‘He Keeps Alive With His Colt .45’

by Howard Hughes

In October 1967, a western was released in Italy that had such a huge impact on Italian cinema that it resonated throughout the seventies. God Forgives – I Don’t, a tough, Almeria-shot spaghetti, was directed by Giuseppe Colizzi. Two gunmen, Cat Stevens and Hutch Bessy, team up to track down an outlaw, Bill San Antonio, who has faked his own death, but continues to rob trains. The action sequences were very brutal: the film opens with a driverless train crashing into the buffers at Canyon City station, with everyone on board dead. But there was also fine comic interplay between the two heroes: Cat was an excellent gunman, acrobat, knifeman and fistfighter (The Magnificent Seven rolled into one), while his partner Hutch was a man mountain, with the strength of ten. These two were played by a pair of pseudonymous Italians – Venetian ‘Terence Hill’ and Neapolitan ‘Bud Spencer’. Via the ‘Trinity’ films – They Call Me Trinity (1970) and Trinity is Still My Name (1971) – Hill and Spencer would go on to dominate Italian cinema for the next decade and become the most popular domestic comedy duo of all time. The partnership was formed by chance. When God Forgives – I Don’t was planned, the original lead was Peter Martell, but he broke his leg as the film was about to start. It was going to be called Il Cane, Il Gatto, Il Volpe (‘The Dog, the Cat, the Fox’); with Spencer already cast as the ‘Dog’ and Frank Wolff as the ‘Fox’, the role of the ‘Cat’ was offered to Terence Hill.

Financed by Italo Zingarelli (who had already produced Hate for Hate and directed The Five Man Army), director Enzo Barboni cast Hill and Spencer in his latest project, They Call Me Trinity. Barboni wrote the story and the screenplay. Bambino, a horse-rustler, has escaped from the Penitentiary in Yuma. He’s biding his time, posing as a sheriff in a township where Major Harrison’s men (in league with a bunch of Mexican raiders led by bandit Mescal) are persecuting the pacifist Mormons. The major wants their lush valley as pasture for his horses. Bambino is waiting for his henchmen, Weasel and Timid, to plan their next hold-up. Partly out of decency – and partly to get his hands on the major’s horses – Bambino sides with the Mormons.

Trinity arrives in town and is enlisted by his half-brother to help; Bambino, a sheriff only because he stole the star from a peace officer he ambushed, appoints the unpredictable Trinity as his deputy and nervously awaits the impending chaos. Trinity quickly makes an impression on the major’s men, though Bambino is not impressed by the catalogue of disaster: ‘One store destroyed, three heads split like overripe melons, one man wounded and one castrated…all in two hours! Just two hours I left you alone.’ ‘Well you asked me to give you a hand,’ notes Trinity. Bambino, Trinity, Weasel and Timid teach the Mormons how to use their fists, and in the finale they defeat their enemies in a huge punch-up. The story contains elements of Destry Rides Again (1939), Shane (1953), Rio Bravo (1959) and The Magnificent Seven (1960); Barboni’s original script featured only Trinity, but Zingarelli suggested the addition of pugnacious Bambino, on hand to brain the opposition with his lethal punches.

With the feats of strength and lively scuffles, spaghetti westerns were back in muscleman territory (‘Bambino the Mighty’), but the muscle-bound beefcake is contrasted with a clever, agile sidekick – a character in the mould of Giuliano Gemma’s Krios in Sons of Thunder (1962), one of the few Italian mythical heroes to use acrobatics and guile rather than strength to defeat the villains. Contrasting comedy teams had always been popular in Italy, the most obvious example being tall, urbane Ciccio Ingrassia and short, uncouth Franco Franchi, who made parodies of every popular Cinecitta-genre. Even a comedy team like Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were popular in Italy; Bedazzled, a moderate grosser in most countries, was the third-biggest money-maker in Italy in 1967 and led to their casting in the Italian caper Monte Carlo or Bust (1969).

