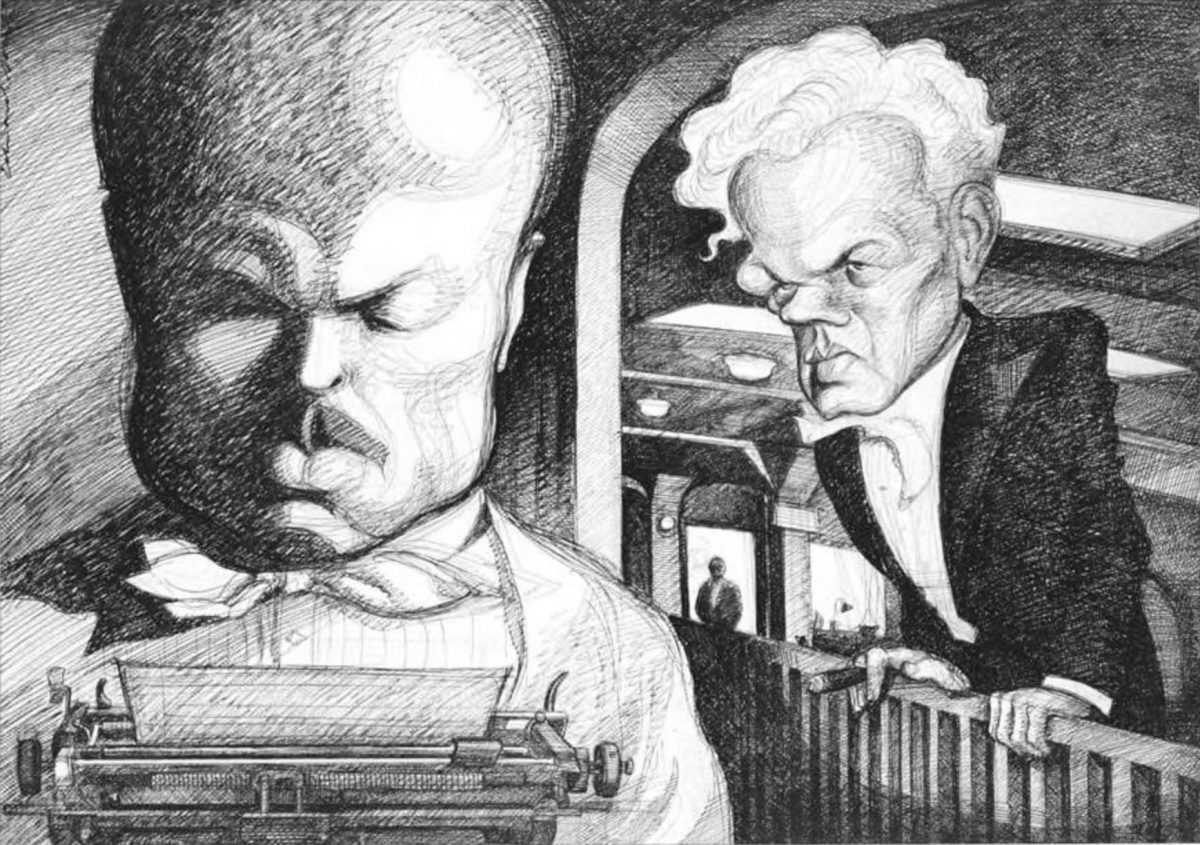

Even for the flamboyant world of Hollywood, Herman Mankiewicz was an extravagant figure. He is probably best known as the primary author of Citizen Kane, one of the masterpieces of filmmaking in America. But during the 1930’s and 1940’s he became a living legend, for Mank was larger than life—more brilliant in his wit, learning, and conversation, more freewheeling in his capers, greater in the scale of his faults and in the self-destructiveness of his fall. He was that enormously romantic figure—the incandescent cutup who lived his life as one continuous escapade.

I only put my talent into my writing; my genius I reserved for my life.

—Oscar Wilde

It does something to you, if from the time you’re old enough to see, you get standards set for you, and ideals, and ambitions, that you . . . well, you know you aren’t up to them.

—Herman Mankiewicz, Script for Christmas Holiday

In early 1940 Herman Mankiewicz began the first draft of Citizen Kane. He dictated it to a secretary, as was his habit. Rita Alexander remembers: “He began with the title, the description of the scene, the indications of the camera movement, the dialogue, and so on. It was really extraordinary. It all came out not fast, not slow—at a continued pace as though he had it all in his mind.”

When Herman first mentioned “rosebud,” she asked, “Who is rosebud?”

“It isn’t a who, it’s an it,” said Herman.

“What is rosebud?” asked Rita Alexander.

“It’s a sled,” said Herman.

Citizen Kane is the imaginary biography of a newspaper tycoon and American sultan, Charles Foster Kane. The movie begins with his death, virtually alone, in his vast, self-created castle, Xanadu. Kane’s lips, filling the movie screen, mouth his last word: “rosebud.” A newsreel company, putting together an obituary on Kane, dispatches a reporter to find the meaning of “rosebud.” In the process the reporter learns the details of Kane’s life, including the fact that his parents ran a boardinghouse in Colorado. A lodger absconded leaving Mrs. Kane apparently worthless stock in a gold mine, which became the fabulous Colorado Lode. Mrs. Kane, feeling unequal to raising a child destined for a king’s wealth, signs her five-year-old son over to a bank which will rear him and manage his inheritance. The boy’s future guardian, Thatcher, an officer of the bank, arrives to take him away to New York. There is a snowstorm, and the child Kane is happily playing with a sled and a snowman. When young Kane is told he will leave with Thatcher, the boy hits him in the stomach with the sled.

The reporter searching for “rosebud” reads Thatcher’s memoirs and interviews four people who were close to Kane: his oldest friend, his office manager, his butler, and his second wife. None of them can explain “rosebud.” But their memories show Kane as a man destroyed by wealth and the inability to love. Then, after Kane’s death, while his vast accumulation of art treasures is catalogued, the valueless relics of his life are burned. The boyhood sled is flung into a furnace, and the consuming flames light up the rosebud painted on its wooden top—Kane’s symbol of the childhood and the parental love that was denied him.

* * *

Herman Mankiewicz must have identified powerfully with Kane and with “rosebud.” He, too, had deeply bitter feelings about his boyhood in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Those years created a youth and man of resilient ambition but riddled with self-doubts—and almost immune to normal restraints. He approached life as a prolonged escapade. Even the wife he loved, the redoubtable Sara, was only a sometime brake. Eager for adventure, he took her as a bride to 1920’s Berlin, claiming he had a foreign correspondent job with the Chicago Tribune. Soon he had to confess the job did not exist. Then, to refuel his self-esteem, he pretended that the Tribune, after all, had hired him on the spot.

Rosebud, the symbol of Herman’s damaging childhood, was not a sled. It was a bicycle. When he was ten, a bike, that vehicle intrinsic to childhood freedom, was promised to Herman for Christmas. In a thrill of anticipation, he came downstairs on Christmas morning. There was no bike. His father, perhaps short of money, perhaps blind to its importance, had not yet bought it. Weeks later Herman got his bike and careened with his friends, feet on handlebars, down the tree-shaded streets.

Herman was a mischievous child. One day after some misdemeanor, Herman was confined to the house by his mother. To keep him there during her absence, she hid the long stockings he needed for his knickers. Herman went to his mother’s room, put on a pair of her stockings, got on his bike, and rode off to the Wilkes-Barre public library, where he loved to browse among the shelves and to read for hours. When he came out, the precious bike was gone—stolen. Herman’s punishment was permanent. His father never bought him another bike. His mother answered Herman’s pleas by telling him it was all his own fault. Kane’s deathbed cry for “rosebud” and his unlived boyhood was also Herman’s call to fate, “Where is my bike?”

Herman’s bike meant freedom both from his father, the primary cause of his early scars, and from his home, where he did not get enough love.

* * *

There but for the grace of God goes God.

—Herman Mankiewicz on Orson Welles

In true Hollywood style Herman, down and out, suddenly fulfilled his potential. For once, his knowledge, intelligence, and anger were used on a single creative effort, the screenplay for Citizen Kane. In 1962 Kane was voted the best film in motion-picture history by seventy critics from eleven nations. Even in the 1970’s, when film had replaced the novel as a major artistic force, a group of American producers and critics chose Kane and Gone with the Wind as the two most significant movies in U.S. film history. Orson Welles was Kane‘s producer, director, star, and dominating force, but the movie would never have existed without Herman Mankiewicz.

The writer’s credit reads “Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles.” However, the authorship of Citizen Kane has become one of film history’s major controversies. And the question of who did what and how much opens up an extraordinary subdrama of jostling egos. The question was raised by critic Pauline Kael in her 1971 New Yorker article titled “Raising Kane.” She stated that Herman wrote virtually the entire script and that Welles systematically usurped the credit. Though he admits he had important help from Herman, Welles indignantly insists that he was the primary author not only of the script but the original idea. John Houseman, Welles’s onetime partner and Herman’s editor on the first draft of Kane, has written a memoir called Run Through. While describing his work with Herman, Houseman strongly implies that he himself was a crucial influence in the creation of Kane. Speaking vociferously from the grave, Herman claims sole authorship. For example, in a letter to his father after Kane opened, he said, “There is hardly a comma that I did not write.”

