Masterpiece: Some Like It Hot (1959)

Simon Braund hails the enduring appeal of Wilder’s classic comedy, and gives credit to that magic final ingredient — Marilyn Monroe…

Simon Braund hails the enduring appeal of Wilder’s classic comedy, and gives credit to that magic final ingredient — Marilyn Monroe…

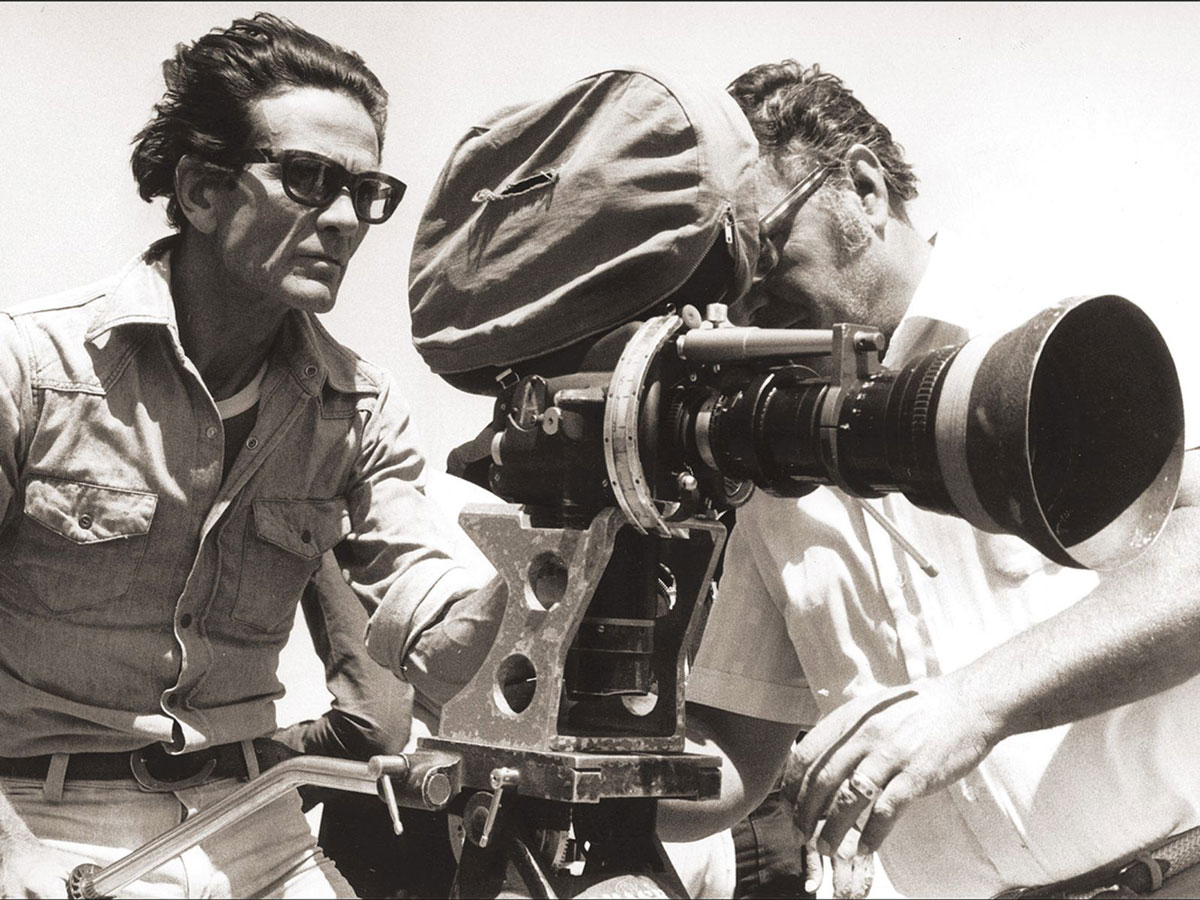

The distinction I make between cinema of prose and cinema of poetry is not a distinction of value, it is a purely technical distinction. If I had to define this distinction I would say that in cinema of prose the protagonists, as in classical novels, are the characters, their history and their environment. In cinema of poetry, on the other hand, the protagonist is style.

