Pauline Kael had a mixed response to Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories (1980). In her review, she acknowledged the film’s technical and visual achievements but expressed reservations about its overall impact and narrative structure.

While she appreciated the film’s visual style, including its use of black-and-white cinematography, Kael found fault with what she perceived as an uneven mix of humor and seriousness. She felt that the film lacked the coherence and emotional resonance that she found in some of Allen’s earlier works.

* * *

In her review of Woody Allen’s “Stardust Memories” (1980), Pauline Kael stated that the film felt like watching a loop with the same thoughts repeated over and over. She found the material fractured and the scenes very short, and there was not a single one that she was sorry to see end.

Kael also mentioned that “Stardust Memories” doesn’t seem like a movie, or even like a filmed essay; it’s nothing. She criticized the film for degrading the people who respond to Allen’s work and presenting himself as their victim.

Despite her friendship with Woody Allen, her criticism of “Stardust Memories” was so severe that it reportedly ended their friendship.

* * *

Pauline Kael was not a fan of Stardust Memories, calling it “a horrible betrayal” of Allen’s fan base and “a whiny case of the celebrity blues.” She found the film to be self-indulgent and unfunny, and she accused Allen of playing a character who is simply not likable.

Kael was particularly critical of Allen’s portrayal of Sandy Bates, the film’s main character. She found Bates to be a shallow and narcissistic man who is constantly complaining about his fame and fortune. She also found the film’s ending to be unsatisfying, arguing that it does not offer any resolution to Bates’s problems.

Overall, Kael’s review of Stardust Memories is a negative one. She found the film to be unfunny, self-indulgent, and poorly made. She also criticized Allen’s performance in the film, calling his character shallow and narcissistic.

by Pauline Kael

At the beginning of Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories, there is a Bergmanesque nightmare sequence, silent except for the sound of ticking. Woody Allen is on a stalled train, and as he looks around he sees big-nosed misery on the other faces; his fellow-passengers are self-conscious grotesques who might have been photographed by Diane Arbus. Peering out the window, he can see that on the next track there’s another stalled train that is headed in the same direction, and it’s full of swinging, beautiful people living it up and having a ball.

He motions to the conductor that he’s on the wrong train and tries to get out, but he’s sealed in. This visual metaphor has almost the same meaning as the Groucho epigram that was quoted twice in Annie Hall: “I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would have me for a member.” The clubs from which Groucho was excluded were, of course, the gentiles’ clubs, and he was expressing his chagrin at being lumped with the other Jews! (Excluded from a California beach club, Groucho wrote the organization, “Since my daughter is only half Jewish, could she go in the water up to her waist?”) Stardust Memories might be described as an obsessional pastiche. It is modelled on Fellini’s 8½, and the bleached-out black-and-white cinematography suggests a dupe of a dupe of 8½, with some allusions to the clown’s pasty despair at the start of Bergman’s The Naked Night. The theme recalls Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels, which is about an acclaimed director who doesn’t want to go on making popular comedies—he wants to be stark, tragic, and realistic.

Woody Allen calls himself Sandy Bates this time, but there’s only the merest wisp of a pretext that he is playing a character; this is the most undisguised of his dodgy mock-autobiographical fantasies. The setting is the Hotel Stardust, a resort on the New Jersey seashore, where a woman film critic (played by Helen Hanft) conducts weekend seminars; for a fee, the guests spend a weekend looking at the work of a filmmaker and discussing it with him—and they also get to press his flesh. This weekend, Sandy Bates is the celebrity-in-residence; he runs his new picture as well as clips from his comedies, and the discussions are intercut with flashbacks, hallucinations, and fragmentary encounters. The actors slip in and out of the films and his life. Feeling besieged, he goes through a vague son of crisis, possibly brought on by the seminar guests. Each of them wants something from him—he is asked to appear at a benefit for cancer, to give some personal article to an auction, to sign a petition, to read a script, to answer an imbecilic question. And these pushy fans who treat him in such an overfamiliar way are gross or big-nosed and have funny Jewish names. They’re turned into their noses; they leer into the lens, shoving their snouts at Sandy Bates. They chide him (indulgently) for his recent seriousness, and he complains, “I don’t want to make funny movies anymore. They can’t force me to. I look around the world and all I see is human suffering.”

