Notes on the Nihilist Poetry of Sam Peckinpah

by Pauline Kael

Sam Peckinpah is a great “personal” filmmaker; he’s an artist who can work as an artist only on his own terms. When he does a job for hire, he must transform the script and make it his own or it turns into convictionless self-parody (like The Getaway). Peckinpah likes to say that he’s a good whore who goes where he’s kicked. The truth is he’s a very bad whore: he can’t turn out a routine piece of craftsmanship—he can’t use his skills to improve somebody else’s conception. That’s why he has always had trouble. And trouble, plus that most difficult to define of all gifts—a film sense—is the basis of his legend.

Most movie directors have short wings; few of them are driven to realize their own vision. But Peckinpah’s vision has become so scabrous, theatrical, and obsessive that it is now controlling him. His new film, The Killer Elite, is set so far inside his fantasy-morality world that it goes beyond personal filmmaking into private filmmaking. The story, which is about killers employed by a company with C.I.A. connections, is used as a mere framework for a compressed, almost abstract fantasy on the subject of selling yourself yet trying to hang on to a piece of yourself. Peckinpah turned fifty while he was preparing this picture, and, what with booze, illness, and a mean, self-destructive streak, in recent years he has looked as if his body were giving out. This picture is about survival.

There are so many elisions in The Killer Elite that it hardly exists on a narrative level, but its poetic vision is all of a piece. Unlike Peckinpah’s earlier, spacious movies, with Lucien Ballard’s light-blue, open-air vistas, this film is intensely, claustrophobically exciting, with combat scenes of martial-arts teams photographed in slow motion and then edited in such brief cuts that the fighting is nightmarishly concentrated—almost subliminal. Shot by Phil Lathrop in cold, five-o’clock-shadow green-blue tones, the film is airless—an involuted, corkscrew vision of a tight, modern world. In its obsessiveness, with the links between sequences a matter of irrational, poetic connections, The Killer Elite is closer to The Blood of a Poet than it is to a conventional thriller made on the C.I.A.-assassins subject, such as Three Days of the Condor. And, despite the script by Marc Norman and Stirling Silliphant that United Artists paid for, the film isn’t about C.I.A.-sponsored assassinations—it’s about the blood of a poet.

With his long history of butchered films and films released without publicity, of being fired and blacklisted for insubordination, of getting ornerier and ornerier, Peckinpah has lost a lot of blood. Even The Wild Bunch, a great imagist epic in which Peckinpah, by a supreme burst of filmmaking energy, was able to convert chaotic romanticism into exaltation—a film comparable in scale and sheer poetic force to Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai—was cut in its American release, and has not yet been restored. And Peckinpah was forced to trim The Killer Elite to change its R rating to a PG. Why would anybody want a PG-rated Peckinpah film? The answer is that United Artists, having no confidence in the picture, grabbed the chance to place it in four hundred and thirty-five theatres for the Christmas trade; many of those theatres wouldn’t have taken it if it had an R and the kids couldn’t go by themselves. The film was flung into those neighborhood houses for a quick profit, without benefit of advance press screenings or the ad campaign that goes with a first-run showing. Peckinpah’s career is becoming a dirty, bitter game of I-dump-on-you-because-you-dump-on-me. Increasingly, his films have reflected his war with the producers and distributors, and in The Killer Elite this war takes its most single-minded form.

Peckinpah’s roots are in the theatre as much as they’re in the West; he loves the theatricality of Tennessee Williams (early on, he directed three different stage productions of The Glass Menagerie), and, personally, he has the soft-spoken grandness of a Southerner in a string tie—when he talks of the way California used to be, it is in the reverent tone that Southerners use for the Old South. The hokum runs thick in him, and his years of television work—writing dozens of “Gunsmoke” episodes, “creating” the two series “The Rifleman” and “The Westerner”—pushed his thinking into good-guys-versus-bad-guys formats. The tenderness he felt for Tennessee Williams’ emotional poetry he could also feel for a line of dialogue that defined a Westerner’s plain principles. He loves actors, and he enjoyed the TV-Western make-believe, but that moment when the routine Western script gave way to a memorably “honest” emotion became for him what it was all about. When Peckinpah reminisces about “a great Western,” it sometimes comes down to one flourish that for him “said everything.” And Peckinpah lives by and for heroic flourishes; they’re his idea of the real thing, and in his movies he has invested them with such nostalgic passion that a viewer can be torn between emotional assent and utter confusion as to what, exactly, he’s assenting to.

