by Jonathan Romney

The best place to enter a labyrinth is through its exit. So let’s start with the famous final shot of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), the ill-fated winter caretaker of the Overlook Hotel, sits statuefied in the snow, having met his frozen fate at the heart of the Overlook’s maze, while his wife Wendy and son Danny (Shelley Duvall and Danny Lloyd) are long gone in the snowmobile. The Overlook is quite empty now, apart from its resident phantoms and, in case we’ve forgotten, the corpse of chef Hallorann (Scatman Crothers), the only person Jack has succeeded in killing during his Big Bad Wolf rampage (but then, that’s for the management to worry about when the hotel re-opens the following spring – and, presumably, for the next caretaker to worry about too).

So, amid the quiet – broken only by ghostly strains of a 20s dance tune – the camera tracks slowly towards a wall of photographs from the Overlook’s illustrious history. It closes in on the central picture, showing a group of revellers smiling at the camera, and then, in two dissolves, reveals first the person at the centre of the group – Jack himself, smiling and youthful in evening dress – and then the inscription, “Overlook Hotel, July 4th Ball, 1921”. Cue credits, cue shudder from audience.

Just what makes this chilly payoff so uncanny? It appears to reveal something, the final narrative turn of the screw, or perhaps an explanation of the story’s ambiguities – but really it reveals nothing for certain. What’s more, the last thing we see is not an image but an inscription-hardly the chilling coup de théâtre we expect from a horror film. But The Shining is a film that, while it uses written language sparingly, is very much concerned with words: not just the words of the literary chef d’oeuvre Jack attempts to write, but also the film’s frequent intertitles, and the fetish word REDRUM” (murder in mirror-writing) that preoccupies Danny.

The closing inscription appears to explain what has happened to Jack. Until watching the film again recently I’d always assumed that, after his ordeal in the haunted palace, Jack had been absorbed into the hotel, another sacrificial victim earning his place at the Overlook’s eternal thé dansant of the damned. At the Overlook, it’s always 4 July 1921 – although God knows exactly what happened that night. In fact, Jack Nicholson’s likeness literally has been absorbed into the picture: collaged into a 20s archive shot and matched to the photographic grain of the original.

Or you can look at it another way. Perhaps Jack hasn’t been absorbed – perhaps he has really been in the Overlook all along. As the ghostly butler Grady (Philip Stone) tells him during their chilling confrontation in the men’s toilet, “You’re the caretaker, sir. You’ve always been the caretaker.” Perhaps in some earlier incarnation Jack really was around in 1921, and it’s his present-day self that is the shadow, the phantom photographic copy. But if his picture has been there all along, why has no one noticed it? After all, it’s right at the centre of the central picture on the wall, and the Torrances have had a painfully drawn-out winter of mind-numbing leisure in which to inspect every comer of the place. Is it just that, like Poe’s purloined letter, the thing in plain sight is the last thing you see? When you do see it, the effect is so unsettling because you realise the unthinkable was there under your nose – overlooked – the whole time.

However you interpret the photographic evidence with which the film singularly fails to settle its uncertainties, this strikes us as an uncanny ending to an uncanny film. One of the texts Kubrick and his co-writer, novelist Diane Johnson, referred to when adapting Stephen King’s novel was Freud’s 1919 essay ‘The “Uncanny”‘. The essay, which examines the troubling effect of certain elements in life and supernatural literature, defines the uncanny as “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” Or as Freud puts it, quoting Schelling, the uncanny is “something which ought to have remained hidden but which is brought to light.” The hidden brought to light: a theme common to ghost stories and one you’d expect to be prominent in a film called The Shining.

The final scene alone demonstrates what a rich source of perplexity The Shining offers. At first sight this is an extremely simple, even static film. A family move into a Colorado hotel for the winter so Dad can write his great literary work in peace while performing his function as caretaker. But the ancient blood-soaked visions recorded like old movie scenes in the hotel’s walls emerge, and Jack is possessed, driven homicidal. Or perhaps he’s crazy to begin with: the film’s central question, as Paul Mayersberg put it in a 1980 Sight and Sound article, is: “Does the place drive you crazy, or are you crazy to live in the place?”