Previously cast as a lightweight dreamboat, Terence Hill’s real name was Mario Girotti, and his family was of German descent. He started his career as a youngster in fifties Italian productions and made his mark as Count Cavriaghi in Visconti’s The Leopard (1963). He also appeared in one of the best ‘Winnetou’ movies, Last of the Renegades (1964 – also called Winnetou II) as 7th Cavalry Lieutenant Merrill. Hill enjoyed a three-year contract in Germany, but it was his gritty role in God Forgives – I Don’t and his Franco Nero impersonation in Ferdinando Baldi’s Django Get a Coffin Ready (1968) that revealed his star quality. Prior to his role as Django, Hill made Rita of the West (1967), the infamous musical spaghetti. He played Black Stan, the lover of Little Rita, though he tried to blend into the background during the production numbers. For God Forgives – I Don’t, his first Italian western, Girotti was asked to anglicise his name. ‘Terence Hill’ was given to him (he was asked to choose from a list of names); he was not inspired by Latin historical authors (‘Terenzio’) or his wife’s maiden name (Lori Hill), as his publicity often claimed.

‘Bud Spencer’ (real name Carlo Pedersoli) had won a silver swimming medal at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics and subsequently managed to break into acting. Spencer (who named himself after Spencer Tracy) debuted in Quo Vadis? (1951). God Forgives – I Don’t was his first western, though in interviews Spencer maintains that it was he who replaced injured Martell in the film. Following God Forgives, he made three westerns without Hill, Today it’s Me…Tomorrow You (1968), Beyond the Law (1968) and The Five Man Army (1969).

The huge success of God Forgives – I Don’t (it was the number-one film in Italy in 1967) resulted in two sequels, inferior in quality, but big box-office hits: Ace High (1968) and the pedestrian, circus-bound Boot Hill (1969). Ace High (retitled Revenge at El Paso) remains one of the most financially successful spaghettis of all time and teams the duo with a gunman named Cacopoulos (played by Eli Wallach). More boisterous than God Forgives – I Don’t, Ace High features a lighter side to the Hill and Spencer team, with Spencer brawling his way through several knockabout fistfights.

Renowned director of photography Enzo Barboni had shot some of the best spaghetti westerns, working particularly well with Sergio Corbucci on Django; in a cutting-room oversight, Barboni can be seen, camera in hand, during Django’s barroom punch-up. Barboni also had aspirations as a director. While photographing Texas Adios (1966), he approached Franco Nero with a comedy script he was working on, but Nero wasn’t interested in a light-hearted western, so the project was put on hold. Barboni met Hill when he photographed Rita of the West and Django Get a Coffin Ready, and met Spencer while photographing The Five Man Army in 1969. That same year, Barboni adopted the pseudonym ‘E.B. Clucher’ and made his directorial debut with an autumnal western called The Unholy Four (also released as Chuck Mool). Influenced by Corbucci’s early work, it featured an amnesiac gunman (Leonard Mann) escaping from the State Mental Institution to seek revenge on those who wrongly put him there; here the hero is a ‘man with no name’ only because he has forgotten it.

When They Call Me Trinity was first announced, the leads were Peter Martell as Trinity and Luigi Montefiore (who used the pseudonym ‘George Eastman’) as Bambino, but Barboni eventually decided on Hill and Spencer for the roles. Barboni filled out his cast with some familiar faces. Steffen Zacharias (from Ace High and The Five Man Army) played Jonathan Swift, the housekeeper in the sheriff’s office. Dan Sturkie (from The Five Man Army) played the Mormon leader Brother Tobias. Remo Capitani (a stuntman from Colizzi’s westerns and The Unholy Four) played mad Mexican renegade Mescal. Farley Granger played southern horse-obsessed rancher Major Harrison (named Harriman in the Italian print) as an effete version of Major Jackson in Django. Granger was best known as the star of Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951), and for his appearance in Luchino Visconti’s Senso (1954). He had been a regular in Hollywood productions until 1955, when he suddenly retired from the screen to concentrate on TV and theatre work. He resurfaced in the late sixties in Italy, and Major Harrison was one of his first comeback roles. Trinity also features Terence Hill’s 10-month-old son Jess, as the Mormon baby who sits on Trinity’s knee.