Pauline Kael calls Kane “a shallow masterpiece” but nevertheless “an American triumph” which “manages to create something aesthetically exciting and durable out of the playfulness of American muckraking satire.” The story of Charlie Kane is told by the interlocking recollections of the five witnesses, presented in interviews and dramatized flashbacks. The episodes are arranged independent of chronology, moving back and forth in time. Gradually, like parts of a puzzle fitting together piece by piece—here, there—these memories complete a mosaic portrait of Kane, a man destroyed by wealth and the inability to love. Perhaps no movie script has ever been so complex, yet such a marvel of engineering which meshes its ideas, action, techniques into a satisfying and consistent whole.

The critic Andrew Sarris sees the themes of Kane as “the debasement of the private personality of the public figure, and the crushing weight of materialism.” Welles himself says, “The essential story of Kane is of someone who is raised without love or even human attention, and inherits an incredible fortune, and spends it—having himself no talents.”

The saga of the Kane script, searched out like another rosebud in a thicket of claims and contradictions, begins with an ironic fact. The conception and creation of Citizen Kane depended entirely on a series of failures and fiascos. And Mankiewicz, Welles, and Houseman all came to their various involvements with Kane because of an accident, a piece of tragicomic bad luck in the disorderly downward progression of Herman’s life.

The day Herman was fired from MGM and discredited at all the studios, he optimistically recited to Sara the wonderful movie and play ideas that were going to resuscitate him. Perhaps fate had at last freed him from pernicious Hollywood. He talked about going to New York to find a job and move east permanently. Perhaps Kaufman would collaborate again. He said that a young screenwriter named Tommy Phipps, the nephew of Lady Astor, was driving to New York and had invited him to ride along. Sara agreed. The next day, September 8, 1939, carrying some cash borrowed from Joe, Herman climbed into Phipps’s Buick convertible, and they departed.

Shortly thereafter Sara opened the financial statement Herman had left behind. He was badly overdrawn at the bank and had no income. He had a Morris Plan loan of $4,200, a loan on his furniture, and numerous personal debts. Joe took charge: Sam Jaffe lent money, Professor Mankiewicz sent $500, and Erna $1,000, and the Aaronsons contributed.

While Joe and Sam and a lawyer were conferring, Herman and Tommy Phipps were whizzing through the California sunshine toward the desert leg of their journey. Phipps was also leaving Los Angeles because of a catastrophe, a severed romance with a girl named Ethel. One could argue that it was Phipps’s broken heart that brought about Citizen Kane.

Ethel had sent Phipps a departure present accompanied by the tantalizingly unpunctuated note: “Take good care of yourself always Ethel.” That first day on the road was dominated by the word “always.” Herman sat listening to Phipps’s monologue debate on what “always” meant: whether or not it was a clue that after all, Ethel loved him. “And I was to remember,” Herman recounted, “that she was not the kind of girl who could lightly write ‘always Ethel.’ If she meant just ‘Ethel,’ she would write ‘Ethel.’ The second day was dominated by the word ‘good.’ I should understand,” Herman said, “that if a cultured girl like Ethel wanted to say, ‘Take good care of yourself,’ then that was what she would write and not ‘take care of yourself’ because if she meant ‘take care of yourself,’ she would write ‘take care of yourself’ and not ‘take good care of yourself.’ ”

That evening, driving in the rain, Phipps turned on the radio. Every tune reminded him of Ethel. “Little White Lies” was the song an orchestra had played the first night they met. Songs evoked fights and reconciliations, their first dance, anniversaries, even a miserable time away from Ethel. In the passion of his torment the teary Phipps was driving faster and faster. The car skidded on a curve, hit a culvert post, plunged over an embankment, turned over.

Phipps, unconscious, had a broken collarbone. Herman was pinned under the car, his leg broken in three places, a deep cut extending from above one eyebrow to the back of his neck. And Herman always swore that as the car rocketed from the road, he saw written in letters of fire across Tommy Phipps’s forehead, “She’ll be sorry when she hears about this.”

Returned to Los Angeles, Herman lay on his back for a month in the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, his leg elevated in traction, “somewhat,” said Herman, “in the posture of a lower-class Klondike whore.” From the professor Herman received, by letter, a dose of advice and inspiration:

Kopf hoch [head high]—I am not going to quote for you the proverbial saying of the silver lining which every cloud has, of the sunshine which follows rain, of the promise that every road has a turn—but I say this to you: Let the past bury the past, and let it be buried so deep that there is no chance of a resurrection. Eyes that do not turn backwards do not see any neurosis. There is a future of promise ahead of you.

Among Herman’s visitors was a friend from New York, Orson Welles. They had met at lunch at “21” when Welles was the wonderboy of Broadway, staging in partnership with John Houseman one adventurous hit after another. Houseman remembers the day that Welles met Herman in the late 1930’s and told about “this amazingly civilized and charming man.” Houseman adds, “I can just see them there at lunch together, magicians and highbinders at work on each other, vying with each other in wit and savoir faire and mutual appreciation! Both came away enchanted and convinced that, between them, they were the two most dashing and gallantly intelligent gentlemen in the Western world! And they were not far wrong.”

When Welles found Herman in the hospital, both physically and financially prostrate, he decided to help him. Welles offered Herman a job adapting literary classics for his Mercury Theater radio show. Herman would get no credit; as a publicity device all the radio shows were billed as written, produced, directed by Orson Welles. But Herman would receive $200 a script. Welles recalls, “I felt it would be useless, because of Mank’s general uselessness many times in the studios. But I thought, ‘Well see what comes up.’ ” What did come up, eventually, was Citizen Kane.

Herman was immediately demanding and impatient about the radio job, while Welles handled him with consummate and disarming charm. He assured Herman by wire that the sponsor had not yet approved the books for dramatization. “I can cover a couple of days with a neat alibi about a grounded plane and a washed out track,” Welles cabled. “But even I shrink from attempting a wholesome explanation for my conduct and whereabouts since I solemnly promised six days ago to let you hear from me in twenty-four hours. I give you my oath the only thing I could have done before this is keep up the decencies. Surely this is too much to ask. Much, much love to you. Orson.”

Herman began on the Mercury scripts in October, when he left the hospital and returned to Tower Road. To cool Herman as he lay incarcerated in a cast that was “like a boulder holding me down from my navel to my toes,” Margaret Sul-lavan had his room rigged with a makeshift air conditioner. She delivered long sticks for scratching under the cast. To facilitate the writing, Joe Mankiewicz brought around the lap board he himself used. Herman said, “What the hell do I want with that?”

One day Herman’s work was interrupted by a delegation of MGM writers who assembled at his bedside. They presented him with a large silver cigarette box engraved with all their names and the words “From Manky’s pals.” But to him it was like a gold watch given an old man when he retires. Herman wept after they left.

Herman wrote weekly Mercury scripts for Huckleberry Finn, Rip Van Winkle, Vanity Fair, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Dodsworth. “He was useful,” Welles says, “particularly with Houseman,” who was the editor on all the radio scripts and remembers editing Herman “rather harshly.” Herman grew a mustache and wrote his father: “One way or another, the Lord or the opposition—I am a little mixed up myself as to who has been keeping his eye on me of recent years—will provide. We are all in reasonably good spirits, though we are not down on our knees in a halleluiah chorus all day long, y’understand.”

To obtain income, Sara rented the Tower Road house and moved to southern Beverly Hills, where she rented a small house owned by the actor Laird Cregar. Orson Welles was a regular visitor there, coming in the evenings to enjoy Herman and confer on the radio scripts.