It all seems simple enough – the Big Bad Wolf storms around with an axe, the Little Pigs (his snarling sobriquet for Wendy and Danny) escape. At the time of the film’s release many critics were unimpressed by this schema – Kubrick had put so much effort into his film, building vast sets at Elstree, making a 17-week shoot stretch to 46, and what was the result? A silly scare story – something that, it was remarked at the time, Roger Corman could have turned around in a fortnight.

But look beyond the simplicity and the Overlook reveals itself as a palace of paradox. There’s an unsettling tension about the film’s austerity on the one hand (there’s something positively Racinian about the unities of this grand-scale chamber piece) and dizzying excess on the other. Kubrick’s apparent disdainful detachment from the horror genre shows itself in the systematic flouting of a key convention: instead of an old dark house, a modern brightly lit one. But when Kubrick does lay on ghoulie business it’s almost farcically extreme: a festering bogeywoman in the bathroom, a courteous blood-soaked reveller, and instead of the time-honoured scarlet drips, tidal waves of gore burst from lifts and flood corridors (and what rich, dark claret it is). Then there’s the acting – perfectly naturalistic and restrained at the start, building towards animal eyerolling, as Duvall becomes the shrieking incarnation of panic, and Nicholson, in a performance that has defined him for life, snarls, grinds his jaw and occasionally tempers his Neanderthal psychosis with tics that look like Oliver Hardy impersonations (check out his first scene at the haunted bar).

Even if the drama appears straightforward, there’s the matter of the unearthly stage it’s enacted on – the hotel itself, with its extraordinary atmospherics. Hotel manager Ullman (Barry Nelson) welcomes Jack by telling him how a former caretaker, Charles Grady, went crazy and chopped up his family: the problem was cabin fever, the result of confinement in isolation. Not only do the Torrances suffer cabin fever but Kubrick wants us to as well. The Shining makes us inhabit every comer of the painstakingly constructed hotel sets, and the way the film guides us along corridors, around corners, up staircases – thanks to Garrett Brown’s revolutionary new gizmo the Steadicam – makes us feel we know every inch of the place, even (especially) the sound of its silences.

The Overlook is no less a maze than the leafy one that stands in its garden: the whole film is informed by a disorienting inversion of inner and outer spaces. The spacious Colorado Lounge is steeped in daylight – suffused at first with autumnal glow, then later, in the unnerving shot of a snarling, transfixed Jack, with the same cold blue light we’ve seen outside in the snow. The most unsettling of these inversions comes when the camera follows Wendy out through the hotel door and into the snow outside. But it feels instead as if she’s entering a giant freezer like the one she’s already visited in the hotel’s kitchen – and, of course, it’s just that, a huge snowscape set constructed at Elstree, itself bounded in isolation.

Then there’s the eerie sense of things closing in, reducing, paring themselves to the essential. We feel it in the film’s time scheme, which seems elastic and amorphous but is mapped out more and more precisely in a succession of intertitles: “A Month Later”, “Tuesday”, “Sunday”, “4pm” and finally the last shot, which brings us to a specific but eternal moment outside time. A further sense of reduction comes from Kubrick’s treatment of Stephen King’s baggy, prolix novel (416 closely typeset pages in the current NEL paperback not bad for a book about writer’s block). Kubrick and Johnson have stripped out swathes of King’s references to the outside world including much exposition of Jack’s and Wendy’s unhappy family histories and Jack’s alcoholism, disastrous teaching career and uneasy relationship with a benevolent patron. They also lose copious specifics about the various deaths, scandals and murders that mark the Overlook’s history, not to mention many of King’s supernatural sideshows such as the animated topiary animals, replaced (ostensibly because the special effects were unworkable) by the maze. In the film, events happen largely behind closed doors, and the backstory – and the import of Danny’s telepathic “shining” – have to be inferred. (Anyone with a taste for more literal King spookery is referred to the laborious, FX-laden television mini-series adaptation of the novel, directed by Mick Garris, which King, frustrated by Kubrick’s treatment, wrote and produced.)

A further reduction is the film’s own curious shrinkage. It was first shown in the US at a running length of 146 minutes, but in the early weeks of release Kubrick excised a two-minute sequence from the end, in which Wendy was visited in hospital by Ullman. By the time the film reached the UK it had lost another 25 minutes including a tableau of cobwebbed skeletons discovered by Wendy as she wanders through the hotel towards the end of the film. The cut referred to in this article is the extant UK version currently available on video. This version seems to be The Shining stripped to the bone, and the elision and spareness are surely what make the film so effective – there’s a tangible sense of things closing in towards the essential, just as the closing shot tracks in on its final revelation.

