’t have fronts, then they can’t have backs. If they don’t have backs, they can’t have fronts. Front and back always go together, that is to say, they come into being together. And so, in just the same way as the front and the back arise together, the basic sort of Chinese Taoist philosophy sees everything in the world coming together.

This is called the Philosophy of Mutual Interpenetration. In Japanese, gi-gi-muge. We’ll go into this in detail when we get to nara, because nara is the center of Kegon Buddhism, and so, this is the particular philosophy which developed gi-gi-muge. But still, it goes way back into the history of the Chinese idea of nature.

Now look at it very simply. Let us suppose that you had never seen a cat, and one day you were looking through a very narrow slit in a fence, and a cat walks by. First you see the cat’s head, then there’s a rather nondescript fuzzy interval, and a tail follows. And you say, “Marvelous!” Then the cat turns ’round and walks back. You see the head, and then after a little interval, the tail. You say, “Incredible!” The cat turns around and walks back again, and you see first the head, and then the tail, and you say, “This begins to look like a regularity, there must be some order in this phenomenon, because whenever I see the thing which I’ve labelled head, I later see the thing I’ve labelled tail.”

Therefore, where there is an event which I call head, and it’s invariably followed by another event that I call tail, obviously head is the cause of tail, and the tail is the effect. Now, we think that way about everything. But of course, if you suddenly widened up the crack in the fence, so that you saw that the head and the tail were all one cat, and that the head, and when a cat is born, it’s born with a head and a tail, it isn’t that there is a head, and then later, a tail.

So, in exactly the same way, the events that we seem to call, “separate events,” are really all one event, only we chop it into pieces to describe it. Like we say, “The head of the cat, and the tail of the cat,” although it’s all one cat. When we’ve chopped it to pieces, then we suddenly forget we did that, and try to explain how they fit together—and we invent a myth called “causality” to explain how they do. The reason we chop the world into bits is simply for purposes of intellectual convenience.

For example, our world is through and through wiggly, and you notice that very much, how these people, although they have models, symmetry and use of space in the construction of houses, they love wigglings and their garden, you see, is very fundamentally wiggly. They appreciate wiggly rocks. I remember so much as a child, wondering why Chinese houses all had wiggly roofs, the way they were curved. And why the people looked more wiggly than our people look. Cause the world is wiggly! Now, what are you gonna do with a wiggly world? You’ve gotta straighten it out! So we notice that the initial solution is to try and straighten it out.

People, of course, are very wiggly indeed. Only because we all appear together, do we look regular. You know, we have two eyes, one nose, one mouth, and two ears, and so on… We look regular so we make sense. But if somebody had never seen a person before, they’d say, “What’s this extraordinary, amazing, wiggly phenomenon?” We are—the world is—wiggly.

One of the wiggliest things in the world is a fish. Somebody once found out they could use a net and catch a fish. Then they thought out a much better idea than that—they could catch the world with a net. A wiggly world. But what happens? Hang up a net in front of the world and look through it. What happens? You can count the wiggles, by saying, this wiggle goes so many holes across, so many holes down, so many holes across, so many to the left, so many to the right, so many up, so many down… What do you have? You have the genesis of the calculus. And your net, as it were, breaks up the world into countable bits, as we now say in information theory, “We have so many bits of information to process.”

In the same way, a bit is a bite. You go to eat chicken, you can’t swallow the whole chicken at once, so you’ve got to take it in bites. But you don’t get a cut up fryer out of the egg. So in the same way the real universe has no bits. It’s all one thing, it’s noc alot of things. In order to digest it with your mind, which thinks of one thing at a time, you’ve got to make a calculus, you’ve got to chop the universe into bits, so as to think about it, and talk about it.