They Call Me Trinity was shot in Italy; it was financed by Italian-based West Film. Aldo Giordani was hired as director of photography and Barboni includes several authentic background details – locals tanning cowhides in town, the halfbuilt Mormon settlement and a stage-station shack with a cow grazing on the roof – based on period photographs. The town set was at Incir De Paolis Studios, near Rome (also used in The Five Man Army); the stage station was in the Magliana quarry, Lazio. The beautiful grassy valley locations were shot in the Parco Dei Monti Simbruini, to the east of Rome, where the Mormons’ camp was constructed. The verdant countryside locations give the film a fine edge, a pleasant change from the stark desert. The same lush woodlands, hills and rock outcrops were later seen in ‘Trinity’ derivatives like Panhandle Calibre .38 (1971). The picturesque waterfall where Trinity frolics with Sarah and Judith, two Mormon women, was the Monte Gelato falls in the Treja Valley Park, Lazio; in this scene Trinity claims that he can’t swim, though Hill and Spencer used to swim for the same team in Rome.

The two brothers look nothing like each other and therein lies the comedy. Trinity is a comical western hero – a cross between a lethal gunslinger and a beguiling buffoon. He wears a tatty pair of dungarees, a moth-eaten shirt and a low-slung gunbelt, and travels around on a horse-drawn Indian travois – a sort of bumpy, mobile hammock. He is also extremely unhygienic; when Trinity walks into a cantina and brushes himself off, he is barely visible through the dust cloud. He fears no one (from saddle-tramp bounty-hunters to the fastest professional guns), but the thought of responsibility, hard work and the horror of ‘settling down’ fills him with dread.

His colossal brother Bambino was played by Spencer as a dim-witted bruiser. Theirs is the classic teaming of brains and agility with pigheadedness and brawn, which had already been exploited by Colizzi. Bambino knows what he wants (the major’s herd of stallions) and Trinity knows how to get it (by helping out the Mormons). If dim-witted Bambino gets an idea in his head, it is only because Trinity planted it there. Bambino is an indestructible rock, as the toughest punches and slaps bounce off him. He bears a resemblance to the character of Obelix, the comic-strip Gaul who fell into the magic invincibility potion when he was a baby. Obelix’s favourite move was the uppercut, while Bambino’s speciality is piledriving punches, usually applied to the victim’s forehead, as though he is trying to drive his opponent into the ground like a nail.

Comedy westerns had always been popular. Some of the best examples from Hollywood were James Stewart’s Destry Rides Again (1939), Bob Hope’s The Paleface (1948) and its sequel Son of Paleface (1952) and Cat Ballou (1965 – notable for Lee Marvin’s drunkard Kid Sheleen). All were successful because they respected genre convention – laughing with the characters rather than ridiculing them. There had even been some comedy spaghettis, ranging from the Franchi and Ingrassia series, to farce westerns like I Came, I Saw, I Shot (1968) and The Bang Bang Kid (1967 – featuring a gunslinging robot), though even the most serious Italian westerns had some elements of humour. The first successful comedy spaghettis were Franco Giraldi’s ‘MacGregor’ westerns (Seven Guns for the MacGregors and Seven Women for the MacGregors); and Django Shoots First (1966), which featured bar-room brawls and a lightweight hero played by Dutch actor Roel Bos (under the alias ‘Glenn Saxson’).