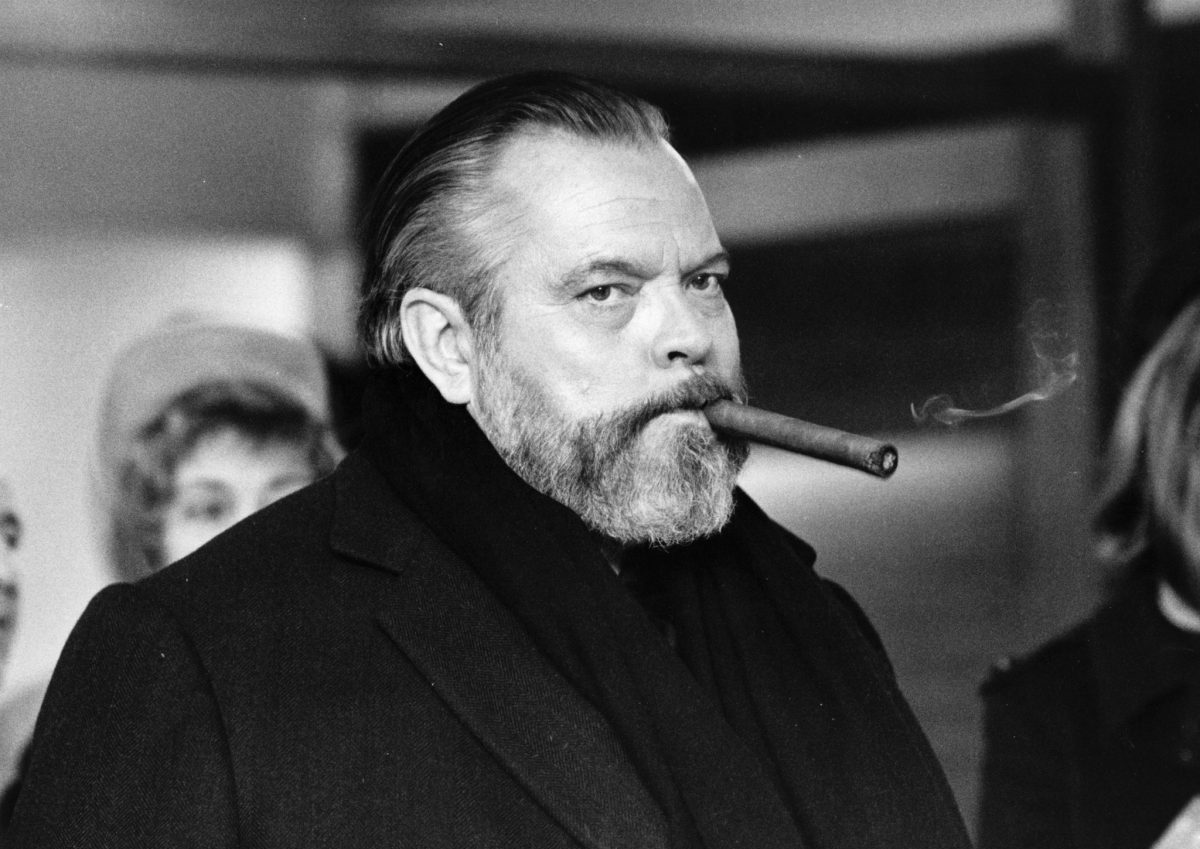

Welles was a stirringly handsome, flamboyant man, slightly rumpled, six feet three and a half inches tall. He had the same ravishing, irreverent charm as the young Charlie Kane. Geraldine Fitzgerald recalls, “We used to say that Orson had a ‘God’s-eye view,’ that he saw in you all the things that other people didn’t see, all the wonderments and brains and beauty and wit you had. But what was disturbing about this beautiful light was that it was rather like a lighthouse. When the beam turned, then somebody else was illuminated, and you were back in the darkness.”

At the tiny Roxbury house, Sara’s bed was the only place in the bedroom to sit while visiting Herman. She was usually propped up on pillows, reading. Welles would say, “Move over,” and lie down beside her. As he and Herman talked, goading each other with sarcasms, laughing uproariously, Welles would reach over and massage Sara’s neck. “He was fun,” Sara says. “Magnetic, absolutely.”

Though Herman’s 1939 accident was the immediate event that delivered Welles to the Roxbury room—and to Citizen Kane—Welles’s route to Hollywood began in the fall of 1937. The hit of that season was a one-act bare-stage version of Julius Caesar, directed by and starring Orson Welles, who then was only twenty-two. It launched a rampage of innovative successes by the repertory Mercury Theater, which Welles and John Houseman had founded.

Welles, working twenty-hour days, had the production ideas, designed sets, discovered actors like Joseph Cotten, directed all the plays, and starred in most of them. John Houseman contributed a superbly organized intelligence. A British- and French-educated Armenian and former London grain broker, Houseman raised the money and was the tasteful, practical enabler for Welles’s flashing imagination. Along with the stage productions, Welles and Houseman were creating their weekly radio dramatizations. “The War of the Worlds,” broadcast in 1938, panicked much of America into believing the Martians were landing in Grovers Mill, New Jersey.

There was, of course, a flash flood of publicity, including a Welles cover on Time magazine captioned “Marvelous Boy.” These stories all detailed his wunderkind credentials. His mother was a gifted musician, his lighthearted father a dissipated inventor who eventually committed suicide. At three Welles was reciting Shakespeare, at nine, performing magic, and at ten, discovering theater at the progressive Todd School, where he directed and starred in thirty Todd Players productions. At sixteen he acted a season with the Abbey Players in Dublin, Ireland, and at eighteen toured with Katharine Cornell. At twenty-one, he was ubiquitous on radio, doing the voice of Chocolate Pudding and historical characters in The March of Time and creating that invisible nemesis of evil the Shadow, hissing, “The seed of crime bears bitter fruit.”

But in the 1938-39 season Orson Welles’s success machine ran away with him. The last two Mercury productions, Danton’s Death and Five Kings, were disasters. The latter was a grandiose telescoping of five Shakespeare histories into one play. Time and money ran short. Hopelessly unready, Five Kings closed in Philadelphia. During the production a simmering disaffection between Welles and Houseman boiled over. Welles accused Houseman of sabotaging him. Houseman complained that Welles’s commitment was desultory, while his consumption of liquor, food, and women was awesome.

From this bitter failure, twenty-four-year-old Orson Welles traveled west in August 1939, the same month as Herman’s accident. Houseman came also, but much reduced in importance, and working mainly on the radio shows. Welles had an RKO contract that paid him $100,000 a year to write, direct, produce, and perform in four movies, one per year. The subjects were to be chosen by Welles and filmed without interference from RKO executives. But by September, when Welles went to visit Herman in the hospital, the Hollywood adventure was already turning sour.

The movie industry regarded Welles as a puffed-up wiseacre who deserved deflation. His contract enraged veteran filmmakers who could only dream of such carte blanche terms. Their irritation was further inflamed by Welles’s widely quoted remark during his first tour of RKO: “This is the biggest electric train a boy ever had.” When Welles invited the important names of Hollywood to a party, nobody came. An actor cut off Welles’s necktie at the Brown Derby. After Dorothy Parker, screenwriting in Hollywood, was introduced to Welles, she said, “It’s like meeting God without dying.” An actor named Gene Lockhart composed this doggerel:

Little Orson Annie’s come to our house to play,

An’ josh the motion pitchurs up and skeer the stars away,

An’ shoo the Laughtons off the lot an’ build the sets an’ sweep

An’ wind the film an’ write the talk an’ earn her board-an’-keep;

An’ all of us other acters, when our pitchur work is done,

We set around the Derby bar an’ has the mostest fun,

A-listenin’ to the me-tales ’at Annie tells about,

An’ the Gobblewelles’ll git YOU

Ef you DON’T WATCH OUT!

By November 1939, when Herman had begun writing Mercury radio scripts, Welles’s first movie project, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, had already been shelved by RKO as too difficult, too expensive, too uncommercial. Welles switched unenthusiastically to the less ambitious English thriller Smiler with a Knife. Welles wrote his own script but, not satisfied, hired Herman to doctor it.

Smiler put Welles on Herman’s own turf. For Herman, a self-destructive personality who worried that he was a washed-up hack, the chance to deflate this boy wonder proved irresistible. According to Welles, despite their genial relationship, Herman set out “to show that writing a film script was one thing I couldn’t do and also one thing I had better come to him for. He destroyed my confidence in the script, sneering at everything I did, saying, ‘That will never work.’ ”

By late December 1939 Welles was desperate. Smiler with a Knife was stalled, and his boy-wonder balloon was sagging down on top of him, to the delight of a grinning Hollywood. Welles began scratching for a new project. Both Hollywood outcasts, Welles and Herman had remained friends. They were already talking movie schemes and notions, that half fantasizing habitual to filmmakers. Now the brainstorming became a serious search for a plot idea—“just the two of us,” says Welles, “yelling at each other not too angrily”—while Herman fretfully poked his sticks under the cast, smoked, cursed, hollered needlessly for Sara, made Welles maneuver the bedpan, and writhed uncomfortably within his jungle gym of traction supports and exercise bars. Arguing, inventing, discarding, these two powerful, headstrong, dazzlingly articulate personalities thrashed toward Kane. Nobody knew who thought of what. To each man, everything seemed his own, perhaps because, like most great conceptions shared by two people, many of the basic elements already existed in the brains of both Mankiewicz and Welles.

For example, according to Welles, the initial, germinal idea for Kane was the movie’s plot device: creating a posthumous portrait of a man through the memories of his survivors. Welles says it was his idea. Geraldine Fitzgerald testifies that she planted it in his head. Waiting for her husband to join her in Hollywood, she was living at Welles’s house. One evening he was despondent over the abandonment of Smiler. So Geraldine Fitzgerald suggested the technique of telling a story from many points of view, a scheme for a play which had been in her mind for years. Soon after Kane was released, she said to Welles, “You know, that’s taken from that idea I gave you.”

“I don’t want you talking about it,” Welles said.

Geraldine Fitzgerald remembers: “I was so amazed because I thought he’d say, ‘Yes, isn’t it grand, the way it’s turned out?’ ”

However, Herman, who was forever hustling old, pet ideas to new audiences, had already used the multi-point-of-view device in the mid-1930’s. In the first act of his unproduced play The Tree Will Grow, news of Dillinger’s death is brought to the gangster’s family. The play is a complex and contradictory portrait gradually accumulated from the recollections of mother, father, friends, minister.

According to Herman, Kane was not triggered by the multiview idea. Herman once explained: “We discussed an unusual technique which was to show an actual guy in a March of Time and then find out about the guy.” Whether or not Kane originated with the newsreel thought, it was undoubtedly Welles’s contribution, a bonus of his two March of Time years, dramatizing the news to the pulse of “This week, as it must to all men. . . .”

