Italians, even some of Guido Morselli’s closest friends, discovered only very recently that a formidably original novelist was lost when Morselli took his own life in 1973, at the age of sixty. Up till then not one of his novels had been accepted for publication — seven are now available in Italy — and all had been turned down by numerous publishers. How could such a major talent go unrecognised? The ‘Morselli affair’ compelled the literary establishment to ask itself some awkward questions. The easiest explanation for the rejection is that his work is unlike anything else in post-war Italian fiction.

But the rejection was to some extent mutual. ‘They say that in solitude lies the only true happiness,’ he wrote at thirty-five in Realismo e fantasia (Realism and Fantasy, 1947), an ambitious volume of philosophical dialogues, the second of the only two books he saw through the press, ‘but in fact it is not so, indeed it is often no happiness at all. For some people solitude is a duty.’ The little house he built for himself in a solitary mountain valley between Como and Lake Maggiore was the outward sign of this compulsion. With it went a deep love of the countryside, and a growing revulsion against modern life and its worst excesses, which in his last book he named Brutality, Pollution, Money-fever, and the wholesale Uglification of the world.

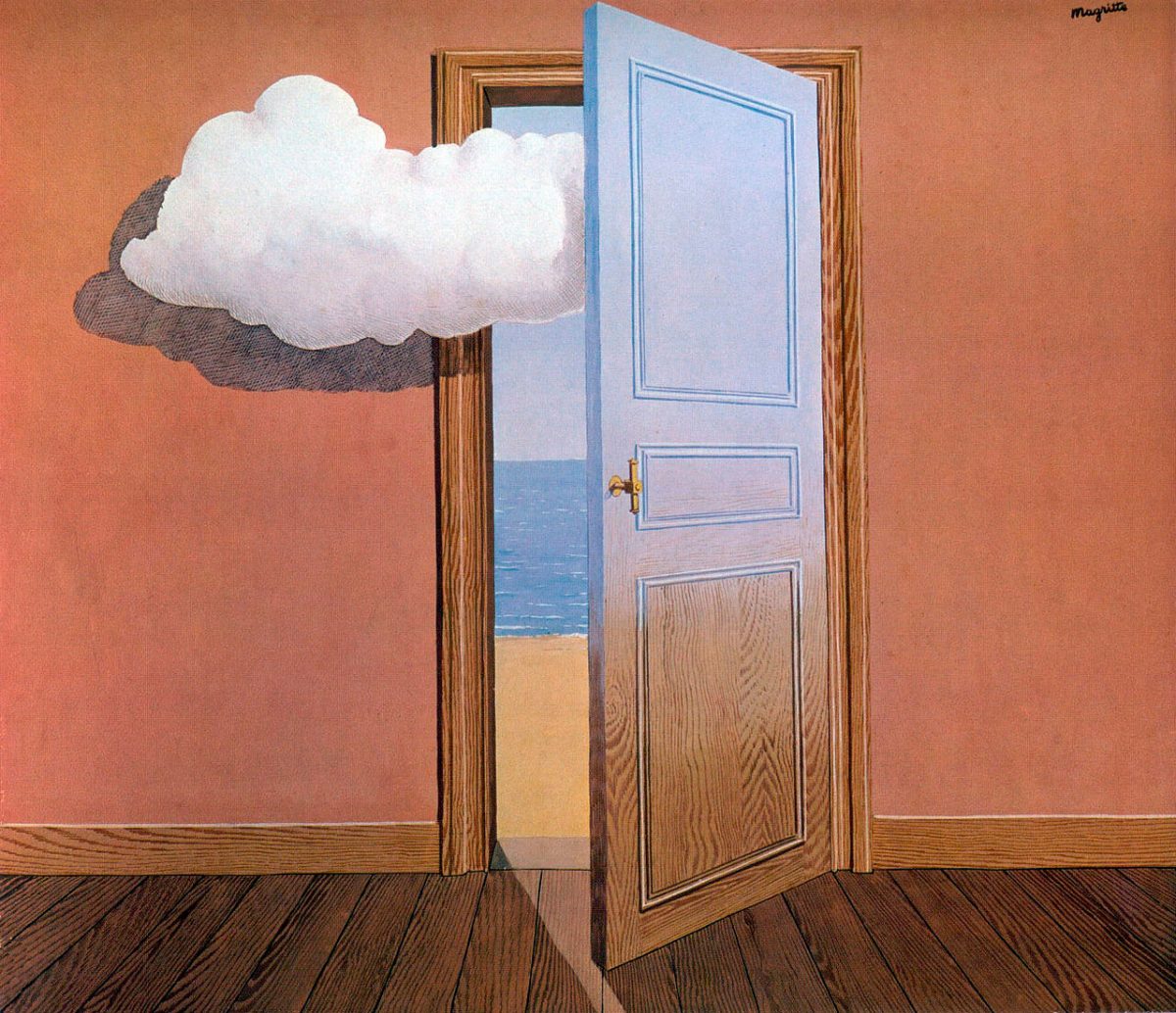