The enduring influence on Barboni was Laurel and Hardy’s Way Out West (1937). Here, the established personas of Stan and Ollie were transposed unchanged into the wild west. They arrive in Brushwood Gulch to deliver an inheritance (a locket and the deeds to a gold mine) to the daughter of their deceased partner, but wily saloon-owner Mickey Finn (played by James Finleyson) tricks them out of it. What makes the film so successful are Stan and Ollie’s comedy antics and their musical numbers. On a stagecoach Ollie attempts to strike up conversation with a female passenger: ‘A lot of weather we’ve been having lately’. When they arrive in town, a bunch of singing cowpokes (billed as the Avalon Boys) are airing a gentle toe-tapper called ‘At the Ball, That’s All’ on the porch of Mickey Finn’s Palace, and Stan and Ollie do a soft-shoe shuffle on their way into the saloon. Later they perform their best-known song, ‘Trail of the Lonesome Pine’, while propping up the bar. When the deed is stolen, Stan swears that if they don’t get it back, he will eat his hat, but their first attempt fails and Ollie makes him keep his word. ‘Now you’re taking me illiterally,’ comments Stan. But it is the ahead-of-their-time sight gags that made the film so influential. Stan’s thumb-lighting, Ollie’s neck-stretching, several wacky chases and their aborted attempt at acrobatics involving Ollie, a block and tackle, a mule and a high window.

They Call Me Trinity begins with a sequence based on its equivalent in Way Out West. Stan and Ollie make their way towards Brushwood Gulch – with Stan leading the way and Ollie lying on their mule-drawn travois. As they mosey along, the litter gives Ollie a rough ride, first over bumpy rocks in the road and then through a river. In the next sequence Ollie is wrapped in a blanket and there’s a washing line strung across the travois, drying his clothes. In Barboni’s title sequence, as yawning Trinity is dragged along on his litter by a horse with a good sense of direction, the horse drags him through a river, submerging its passenger. The difference is that Trinity is so laid-back he doesn’t ‘bat an eye’.

Barboni deployed a parade of western stereotypes (both American and Italian) for his way-out west. Neat and tidy Jonathan Swift – Bambino’s put-upon housekeeper in the sheriff’s office – is a fastidious version of Walter Brennan’s Stumpy in Rio Bravo. In fact, the early section of Trinity strongly resembles a parody of Howard Hawks’s film, with Bambino as Sheriff John T. Chance and Trinity as his young deputy, Dude. Trinity even features the sheriff’s ‘nightly scolding’ of the rough elements in the town saloon. As Bambino makes his way to the saloon, a local cheerfully offers, ‘Evenin’ sheriff’, to which he curtly replies ‘Shut up’. Zacharias’s parodic performance as Jonathan enhances such references. He does Bambino’s washing and cooking, and is a stickler for cleanliness, refusing to shake Trinity’s filthy hand (‘Don’t want to catch no tetanus’). Zacharias delivers the best lines, provided by Gene Luotto’s English translation of Barboni’s original script. At one point Jonathan points out that Bambino always seems to be elsewhere when trouble starts – ‘I’ve never met such an unlucky sheriff’.

The major hates the Mormons, and Farley Granger’s drawling accent works best when he vents his rage on the farmers. In one scene he tells how, through their faith, they settled in the valley to live in ‘dignified poverty’. ‘Then good old faith forms a community,’ fumes Harrison, ‘builds a house that could shelter an army and fills the corrals with livestock.’ The major hires Jack and Mortimer, two humourless hired guns (played by Alessandro Sperli and Dominic Barto) to tackle the ‘fast deputy’. But Trinity is easily a match for them, humiliating the duo by making them run out of town in their long johns.

Mescal is the ultimate send-up of Corbucci’s comical Mexican generals, with his sombrero, cannon-like pistol, bandoleers and an epaulette hanging around his neck. When he raids the Mormon settlement he is offered their meagre food, but demands ‘good soup with garlic and mucho vino’ for their next visit. Later, when the Major hires him to get rid of the Mormons, he is paid with 20 stallions, but Mescal would prefer it if he could steal the horses; for bandits to work for pay is too embarrassing.

