INTRODUCTION

Heart of Darkness, first published in 1899, is one of the most potent texts of the twentieth century. This short work, hardly long enough to be called a novel, has produced a vast array of readings and has recently provoked intense controversy. But whether hailed as a masterpiece, or reviled as racist and sexist, it seems impossible to ignore. Its title and themes are likely to be invoked in discussions of the human condition, of good and evil, and of imperialism and its consequences; in any gathering of readers, or company of critics, it is likely to disturb and compel. This Guide aims to trace the critical history of Heart of Darkness from the first reviews to the latest readings, and to select, from the huge range of available material, the most perceptive and relevant interpretations and evaluations. In this Introduction, Heart of Darkness is set in the context of Conrad’s life, and the criticism on which the Guide will focus is outlined.

It is useful to start by recalling Conrad’s original name: Józef Teodor Konrad Nałęcz-Korzeniowski. To do so is to highlight the otherness of this writer who identified himself so closely with England but who remained, in crucial respects, forever different. The boy who was later to become Joseph Conrad was born in 1857 at Berdyczów, in what is now the Ukraine; his father, Apollo, a romantic nationalist ardently opposed to Russian domination, was also a poet, playwright and translator. The Korzeniowskis moved to Warsaw in 1861, where a national resistance movement was centred, but Apollo’s political activities soon led to his arrest and to his exile, with his wife and small son, to Vologda in northeast Russia. In 1863, the family were allowed to move to Cherikhov, but Conrad’s mother died in 1865, when he was seven. Apollo, bitter and depressed, his lungs racked by consumption, was allowed to return from exile in 1867, and settled with his son at Lvov. The boy went to preparatory school, started to write plays, and read avidly. But his father was dying. Conrad later recalled the importance of reading as a refuge at this time: T don’t know what would have become of me if I had not been a reading boy’.1 In February 1 869, father and son moved to Krakow, and on 23 May of that year Apollo died.

The young Jozef, aged eleven, was then looked after by Thaddeus Bobrowski, his wealthy uncle. In 1874, Thaddeus allowed his nephew, who had reached the age of sixteen, to fulfil a wish that had been developing for some time and become a sailor. He went to France to join the French merchant marine, and in 1875 sailed for the West Indies. But his personal and working life were unhappy; he fell heavily into debt; and in February 1878, he tried to kill himself. He had a miraculous escape; the bullet passed through his body but missed his heart. After this close encounter with death, he resolved to start a new life.

The first stage of this new life would be as a sailor in the British Merchant Navy; and here Conrad would have some success. He passed examinations to become a second mate in 1880, a first mate in 1884, and finally, in 1886, a Master. In that year, he also became a naturalised British subject, and apparently wrote his first short story, ‘The Black Mate’, before going on to begin a novel, Almayer’s Folly, in 1889. But until that novel was published six years later, he was still, to all outward appearances, more seaman than writer. His voyages between December 1874 and January 1894 took him around the globe, to Sydney, Singapore, Bombay, the East Indies — and, very significantly for Heart of Darkness, to Africa.