The dominating presence of the Overlook Hotel – designed by Roy Walker as a composite of American hotels visited in the course of research – is an extraordinary vindication of the value of mise en scène. It’s a real, complex space that we don’t just see but come to virtually inhabit. The confinement is palpable: horror cinema is an art of claustrophobia, making us loath to stay in the cinema but unable to leave. Yet it’s combined with a sort of agoraphobia – we are as frightened of the hotel’s cavernous vastness as of its corridors’ enclosure. When Jack attempts to write in the huge Colorado Lounge we wonder what’s getting to him more – being imprisoned in his own head or being adrift at his desk as though at sea. Wendy’s reaction on arrival is “Just like a ghost ship, huh?”, and the Gold Room full of revenant partygoers is the very image of the Ship of Fools, still carousing while the boat goes down in a tide of blood.

The film’s subtexts resonate in the vastness as in a sound box. It’s the space itself that allows so many thematic strands to emerge from an ostensibly simple narrative, whether or not they are explicitly delineated. The copious critical literature on The Shining reads it variously as a commentary on the breakdown of the family, the crisis of masculinity, the state of modem America and its ideologies, sexism, racism and the dominance of big business. But what gives the film its curiously resistant, opaque feel – which makes it possible for critics to conclude that The Shining is really about nothing at all, simply a botched genre job – is the fact that this is a film about the experience of watching The Shining. The subject is not only possession but film as possession; seeing the Torrances in their different ways bewitched by the Overlook, we can’t help wondering what’s happening to us as we watch them. Are we as sceptical of the hotel’s legends as Jack seems to be when first told of the Grady killings? Or are we transfixed, eyes gaping like Danny? A recurring question in horror cinema is how our reactions are affected by seeing other people in the grip of terror: are we terrified out of empathy, or do we distance ourselves with cool scepticism? (Wes Craven’s Scream films are entirely about this question.)

The film does a lot to discount its more conventional horrors. Hallorann describes the Overlook’s lingering images of past horrors (photographs or metaphors?) with disarming domesticity, as being “like burned toast”. The first such picture Danny sees – in a famous shot that echoes Diane Arbus’ photographs – is of the two murdered Grady girls, who invite him to come and play “for ever and ever and ever”. This image is intercut with shots of the girls lying dead and blood-stained, but we’re immediately warned to take these horrors lightly; Danny’s guardian spirit Tony tells him, “It’s just like pictures in a book, Danny. It isn’t real.”

Kubrick by turns discredits the visions and has them startle us out of our wits: one minute throwing them at us in a sudden cut or shock zoom, the next denouncing them as a mere magic-lantern illusion (the little girls, like the blood-steeped bon viveur who raises his glass to Wendy, are first shown dead-on frontally, as if projected on a screen). Wendy’s bizarre vision of a dapper toff caught in flagrante delicto with a figure in a dog costume is framed in a doorway – another picture rather than a manifestation integrated into the real. In a sequence shortly afterwards, in the US version only, she comes upon a group of seated skeletons in a dark, cobwebbed lounge apparently lit by moonlight from outside – inexplicable and incongruous lighting since the rest of the Overlook is suffused with a warm, brownish glow, eerily suggestive of dried blood. It’s as if, in this scene, the house itself has gathered together its dustiest genre props for a conventionally spooky haunted-house tableau (mort rather than vivant).

The shining – the telepathic power to perceive and project – nominally belongs to Danny, but is shared by the Overlook itself, as much a cinema as a hotel, its gold and orange corridors suggesting the ambience of an archaic movie palace. (As Johnson said in a 1981 Positif interview: “In a certain sense, it’s the hotel that sees the events: the hotel is the camera and the narrator.”) But the Overlook is also a place where people come to let their imagination run riot, to make movies in their head – and sometimes to transmit them into the world. Jack attempts that in his writing, but Danny does it much more successfully. Whether or not Danny’s telepathy brings the Overlook’s spectres to life, what’s certain is that the boy is actually able to transmit them. The film’s big horror routine – Jack’s encounter in Room 237 with an etiolated vamp turned suppurating hag – might not really be happening at all (Jack subsequently tells Wendy he’s seen nothing in the room), but may in its entirety be a hyperimaginative boy’s visual metaphor for the urgency of events. There’s a stark difference between the shots of Danny wide-eyed in shock elsewhere in the film and the images of him here, in a dribbling trance, not so much transfixed as in a state of extreme concentration, as if he’s at once composing the images and sending them. We already know Danny is an adept of television culture – he is first seen watching Roadrunner cartoons, a role model for his evasion of Jack’s Coyote.