Barry Lyndon mette in scena una società violenta, ferocemente classista, dove l’avventuriero gode di una libertà effimera e viene presto emarginato e distrutto. Arricchito dalla più bella fotografia che si sia vista al cinema, il film comunica con stoicismo un sentimento amaro dell’esistenza e della storia.

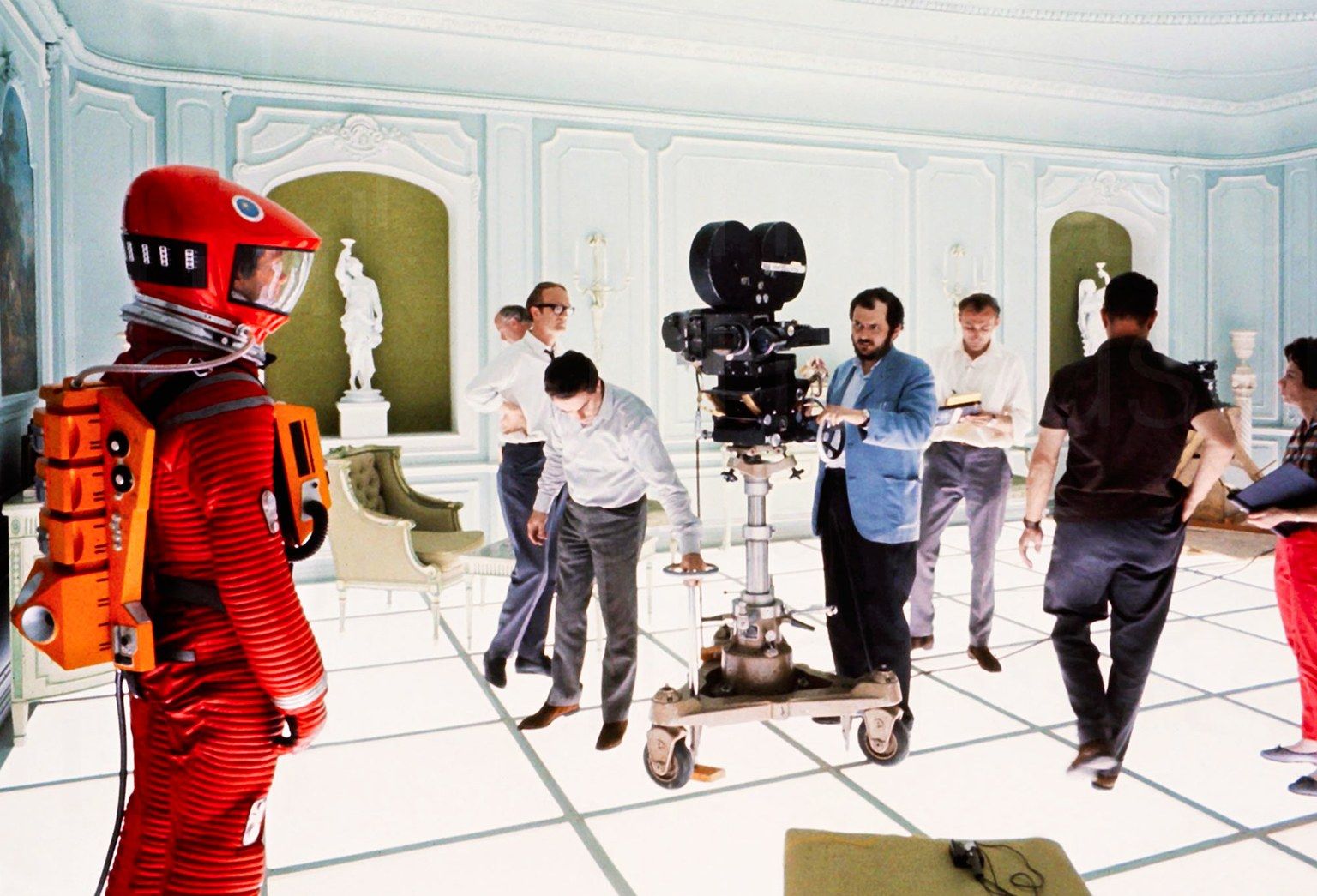

Stanley Kubrick ha equamente ripartito il film tra un’immagine agghiacciante del futuro e il grigiore dell’establishment antiquato e cadente. Per ripeterci che l’uomo non può migliorare, il regista ha fatto riecheggiare il romanzo di Burgess in una cassa armonica dagli effetti stereofonici.