‘Sometimes we would spend hours on end going over many things from the past,’ a woman who was close to him recalls, ‘old songs, old fashions, old trams, old trains (about which he knew everything), old streets, old houses that are gone. And yet he used to say he could happily have spent three months all alone on the moon.’ In his bitter, self-confessional last novel, Dissipatio H. G. (The Dissolution of the Human Race), he insists it would not be right to call him a misanthrope, a hater of mankind; more accurate would be ‘phobanthrope’, one who lives in fear of the human race. An old game with him, he goes on, was to imagine the world as his alone, exclusively ‘with me and for me’, miraculously emptied of any other human presence. The poetic justice or divine punishment which he imagines for himself in that defiant, tragic book is a terrifying paradox: after deciding to drown himself in a mysterious subterranean Lake of Solitude because the presence of humanity has become too oppressive to live with, his body refuses at the crucial moment to execute the order and he returns to the world to discover that his day-dream has become an irreversible reality: the entire human race has ‘passed away’. One of the revelations which he receives is that it is not the end of the world. ‘What were they, what did they do?’ the rest of nature asks after ‘the great simplification’. ‘They were neither necessary nor useful.’ Maybe Morselli would have denied the infantile element in that deadly serious day-dream (he scorned Freud and childhood has no role in his fiction) but it shows what contradictory instincts within himself he had to fight against to achieve the adult courage, the fearless intelligence of his best work.