You can see this whole fan at once, but if you want to talk about it, you have to talk about it bit by bit. Describe it, go into the details. What details? Well, so with the world. If you don’t realize that’s what you’ve done, that you’ve ‘bitted’ the world in order to think about it, it isn’t really bitted at all. If you don’t realize that, then you have troubles, because then you’ve got to explain how the bits go together. How they connect with each other— so you invent all sorts of ghosts, called “Cause and Effect”, and influences. The word influence, you know— How do I influence you? As if I was something different from you. So influences, and ghosts and spooks, all these things come into being if we forget that we made the initial step of breaking the unity into pieces in order to discuss it.

So then, stepping back again, we have these very, very basic principles then. The world as nature, what happens of itself, is looked upon as a living organism, and it doesn’t have a boss because things are not behaving in response to something that pushes them around. They are just behaving. And it’s all one, big behavior. Only if you want to look at it from certain points of view, you can see it as if something else were making something happen. But you do that only because you divide the thing up.

“So now,” you say, “final question. Is their nature chaotic? Is there no law around here?” There is not one single Chinese word that means the Law of Nature, as we use it. The only word in Chinese that means law as we use it is a word tse, and this word is a character which represents a cauldron with a knife beside it. And this goes back to the fact that in very ancient times, when a certain emperor made laws for the people, he had the laws etched on the sacrificial cauldrons, so that when the people brought the sacrifices they would read what was written on the cauldrons. And so this word, tse. But the sages, who were of a Taoist feeling at the time that this emperor lived said, “You shouldn’t have done that, sir. Because the moment the people know what the law is, they develop a little dis-spirit. And they’ll say, ’Well now, did you mean this precisely, did you mean that precisely. And we’ll find a way of wrangling around it.’ ” So they said that the nature of nature, Tao, is wut-se, which means lawless, but in that sense of law.

But to say that nature is lawless is not to say that it’s chaotic. Now the Chinese word here for the order of nature is called in Japanese ri, Chinese li. Ri, is a curious word, it originally meant “the markings in jade, the grain in wood, or the fibre in muscle.” Now when you look at jade, you see it has this wonderful, mottled markings in it. And you know, somehow and you can’t explain why, those mottlings are not chaotic. When you look at the patterns of clouds, or the patterns of foam on the water, isn’t it astounding, they never, never make an aesthetic mistake.

Look at the way the stars are arranged, or they’re not arranged! They’re just like, they seem to be scattered through the sky like spray. But would you ever criticize the stars for being in poor taste? When you look at a mountain range—it’s perfect. But somehow, this spontaneous, wiggly arrangement of nature is quite different from anything we would call a mess.

Look at an ashtray, full of cigarette butts and screwed bits of paper. Look at some modern painting, where people have gone out of their way to create the expensive messes. You see, they’re different. And this is the joke, that we can’t put our finger on what the difference is, although we jolly well know it. We can’t define it. If we could define it… in other words, if we could define aesthetic beauty, it would cease to be interesting. In other words, if we could have a method that would automatically produce great artists, anybody could go to school and become a great artist. Their work would be the most boring kind of kittsch. But just because you don’t know how it’s done, that gives it an excitement.

And so it is with this. There is no formula, that is to say, no tse—no rule according to which all this happens. And yet it’s not a mess. So this idea of ri, (you can translate the word ri as organic pattern). And this ri is the word that they use for the order of nature, instead of our idea of law, where the things are obeying something. If they are not obeying a governor, in the sense of God, they are obeying principles, like a streetcar. Do you know that limerick?

There was a young man who said, “Damn!”

For it certainly seems that I am

A creature that moves, in determinate grooves

I’m not even a bus, I’m a tram!

So that idea of the iron rails, along which the course of life goes is absent here. And that is why basically, this accounts for Chinese and Japanese humanism. And here (this is very important), there’s a basic humanism to this culture. The people in this culture, Chinese and Japanese don’t feel guilty ever. They feel ashamed, yes., of something. Ashamed because they have transgressed social requirements. But they are incapable of a sense of

“Sin”. They don’t feel, in other words that you are guilty because you exist, you owe your existence to the Lord God, and you were a mistake anyway! You know? They don’t feel that. They have social shame, but not metaphysical guilt, and that leads to a great relaxation. And you can sense it if you’re sensitive, just walking around the streets. You realize that these people have not been tarred with that terrible monotheistic brush which gives them the sense of guilt.