The noble Mormons, led by their stalwart leader Brother Tobias, are righteous, God-fearing people. As Jonathan says, ‘All they do is pray and work, work and pray’. When Trinity and Bambino first arrive at the camp, Tobias shouts, ‘Welcome brothers!’ and Bambino frowns, ‘Hey, who told him we were brothers?’ Tobias speaks in quotes from the Bible; Trinity falls for Sarah and Judith (two Mormon women he has saved from the major’s men); and Tobias describes their rescue thus: ‘They were innocent doves surrounded by evil and the Lord heard their prayers and sent you to answer’. Bambino shrugs, ‘It was approximately like that’. It is Tobias’s own interpretation of the Bible that helps the Mormons win the day. In the finale, the major’s gang attack the Mormon camp. In a variation on The Magnificent Seven, the farmers have no firearms, but have been trained in fisticuffs by Trinity, Bambino and Bambino’s two bumbling cohorts, Timid and Weasel. They dupe the major into ordering his gang to take off their guns (out of respect for the Mormons’ non-violent beliefs), then Tobias reads from the Bible: ‘In the words of Coeleth, son of David, King of Jerusalem, “There’s a time to fight and a time to win!”’ which is the Mormons’ cue to confront their oppressors.

Barboni’s forte is the well-choreographed, action-packed fistfights, with much breakaway furniture and hidden crash mats. In that respect, Trinity’s huge stunt crew were the stars of the show. Hill and Spencer performed all their own stunts and fights, while most of the male cast-members were stuntmen, including Osiride Pevarello, Alberto Dell’Aqua and Lorenzo Fineschi (as Mormons) and Riccardo Pizzuti, Gaetano Imbro and Paolo Magalotti (with the major). The punch-ups were choreographed by Giorgio Ubaldi. In the fight between Trinity and two of the major’s henchmen in a general store (a parody of the Grafton Store scene in Shane), Trinity bangs one man’s head against a cash register, which rings up ‘Thank You’. In a saloon fracas, Trinity and Bambino face a bunch of the major’s men, but Trinity, having started the argument, sits back and watches his brother pummel the gang.

Trinity owes much to cartoons, especially Trinity’s speeded-up gunslinging prowess and ridiculously accurate marksmanship. In one sequence, he draws and reholsters his Colt Navy three times before his opponents can twitch. At the chaparral cantina, Trinity devours a huge pan of beans, mopped up with bread and washed down with tequila, then belches loudly. Two bounty-hunters in the cantina check their collection of reward posters and ask his name. ‘They call me Trinity,’ Hill answers, as the gunmen’s jaws drop open. ‘The Right Hand of the Devil!’ says one, the other adding ‘They say you’ve got the fastest gun around’. ‘Is that what they say?’ grins Trinity, ‘Gees.’ As he walks to his travois they aim to shoot him in the back, but without turning around Trinity draws his pistol and kills them both.

Barboni integrates running gags into his films, and They Call Me Trinity has two good examples. Trinity arrives in town with a wounded Mexican prisoner (Michele Cimarosa). In an unsanitary operation, Trinity gets the Mexican drunk, Bambino removes the bullet with a red-hot knife and Trinity plugs up the hole with his finger. The anaesthetic proves so popular that the Mexican refuses to budge from the jail for the duration of the film. Another running gag recounts the story of the sheriff (Ugo Sasso) from whom Bambino stole the badge. The sheriff wasn’t following Bambino – they just happened to be going the same way – but Bambino ambushed the lawman and stole his star, leaving him for dead. Subsequently, it appears the lawman, now lame in one leg, survived. ‘Sheriff’ Bambino receives a note from the injured lawman: ‘Now he wants me to give him a hand to find me’. Later Timid and Weasel encounter the same sheriff, and Bambino asks if they finished him off: ‘Well almost… Timid got him in the good leg, then we broke his crutches.’ Jonathan describes the lawman thus: ‘Moustache, star on his chest, crutches – a typical crippled sheriff’ – a joke at the expense of Hawks’s Rio Bravo sequel, El Dorado (1967) which saw John Wayne and Robert Mitchum hobbling down the street on crutches.

Barboni handles Trinity’s fade-out particularly well. With the major defeated, he rides off to Nebraska, in search of pastures new, while Bambino discovers that Trinity has allowed the Mormons to claim the major’s horse herd by branding them with a ‘Ten Commandments’ motif. Furious, Bambino leaves and Trinity stays on to begin a new life. As Tobias welcomes the ‘lost sheep’ into the fold, Trinity hears the dreaded words ‘labour’, ‘hard day’s work’ and ‘fatigue’, and decides to follow Bambino’s dust towards California.