In Stardust Memories, Woody Allen degrades the people who respond to his work and presents himself as their victim. He seems to feel that they want him to heal them; the film suggests a Miss Lonelyhearts written without irony. (Maybe Sandy Bates means he sees human suffering when he looks around his apartment: his walls are decorated with blowups of news photographs, such as the famous one of the execution in a Saigon street during the Tet offensive, and they change like mood music. Is this evidence of Sandy Bates’s morbidity, or is it how he proves that he’s politically and socially with it? Is there any way it can’t be a joke? What is going on in this movie?) Woody Allen has often been cruel to himself in physical terms—making himself look smaller, scrawnier, ugly. Now he’s doing it to his fans. People who, viewed differently, might look striking or mysterious have their features distorted by the camera lens and by Felliniesque makeup; they become fat-lipped freaks wearing outsize thick goggles. (They could serve as illustrations for the old saw that Jews are like other people, only more so.) People whose attitudes, viewed differently, might seem friendly or, at worst, overenthusiastic and excited are turned into morons. Throughout Stardust Memories, Sandy is superior to all those who talk about his work; if they like his comedies, it’s for freakish reasons, and he shows them up as poseurs and phonies, and if they don’t like his serious work, it’s because they’re too stupid to understand it. He anticipates almost anything that you might say about Stardust Memories and ridicules you for it. Finally, you may feel you’re being told that you have no right to any reaction to Woody Allen’s movies. He is not just the victim here, he’s the torturer. (A friend of mine called the picture Sullivan’s Travels Meets the P.L.O.)

The hostility of the standup comic toward his night-club audience is often considered self-evident, but the hostility of a movie director toward the public that idolizes him doesn’t have the same logic behind it, and it’s almost unheard of. Woody Allen has somehow combined the two, and his hostility takes a special form. He’s trying to stake out his claim to be an artist like Fellini or Bergman—to be accepted in the serious, gentile artists’ club. And he sees his public as Jews trying to shove him back down in the Jewish clowns’ club. Great artists’ admirers are supposed to keep their distance. His admirers feel they know him and can approach him; they feel he belongs to them— and he sees them as his murderers.

Conceivably, a comedy could be made about an artist who thinks that those who like his work are grotesque and those who don’t are stupid. This misanthrope would have to be the butt of the comedy, though; his pain would have to be funny—like the pain that Portnoy felt about his life’s being a Jewish joke. But Woody Allen doesn’t show the ability to step back from himself (as he did when he was making comedies); even the notion of doing this particular film in black-and-white is tied up with his not being able to step back. He sees himself only from the inside, and he asks us to suffer for the pain he feels about his success. At times, he sets up scenes as if he recognized that this pain is absurd, but he can’t achieve—or doesn’t want to achieve—the objective tone that would make us laugh. He brings in characters who seem designed for a payoff—an old school chum who complains that he isn’t rich and famous like Sandy, an actress who once played Sandy’s mother in a film and has now undergone cosmetic surgery and thinks she has become a beauty—but he stages their scenes in what appears to be a deliberately off-key, quavering tone, so that everything turns uncomfortable, morose, icky. And whether it’s because of Woody Allen’s desire to show us his loss of faith in these gags, or because of the cinematographer Gordon Willis’s penchant for dark abstractions, they are shot at such a distance that the purpose of the scenes becomes opaque. (The actress-mother is seen in distant, cruel silhouette.)

The film has a single moment of comic rapport: Sandy visits his tough, lively married sister (played by Anne DeSalvo), and they take relish in a shared bitchy laugh about their mother. Yet even this visit begins with an aggressively rancid scene making fun of the sister’s loud, uncouth friends—particularly a fat woman who was raped the night before; inexplicably, she wears a T-shirt with the word “Sexy” across her huge bosom. And the purpose of the visit seems to be to burlesque Sandy’s relatives. The furnishings of the sister’s apartment and the corpulent idiocy of her husband, stuffing his face while pumping on an Exercycle, shriek of bad taste. (The writhing wallpaper in her bedroom suggests something dreamed up for a decorator’s Halloween party.) The only concession to vitality in the movie (besides the sister) is in the great jazz recordings used as the score, though in this atmosphere the music sounds like Fellini Dixieland.