Once they were launched, the two men began hunting a subject for their plot idea. They considered an industrialist, a soldier, even the life of Dumas. Herman said, “Then I told Welles that I would be interested in doing a picture based on Hearst and Marion Davies. I just kept on telling him everything about them. I was interested in them, and I went into all kinds of details.”

Suddenly Herman’s career had arrived at the center of his being. All that abstruse political reading and his whatnot shop of obscure Hearst lore merged with his movie professionalism. Says Don Mankiewicz, “I have always thought of his Hearst idea as a coin Pop carried around in his pocket, and then he finally spent it.” Welles himself does give Herman grudging, lukewarm credit for suggesting Hearst: “I suppose I would remember if it had been me.”

But, again, the thought was waiting in the heads of both men. Hearst was no stranger to Welles either. His father and Hearst had been young roisterers together. The Hearst friend and theater critic Ashton Stevens, eventually the model for the character Jed Leland, had been a sort of uncle to Welles. And in Hollywood of the 1930’s everybody, including Welles, was steeped in the wonders of the Hearst-Davies household.

The Hearst idea took various shapes. Welles wanted the individual recollections about the newspaper publisher to be radically different, exactly like the later Japanese film Rashomon. Several long sequences would be repeated exactly but acted differently so the same events and dialogue would give conflicting images of Kane. Herman, says Welles, wanted to build the movie around the mysterious shooting of Hollywood pioneer Thomas Ince aboard the Hearst yacht. The theme would be the examination of a murderer.

Herman himself said that he wanted to do a love story between a publisher and a girl. The publisher was to be patterned not only on Hearst, but on other tycoons who had similar relationships with women: Brulatour and Hope Hampton, McCormick and Ganna Walska, Samuel Insull and Gladys Wallis. In fact, this plan would have been a rudimentary version of the final Kane script.

Mankiewicz and Welles were developing exactly the explosive, convention-busting movie that Welles needed to restart his stalemated career. But Herman, apparently finished in Hollywood, was hardly a choice to salvage anybody else’s fortunes. Welles hired him anyway. “But,” he says, “I had no intention of Mank being the coauthor. None. Rightly or wrongly, I was still without self-doubt in my ability to write a film script. I thought Mank would do that anecdotal kind of thing about Hearst, give me a few ideas, fight me a little—and mainly would be as destructive as he had been in Smiler with a Knife. But I didn’t know how not to let him in since the essential idea of the many-sided thing had arisen in conversations with him. Of course, now I’m enormously grateful he existed.”

But as they hammered at the details of the plot, often disagreeing, everything that was best in Herman emerged and Welles was doubly trapped. “Mank took off and became extremely constructive, even where I didn’t agree, either at first or later,” Welles says. In late January 1940, more than a month after the initial idea, their arguments were becoming less and less creative. Welles decided that Herman should start writing. Herman agreed, but on one condition: He must have as editor John Houseman, who had broken with Welles and the Mercury Theater and retreated to New York. Welles flew to New York, and Houseman, excited by the idea, returned with him.

In Hollywood the three men had several long script conferences, thoroughly discussing everybody’s ideas. Around February 1, 1940, a two-car caravan set off, carrying Houseman, a secretary, a German nurse, reams of paper and source material, a bottle of pills supposed to combat Herman’s alcoholic thirst, and Herman himself, excited and groaning cheerfully in the rear of a limousine. Their destination was a vacation retreat called the Campbell Ranch, a group of low Spanish adobe buildings on the desert flat near Victorville, California. Herman and Houseman shared a two-bedroom, living-room guest cottage. No liquor was allowed at Campbell Ranch. “That appealed to me,” says Sara, who chose the place.

In that desert limbo Herman found the perfect circumstances in which he could function. He was quarantined from everything that had always plagued and immobilized him. Trapped in his cast, he could not go drinking. Studio ignoramuses were not degrading him. His family was not riddling him with guilt. There was little to do except write. Disputations and dissipations were not draining his energies and concentration. Herman was at peace.

The creativity in Herman was released. His self-doubts were eased and his confidence was bolstered by the presence of John Houseman, a challenging, analytical, perceptive man. Welles’s enormous abilities almost guaranteed success. And in Welles and Houseman, he finally had creative intelligence he could respect.

The opportunity to use that banked-up political-historical expertise and excitement, hitherto useless in Hollywood for anything but conversation, must have galvanized Herman. And he was psychologically charged to make his great effort. The car accident had been a brush with mortality, a reminder that pulling himself together could not be postponed forever. Lastly, he was powerfully motivated by the very circumstances which made his Kane pinnacle almost incredible. Herman was at rock bottom. This screenplay was almost certainly his last chance.

The secretary Sara found to work with Herman was a tall, handsome English girl named Rita Alexander, who lent her name to Susan Alexander in Kane. She had already been asked by Sara not to drive Herman to local saloons. And on her first visit to his room after lunch, Herman, in bed in his cast, said, “Mrs. Alexander, one of your duties is of a kind that I hesitate to ask of you, but we might just as well get down to it from the beginning.” He instructed her exactly on how to spoon bicarbonate into his mouth. After he had washed it down with water, he said, “You’ll excuse me if I have a little belch. That’s part of it.” And the belches rocked the room, while Rita laughed and he grinned sheepishly and offered courtly apologies.

Rita Alexander was the only dispassionate witness to the events at the Campbell Ranch. The routine she experienced included little of Houseman. “Mank was so on top of what he was doing,” she says, “that Houseman sort of ended up riding herd.” She and Herman began each day around ten in the morning with a horrendous decision. Should the dictation take place indoors with Herman in bed? Or now that Herman could hobble on crutches, should he sit in the arid, sunny little patio with his leg up on a stool? In either spot, Herman still contrived to procrastinate. Mrs. Alexander, taught by her father, was expert at cribbage, and Herman would interrupt the dictating with bouts played for small stakes. When, as usual, he kept losing, he suggested upping the stakes to recoup. But he still lost as he entertained Rita with anecdotes about Hollywood and the Round Table.

Herman’s main period of work was at night, after dinner, when he would dictate until midnight or 1 a.m. Rita would type up the pages immediately and return them to him before going to sleep. She asked how the story was going to turn out. “My dear Mrs. Alexander,” Herman said, “I don’t know. I’m making it up as I go along.”

The movie had needed a device to knit together the series of reminiscences into a plausible story line. Welles unenthusiastically offered a long quote from Coleridge. Herman substituted the search for “rosebud”—the sled young Kane was riding in a blizzard the day his mother bound him over to the bank executive, the symbol of the parental love denied to both Charlie Kane and Herman.

Recollections of his boyhood winters in Wilkes-Barre had been kept on the surface of Herman’s mind by a present Sara gave him, a glass ball paperweight containing a minute and wintry Swiss chalet and tree fixed forever in fluid. Herman would sit in his bedroom chair at Tower Road reflectively shaking the ball and watching the snow swirl up inside and settle down on the tiny scene. When Kane intoned, “Rosebud,” he held just such a ball, which then rolled from his lifeless hand and broke.

Out of some private corner of Herman’s memory came a gentle passage in the script, a moment of purity recollected which he gave to Kane’s factotum, Bernstein. “One day, back in 1896,” says Bernstein, “I was crossing over to Jersey on a ferry and as we pulled out there was another ferry pulling in . . . and on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on—and she was carrying a white parasol—and I only saw her for one second and she didn’t see me at all— but I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.” It is Welles’s favorite passage in Kane, and even he says Herman wrote it.

Orson Welles’s need for maximum credit for the Kane script has always been intense. At the time of the movie’s release in 1941, it was his vindication. The movie silenced the sneers and proved that he was indeed a boy genius. But the presence of Mankiewicz, a discredited, production-line writer, tarnished the triumph, harmed the symmetry and credibility of the Welles creative package described by Photoplay magazine: “A master craftsman who writes, produces, directs, acts.” It was the self-image which has been the cornerstone of the Welles ego. In time, Welles began dismissing Herman, telling interviewers, “Mankiewicz wrote several important scenes.”

Orson Welles specifically denies that Herman did the basic script for Kane. According to Welles, he himself wrote the first script, a mammoth, 300-page version, mainly dialogue, which Herman actually took with him to Victorville. “Though everything was reworked throughout, that contained the script as it developed. But apparently Mank never showed it to anybody.”

Welles had never before mentioned that massive piece of preliminary work. Hitherto he always based his claim of primary authorship on a very different story. That one has him writing his own, original screenplay, not before Victorville, but in parallel with Herman during Victorville. When the two scripts were finished, Welles combined them both.

It would have been strange if Welles had not put his Kane ideas on paper before Herman began writing. Moreover, he had chunks of Herman’s script to work on during Victorville. At least once, midway in Herman’s labors, Welles drove out and picked up all the pages to date. Reading them on the trip back to Los Angeles, he was outspokenly critical and began editing in the car. But as for an original script by Welles, there is only his word. Both Richard Wilson, his production assistant, and Richard Barr, the young aide-de-camp who ran his households and his errands, do not remember Welles, either before or during Herman’s stay in Victorville, working the number of weeks that such a writing job requires.