The music to They Call Me Trinity was written by Franco Micalizzi, who had previously worked with Roberto Pregadio on his famous whistled western score for The Forgotten Pistolero (1970). Trinity’s jokey title-sequence travois ride is scored with a light-hearted, catchy theme song, which establishes the mood. The opening shot of Trinity’s holstered pistol, dragging through the dust, is accompanied by the sound of a rattlesnake. Then a lazy whistler, an oboe, honky-tonk piano and acoustic guitar begin an idle melody. David King belts out the parodic title song in classic cowboy style:

You may think he’s a sleepy-type guy, always takes his time

Soon I know you’ll be changing your mind, when you’ve seen him use a gun boy

He’s the top of the west, always cool he’s the best

He keeps alive with his Colt .45

Who’s the guy who’s a riding to town, in the prairie sun

You won’t bother to fool him around, when you’ve seen him use a gun boy When you’ve seen him use his gun.

The piece was written by Franco Micalizzi and Lally Stott. Englishman Stott was brought in to write the English lyrics and also had a hand in the melody; he is billed on the instrumental versions of the theme too. Stott later had a hit in the early seventies with a cover of ‘Chirpy Chirpy, Cheep Cheep’. With Alessandroni’s whistling, his singers harmonising with lyrics (‘Don’t! Don’t!’) and big-band brass and drum-kit, King delivers the song with just the right amount of half-hearted Dean Martin-esque conviction to make it a success. King is billed as ‘Annibale’ on the Italian soundtrack releases.

Throughout the film a whistled version of the theme accompanies Trinity as he ambles towards his next run-in with the major, while an up-tempo version, with electric piano and ‘wah-wah’ guitar, scores the brothers’ ride to the Mormon camp. The Mormons have a sombre hymnal piece, used as the background score to the climactic fistfight. The major has a trumpet riding theme (with horn, electric guitar and trumpet flourish) and Mescal’s bandits have Micalizzi’s take on the ‘Mexican Hat Dance’. In the waterfall sequence, in which Trinity splashes about with Sarah and Judith, a ‘love theme’ incorporates mellow guitar, strings and a synthesised panpipe. For the scene in which two black-clad hired guns walk menacingly down the main street, Micalizzi composed an effective pastiche – a slow bolero with familiar Don Giovanni strings, electric guitar, rattlesnake maracas and mariachi trumpet.

When They Call Me Trinity was released in Italy, just before Christmas 1970, Barboni had a smash hit. In Germany the film was retitled Die Rechte und Linke Hand Des Teufels (‘The Right and Left Hand of the Devil’, in reference to the two heroes), while Trinity was christened Müde Joe (Tired Joe) and Bambino Der Kleine (the little one). In Spain it outgrossed every previous Italian western except For a Few Dollars More. Hill and Spencer were already established as a partnership from their Colizzi films, and the film was also lucrative when it had its UK and US release in 1971. It was distributed by Joseph E. Levine’s Avco Embassy Pictures, uncut at 106 minutes, and garnered a ‘G’ rating (all ages permitted). US publicity for the film included the taglines: ‘He was on the side of law and order…he was on the side of crime and chaos…he was on any side that would have him!’ and ‘He was so mean, he shot his horse for smiling’, which sat oddly with Hill’s persona; if there is one thing Trinity loves, it is his rheumy-eyed horse. Gene Luotto oversaw the dubbing of the English-language print, and the result was way above average for a foreign western. This was aided by Hill, Spencer, Zacharias and the other main actors speaking their lines in English. Even so, critics were divided: some found the film ‘good fun’, while others considered it uneven and wondered how Hill and Spencer ‘earned a crust as actors’.