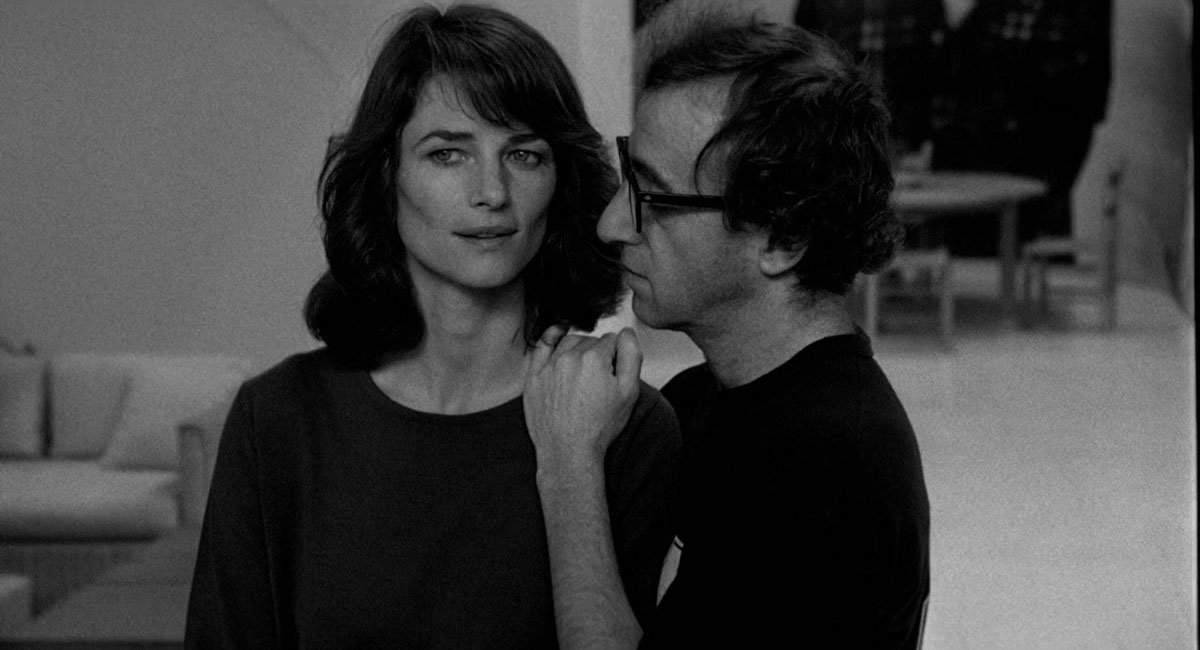

Starting with the two trains, there are a number of potentially funny situations, but they don’t come out funny. You’re not sure how to react: the gags are strained—they seem poisoned by the director’s self-pity. You can’t laugh at the nightmarish melancholy of those dark, pimply train passengers, or at the ugliness of the seminar guests and the sister’s pals. And though Woody Allen’s attitudes may have a lot in common with those of Diane Arbus, you can’t respond as you would to her photographs. The deep malignity in her work gives those photographs an undeniable punch. Woody Allen assembles people and makes them grotesque, but he uses them in such a casual way that he trivializes the ugliness he puts in front of us. There’s no power in the images; he. trivializes even his own malignity by his half-joking manner. And he doesn’t appear to see any comedy in the fact that the only undemanding, unpushy characters in the movie—the three women in Sandy’s life—are all gentile. These women are also indifferent to his work; at least, they don’t offer opinions of it. They don’t have enough independent existence for us to be sure what they’re supposed to represent, and what attracts them to him—if not his films and his fame—isn’t made apparent. But we can see what attracts him to them: they’re the only women on the landscape in “quiet good taste,” the only ones with hair that doesn’t look like plaster of Paris or frizzed wire. Charlotte Rampling, who is posed in closeup after closeup—a ship’s figurehead, like Anouk Aimee in 8½—suggests a decaying goddess. She seems to be used just for her physiognomy—for her bony chest and wide mouth (its corners run right into her cheekbones). Marie-Christine Barrault is used for her matronly-milkmaid-goddess look and the beautiful big teeth that can turn threatening. Jessica Harper is used for her wide brow and perverse, waifish grin. The first two are like toys that Sandy Bates has lost interest in; Harper is a possibility glimpsed which he doesn’t care enough about to pursue.