To evaluate Welles’s version of events, it is fair to consider him through the eyes of several men who worked on Kane, including Herman himself, who once wrote a treatment for a movie whose main character was Orson Welles, thinly disguised. “It is a real genius that he has,” wrote Herman, “and not any particular talent or collection of talents that have become fortified and outstanding through training. He is no Meglin Kiddie or premature Quiz Kid. And he provokes a hero worship that makes it possible to react to his bad behavior as if somebody else were guilty of it. You really have to excuse and forgive him. Why, God knows.”

The sound technician on Kane, James Stewart, remembers: “I’d work all day, and he’d make an appointment for eight o’clock at night to run rushes. Bob Wise, the cutter, and his assistant, Mark Robson, and myself were supposed to sit there and wait. He’d show up at midnight. No apologies. Just ‘Let’s get going now.’ And we’d work till three or four a.m. He’d have a jug of whiskey, but no offering it to anybody else in the room. Just for Orson. I don’t remember ever asking him for a favor. And I don’t think it would have occurred to anyone else.

“And I remember Bernie Herrmann—he composed the music for Kane—once slammed open the door to the dubbing stage and began telling us what he thought of Orson’s manners and methods. Then he slammed out again, and we all sat there a little stunned. Then the door burst open, and Bernie stuck his head in and said, ‘Remember, I’m not talking about Orson the artist.’ ” Stewart adds, “If Orson called up tomorrow and asked me to make a picture, I’d know I’d learn something. I’d say, ‘I’m with you.’ ”

Herman has written about Welles’s relationship to the truth. “He has a large number of genuine incredible experiences, but he also has an enormous assortment of lies. And the terrible thing is that anyone who believes he has caught him in a fantastic lie is apt to find that the fantastic story is the truth. And some simple unimportant statement, like just having bought an evening paper a half hour ago, is the lie.”

Paul Stewart, in addition to being the rehearsal director of the Mercury Theater radio shows and the actor who played Raymond, the butler, in Kane, had a social relationship with Welles. Stewart says, “Orson will say anything anywhere to anybody and look them straight in the eye. I remember when Orson was married to Rita Hayworth and we were sitting in the Cub Room of the Stork Club, and he says to me, ‘Will you do me a favor? Tell Rita how I jumped out of a plane and parachuted into Chicago when we were late for a broadcast.’

“And I said, ‘My God, I’d forgotten that,’ as though you could forget such a thing. And I went on, ‘The only thing is, I’m hazy on the details. I remember I was scared to death when I saw you do it.’ See, I’d done this number with him before.

“And Orson goes on to tell how we’re flying from New York to Chicago—you had to do it then in hops with small planes—and we stopped to refuel in Buffalo, and we refueled in Detroit and flew on to Chicago. And he tells Rita, ‘I was so late, I said to the pilot, “Circle Lincoln Park. I’m going to parachute in. I know I can make it.” ’

“And I looked at Rita,” Stewart says, “and she had some beautiful eyes and they were this big. And my wife—she knew. She kicked me under the table. He lies in other . . . in important things, too.” But Stewart also says, “With Welles he’s so brilliant, and he has a way of complimenting you and needing you. He phoned me personally in New York in September 1940 and asked me to play a part in a movie he was making. I said, ‘Sure.’ Didn’t even ask what the part was. I was so pleased to be friends with him again. I’d missed him in my life because every day with him was a day of last-minute preparation and plunging ahead and creating.”

While stating that Herman wrote the script and that he himself was only an editor, John Houseman nevertheless manages to claim a major role in the creation of the Kane structure, plot, and characters. In his memoir, Run Through, he describes a partnership of coarchitects:

We started with the image of a man—a giant, a tycoon, a glamour figure—we asked each other how this man got the way he was . . . we discovered what persons were . . . we learned what he did to them . . . we found the dramatic structure of the film gradually asserting . . . we reduced the number of principal witnesses to five—we were creating a vehicle suited to the personality and creative energy of a man only slightly less fabulous than. . . .

And the gospel according to Houseman describes a rigid routine which kept him astraddle the project but does not square with Rita Alexander’s memory. He tells how in the early morning he edited the previous day’s pages. Later in the living room-office he and Herman loudly argued about changes with Mrs. Alexander present and planned that day’s writing. Houseman wrote: “Once Mank had come to trust me, my editing, for all our disagreements, gave him more creative freedom than his own neurotic self-censorship.” By midafternoon Herman would retire for a nap, and Houseman and Rita Alexander would review her notes. After dinner, according to Houseman, they worked together until around ten, and then he went to bed while Herman continued dictating. Houseman’s impact on Herman’s thinking was undoubtedly important. But Run Through leaves the impression that Herman was in part a conduit for Houseman’s creative powers.

His need to claim a share in Kane is also great. In the Mercury Theater in New York, Houseman must ultimately have been galled by his role as Welles’s clear-eyed catalyst. He must have grown sick of subordinating his ego while believing, perhaps, that he was making the wonder-boy career possible. As one of Welles’s assistants once said, “There was only one umbrella, and that was Orson. You either enjoyed the shade or got out.”

And then in Hollywood Houseman was drastically demoted by Welles. Run Through diminishes Welles’s contribution to the Mercury Theater. The Kane script becomes Houseman’s proof that he was always a creative contributor in his own right, perhaps even the key to Welles’s great accomplishments. Welles says, “I have only one real enemy in my life that I know about, and that is John Houseman. Everything begins and ends with that hostility behind the mandarin benevolence.”

In a letter to Alexander Woollcott about Kane, Herman once said:

I feel it my modest duty to tell you that the conception of the story, the plot, the characters, the manner of telling the story and about 99 percent of the words are the exclusive creations of

Yours,

Mank.

In 1948 Herman, Welles, and RKO were sued for plagiarism by Ferdinand Lundberg, the author of Imperial Hearst. The suit was settled out of court. In a deposition Herman testified, “I would say I wrote a good 98 percent of the picture.”

Herman’s need for sole credit was overwhelming. Kane was proof that he was a major dramatist capable of a work of art. It was his shot at self-respect. In the Mankiewicz household, the fact of Herman’s authorship was irrevocably taken for granted.

But in the overall, historical puzzle of who did exactly what, Herman’s percentages seem implausible. Houseman, a fluent man of intellect, must have made valuable input. It is impossible to imagine that the protean Welles at the height of his powers was merely an admiring spectator. Moreover, Herman’s version ignores some five weeks of preliminary script discussions. Undoubtedly both Herman and Houseman arrived at the Campbell Ranch crammed with Welles’s ideas and wishes.

Nevertheless, Herman’s pride of authorship was justified. There is no corroborating evidence of early drafts by Orson Welles. Herman endured the writer’s special agony and faced the blank pages. Selecting from the ideas of Welles and Houseman, exercising his own imagination and knowledge, applying the experience of a decade of screenwriting, Herman assembled in his mind the roots and trunk of Kane. What Herman created in Victorville contained all the characters, nearly all the scenes, and more than 60 percent of the dialogue in the finished film. Herman Mankiewicz wrote Citizen Kane.

In Victorville Herman finished the first version of Citizen Kane in twelve weeks. As Houseman chooses to put it, “We were done.” The manuscript was titled American, an ironic jab at Hearst who wrapped himself, like many extremists, in the mantle of Americanism. Despite Houseman’s description of himself and Herman paring every excess out of American, it was 325 pages long and outrageously overwritten, even for a first draft. Houseman blandly ignores this fact. He implies that American, with only the conventional amount of polishing, was what was filmed. Moreover, Houseman departed for New York just four days after delivering American to Welles.

Three months—April 16 to July 16—were required to cut American by half from 325 pages to 156 pages. Herman, too close to the work to be objective and always proprietary about every line, must have found such ruthlessness difficult. One of his later producers, Bert Granet, once said, “Herman would rather talk for three days than change two innocuous lines of dialogue. Before you knew it, Plato, Kant, and Mencken were involved in whether the leading lady should open or shut the door.”

On the other hand, Orson Welles was primed for the job. Houseman, before he left Hollywood, noted that Welles was “working once again with a concentrated, single-minded intensity that I had not seen since the first year of the Mercury.” Welles was attacking ground already broken by Herman, and within American the nucleus of Kane was sound, the surrounding fat clearly visible. Welles, both the producer and director, made all final decisions. Always brilliantly articulate and perceptive, Welles was confident of his ability to write, or rewrite, dialogue. In fact, after Kane, he wrote the screenplays for all but one of the movies he directed—though none were commercially successful or celebrated for their scripts. Most have been judged more or less flawed, often because of Welles’s excesses or irresponsibility. But in 1940 his genius and ego and determination were still in equilibrium.

Moreover, his great gift has always been the leap of his imagination, the exciting boldness of his innovations—augmenting, revising, rearranging, transposing—imprinting his personality on whatever he controlled. He would not have restrained himself in the case of Mankiewicz and American.

Mankiewicz provided Welles with the blueprint of a masterpiece. Then Welles, with solid help from Herman, added important enrichments and refinements and lifted the script the final distance. “I know Orson touched every scene,” says Richard Barr, Welles’s assistant, who later became a Broadway producer and president of the League of New York Theaters. “And I don’t mean cutting a word or two. I mean some serious rewriting, and in a few cases he wrote whole scenes. I think it’s time history balanced this situation.”