Trinity’s success opened the saloon doors for the unruly mob of comedy spaghettis that followed. Some incorporated the cartoonish fights into kung-fu westerns like The Fighting Fists of Shanghai Joe (1973) and Blood Money (1974). The most blatant spin-offs included Franchi and Ingrassia’s Two Sons of Trinity (1972), the ‘Carambola’ series (starring Hill and Spencer lookalikes Michael Coby and Paul Smith) and Jesse & Lester: Two Brothers in a Place Called Trinity (1972), with two brothers (a womanising gunslinger and an honest Mormon) arguing over an inheritance. Moreover, many westerns appeared in the early seventies with They Call Me… in the title, including Holy Ghost (1970), Cemetery and Hallelujah (both 1971), Veritas, Providence and Amen (all 1972).

The true heir to They Call Me Trinity is Barboni’s own sequel with Hill and Spencer, Trinity is Still My Name (1971), which sees Trinity and Bambino trying unsuccessfully to become outlaws, while being mistaken for federal agents on a special mission. It is more fragmented than its predecessor, with a series of improvisory set pieces becoming more like a revue. The action includes gunrunning monks, farting babies, comic card games, Trinity and Bambino’s appalling table manners in a fancy French eating house and a grandstand finale that descends into a riotous game of American football. This irreverent humour reappeared to great success in Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles (1974), which was retitled in Italy Mezzogiorno e Mezzo di Fuoco (‘Noon and a Half of Fire’), in reference to High Noon (which was retitled Mezzogiorno di Fuoco).

The ‘Trinity’ films are often accused of being childish, meathead entertainment, but Hill and Spencer continued to be hugely popular with young and old audiences throughout the seventies. Among their biggest hits were All the Way Boys! (1972) and Watch Out, We’re Mad! (1973); between 1971 and 1994 they made 12 films together. Their films were never graphically violent, making them suitable for the whole family. This was for obvious financial reasons: the lower the certificate, the wider the range of audience able to see the film.