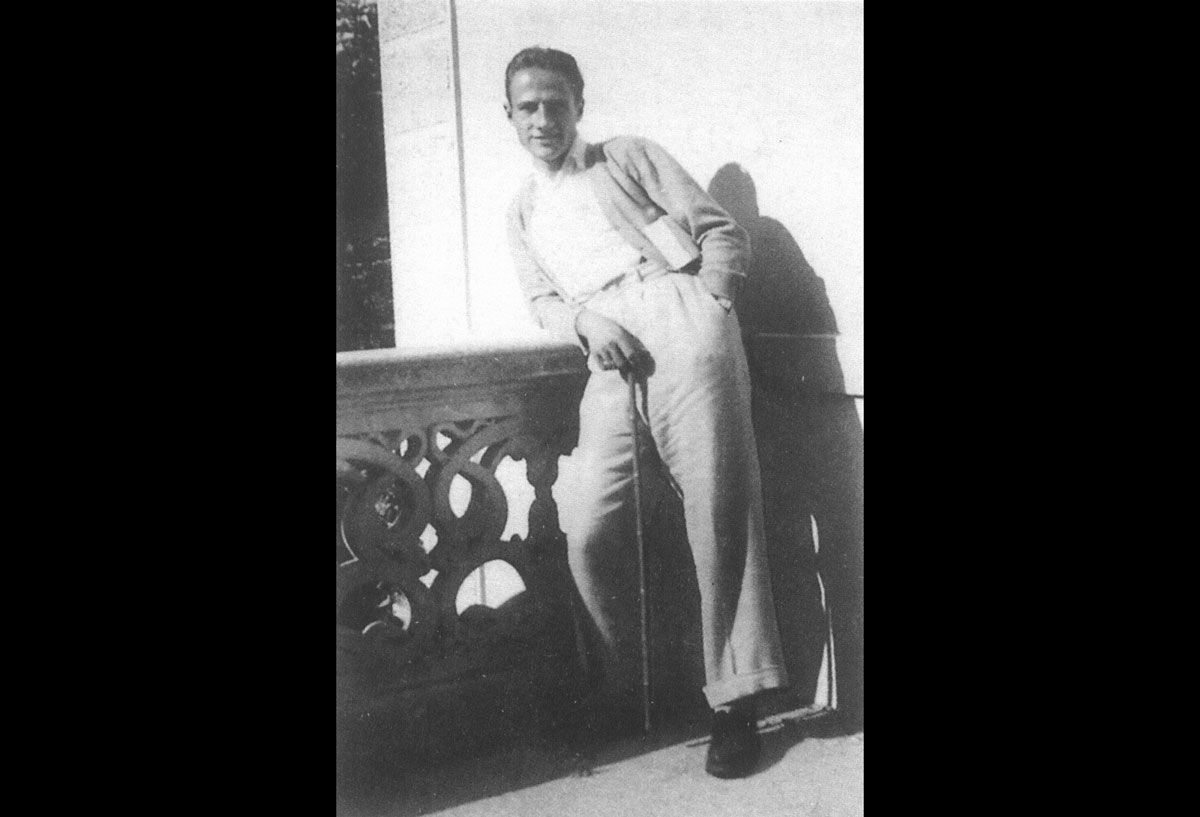

‘Too many women, too much solitude, too many eccentricities,’ is the way a Catholic critic rather censoriously summed up Morselli’s life in an article that otherwise generously argued (against other theologians) that the writer’s suicide was not incompatible with the religious spirit his work often reveals. He was born in 1912, the second of four children, and grew up in Milan, where his father was president of Italy’s largest pharmaceutical company. His mother died when he was twelve. He missed her bitterly, but he also came to develop a profound admiration for his father, a strong-willed, hardworking man, and in the years after his father’s death Morselli said he dreamt of him almost every night. Despite his cult of aloneness, Morselli’s fiction is peopled with clear, positive-thinking men who stand out from their fellows for their unselfish honesty and realism.

It was largely to please his father that he read law at Milan University, but then, instead of settling down to a career, he travelled widely, including quite a long residence in England. Before being called up in 1940 on Italy’s intervention in the war he had already tried his hand at some short stories and newspaper articles on current affairs, military history and railways. Until the last ten years of his life he continued to contribute occasional pieces to the cultural press on a wide variety of subjects, in particular history, philosophy, religion and literature. He was exceptionally fluent and well-read in the major European languages; in fact his non-conformism and an aversion to all rhetoric and excessive emotion gave him a spontaneously pan-European cast of thought, an anti-nationalism which in his fiction finds a geographical centre in the cultural diversity of old Austria, or in a lifelong love-hate relationship with polyglot, solid, neutral Switzerland.

Something of a manic depressive, his name for the human quality he most valued was serenity, ‘the faculty of seeing the world as it really is’. In his philosophical writings it figures as a constructive balance between the polar opposites of ‘fantasy’ (subjectivity, introversion, idealism) and ‘realism’ (objectivity, participation, materialism). In his first published work, a lucid monograph on Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu, which he found time to write while he was a subaltern in Mussolini’s army, he defined the consummate artist as ‘a sensitive man with an exceptional fascination for ideas’ and characteristically emphasised the outward-looking facets of Proust’s intelligence: ‘curiosity, clarity, versatility’.

Morselli experienced the carnage of war (‘the most catastrophic and futile in history’) in Southern Italy during the Italian debacle of July—September 1943. When his unit was disbanded he remained marooned in Calabria for nearly three years, homesick and penniless, unable to get word to his family or to the woman he loved. In this intensely lonely period he began the extensive working journal which he kept for the rest of his life, drafted a first novel and the long philosophical dialogues, and at least at one point contemplated suicide. After the liberation of the north his father offered him a position in business, but Guido refused. ‘The true artist,’ he had already written in his Proust, ‘impervious to taunts or cajolements shuts himself up in his ivory tower, since only in isolation can he be of value to his fellow man, labouring to offer him the incomparable gift of his work.’