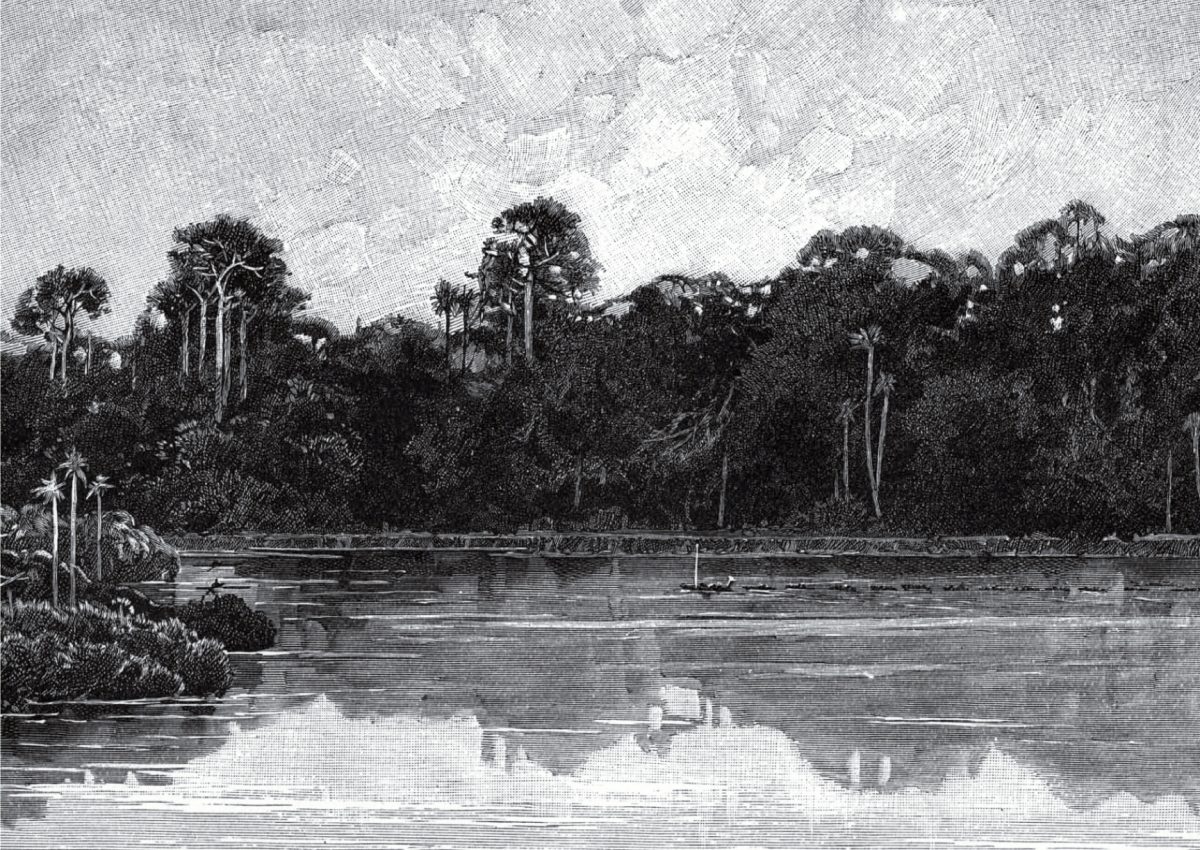

By his own account, in the essay ‘Geography and Some Explorers’, Africa had long fascinated Conrad. Addicted as a boy to ‘map-gazing’,2 he had aroused the derision of his schoolmates one day by ‘putting [his] finger on a spot in the very middle of the then white heart of Africa’ and declaring that ‘some day I would go there’.3 In 1890, at a time when Africa was the subject of intense newspaper interest because of Henry Morton Stanley’s successful quest for Livingstone, Conrad at last made good his schoolboy boast, securing a post as steamboat captain with the company responsible for trading in the Belgian Congo. The boat to which he had been appointed was to take an exploring expedition, led by Alexandre Delcommune, from Kinshasa to Katanga. On 12 June 1890, Conrad landed in the Congo at Boma, moved on to Matadi, and then, on 28 June, set off on the 230-mile trek to Kinshasa, making brief entries in a diary as he travelled. The journey usually took about seventeen days, but Conrad’s lasted thirty-five. This delay displeased the manager of the Kinshasa station, Camille Delcommune, the brother of the leader of the proposed Katanga expedition; he received Conrad coldly, and the feeling was mutual. In a letter to an aunt, Conrad called Delcommune ‘a common ivory-dealer with base instincts’.4 The boat Conrad had hoped to command was damaged, but on 13 August he and Camille Delcommune set off on the 1,000 mile journey up the Congo to Stanley Falls in what Conrad later recalled as ‘a wretched little stern-wheel steamboat’, the Roi des Beiges (King of the Belgians); Conrad, as he himself put it, ‘went as a supernumerary on board … in order to learn about the river’.5

In ‘Geography and Some Explorers’, he evokes a moment that sums up his complex feelings on at last reaching Stanley Falls. Alone on the deck of the steamer, ‘smoking the pipe of peace after an anxious day’ and with the ‘subdued thundering mutter’ of the Falls hanging ‘in the heavy night air’, he says to himself ‘with awe, “This is the very spot of my boyish boast'”. But a ‘great melancholy’ then falls on him at the contrast between ‘the idealized realities of a boy’s daydreams’ and ‘the unholy recollection of a prosaic newspaper “stunt”‘ — Stanley’s quest for Livingstone — and ‘the distasteful knowledge of the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of the human conscience and geographical exploration’ — the European exploitation of the Belgian Congo.6 ft is this painful contradiction between dream and reality that seems to have formed the basis of ‘Heart of Darkness’.

When the captain of the Roi des Beiges steamer fell ill, Conrad took command for part of the journey back to Kinshasa. But he himself had suffered from fever and dysentery during the voyage, and after arriving in Kinshasa on 24 September, he acknowledged that he felt ‘somewhat weak physically and not a little demoralized’.7 He had no ship to command, and he could see no chance of promotion or a higher salary while Camille Delcommune was manager. Soon he was seriously ill. Much to his relief, the company released him from his three-year contract, and he returned to England in January 1891, going into hospital in London and then convalescing at Champel near Geneva. His attempt to fulfil his boyhood dream had been a painful, disillusioning experience.

