by John L. Tancock

In the spring of 1904, Picasso returned to Paris from Barcelona, moving into the dilapidated building at 13, rue Ravignan that was to achieve universal fame as the Bateau Lavoir. Immersed in the nightlife of Montmartre, he turned to the theatres, circuses and cafes for subjects, creating the images of acrobats and performers which characterized his Rose Period.

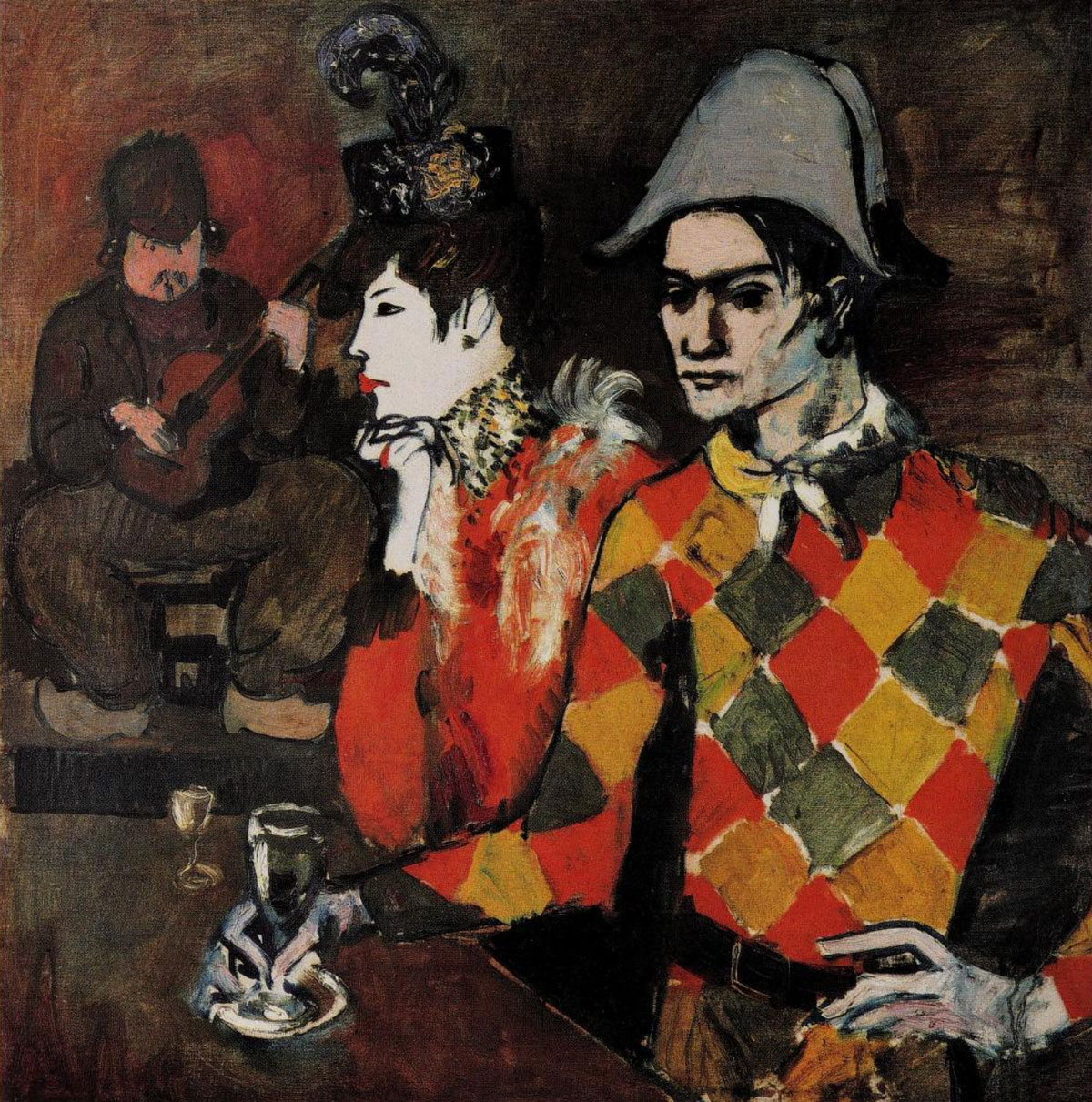

These themes had been of particular interest to French artists since the eighteenth century and perhaps even earlier. Callot, Gillot, Watteau and Gabriel de Saint-Aubin devoted many works to theatrical subjects, as did Daumier, Degas, Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec in the nineteenth century. Of more immediate significance to Picasso, perhaps, were two paintings by Paul Cézanne, Harlequin and Mardi Gras, in which the artist’s son Paul was portrayed wearing Harlequin costume. Picasso’s approach, however, differed fundamentally from that of any of his predecessors. It was not the spectacle itself that appealed to him, so much as the off-stage life, imagined and idealized to be sure, of the acrobats, harlequins and strolling players who lived among the booths of the fairs which lined the boulevards in winter. Picasso’s performers were generally seen either in the privacy of their own quarters or in desolate landscape settings. In Au Lapin Agile, however, he returned to the format of figures seated in a bar, used in two of his most striking images of 1901. Both Harlequin and Harlequin and his Companion focus on figures dressed in commedia dell’arte costumes, deep in thought and apparently unaware of anything around them.

The title Au Lapin Agile is derived from the name of a celebrated tavern, said to have started life as a shooting-box built by Henri IV. In 1903, it was purchased by Aristide Bruant, who leased it to Frédéric Gerard, known as Frédé. Under his lively guidance, and the name Lapin Agile, the café soon became the meeting place not only for writers associated with Montmartre but also for Picasso and Fernande Olivier, Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin, Modigliani, Cocteau, Max Jacob, Suzanne Valadon and her son Utrillo, who painted many views of it in the following years.