That was the unashamedly romantic side of the man, and although he came to learn to treat it with irony and not a little suspicion he never abandoned the principle in either his thinking or his practice. For the rest of his life he lived (modestly) off the family fortune and his work was his writing. The experience of war and his long exile in Calabria left him with an extreme sensitivity to noise and a hatred of any form of travel, especially tourism. For twenty years he lived in his secluded valley beside a mountain called the Field of Flowers, surrounded by woods and wild animals, with distant views of Monte Rosa and the glaciers of the Bernese Oberland. Three months before he shot himself he had fled his home, following a desperate battle to block a planners’ decision to construct a highway and maddened by the din of motor-cross enthusiasts who had popularised the valley.

After his early attempts at novel-writing in the 1940s, and a long interim of further journalism, plays, a film-script, two volumes of intense religious speculation and even a rigorous attempt to exorcise his demon in a ‘Short Treatise on Suicide’, he made a determined return to fiction in 1961. In Un dramma borghese (A Bourgeois Drama), a work of desolate realism, which seems to have been written in a fit of misogyny, the ‘drama’ is an eighteen-year-old daughter’s passion for her widowed father. Rigidly schematic, it is a study of two unstable people tragically unmatched in intelligence (his) and emotion (hers). It is also a conscious challenge to prevailing orthodoxies of cultural politics in Italy, confronting its Oedipal theme with nothing but contempt for Freudian notions of the unconscious and presenting a resolutely uncommitted ‘conservative’ hero. In fact the real topic is Morselli’s intriguingly ambiguous portrait of himself in the shape of an egocentric middle-aged neurotic fearfully defending his precariously constructed peace of mind from ‘invasion’ by others. Morselli admired altruism but he seems to have found it so rare that it never failed to astonish him. Shocking to the reader is not the father’s sexual response to his daughter, but his incapacity to show a glimmer of affection for another human being in desperate need. Suicide, treated ironically, is a theme that runs through the book from beginning to end.

The title of his next novel, Il comunista (The Communist), does not indicate a political conversion, although one of Morselli’s many serious intellectual interests was socialist thought and he was proud of his own ‘evolutionary’ version for which he coined the name ‘socialidarity’. After having explored the negative side of his own ego so exhaustively he now suddenly reveals his astonishing versatility (‘If they’d only publish me,’ he used to say, ‘I could treat a different subject every day.’), in particular a rare intuitive ability to evoke social or historical contexts remote from his own direct experience, and in a language which seems to speak faithfully for them. His working- class protagonist, an ex-railwayman and communist activist, is the first of his positive heroes, men whose talent lies in their creative approach to real life, a capacity to ‘leave a mark on things and people’. Il comunista is also the tragic story of a man of sincere faith whose heresy is to assert, to the consternation of his party’s official ‘theologians’, that no future society will ever eliminate the evil of work, understood as a biological fatality rather than an economic law, ‘a state of continual tension’. In the mid-fifties Morselli had written a courageous volume of religious philosophy, Fede e critica (Faith and Criticism), largely concerned with the problem of evil, seen not as the devil’s work but God’s, and in its specific form of human pain and unhappiness, sickness and toil, conflict and war. Job is his hero, honoured for refusing to accept the orthodoxy that his intolerable misfortunes and sufferings could be his own fault or sin.

Veiled by many levels of grotesque irony, the same theme, ‘the insoluble problem’, also lies at the heart of Roma senza papa (Rome without the Pope), the most successful of his novels in Italy. Once again Morselli astonishes by the complete change of style and mood. Set in the year 1997 but written during the pontificate of Paul VI, the first globe-trotting pope, it is a wickedly inventive satire which makes a meal of the contradictions inherent in attempts to liberalise Roman Catholicism. Drugs are prescribed for instant mysticism, celibacy is eccentric, confessionals are computerised, euthanasia is okay and the GID (God Is Dead) movement is doing well among the seminarists. But Rome’s greatest tourist asset, the Pope, has deserted the noisy circus of the eternal holiday city. His country retreat is not the luxury of Castelgandolfo but a little cluster of whitewashed buildings with green shutters in the middle of a field. When John XXIV, an Irishman and a keen tennis player whose life’s work has been to demonstrate that everything has already been said, finally condescends to hold an audience, he laconically informs everyone that ‘God is not a priest.’