The Jewish self-hatred that spills out in this movie could be a great subject, but all it does is spill out. The ostensible subject is the beleaguered artist and what the public demands of him. In a Newsweek cover story in 1978, Woody Allen was quoted: “When you do comedy you’re not sitting at the grown-ups’ table, you’re sitting at the children’s table.” From the tone of this film, you would think that vulgarians were putting guns to Woody Allen’s head and forcing him to make comedies. Considering the many respectful, indeed laudatory reviews he got for Interiors, which, he says, even “turned a little profit,” and considering the astonishing success of Manhattan, in which he tried to be both Ingmar Bergman and Charlie Chaplin—a wet mixture if ever there was one—his contempt for the public seems somewhat precipitate.

Woody Allen, who used to play a walking inferiority complex, made the whole country more aware of the feelings of those who knew they could never match the images of Wasp perfection that saturated their lives. He played the brainy, insecure little guy, the urban misfit who quaked at the thought of a fight, because physically he could never measure up to the big strong silent men of the myths—the gentile beefcake. Big strong men know that they can’t live up to the myths, either. Allen, by bringing his neurotic terror of just about everything out front, seemed to speak for them, too. In the forties and fifties, when Bob Hope played coward heroes the cowardice didn’t have any political or sexual resonance, but in the late sixties and the seventies, when Woody Allen displayed his panic he seemed to incarnate the whole antimacho mood of the time. In the sloppy, hairy counterculture era, Americans no longer tried to conform to a look that only a minority of them could ever hope to approximate. Woody Allen helped to make people feel more relaxed about how they looked and how they really felt about using their fists, and about their sexual terrors and everything else that made them anxious. He became a new national hero. College kids looked up to him and wanted to be like him.

That’s why it seems such a horrible betrayal when he demonstrates that despite his fame he still hates the way he looks, and that he wanted to be one of them—the stuffy macho Wasps—all along. There were moments of betrayal in his other films, such as the peculiar jokiness of his using actors smaller than he as his romantic rivals (the Hollywood doper played by Paul Simon in Annie Hall, and Jeremiah, played by Wallace Shawn, in Manhattan). But people in the audience could blot out the puzzling scenes of Annie Hall and Manhattan. In Stardust Memories—awful title!—he throws so much at you that you can’t blink it away. If Woody Allen were angry with himself for still harboring childish macho dreams, that would be understandable, but he’s angry with the public, with us—as if we were forcing him to embody the Jewish joke, the loser, the deprived outsider forever. Comedy doesn’t belong at the children’s table, but whining does.

One of the distinctions that is generally made between a “commercial” artist and a “pure” one is that the former is obsessed with how the audience will react, while the latter doesn’t worry about the audience but tries to work things out to satisfy his inner voice. That Woody Allen should try to become a “pure” artist by commenting on his audience seems a sign that he’s playing genius. In Manhattan, he reworked too much of Annie Hall; it was clear that he needed an infusion of new material. In Stardust Memories, we get more of the same thoughts over and over—it’s like watching a loop. The material is fractured and the scenes are very short, but there was not a single one that I was sorry to see end. Stardust Memories doesn’t seem like a movie, or even like a filmed essay; it’s nothing. You see right through it to the man who has lost the desire to play a character: he has become the man on the couch. He thinks he has penetrated to the core of what life is, and it’s all rotten. No doubt he feels that this is the lousy truth; actually, it’s just the lousy truth of how he feels. But we’ve all felt like that at times; he hasn’t discovered anything that needs to be shared with the world.