For example, Welles remembers writing the confrontation between Kane and a drunk and moralistic Leland: “The truth is, Charlie, you just don’t care about anything except you.” Welles says Thornton Wilder’s Long Christmas Dinner inspired the breakfast scene depicting the deterioration of Kane’s marriage. “Open plagiarism, confessed to at the start,” says Welles delightedly.

But, adds Welles, “I didn’t come in like some more talented writer and save Mankiewicz from disaster.” There was an intermediate script marked “Welles version” and a later one marked “Mankiewicz version.” Revised pages were passed back and forth between the two, Welles changing Herman, who changed Welles—“often much better than mine,” says Welles.

They fought over cuts and additions. Welles wanted the characters talking about Kane to disagree and their versions of the man to be radically different. Herman had softened this approach. Eventually Welles concurred. Herman argued against the farcical quality in the early newspaper scenes— and lost.

In American, Susan Alexander had a young lover at Xanadu who was murdered by the sinister butler, Raymond. Welles insisted that this was too sensational; it would throw the film out of balance. Herman, arguing, said, “But if we keep it in, we’ll never have any trouble with Hearst!”

They disagreed about the scene re-creating Herman’s drunken failure in 1925 to finish his Times review of Insull’s wife. In the scene Jed Leland falls asleep by his typewriter as he annihilates Susan Alexander’s operatic debut. But Welles decided that Kane should finish Leland’s scathing review. Says Welles, “I always wanted Kane to have that sort of almost self-destructive elegance of attitude which, even when it was self-regarding and vain, was peculiarly chic. Mank fought me terribly about that scene: ‘Why should he finish the notice? He wouldn’t. He just wouldn’t print it.’ Which would have been true of Hearst. Oh, how Mank hated my version!”

Herman said about Welles, “It never occurs to him that there is any solution other than his own. Despite yourself, you find yourself accepting this notion.” And indeed, Sara remembers no serious unhappiness over the surgery he and Welles were performing, which is also testimony that Welles never wrote a parallel script. “This was as good a time as Herman had in his career,” she says. “He didn’t drink at all and grew very expansive, was able to enjoy the boys, enjoy Johanna. If Orson had brought in his own script, Herman would have screamed and yelled, ‘Jesus, you should see what he’s got!’ Never.”

Sara had moved the family back to Tower Road, and she has a mental image of meetings in the green-cushioned reed sofa and chairs out near the pool. She remembers clipboards on laps, secretaries, Herman going up to his office to type out a page. Sometimes members of the cast, Mercury actors like Joseph Cotten, joined the sessions. She has movies of barbecues she put on. “We went to Mank’s garden and sat around reading the script and making suggestions,” says Cotten, who played Jed Leland. “What Herman was most concerned about was that we might let Poor Sara know that the man who came by every day was not cleaning the pool. He was a bookie.”

Welles, however, remembers Herman at that time only as an antagonist and rejects the possibility of any such sociable backyard meetings. “There was great work done at this time,” says Welles, “but it wasn’t as happy or useful as it might have been. I have always conceived of Houseman’s main role in Victorville as that of arousing Mank’s latent hatred of anybody who wasn’t a writer—and directing it at me. When Mank left for Victorville, we were friends. When he came back, we were enemies. Mank always needed a villain.”

Orson Welles has his own views on Herman’s contribution to Citizen Kane: “Without Mank it would have been a totally different picture. It suits my self-esteem to think it might have been almost as good, but I could never have arrived at Kane as it was without Herman. When we were together in New York, Mank was absolutely beside himself with delight over the banker Richard Whitney, who was sent to Sing Sing, a perfect J. P. Marquand type. The head of the stock exchange with stripes on. God, how he loved that. And I think Kane was a WASP boogeyman to Mank. A suitable topic for jokes. And Mank’s spleen was given a marvelous direction by that; it gave energy to his writing.

“There is a quality in the film—much more than a vague perfume—that was Mank and that I treasured. It gave a kind of character to the movie which I could never have thought of. It was a kind of controlled, cheerful virulence; we’re finally telling the truth about a great WASP institution. I personally liked Kane, but I went with that. And that probably gave the picture a certain tension, the fact that one of the authors hated Kane and one loved him.

“But in his hatred of Hearst, or whoever Kane was, Mank didn’t have a clear enough image of who the man was. Mank saw him simply as an egomaniac monster with all these people around him. So I don’t think a portrait of a man was ever present in any of Mank’s scripts. Everybody assumes that because Mank was an old newspaperman, and because he wrote about Hearst, and because he was a serious reader on politics, then that is the whole explanation of what he had to do with Kane. I felt his knowledge was journalistic, not very close, the point of view of a newspaperman writing about a newspaper boss he despised.

“I don’t say that Mank didn’t see Kane with clarity. He saw everything with clarity. No matter how odd or how right or how marvelous his point of view was, it was always diamond white. Nothing muzzy. But the truths of the character, Kane, were not what interested him.

“Mank was only interested in very personal terms in the all-devouring egomaniac tycoon. So the easily identifiable, audience identifiable reasons for what happened to Kane were part of Mank’s contribution—and what made the picture finally popular. I think if I had been left to my own devices, we would have had to wait another fifty years.

“My Citizen Kane would have been much more concerned with the interior corruption of Kane. The script is most like me when the central figure on the screen is Kane. And it is most like Mankiewicz when he’s being talked about. And I’m not at all sure that the best part isn’t when they’re talking about Kane. Don’t misunderstand me! I’m not saying I wrote all of one and Mank wrote the other. Mank wrote Kane stuff and I wrote . . . who knows.

“I don’t suppose that authors ever agree on how much they did when they finish. In their secret selves they all think they wrote what they didn’t. I’m sure of that. I’m sure I do. My recollection can be just as. . . .”

There is one postscript to Welles’s remark. Herman, unaware that his attitude toward Hearst would ever be important, answered a 1943 letter from Harold Ross asking for help on a profile on Hearst. Herman answered with his usual dash of self-satire:

I happened to be discussing Our Hero with Orson, and with the fair-mindedness that I have always recognized as my outstanding trait, I said to Orson that, despite this and that, Mr. Hearst was, in many ways, a great man. He was, and is, said Orson, a horse’s ass, no more no less, who had been wrong without exception, on everything he’s ever touched. For instance, for fifty years, said Orson, Hearst did nothing but scream about the Yellow Peril, and then he gave up his seat and hopped off that band wagon two months before Pearl Harbor.

* * *

In July 1940, with the script haggling finished, the two men had another argument over the title. Nobody had been able to think of one. Welles offered a $100 prize to anybody who did. His secretary, Katherine Trosper, came up with one which still moves Welles to delighted laughter. She proposed A Sea of Upturned Faces. It was the RKO studio head, George Schaefer, who suggested Citizen Kane. Herman fought hard against it: “They’ll all think it’s because it’s Cain and Abel that you want to call him Kane.”

“Do you suppose anybody’s ever thought of that?” Welles asks. “How could you? Kane. K. Nice Irish name. With a K. You never fail with a K in a name.”

Then Herman and Welles argued over the casting of Dorothy Comingore as Susan Alexander. At her screen test, Herman told Welles, “Yes, she looks precisely like the image of a kitten we have been looking for.” Welles hired her. Then they learned she was three months pregnant. Herman, worried about physical changes, fought, futilely, to remove her. He finally wrote Welles a letter: “I feel it my duty to express my opinion again —and for the last time, you will be pleased to hear. It is simply incomprehensible to me that with the start of production two weeks off. . . .’’He signed it “Yr obd’t svt.”

The shooting of Citizen Kane began on July 30, 1940. On the twenty-ninth the entire Citizen Kane company—actors, grips, camera crew, the music composer, film cutter, etc.—met for breakfast at 1105 Tower Road. And like the first day of rehearsal for a stage production, the cast read the script aloud from the first to last scene. Welles generously kept Herman and Houseman on the Mercury payroll at $1,000 a week, though both were now largely extraneous. Houseman had had almost no connection with Kane since the delivery of American.

Nobody remembers Herman’s presence on the shooting set, where Welles regarded him as “a visiting enemy.” Herman would refer to Welles as “the boy wonder’s boy wonder” and joked about “Orson’s descent upon Hollywood and his production of the first full-length motion picture completely without film!” At the Campbell Ranch, Herman and Houseman had taken to calling Welles “Maestro, the Dog-Faced Boy,” and once at RKO, nodding toward Welles, Herman remarked, “There but for the grace of God goes God.” Later when Sara bought a dog for Johanna, Herman named it Orson. Perhaps Herman, pouring into Kane his vitriol against all bosses, had to hate Welles, too. Anger was his one completely unstifled passion. “I wonder whether rage wasn’t the best thing Mank had,” says Welles. “But there was nothing secret about Mank’s hate. I think hatred, to be truly useful, had better be partially secretive.”

Herman did see occasional rushes of Kane, but he was not privy to Welles’s cinematic vision which lifted the script beyond anything Hollywood imagined. Herman once vigorously criticized the work in progress. There were not enough standard movie conventions being observed, he said, including too few close-ups. And there was too little “evidence of action,” so Kane was coming out too much like a play.