As the losing battles with the moneymen have gone on, year after year, Peckinpah has—only partly sardonically, I think—begun to see the world in terms of the bad guys (the studio executives who have betrayed him or chickened out on him) and the people he likes (generally actors), who are the ones smart enough to see what the process is all about, the ones who haven’t betrayed him yet. Hatred of the bad guys—the total mercenaries—has become practically the only sustaining emotion in his work, and his movies have become fables about striking back.

Many of the things that Peckinpah says in conversation began to seep into his last film, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), turning it into a time-machine foul-up, with modern, airborne killers functioning in the romanticized Mexico of an earlier movie era. Essentially the same assassins dominate the stylized, darkened San Francisco of The Killer Elite. In a Playboy interview with William Murray in 1972, Peckinpah was referring to movie producers when he said, “The woods are full of killers, all sizes, all colors. … A director has to deal with a whole world absolutely teeming with mediocrities, jackals, hangers-on, and just plain killers. The attrition is terrific. It can kill you. The saying is that they can kill you but not eat you. That’s nonsense. I’ve had them eating on me while I was still walking around.” Sam Peckinpah looks and behaves as if he were never free of their gnawing. He carries it with him, fantasizes it, provokes it, makes it true again and again. He romanticizes himself as one of the walking wounded, which is no doubt among the reasons he wanted to direct Play It As It Lays. (He was rejected by the businessmen as being strictly an action director.) In that Murray interview, he was referring to the making of movies when he said, “When you’re dealing in millions, you’re dealing with people at their meanest. Christ, a showdown in the old West is nothing compared with the infighting that goes on over money.’’

Peckinpah swallowed Robert Ardrey whole; it suited his emotional needs—he wants to believe that all men are whores and killers. He was talking to Murray about what the bosses had done to him and to his films when he said, “There are people all over the place, dozens of them, I’d like to kill, quite literally kill.” He’s dramatizing, but I’ve known Sam Peckinpah for over ten years (and, for all his ceremonial exhibitionism, his power plays, and his baloney, or maybe because of them, there is a total, physical elation in his work and in his own relation to it that makes me feel closer to him than I do to any other director except Jean Renoir) and I’m convinced that he actually feels that demonic hatred. I think Sam Peckinpah feels everything that he dramatizes—he allows himself to. He’s a ham: he doesn’t feel what he doesn’t dramatize..

Peckinpah has been simplifying and falsifying his own terrors as an artist by putting them into melodramatic formulas. He’s a major artist who has worked so long in penny-dreadful forms that when he is finally in a position where he’s famous enough to fight for his freedom—and maybe win—he can’t free himself from the fear of working outside those forms, or from the festering desire for revenge. He is the killer-61ite hero played by James Caan in this hallucinatory thriller, in which the hirelings turn against their employers. James Caan’s Mike, a No. 1 professional, is mutilated by his closest friend, George Hansen (Robert Duvall), at the order of Cap Collis (Arthur Hill), a defector within the company—Communications Integrity Associates—that they all work for. Mike rehabilitates himself, however, by a long, painful struggle, regaining the use of his body so that he can revenge himself. He comes back more determined than ever, and his enemies—Hansen and Cap Collis—are both shot. But when the wearily cynical top man in the company (Gig Young) offers Mike a regional directorship—Cap Collis’s newly vacated position—he rejects it. Instead, he sails—literally—into unknown seas with his loyal friend the gunman-mechanic Mac (Burt Young).