Contro-passato prossimo (Past Conditional), completed in 1970, is Morselli’s most ingenious work and his most optimistic, as though the failure of his hope in God had suddenly given him new faith in man. How it was never accepted for publication is beyond understanding, for it is an extraordinary feat of imagination and intelligence. With the materials of reality he conducts a cool experiment to challenge conventional notions of the historical process and demonstrate that nothing need necessarily happen as it does. Taking the whole context of European history as found in 1916 he proceeds vividly to chronicle a no less incredible sequel than the ‘real’ events: through just as plausible a combination of unfathomable accident and human design, a united Europe eventually emerges after victory goes to the Central Powers in time to prevent America’s intervention in European affairs. Morselli’s ‘counter-history’ celebrates the (impossible?) triumph of tolerance and reason over chauvinism and fanaticism and in great part it is achieved by the co-operative work of a small number of independent-thinking politicians and individuals, ‘men of imagination and decision’.

The unnamed hero of Divertimento 1889 is hardly notable for his imagination or decision. This man with one of the most ‘loathsome and alienating’ of jobs and a deep longing to escape from it, is united Italy’s second monarch, King Umberto I, a rather less absolutist and certainly more conventional figure than his father, the national legend, Vittorio Emmanuele II. Like the old King he had little time for parliament and politicians, much more for military matters and mistresses: the Duchess Litta was already his official lover before his marriage to his beautiful cousin, Margherita, and remained so, not without rivals, until the end. Morselli’s account of Umberto’s character — the brisk military turn of mind and phrase, his philistinism, the moments of uncertainty and the lack of self-assurance, the streak of fatalism — all correspond to the historical record. In an obituary notice Reuter’s man in Rome praised the ‘simplicity of his habits’ and ‘the unostentatious way in which he performed his duties’. But for his own good reasons Morselli underplays the extent of the King’s actual power, for in foreign and colonial policy and at certain moments of political and social tension Umberto I carried quite a lot of weight. Morselli, incidentally, knew the complications of keeping two or more women going at once. And one sees how a King who complains he has mountains of paperwork and no one who listens to him might earn the wry commiseration of a prolific unpublished novelist.

1889 did not bring too many unexpected headaches for His Royal Highness. The government under the volatile Sicilian, Francesco Crispi (fiercely anti-French champion of the ‘Triple Alliance’ between Germany, Austria and Italy), and his coolheaded Treasury Minister, the Piedmontese Giovanni Giolitti, had major bank scandals and a severe financial crisis to contend with. But in nineteenth-century Italy the monarchy was not too popular an institution in many quarters. The Papacy could not forgive the House of Savoy for seizing Rome, while Radicals, Socialists, and of course Republicans, were all nominally pledged to remove the King, and anarchist groups did not intend to work through parliament to do so. In fact, like Morselli himself (who was morbidly attached to the company of his pistol, his ‘blackeyed girl’), King Umberto was marked to die by the bullet. After two earlier assassination attempts (one in the first year of his reign) he was shot through the heart by an anarchist assailant in Monza on 29 July 1900. The King’s open carriage had just set out to return to the Palace after he had distributed prizes at the local Gymnastic Society. His assassin, a silk-worker, had vowed to execute him for what was not the first but probably the worst blunder of his career: the notorious telegram which he sent to General Bava Beccaris awarding him the Cross of Savoy and congratulating him on the service he had rendered ‘to our institutions and to civilisation’ by putting down unrest on the streets of Milan leaving 81 dead and 502 wounded.

Morselli wrote Divertimento 1889 immediately after his hard labour on Contro-passato prossimo, and in keeping with the King’s holiday mood and enviable disinclination to plumb the depths of his own soul this light-hearted ‘entertainment’ reads like a joyous vacation from its author’s tragic themes and personal obsessions. They are all there beneath the good-natured, surface.

—Hugh Shankland, 1986

From the introduction to Guido Morselli, Divertimento 1889, E.P. Dutton, New York, 1986