It would be some years, however, before that experience fed into Heart of Darkness. In the meantime, Conrad made the transition from seaman to writer, and from bachelor to husband. Almayer’s Folly appeared in 1895, and he married Jessie George in March 1896. In the same year, An Outcast of the Islands came out, and The N i g g e r of the ‘Narcissus’ was published in 1897. It was also in 1897 that he began to write for Blackwood’s Magazine, where the first version of Heart of Darkness — or ‘The Heart of Darkness’, as it was initially called — would appear, in instalments, in 1899.

On 30 December 1898, William Blackwood, the magazine’s proprietor and editor, had written to Conrad asking for a contribution for the February issue, which would be the thousandth number. Conrad quickly replied that he was already working on a story that was well advanced and should be finished in a few days. He called it ‘a narrative after the manner of youth [sic] told by the same man [Marlow] dealing with his experiences on a river in Central Africa’; but he expressed reservations as to its suitability for the issue Blackwood had in mind. Affirming that he had ‘no doubts as to the workmanship’, he said that the ‘idea in it is not as obvious as in youth — or at least not so obviously presented’ and that he did not ‘know whether the subject will commend itself to you for that particular number’.8 He then went on:

The title I am thinking of is ‘The Heart of Darkness’ but the narrative is not gloomy. The criminality of inefficiency and pure selfishness when tackling the civilizing work in Africa is a justifiable idea. The subject is of our time distinctly — though not topically treated. It is a story as much as my Outpost of Progress was but, so to speak, ‘takes in’ more — is a little wider — is less concentrated upon individuals.9

Despite Conrad’s doubts, the first part of Heart of Darkness did appear in the thousandth issue of Blackwood’s Magazine. Conrad found, as he went on with the story, that it expanded beyond his original conception — ‘ft]he thing has grown on me’10 — and he continued to feel it might present difficulties of interpretation. Writing to his friend R. B. Cunninghame Graham on 8 February 1899, he avowed himself ‘in the seventh heaven’ because Graham liked the story so far; but he also warned of two more instalments to come ‘in which the idea is so wrapped up in secondary notions that You — even You! — may miss it’.11 He went on to tell Graham that ‘[y]ou must remember that I don’t start with an abstract notion. I start with definite images and as their rendering is true some little effect is produced’,12 and then reiterated his apprehension about Graham’s response to the forthcoming episodes, saying that ‘[s]o far the note struck chimes in with your convictions — mais apres [but after?]? There is an apres’. He thought, however, that if Graham looked ‘a little into the episodes you will find in them the right intention though I fear nothing that is practically effective’.13

Conrad completed the tale, though telling John Galsworthy that the ‘finishing of fit] took a lot out of me’.14 Three years later, towards the end of 1902, Blackwood brought out a volume in which ‘Youth’, the title story, was accompanied by ‘The End of the Tether’ and by Heart of Darkness. Earlier that year, Conrad had looked back on ‘Heart of Darkness’, along with ‘Youth’, as ‘a thing intimately felt’15 and had stressed its seriousness and substance. Writing to his French translator, H-D. Davray, on 10 April 1902, he called it ‘a wild story of a journalist who becomes manager of a station in the interior and makes himself worshipped by a tribe of savages’, and said ‘[t]hus described, the subject seems comic, but it isn’t’.16 In a letter to Blackwood himself on 31 May 1902, he spoke of his method as one in which ‘the final incident’ of a story functioned to make ‘the whole story in all its descriptive detail . . . fall into place fand] acquire its value and significance’, and he cited Heart of Darkness as one example of this method:

[In] the last pages of [‘Heart of Darkness’] the interview of the man and girl locks in — as it were — the whole 30000 words of narrative description into one suggestive view of a whole phase of life and makes of that story something quite on another plane than an anecdote of a man who went mad in the Centre of Africa.17

Conrad’s claim that Heart of Darkness was ‘quite on another plane than an anecdote of a man who went mad in the Centre of Africa’ would be amply substantiated by twentieth-century critics. The first chapter of this Guide traces its critical reception from its first publication in book form in 1902 to the end of the 1950s. Even when it first appeared in book form, in the volume of which ‘Youth’ was the title story, certain reviewers, such as Edward Garnett and Hugh Clifford, sensed its importance, as we shall see. If Heart of Darkness was then to be overshadowed by Conrad’s longer fictions during the rest of his life, a sign of its imminent importance for the mid-twentieth century appeared in 1925, the year after his death, when T. S. Eliot used it as the epigraph to his poem ‘The Hollow Men’, a poem which quickly came to be seen as a classic modern expression of futility and despair. Heart of Darkness suffered in the general posthumous decline in Conrad’s reputation, but by the late 1930s a revival was under way, which resulted in the early 1940s in positive evaluations of Conrad by two leading Cambridge critics, M.C. Bradbrook and F. R. Leavis. Both of these praised Heart of Darkness highly, although Leavis also mounted an influential critique of what he saw as Conrad’s excessive use of abstract adjectives such as ‘implacable’ and ‘inscrutable’. After the pioneering work of Bradbrook and Leavis, the next decade, the 1950s, was to see key interpretations of Heart of Darkness by Raymond Williams, Thomas Moser, and, above all, Albert J. Guerard, all of which are discussed in the first chapter of this Guide.