They work on the supposition that human nature, like all nature is basically good. It consists in it’s good-bad. It consists in the passions as much as the virtues. In Chinese there’s a word un. I don’t know how it’s pronounced in Japanese. I’ll write it backwards. How do pronounce that in Japanese? This means humanheartedness, humane-ness. Not in the sense of being humane in the sense of being kind necessarily, but of being human. So I’say, “Oh, he’s a great human being,” means that’s the kind of person who’s not a stuffed shirt, who is able to come off it, who can talk with you on a man-to-man basis, who recognizes along with you that he is a rascal, too. And so people, men for example, when they each affectionately call a friend of theirs, “Hi, you old bastard, how you getting on?” This is a term of endearment, because they know that he shares with them what I call the “Element of Irreducible Rascality”—that we all have.

So then, if a person has this attitude, he is never going to be an over-weaning goody-goody. Confucius said, “Goody-goodies are the thieves of virtue.” Because you see, if I am right, then you are wrong. And we get into a fight. What I am is a crusader against the wrong, and I’m going to obliterate you, or I’m going to demand your unconditional surrender. But if I say, “No, I’m not right, and you’re not wrong but I happen to want to carry off your women. You know, you’ve got the most beautiful girls and I’m going to fight you for them. If I had done that, I would be very careful not to kill the girls.”

In modern war we don’t care. The only people who are safe are in the Air Force! They’re way up there, you know, or else they’ve got subterranean caves they’re in— women and children be gone! They can be frizzled with a Hiroshima bomb. But we sit in the plane and be safe. Now this is inhumane because we are fighting ideologically, instead of for practical things like food, and possessions, and being greedy. So that’s why the Confucian would say he trusts human passions more than he trusts human virtues: righteousness, goodness, principles, and all that high-fallutin’ abstractions. Let’s get down to earth, let’s come off it.

So then, this is why the kind of man in whom the kind of nature, the kind of human nature in which trust is put. Because you see, look, if you are like the Christians and the Jews—not so much the Jews, but mostly the Christians—who don’t trust human nature, who say,

“It’s fallen, it’s evil, it’s perverse,” that puts you in a very funny position. Because if you say, “Human nature is not to be trusted,” you can’t even trust the fact that you don’t trust it! See where you’ll end out? You’ll end out in a hopelessness!

Now it’s true, human nature is not always trustworthy, but you must proceed on the gamble that it’s trustworthy most of the time, or even 51% of the time. Because if you don’t, what’s your alternative? You have to have a police state. Everybody has to be watched and controlled, and then who’s going to watch the police? And so, you end up this way, in China just before 250 B.C., there was a short-lived dynasty called the Ching Dynasty that lasted fifteen years. And the man decided who was the emperor of there, that he would rule everybody. Everything would be completely controlled, and his dynasty would last for a thousand years. And it was a mess. So the Hun Dynasty, which lasted from 250 B.C. to 250 A.D. came into being, and the first thing they did was to abolish all laws, except about two. Q. What were those? A. You know, elementary violence… you mustn’t go around killing people and things like that, or robbing, but all the complexity of law. And this Hun Dynasty marked the height of Chinese civilization—the real period of great, great sophistication and peace… China’s Golden Age. I may be over-simplifying it of course, but all historians do. But this, this was a marvelous thing you see. It’s based on this whole idea of

the humanism of the Far East—that although human beings are skalliwags, they are no more so than cats, and dogs, and birds and you must trust human nature. Because if you can’t, you’re apt to starve.

I’ve talked for long enough. What I suggest is, in these seminars that we have a brief intermission so we can stretch for five minutes or so, and then we finish this at 1 o’clock, but you can come back and ask questions in about 5 minutes time.