Wendy is somewhat sidelined in this dynamic – a screaming, gawping bystander who never gets the measure of what she sees. The thoroughly bad deal she receives is due in no small part to Kubrick’s difficult on-set relationship with Duvall, resulting in what seems an unfairly punitive attitude to her character. In the minutes missing from the UK version Duvall fleshes out Wendy’s character considerably: she has a number of key scenes with Danny, a nervous soliloquy musing about escape from the hotel and a scene back in Boulder where she tells a doctor (Anne Jackson) how Danny was once injured by a drunken Jack. Duvall’s twitchy, pained performance here, evoking a complex mixture of confession, guilt and denial, makes it clear how much energy Wendy devotes to keeping the household together. With these scenes cut she is effectively landed with the role of the naive movie-watcher, one who never learns to see through the shoddiness of horror images but just screams uncritically at everything she’s shown: she’s “a confirmed ghost-story and horror-film addict”, Jack announces, and for those viewers Kubrick shows only disdain. (The Shining was made at a time when consumption of horror was most often thought to turn viewers into credulous rubes, rather than to hone their critical skills as it is today in the intertextual age of The Faculty.)

It’s tempting to read The Shining as an Oedipal struggle not just between generations but between Jack’s culture of the written word and Danny’s culture of images. The written word comes off pretty badly. It’s understandable that writers often get a bad deal from cinema: offering the possibility of madness and distraction, not writing (cf. Barton Fink) is a more fruitful movie theme than writing. The prospect of generating meaningful words seems hopeless in The Shining, perhaps as a corrective to King, who accumulates all too many.