In the 1960s Heart of Darkness reached the height of its reputation, and the second chapter of this Guide looks at major readings by Lionel Trilling, who sees it as the quintessential modern text, Eloise Knapp Hay, who focuses on what she regards as its critique of imperialism, J. Hillis Miller, who analyses it as a potentially transformative recognition of nihilism, and Stanton de Voren Hoffman, who homes in on its humour and relates that relatively neglected aspect of Conrad’s novel to its major themes.

The third chapter moves on to the 1970s, when the apparent consolidation of the novel’s reputation — represented in this Guide by C. B. Cox’s account — was shattered by Chinua Achebe’s attack on the novel as racist. If Achebe’s attack represented the challenge that post-colonial critics were starting to mount against established ways of reading and evaluating literature, another challenge came from what were then the guerrilla camps of post-structuralism and deconstruction; a critique of this kind is provided in this Guide by an extract from Perry Meisel’s deconstructive reading of the novel as a textual process in which centres constantly shift and recede. But as far as Conrad was concerned, these new voices did not drown out the tones of more conventional scholarship and criticism; and chapter three of this Guide concludes with an extract from Ian Watt’s informed and suggestive analysis of impressionism and symbolism in Heart of Darkness.

In the new critical landscape of the 1980s, interpretations of Heart of Darkness seemed to take on fresh energy. Chapter four of this Guide discusses Benita Parry’s sustained critique of the novel as subverting but ultimately confirming imperialist ideology; Peter Brooks’s intriguing analysis of its narrative compulsions; Christopher L. Miller’s judicious exploration of its relation to Africanist discourse; and Nina Pelikan Straus’s forceful indictment of its sexism.

The final chapter looks at powerful readings of the 1990s that demonstrate the novel’s continued fertility: Gail Fincham’s analysis of the novel’s use of metonymy to portray a racist mentality; Edward W. Said’s deeply engaged reading of the novel as both complied with and critical of the discourses of imperialism and neo-imperialism; and Valentine Cunningham’s vividly detailed account of the relations between the textual activity of the novel and the material realities outside the text.

Heart of Darkness is a tale that takes the reader on a compelling, intriguing, rewarding and disorientating journey. This Guide offers a journey through the critical history of that tale that is itself intended to be compelling, intriguing and rewarding, but which also aims, as the good seaman Conrad might have wished, to provide some orientation, to offer compass and chart, to give bearings and reckonings, to enable us to make journeys and provisional mappings of our own. It does not have the imperialist ambition of trying to dominate and subdue the infinitely complex territory of Heart of Darkness; but it does seek to help its readers to know that territory better, in its detail, its uncanny likeness, and its difference.

Notes

1. Joseph Conrad, Notes on Life and Letters (London: Dent, 1921), p. 168.

2. Joseph Conrad, Tales of Hearsay and Last Essays (London: Dent, 1928; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1944), p. 110.

3. Conrad (1944), p. 113.

4. Karl, Frederick R. and Davies, Laurence, eds, The Collected Letters of Joseph Conrad: vol. 1: 1861-1897 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p.62.

5. Karl and Davies (1983), p. 61.

6. Conrad (1944), p. 113.

7. Karl and Davies (1983), p.61.

8. Karl, Frederick R. and Davies, Laurence, eds, The Collected Letters of Joseph Conrad: vol. 2: 1898-1902 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 139.

9. Karl and Davies (1986), pp. 139-40.

10. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 153.

11. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 157.

12. Karl and Davies (1986), pp. 157-58.

13. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 158.

14. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 175.

15. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 375.

16. Karl and Davies (1986), p. 407. This is a translation of a letter originally written in French, where the passage reads: ‘Histoire farouche d’un journaliste qui devient chef de station à l’intérieur et se fait adorer par une tribu de sauvages. Ainsi décrit le sujet a l’air rigolo, mais il ne l’est pas’ (Karl and Davies (1986), p.406).

17. Karl and Davies (1 986), p. 417.

Source: Joseph Conrad: “Heart of Darkness” (Icon Critical Guides) by Nicolas Tredell (1998)