There’s no way to make sense of what has been going on in Peckinpah’s recent films if one looks only at their surface stories. Whether consciously or, as I think, part unconsciously, he’s been destroying the surface content. In this new film, there aren’t any of the ordinary kinds of introductions to the characters, and the events aren’t prepared for. The political purposes of the double-crosses are shrouded in a dark fog, and the company itself makes no economic sense. There are remnants of a plot involving a political leader from Taiwan (he sounds off about democratic principles in the manner of Paul Henreid’s Victor Laszlo in Casablanca), but that fog covers all the specific plot points. Peckinpah can explain this disintegration to himself in terms of how contemptible the material actually is—the fragmented story indicates how he feels about what the bosses buy and what they degrade him with. He agrees to do these properties, to be “a good whore,” and then he can’t help turning them into revenge fantasies. His whole way of making movies has become a revenge fantasy: he screws the bosses, he screws the picture, he screws himself.

The physical rehabilitation of the hero in The Killer Elite (his refusal to accept the company’s decision that he’s finished) is an almost childishly transparent disguise for Peckinpah’s own determination to show Hollywood that he’s not dead yet—that, despite the tabloid views of him, frail and falling-down drunk, he’s got the will to make great movies. He’s trying to pick up the pieces of his career. Amazingly, Peckinpah does rehabilitate himself; his technique here is dazzling. In the moments just before violence explodes, Peckinpah’s work is at its most subtly theatrical: he savors the feeling of power as he ticks off the seconds before the suppressed rage will take form. When it does, it’s often voluptuously horrifying (and that is what has given Peckinpah a dubious reputation—what has made him Bloody Sam), but this time it isn’t gory and yet it’s more daring than ever. He has never before made the violence itself so surreally, fluidly abstract; several sequences are edited with a magical speed—a new refinement. In Alfredo Garcia, the director seemed to have run out of energy after a virtuoso opening, and there was a scene, when the two leads (Warren Oates and Isela Vega) were sitting by the side of a road, that was so scrappily patched together, with closeups that didn’t match, that Peckinpah appeared to have run out of zest for filmmaking. Maybe it was just that in Alfredo Garcia his old obsessions had lost their urgency and his new one—his metaphoric view of modern corporate business, represented by the dapper, errand-boy killers (Gig Young and Robert Webber as mirror-image lovers)—had thrown him off balance. He didn’t seem to know why he was making the movie, and Warren Oates, who has fine shadings in character roles, was colorless in the central role (as he was also in the title role of John Milius’s Dillinger). Oates is a man who’s used to not being noticed, and his body shows it. When he tried to be a star by taking over Peckinpah’s glasses and mustache and manner, he was imitating the outside of a dangerous person—the inside was still meek. And, of course, Peckinpah, with his feelers (he’s a man who gives the impression of never missing anything going on in a room), knew the truth: that the actor in Alfredo Garcia who was like him, without trying at all, was Gig Young, with his weary pale eyes. In The Killer Elite, James Caan is the hero who acts out Peckinpah’s dream of salvation, but it’s Gig Young’s face that haunts the film. Gig Young represents Peckinpah’s idea of what he will become if he doesn’t screw them all and sail away.

Peckinpah is surely one of the most histrionic men who have ever lived: his movies (and his life, by now) are all gesture. He thinks like an actor, in terms of the effect, and the special bits he responds to in Westerns are actors’ gestures—corniness transcended by the hint of nobility in the actors themselves. Like Gig Young, he has the face of a ravaged juvenile, a face that magnetizes because of the suggestion that the person understands more than he wants to. It’s a fake, this look, but Peckinpah cultivates the whore-of-whores pose. He plays with the idea of being the best of men and, when inevitably betrayed, the worst of men. (He’s got to be both the best and the worst.) Gig Young has the same air of gentleness that Peckinpah has, and the dissolute quality of an actor whose talents have been wasted. Gig Young’s face seems large for his body now, in a way that suggests that it has carried a lot of makeup in its time; he looks rubbery-faced, like an old song-and-dance man. Joel McCrea, with his humane strength, may have been Peckinpah’s idealized hero in Ride the High Country, and William Holden may have represented a real man to him in The Wild Bunch, but Gig Young, who represents what taking orders from the bosses—being used—does to a man of feeling, is the one Peckinpah shows the most affection for now. Gig Young can play the top whore in The Killer Elite because his sad eyes suggest that he has no expectations and no illusions left about anything. And Peckinpah can identify with this character because of the element of pain in Gig Young, who seems to be the most naked of actors—an actor with nowhere to hide. (Peckinpah’s own eyes are saintly-sly, and he’s actually the most devious of men.) Peckinpah could never for an instant identify with the faceless corporate killer played by Arthur Hill. When you see Arthur Hill as Cap Collis, the sellout, you know that it didn’t cost Collis anything to sell out. He’s a gutless wonder, something that crawled out of the woodwork. Arthur Hill’s unremarkable, company-man face and lean, tall body are already abstractions; he’s a corporate entity in himself. In Peckinpah’s iconography, he’s a walking cipher, a man who wasn’t born of woman but was cast in a mold—a man whose existence is a defeat for men of feeling.