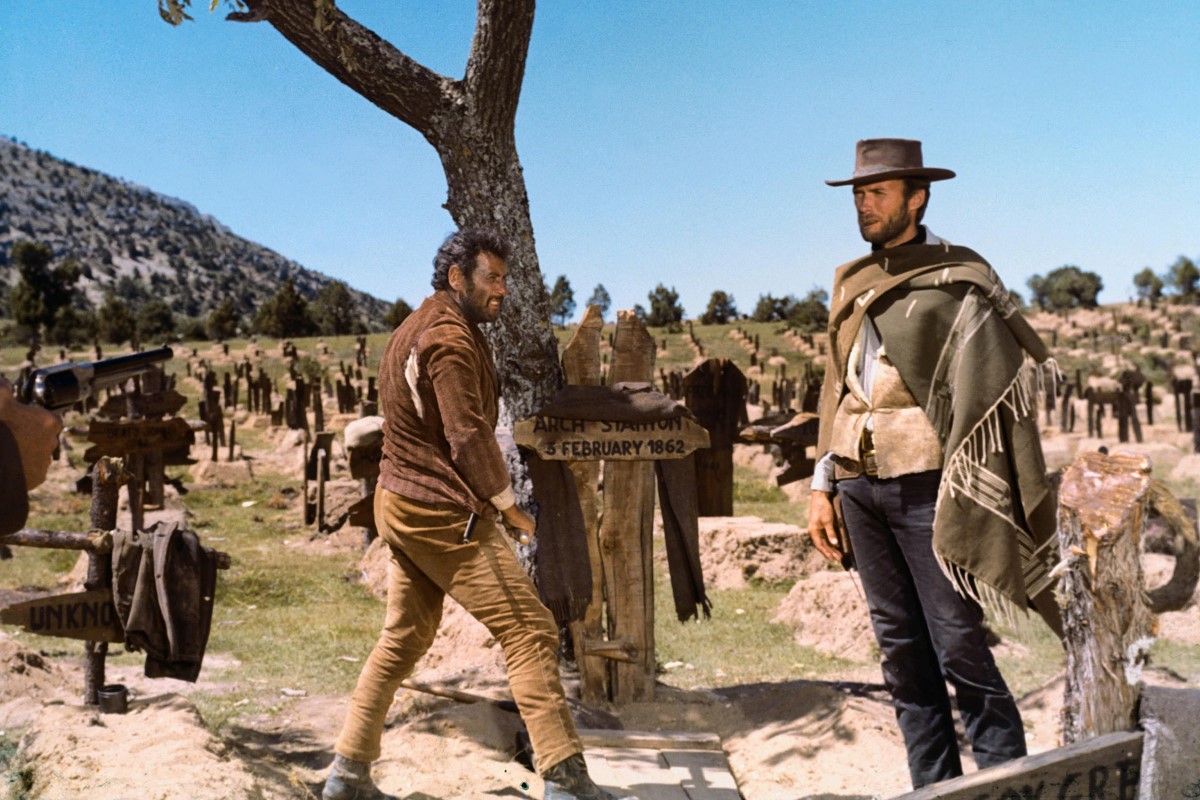

They Call Me Trinity is the twenty-second most successful Italian film of all time – one place behind The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, though their reputations outside Europe are completely different. While The Good is praised as one of the greatest westerns of all time, the ‘Trinity’ films are still treated with critical disdain. Barboni had the last laugh when Trinity is Still My Name outgrossed all western opposition in Italy, including Leone’s most successful western, For a Few Dollars More; it remains the fifth most financially successful Italian film of all time.

They Call Me Trinity is Hill and Spencer’s finest vehicle; the duo were underrated by critics as actors, but equally the directors they worked with were all-important. They followed They Call Me Trinity with the swashbuckling The Black Pirate (1971), directed by ‘Vincent Thomas’ (Lorenzo Gicca Palli), which sank like a stock-footage galleon. Hill played a thinly disguised Trinity in two more westerns – My Name is Nobody (1973) and Nobody’s the Greatest (1975) – while Spencer’s performance as Coburn in The Big and the Bad (1971) owed much to Bambino. But when they were together, and especially in They Call Me Trinity, they were like their screen personas – invincible.

* * *

They Call Me Trinity (1970)

original title: Lo Chiamavano Trinità

Credits

DIRECTOR – ‘E.B. Clucher’ (Enzo Barboni)

PRODUCER – Italo Zingarelli

STORY AND SCREENPLAY – ‘E.B. Clucher’ (Enzo Barboni)

COSTUMES – Enzo Bulgarelli

EDITOR – Gianpiero Giunti

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY – Aldo Giordani

MUSIC COMPOSER – Franco Micalizzi

MUSIC CONDUCTOR – Gianfranco Plenzio

Interiors filmed at Incir De Paolis Studios, Rome

Techniscope/Technochrome

An Italian Production for West Film (Rome)

Released internationally by Avco Embassy Pictures

Cast

‘Terence Hill’, Mario Girotti (Trinity); ‘Bud Spencer’, Carlo Pedersoli (Bambino); Steffen Zacharias (Jonathan Swift); Dan Sturkie (Brother Tobias); Gisela Hahn (Sarah); Elena Pedemonte (Judith); Farley Granger (Major Harrison); Ezio Marano (Weasel); Luciano Rossi (Timid); Remo Capitani (Mescal); Riccardo Pizzuti (Jeff); Paolo Magalotti (Major Harrison’s lieutenant); Ugo Sasso (real Sheriff); Osiride Pevarello (Joe, Mormon in general store); Gigi Bonos (Mexican innkeeper); Michele Cimarosa (drunken Mexican prisoner); Dominic Barto (Mortimer); Alessandro Sperli (Jack); Tony Norton (bounty-hunter); Fortunato Arena (general storekeeper); Jess Hill (Mormon baby); Gaetano Imbro (bearded member of Harrison’s gang); Alberto Dell’Aqua (young blond Mormon); Herman Reynoso (Mormon ‘Brother Lookout’); Lorenzo Fineschi (blond Mormon); with Vito Gagliardi, Antonio Monselesan and Franco Marletta

Source: Howard Hughes, Once Upon a Time in the Italian West, I. B. Tauris, 2006