Here, the image of Frédé strumming his guitar in the background confirms the café as the setting, but the mood of the painting is far from festive. In fact, the obvious unhappiness of the principal figures evokes a tragedy that took place several years earlier. Picasso depicts himself as a brooding harlequin standing beside, yet totally alienated from, his female companion. This woman, the notorious Germaine Pichot, was one of three models Picasso and his young artist friends, Casagemas and Pallares, met soon after their arrival in Paris. Casagemas fell deeply in love with Germaine and his despair over the impossibility of their relationship led to his suicide in February 1901.

The death of his close friend had a profound influence on Picasso, and on his art. By late 1901, the bold confidence of works like Yo Picasso had given way to the isolation and melancholy of the works of the Blue Period. Both Casagemas and Germaine appeared in a number of paintings, with Germaine ultimately coming to represent the ‘fatal woman’ in Picasso’s imagination. However, it is in the painting’s image of himself that the depth of his sorrow is most clearly felt. As Theodore Reff has observed, ‘This typically modern sense of alienation is, of course, already found in Degas’ L’Absinthe and in the café and dance hall pictures of Toulouse-Lautrec (Miss May Belfort, 1895). Yet nowhere among the sordid or pathetic habitués of Lautrec’s world, and rarely even among the introspective acrobats and clowns of Picasso’s, is this suffering as intimately related to the artist himself, or as enigmatic as it is here. For its cause is apparently located not in the present but in an event that had occurred four years earlier and, above all, in his later brooding on the meaning of that event.’

Au Lapin Agile is a key work in deciphering Picasso’s state of mind as the Blue Period merged into the Rose Period. In giving the painting to Frédé, who hung it in his tavern (see photo below), Picasso chose not to conceal his anger, suppressed though it was. Alone among the paintings of the Rose Period, it is located in a definitely contemporary setting, quite unlike the idealized interiors of the later works. Picasso distances himself, however, from the world of Frédé and Germaine by depicting himself as Harlequin, an outsider defined by his timeless costume. In its subject Au Lapin Agile looks back to the past, but, in its ambiguity and juxtaposition of different levels of reality, suggested principally by costume, it looks forward to the much more jarring stylistic dissimilarities of a work painted only two years later, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

SOURCE: Sally Prideaux, Sotheby’s art at auction 1989-90