James Caan goes through the athletic motions of heroism and acts intelligently, but he doesn’t bring the right presence to the role. His stoicism lacks homicidal undercurrents, and he doesn’t have the raw-nerved awareness that seems needed. The face that suggests some of what Peckinpah is trying to express—the residual humanity in killers—is that of Burt Young, as the devoted Mac. The swarthy, solid, yet sensitive face of Burt Young (he played the man looking at pictures of his faithless wife at the beginning of Chinatown) shows the weight of feelings. Mac’s warm, gravelly croak and his almost grotesque simpleness link him to the members of the Wild Bunch. His is a face with substance, capable of dread on a friend’s account. In The Killer Elite, his is the face that shows the feelings that have been burnt out of Gig Young’s.

Peckinpah has become wryly sentimental about his own cynicism. When the Taiwanese leader’s young daughter pompously tells the hero that she’s a virgin, and he does a variation on Rhett Butler, saying, “To tell you the truth, I really don’t give a shit,” the director’s contempt for innocence is too self-conscious, and it sticks out. Peckinpah wants to be honored for the punishment he’s taken, as if it were battle scars. The doctor who patches up the hero says, “The scar looks beautiful”—which, in context, is a sleek joke. But when the hero’s braced leg fails him and he falls helplessly on his face on a restaurant floor, Sam Peckinpah may be pushing for sympathy for his own travail. From the outside, it’s clear that even his battle scars aren’t all honorable—that a lot of the time he wasn’t fighting to protect his vision, he was fighting for tortuous reasons. He doesn’t start a picture with a vision; he starts a picture as a job and then perversely—in spite of his deal to sell out—he turns into an artist.