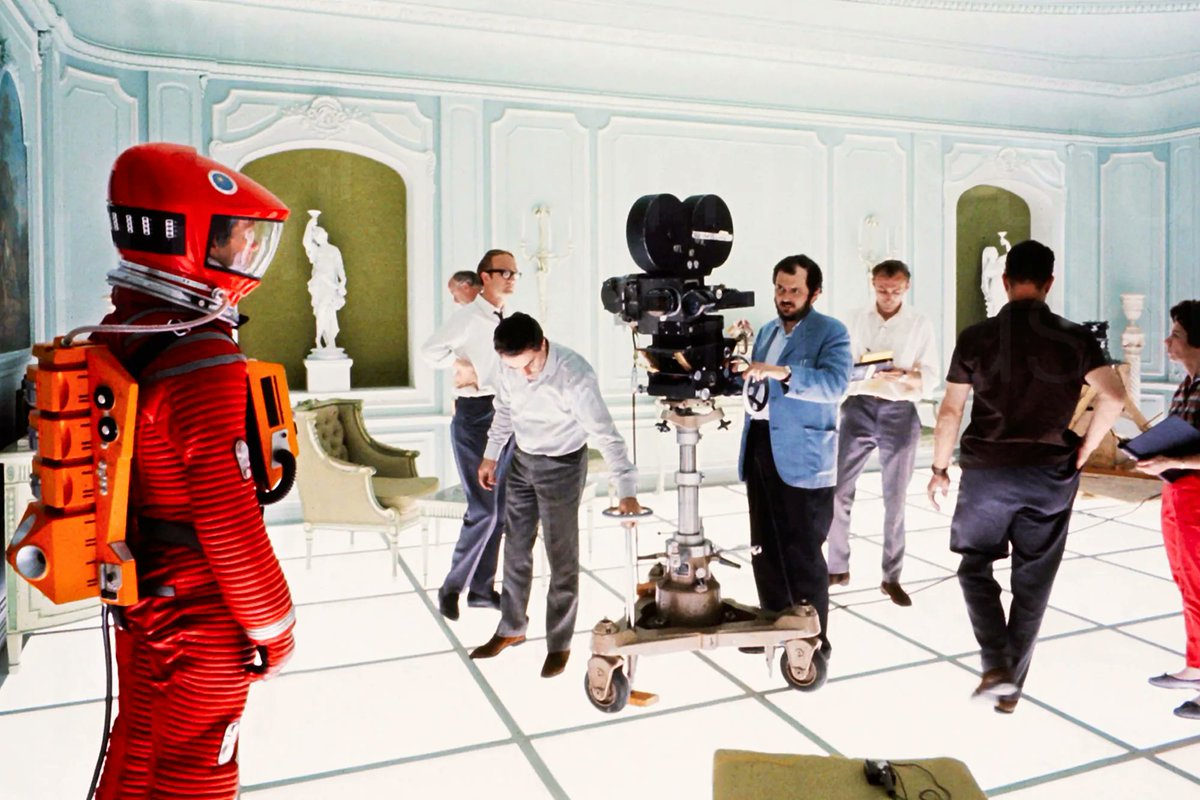

Much has been said about Jack’s agonised travails as an image of Kubrick himself, and about the Overlook as a Kubrickian fortress of solitude like the space stations and rococo bedroom in 2001. But you can’t help wondering what Jack’s writing actually entails. He’s not necessarily there to create anything so mundane as a novel or a play – he’s “outlining a new writing project”, he tells Ullman. A new form of writing? One that isn’t necessarily limited to words carrying meaning? As he snarlingly informs Wendy, whether he’s typing, or not typing, or whatever the fuck he’s doing, he’s writing. And maybe the work gets done, despite appearances. The film’s most shocking moment is Wendy’s discovery of his slab of completed text – a stack of sheets typed with the words “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” over and over again in countless permutations: neatly double-spaced, organised in chunks, blocks, script form, verse form. Who’s to say this isn’t Jack’s definitive oeuvre – a Mallarmé-esque supertext that transcends literal content but creates meaning in strictly typographic form, in the performance of writing? What is it but a muscular and entirely accurate portrait of Jack, a faithful recording of his being?.

Jack also uses the written word to more mundane purpose – to sign his “contract” with the Overlook. “I gave my word,” he says, which we take to mean ‘gave his soul’ in the traditional Faustian sense. But maybe he means it more literally – by the end of the film he has renounced language entirely, pursuing Danny through the maze with an inarticulate animal roar. What he has entered into is a conventional business deal that places commercial obligation – the provision of services – over the unspoken contract of compassion and empathy that he seems to have neglected to sign with his family. Jack’s the loser: it soon becomes clear that the Overlook has reneged on its part of the deal from the start and conned Jack into doing a job he hasn’t bargained for.

The Overlook doesn’t want a neat caretaker, let alone a resident writer. It likes to reduce clever people to menials: look at Grady the butler, clearly a cultivated man through and through. The Overlook wants Jack as a clown, an entertainer for the bored spooks wintering up there alone. The privileges Jack is accorded (tolerance from Lloyd the sepulchral barman, limitless credit from the management) are the sort of deals given the in-house cabaret act. The ghouls are assembled to watch Jack wrestle with his demons and lose: this is effectively Kubrick’s second gladiator movie, after Spartacus (1960).

Hence Jack’s reward, after his defeat: a central place among who knows how many other doomed variety acts on the Overlook’s wall of fame. He’s added to the bill on the Overlook’s everlasting big night back in 1921. And, having done his stuff, he deserves an acknowledgement from us too as we get our coats and go. And that’s exactly what he gets. The last thing we hear in the film – although we’re probably half way to the foyer by then – after the echoing strains of ‘Midnight with the Stars and You’ is a round of polite applause over the end credits, which then dies down as the ghouls too leave the theatre.

Sight and Sound, September 1999, pp. 38-39

1 thought on “THE SHINING: RESIDENT PHANTOMS”

So, what does the ending mean?

In a rare interview with filmmaker Jun’ichi Yao, Kubrick explained: “It’s supposed to suggest a kind of evil reincarnation cycle, where he [Jack] is part of the hotel’s history, just as in the men’s room, he’s talking to the former caretaker [Grady], the ghost of the former caretaker, who says to him, ‘you are the caretaker; you’ve always been the caretaker, I should know I’ve always been here’”. Continuing, the filmmaker adds, “One is merely suggesting some kind of endless cycle of this evil reincarnation”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fVlXbS0SNqk