But Herman was primarily occupied once again by his broken leg. It healed at last. The cast was removed. To celebrate, he went to Chasen’s. He celebrated so thoroughly that when he got up to leave at 2 a.m., his crutch slipped and he fell and broke his leg again. There were more months in a cast in bed—and his left leg remained permanently shorter than his right.

Once the filming of Kane was under way, the question of writer’s credit began to loom. There are two diametrically opposite versions of what happened. One of them has Welles battling to be listed as the sole writer, removing Herman. This version begins in Victorville when Herman mentioned almost casually that it was turning out to be a good script; too bad he wasn’t going to get credit. Rita Alexander felt a rush of indignation: “How could you agree to such a thing?” Herman explained that he needed the money and that this was part of his deal with Welles.

Eventually Herman was assured that he would get cocredit.

But on his return to Tower Road, Sara thought he deserved sole credit. Herman kept blandly telling her not to worry, he would get credit. She must understand that Welles had to get cocredit as part of “written, produced, directed, and performed by Orson Welles.” Anything less would break his contract. “Herman was acquiescent about it, far too acquiescent,” says Sara. “At the time I was not myself. I was Pollyanna. I kept thinking right would win out—which it never does—and that Orson would finally say, ‘Oh, Christ, I’m not going to take any credit; you’ve done it all.’ ”

When Kane was roughly a month into production, Houseman talked to Herman by phone and, says Houseman, “I had to listen to his ambivalent ravings about ‘Monstro,’ his latest name for Welles, whom he alternately described as (one) a genius shooting one of the greatest films ever made, and (two) a scoundrel and a thief, who was now claiming sole credit for the writing of Citizen Kane”

Herman lodged a protest with the Screen Writers Guild. According to Welles’s assistant, Richard Barr, this was a battle Welles set out to win. “I believe,” says Barr, “that Orson didn’t want anybody’s name on that script but his own.” Herman made angry phone calls to influential friends. He asked Sara, “If Welles offers me money to take my name off the credits, should I accept it?” Sara said, “Are you out of your mind?” An offer of $10,000 was actually made, believed Nunnally Johnson, and Hecht advised Herman to “take the money and screw the bastard.”

But then Herman withdrew his guild arbitration request, according to a Welles biographer named Roy Fowler, who did his research in the early 1940’s, when memories were fresh and all the participants alive. Herman was afraid of retribution from Hearst, says Fowler, and decided not to be a writer of record on Kane. Then Herman vacillated. Should he or should he not protest to the guild? In January 1941 Herman was awarded his credit anyway by RKO, says Fowler. The routine guild credit form listed Welles first, Herman second. Somebody—Richard Wilson, his production manager, says Welles did it—circled Mankiewicz with a pencil and drew an arrow putting him in first place. So the official credits read “Screenplay by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles.”

The second version is the Welles story. He regards himself as permanently vilified. “I hate to think,” Welles has said, “what my grandchildren, if I ever have any, are going to think of their ancestor: something rather special in the line of megalomaniac lice.” These are Welles’s facts: “When Mank turned into the real writer, it was immediately understood between us that he would get first billing since he was a distinguished screenwriter. And I’ve always said that his credit was immensely deserved. But then Mankiewicz persuaded himself that he was the sole and only writer. He wanted his name to be the only name. He wanted mine off. I didn’t want mine off. And I tried to persuade Houseman to put his name on, since he’d been working all this time. But Houseman was more interested in mischief than glory. And there wasn’t any way of discussing it with Mank. I felt that some kind of awful magic mirror had been placed between us.”

Welles adds, somewhat plaintively, “Certainly anybody who was around then can . . . maybe Wilson can verify that.” But Richard Wilson does not remember any credit battle at all. The director Peter Bogdanovich, Welles’s friend and defender, wrote for Esquire an elaborate rebuttal to Pauline Kael’s pro-Mankiewicz article in The New Yorker. But he had no evidence supporting Welles’s version of the credit dispute. Welles says that preparing for a possible guild arbitration, he had his secretary assemble all the pages he alone wrote, and copies were sent to Herman. But even Welles himself was unable to extract this memory from the secretary, though she remembers typing many script pages for Welles. “There went my best case,” he bewails.

Screenwriter and director Frank Pierson (Cool Hand Luke, Dog Day Afternoon, A Star Is Born) sits on the guild arbitration committee. It is Pierson’s personal opinion that if Welles wrote original material during the cutting of American, the changes made at that time were more than enough to earn him a second line credit—signifying that Welles was not coauthor but did make significant contributions. Considering the two men involved and the probabilities, the existing credit seems fair.

In the first days of January 1941, a little more than a year after those sessions in the Roxbury bedroom, the filming of Citizen Kane was completed, and almost immediately Louella Parsons precipitated the Hearst counterattack that Herman had feared. The Hollywood of Herman’s era was summed up, in a sense, by the fact that gossip columnists like “Lolly” Parsons, and her prime competitor, Hedda Hopper, wielded serious power.

Originally hired by Hearst because of her friendship with Marion Davies, Louella wrote columns of prattle that were an unimportant mix of cat’s claws and sentimentality. Nothing existed but Hollywood. While Herman had been in Victorville, Europe was moving toward war, and her column reported: “The deadly dullness of the past week was lifted today—when Darryl Zanuck admitted he had bought all rights to Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird for Shirley Temple.” And Hollywood could never decide which was a more frightful punishment—to be banned from Lolly’s column or be the target of her spleen. Furious at Nunnally Johnson, she wrote of his wife: “I ran into Dorris Bowdon last night. She used to be such a pretty girl before she married.”

Tough, fat Louella so worshiped Hearst that when hard-drinking Dr. Harry Martin proposed marriage in 1930—she called him Dockie-Wockie—Hearst had to give his blessings before she would accept. To his endorsement, Hearst later added a wedding present of a $25,000 necklace. And he always made it clear that a quarrel with Louella was a quarrel with the entire Hearst empire.

That was the fight she started after she saw Kane. Herman, in his letter to Alexander Woollcott, told what happened:

Dear Alec:

It is my opinion that Mr. Hearst, who is smart at these things, would have ignored Citizen Kane, positively and negatively, had he been given the chance. But this behavior was denied him chiefly because of an idiot named Louella Parsons and a very smart woman named Hedda Hopper.

The general subject matter of Citizen Kane was a matter of public knowledge for months to everyone connected with the picture industry, except Miss Parsons, its most comprehensive and authoritative reporter. In fact, just a few weeks before the scandal broke, she had called Orson and asked him to confirm or deny, on his sacred word of honor, her exclusive scoop that Citizen Kane was about Communism. Orson denied this.

When, for publicity purposes, Orson assembled the picture and arranged to show it in a very rough form to Life and Look, Hedda forced her way into the showing. At its conclusion, I am told, she got to her feet, screamed magnificently that this constituted an outrage against a great American, and proceeded to call the great American at San Simeon to tell him what she had just seen. (Hedda has for some time been letting it be known that she would be much better in Louella’s job than Louella is, which is true, and it is not impossible that her call was connected with her ambitions.)

Whereupon, Mr. Hearst called Louella and told her about the picture. Louella, every ounce of her suet apoplectic, summoned two Hearst lawyers from downtown Los Angeles, demanded and received an immediate showing of the picture, and at once started telephoning young Bill Hearst, in addition to all the other Hearst executives she could get hold of. She also called George Schaefer, President of RKO, and she told him she would run him out of the business.

An immediate order was issued, banning all Citizen Kane publicity, plus all mention of Welles, myself and others connected with the picture from the Hearst papers. Mr. Hearst himself got in touch with Louis B. Mayer and gave him a calm and unexcited version of the situation as it seemed to him.

To wit: Mr. Hearst had no specific attitude as to whether the picture should be released. He thought this was an attitude the industry should determine. But personally, if he was Mr. Mayer or the Warner Freres, he would be violently opposed to the release, by any company, of a picture that could be considered offensive to anybody, like Mr. Hearst, who had always been such a great friend of the industry. Then Mr. Hearst casually gave them a hundred examples of unfavorable news—rape by executives, drunkenness, miscegenation and allied sports— which on direct appeal from Hollywood he had kept out of his papers in the last fifteen years.

General observations were made—not by Mr. Hearst himself but by high placed Hearst subordinates—that the proportion of Jews in the industry was a bit high and that it might not always be possible to conceal this fact from the American public—with the further fact, which is true, that a number of German Jewish writers, who cannot talk English, have been provided with affidavits and contracts for Hollywood employment at a time when many noble, honest American born writers in Hollywood didn’t know how to pay their rent.

It quickly became difficult, through Mr. Mayer’s efforts, for RKO to get bookings for the picture. The Music Hall in New York, for instance, which had the picture scheduled for release on February 14, found that previous bookings made it impossible to keep that date and that there seemed to be little chance to set a new date for months and months and months to come. Harry Warner, who controls an enormous number of theaters, told RKO he would be delighted to have Citizen Kane play his theaters but that, since there were so many rumors about possible law suits involving many penalties and even jail sentences for local managers, he thought it only a matter of ordinary business precaution to ask RKO to provide him with a $5,000,000.00 indemnity bond. In RKO’s present financial situation, a $50.00 indemnity bond would be funny. The Loew theaters, controlled by M.G.M., were obviously out of the question.