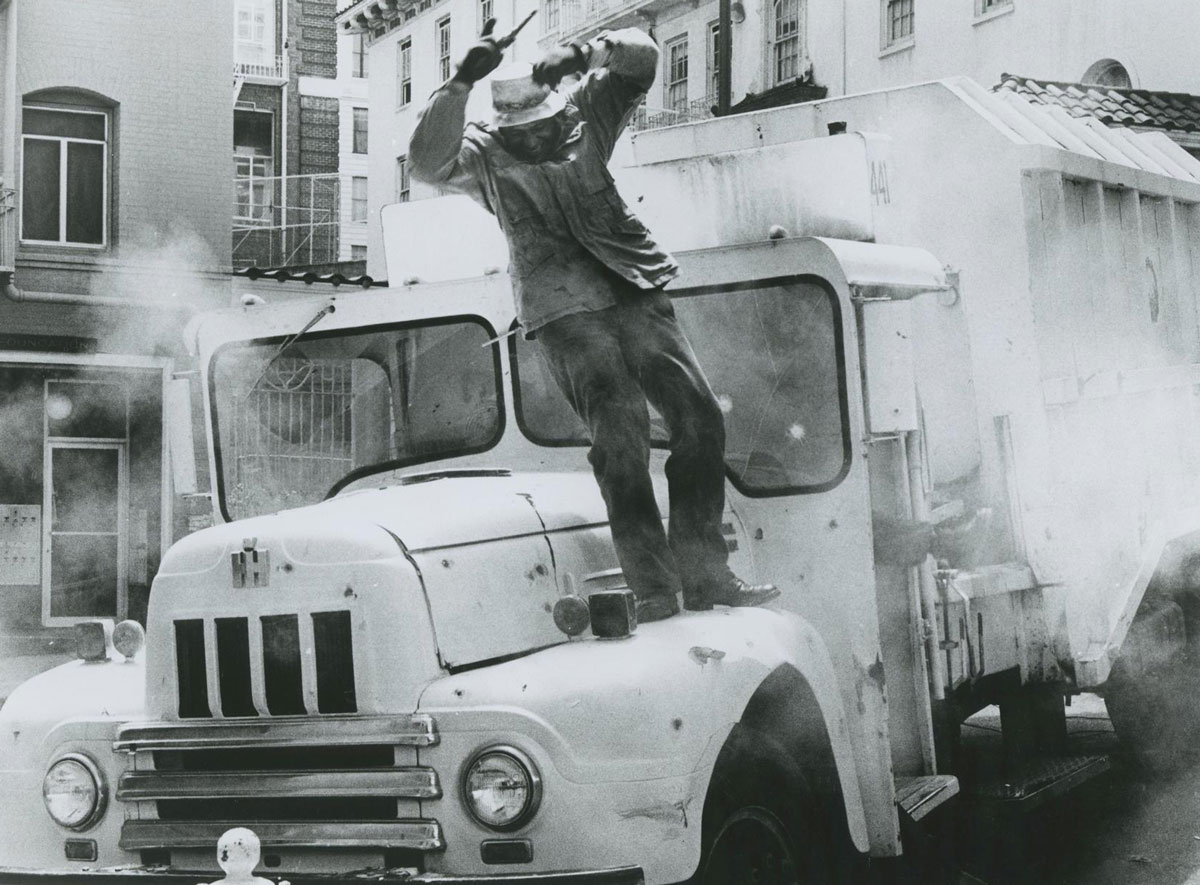

Much of what Peckinpah is trying to express in The Killer Elite is probably inaccessible to audiences, his moral judgments being based less on what his characters do than on what they wouldn’t stoop to do. (In Hollywood, people take more pride in what they’ve said no to than in what they’ve done.) Yet by going so far into his own hostile, edgily funny myth—in being the maimed victim who rises to smite his enemies—he found a ferocious unity, an Old Testament righteousness that connects with the audience in ways his last few pictures didn’t. At the beginning of The Killer Elite, the lack of sunlight is repellent; the lividness looks cheap and pulpy—were those four hundred and thirty-five prints processed in a sewer? But by the end a viewer stares fixedly, not quite believing he’s seeing what he’s seeing: a nightmare ballet. In the free-form murderous finale, with guns, Samurai swords, and lethal skills one has never heard of before, there are troops of Oriental assassins scurrying over the phantom fleet of Second World War ships maintained in Suisun Bay, north of San Francisco. Wrapped up in their cult garb so we can’t tell one from another, the darting killers, seen in those slow-motion fast cuts, are exactly like Peckinpah’s descriptions of the teeming mediocrities, jackals, hangers-on, and just plain killers that Hollywood is full of.

The film is so cleanly made that Peckinpah may have wrapped up this obsession. When James Caan and Burt Young sail away at the end, it’s Sam Peckinpah turning his back on Hollywood. He has gone to Europe, with commitments that will keep him there for at least two years. It would be too simple to say that he has been driven out of the American movie industry, but it’s more than half true. No one is Peckinpah’s master as a director of individual sequences; no one else gets such beauty out of movement and hard grain and silence. He doesn’t do the expected, and so, scene by scene, he creates his own actor-director’s suspense. The images in The Killer Elite are charged, and you have the feeling that not one is wasted. What they all add up to is something else—but one could say the same of The Pisan Cantos. Peckinpah has become so nihilistic that filmmaking itself seems to be the only thing he believes in. He’s crowing in The Killer Elite, saying, “No matter what you do to me, look at the way I can make a movie.” The bedevilled bastard’s got a right to crow.

The New Yorker, January 12, 1976