Paths of Glory finds Kubrick dealing in the wider realm of ideas with a relevance to man and society. Without casting off any of his innate irony and skepticism, the director declares his allegiance to his fellow men.

Kael defines the role of the critic as messianic: to help see what is in the work, what is in it that shouldn’t be, what is not in it that could be. He is a good critic if he helps people understand more about the work than they could see for themselves

The Godfather bore witness to the bitter truth: evil, hydra-headed, renews itself and triumphs in the end; in America, the Corleones win.

Empire sent Deputy News Editor Nick de Semiyen on an inter-continental journey to meet with the legendary funnyman in Amsterdam and then LA. There’s a steely focus behind the jovial veneer — he’s not exactly Robin Williams — but the man’s genial nature and precision wit make a few hours in his company fly by.

Dopo 40 anni di collaborazioni cinematografiche, Pedro Almodóvar ha affidato ad Antonio Banderas, il suo attore feticcio, la parte del suo alter ego nel suo nuovo film, Dolor y gloria.

Nell’anniversario della morte di Stanley Kubrick, torna nei cinema nella versione restaurata uno dei suoi capolavori, 2001: Odissea nello spazio

Bicycle Thieves remains among the most beloved films ever made, a heart-rending, poetic and compassionate rumination on the human condition that, as has often been said, invests the mundane tribulations of ordinary people with the power and pathos of Greek tragedy.

Pauline believed she had a clear-eyed view of Kubrick’s intentions. At the end of the picture, when Alex’s former victims turn on him and he reverts to his old, corrupt self, she grasped that Kubrick intended it as “a victory in which we share . . . the movie becomes a vindication of Alex, saying that the punk was a free human being and only the good Alex was a robot.”

Kubrick’s virtuosity as a filmmaker, and the range of his subjects, have served to disguise his near-obsessive concern with these two matters—the brutal brevity of the individual’s span on earth and the indifference of the spheres to that span, whatever its length, whatever achievements are recorded over its course.

Frank Capra is a brave man. He might be called a premature auteurist, since long before that critical theory was enunciated he believed that the director was the logical person to be the author of a movie. “One man, one film” was his credo and he was not modest about taking credit for his work.

Examined by any standards, those of 1936 or today, Mr. Deeds had or has to be regarded as pure wishful fantasy. Longfellow Deeds, the lanky hero whom Mr. Cooper so aptly played, was an amiable small-town bumpkin who candidly combined all the platitudinous pieties and virtues of an idealized Boy Scout.

Keira Knightley e Alexander Skarsgard ci danno dentro in inconsistente film ambientato nella seconda guerra mondiale

Driven by Michael Moore’s sincere humanism, Sicko is a devastating, convincing, and very entertaining documentary about the state of America’s health care.

Watership Down (1972) came into being as a brief, whimsical tale of rabbits told to amuse Richard Adams’s daughters. Its popularity with them was such that finally he was forced to work out the ramifications of his simple story, and the novel took shape. A labor of love, it was inspired by the desire to tell a good story. The tone of the story reflects this attitude.

Alan Morrison argues that there’s more to Nicolas Roeg’s British classic “Don’t Look Now” than the best sex scene in the history of cinema

It may not be the spiritual forerunner to Independence Day and Mars Attacks! — the space-travellers here actually do come in peace — but this 1951 classic’s jittery mood, epic sweep and stylised looks inspired those and plenty of other alien-arrival flicks.

Brazil is a tragicomedy about the relationship between imagination and fantasy, and about the ability of a society (“somewhere in the 20th century,” as the opening sequence informs us) to constantly transform the energy of the former into the dead weight of the latter.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!