Herman always believed that Hearst knew in advance about Kane and chose not to act. Before shooting started, Herman had given Marion Davies’s nephew, Charlie Lederer, a final version of the script. Concerned about hurting Marion, who had been a generous friend, worried about his future in Hollywood, Herman wanted Lederer’s opinion on her reaction. Lederer remembers thinking, “This book is noteworthy for dullness.” He told Herman not to worry; Susan Alexander bore no resemblance to Marion.

This act of Herman’s was astoundingly ingenuous. Or else he was terrified of success, of creating future expectations he feared he could not satisfy. Lederer, no longer a friend of Herman’s, would have had good reason to take the manuscript to Hearst, who, before production began, could probably have stopped the movie. Lederer, who is noted for his honesty, has always denied showing the script to anybody. But on its return to Herman, pencil lines marked every conceivable reference to Hearst, the tracks, perhaps, of Hearst lawyers.

Also mysterious was a confrontation Herman had at a dinner party soon after Kane was completed and when it was being shown to select audiences in RKO screening rooms. A woman fresh from a week at San Simeon attacked Herman for a sequence in the movie in which a President of the United States is assassinated immediately after inflammatory attacks by Kane’s newspaper, an echo of Hearst’s campaign against President McKinley. This episode, however, was not in the film, had not been in the script Lederer saw, and had occurred only in American.

As the offensive to quash Kane gathered momentum, Nicholas Schenk of Loew’s and MGM told Schaefer at RKO, “Nobody’ll ever see that picture,” and he offered Schaefer the cost of Kane, $800,000, to burn the negative. Louella telephoned Nelson Rockefeller, a major creditor of RKO, which was in receivership, and threatened an ugly story on John D. Rockefeller. She phoned David Sarnoff, president of RCA which controlled RKO, and promised him an unfavorable personal article. The Hearst papers were refusing all RKO advertising, while belaboring Schaefer and Welles. A sycophant to L. B. Mayer, agent Frank Orsatti, circulated the rumor that Schaefer was anti-Semitic. Louella Parsons called the local draft board and demanded to know why Orson Welles, a young man of draft age with no dependents, had not been called into the service. The Hearst chain tried to label Welles a Communist. “It looked like I had a dead duck on my hands,” says Schaefer.

But RKO continued to back Schaefer, and he showed Kane to the chief Time Incorporated libel lawyer, who felt RKO was safe after one minor change was made. Welles’s lawyer, Arnold Weissberger, assured him that in order to sue, “Hearst is going to have to say, the reason I know that SOB is me is because I’m that SOB, which he is not likely to do.”

RKO opened Citizen Kane without repercussions at its Palace Theater on Broadway on May 1, 1941, followed by openings at RKO and rented theaters in other major cities. And publicity programs were printed with photographs of Welles, the one-man band, directing, acting, and writing. “I’m particularly furious at the incredibly insolent description of how Orson wrote his masterpiece,” said Herman in a letter to his father. “The fact is that there isn’t one single line in the picture that wasn’t in writing—writing from and by me—before ever a camera turned.”

Now that Hearst had failed to take action, Schaefer threatened an antitrust suit against Warner Brothers, which relented, followed rapidly by the Paramount chain and Loew’s. But though Kane, made by Welles for the extraordinarily small sum of $746,000 did not lose money, it was too unorthodox for the forties audiences and was a commercial failure.

Nevertheless, few motion pictures ever received reviews equaling Kane‘s. Howard Barnes, in the New York Herald Tribune, opened his with the sentence “The motion picture stretched its muscles at the Palace Theater last night to remind one that it is the sleeping giant of the arts.” The New York World-Telegram announced that “Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane is a Masterpiece of the Cinema.” PM called it “A Truly Great Picture.” Archer Winsten, in the New York Post, called the film “a great work of art” and said, “Citizen Kane will be a film which is important in the history of American motion pictures,” while the Hollywood Reporter trumpeted: “Mr. Genius Comes Through; ‘Kane’ Astonishing Picture.”

Only one critic, Eileen Creelman in the New York Sun, called Kane “a cold picture” and echoed Welles’s own misgivings. “Its faults live with me,” says Welles, who considers his 1966 Chimes at Midnight by far his best film. “Kane was made in the most wildly fun-and-games kind of way. But from the very beginning I felt it had a curious iciness at its heart. It has moments when the whole picture seems to me to echo a bit. I was always conscious of the sound of footsteps echoing in some funny way—a certain effect made by proportions of certain chemicals. And that spirit was very strange. Very strange. It disturbed me and still does.”

Following the reviews, Welles wired Herman:

Dear Mankie. If you haven’t seen all the papers I’ll be glad to send them on. In the meantime feel you should know that a lady named Miss Closer has been phoning me claiming to be your rosebud. She says she has written her own libretto and some day you will have to hear her sing. She tells me to tell you this. Please advise. Love—Orson.

Herman’s answer was from Sara.: “Report to me, the only original authentic rosebud, on all of Herman’s rosebuds you meet giving full details including what kind of spectacles, how many pimples, and so forth. Isn’t it wonderful about the picture? Love, Sara.”

Citizen Kane was nominated for an Academy Award in every possible category, including Best Original Screenplay. Herman insisted he had no chance to win, though the Hollywood Reporter had given the film first place in ten of its twelve divisions. The fear of Hearst, he felt, was still alive. And Hollywood’s resentment and distrust of Welles, the nonconformist upstart, were even greater since he had lived up to his wonderboy ballyhoo. The Academy Awards dinner, broadcast on radio, was held in February 1942. Welles was in South America filming Carnival. Herman refused to attend. “He did not want to be humiliated,” says Sara. “He thought he’d get mad and do something drastic when he didn’t win.”

The night of the awards Herman turned on his radio and sat in his bedroom chair. Sara lay on his bed. As the screenplay category approached, he pretended to be hardly listening. Suddenly from the radio, half screamed, came “Herman J. Mankiewicz.” Welles’s name as coauthor was drowned out by voices all through the audience calling out, “Mank! Mank! Where is he?” And audible above all others was Irene Selznick: “Where is he?”

Herman was in his bathrobe and slippers doing a dance with Sara, stumping around on his bad leg. Olga Aaronson was at Mattie’s house, and still in their nightgowns, the two women drove right over. And Olga, holding up the long skirt of her gown, danced with Herman.

George Schaefer accepted Herman’s Oscar. Except for this coauthor award, the Motion Picture Academy excommunicated Orson Welles. John Ford was best director for How Green Was My Valley. Gary Cooper won for Sergeant York. The Best Picture was How Green Was My Valley. But as Pauline Kael put it, “The members of the Academy . . . probably felt good because their hearts had gone out to crazy, reckless Mank, their own resident loser-genius.” When his Oscar was sent over by George Schaefer with “congratulations and best wishes from a high-priced office boy,” Herman was unashamedly proud of it. He put it on his bureau in his bedroom, then said to Sara, “Would you like to take it down to the living room?”

For a birthday present Johanna painted a crude Oscar on a blue tie—and Herman wore it everywhere. He figured out the acceptance speech he should have made if he had been at the Academy Awards dinner: “I am very happy to accept this award in Mr. Welles’s absence because the script was written in Mr. Welles’s absence.”

A small patter of congratulatory wires came in from B. P. Schulberg, from Moss Hart (“I am proud to know you”), Herbert Bayard Swope (“I hope it means money in your pocket”). Herman sent out answers, joking that it had been a sympathy vote: “I am frankly pleased to have won the award, but I don’t look forward to much more success in this direction, because the right leg won’t stand any more breaking, and that leaves only one leg left.”

“But,” says Sara, “I think Herman was a little disappointed at both Ben and Rose Hecht’s reception of Citizen Kane. They never said anything about it.”

From Rio de Janeiro, Orson Welles wrote:

Dear Mankie:

Here’s what I wanted to wire you after the Academy Dinner: “You can kiss my half.”

I dare to send it through the mails only now that I find it possible to enclose a ready-made retort. I don’t presume to write your jokes for you, but you ought to like this:

“Dear Orson: You don’t know your half from a whole in the ground.”

Affectionately.

“God, if I hadn’t loved him,” says Welles, “I would have hated him after all those ridiculous stories, persuading people I was offering him money to have his name taken off. . . . That was the kind of thing he enjoyed for mischievous purposes, moving aside from the facts if it would make a little fuss and entertain everybody. He was not wedded to the truth. And I swear to you, we used to sit around and laugh and say, ‘There goes Mank.’ Wouldn’t you know that having succeeded in . . . here we had a fine movie . . . that he would be carrying on like this, denouncing me as a coauthor, screaming around. You know, he just couldn’t relax. Imagine a man who could command not friendship; you felt an emotion for him that’s different from friendship to such a point that even I, feeling as I did, never for a moment felt the slightest change in my affection for him. You felt this fondness, though you knew that if he had a chance, he would cut you off at the knees. Not because he would dance on your grave, but because he wanted company down there himself!”