In Manhattan, Woody Allen began to use his own face more naturally than he had before on the screen; he didn’t turn into a caricature anymore—it was a naked face, sometimes too naked. He is even more relaxed in Stardust Memories, and in the absence of other characters you may get fed up with his nakedness and, as his depression enters into you, begin to think about what’s in his head. I referred to Woody Allen’s recent films as dodgy because I don’t think anybody knows how we’re supposed to react to the protagonist’s metaphysical head cold—his carrying on about death and the shallowness of his friends. He keeps shifting: at one point in a movie he seems to be its moral center, at another point he’s a sniper who turns petty grievances into moral issues, and at other times he’s the frailest, weakest person around, trying to manipulate people in terms of his needs. In Annie Hall, in Manhattan, and now in Stardust Memories, the protagonist’s high moral tone is often out of scale with what he’s indignant about and he just sounds like a crank, but we can’t tell when Woody Allen means him to sound like one and when Woody’ Allen really is one.

No movie star (not even Mel Brooks) can ever have been more explicit on the screen about his Jewishness than Woody Allen, and he was especially so in his Academy Award-winning romantic comedy, Annie Hall—the neurotic’s version of Abie’s Irish Rose and the TV series “Bridget Loves Bernie.” The herd, Alvy Singer, announced that he was paranoid about being Jewish, and at dinner with Annie’s Midwestern Wasp family he had a flash and saw himself through their eyes as a Hassidic rabbi—not just the outsider but the weirdly funny outsider, too ridiculous to be threatening. What’s apparent in all his movies is that for him Jewishness means his own kind of schlumpiness, awkwardness, hesitancy. For Woody Allen, being Jewish is like being a fish on a hook; in Annie Hall he twists and squirms. And when Alvy sits at that dull Wasp dinner and the screen divides and he sees his own family at dinner, quarrelling and shouting hysterically, the Jews are too heavily overdone for comedy. Here, as almost everywhere else in Woody Allen’s films, Jews have no dignity. That’s just about how he defines them and why he’s humiliated by them.

There was self-love as well as self-hatred involved in Annie Hall, however: Alvy was very quick to decide that almost everyone connected with show business (except for him) was a sellout. Though the story, which turned into a conflict between East Coast and West Coast, faded before it worked itself out, that fading became part of the meaning: relationships fail, and we’re not quite sure why. Diane Keaton’s Annie was full of thoughts that wilted as she tried to express them, and her lyrical, apologetic kookiness gave the film softness, elusiveness. She was fluttery and unsure about everything, yet she went her own way, leaving Alvy to continue his love affair with death—an affair that he seemed to think represented integrity and high seriousness. What made the movie run down and dribble away was that while Woody Allen showed us what a guilt-ridden, self-absorbed killjoy Alvy Singer was, always judging everyone, he (and not just Alvy) seemed bewildered that Annie wearied of Alvy’s obsessions and preferred to move on and maybe even have some fun. By the end, Alvy and the story had disappeared; there was nothing left but Woody Allen’s sadness.

At the opening of Manhattan, Woody Allen’s Isaac Davis spoke about the corruption of the city’s inhabitants in what came across as a satirical commentary; the audience howled. Then that commentary turned out to be the point of view of the picture. But the audience was right to howl: Allen based his case for general moral decay on the weaknesses (not even cruelties) of two or three selfish, confused people. You could indict Paradise on charges like that. In Annie Hall, he gave us an L.A. full of decadent pleasure lovers, and his Manhattan was also full of naughty, self-centered types: he contrasted their lack of faith with the trusting, understanding heart of a loyal child— played by Mariel Hemingway. (What man in his forties but Woody Allen could pass off a predilection for teen-agers as a quest for true values?) It was clear that he thought we all ran around being rotten and chic, and had to come to terms with our shallowness in order to be saved. (At least he gave us a big child to lead us.) Woody Allen the moralist has restated his imponderable questions about man’s destiny so often that in Stardust Memories even he sounds tired of them; he tosses them out unemotionally—it’s his ascetic reflex. He may be ready to become a Catholic convert. If Woody Allen finds success very upsetting and wishes the public would go away, this picture should help him stop worrying.

New Yorker, October 27, 1980

2 thoughts on “Stardust Memories (1980) | Review by Pauline Kael”

What about adding A Passage To India & Empire Of The Sun?

Hi, can you please upload Pauline Kael’s review of HANNAH AND HER SISTERS? Thanks.