by Charles Fantazzi

It is disturbing to read this book with the knowledge that the author took his own life a few months after its completion in 1973. Since his tragic passing, five of his novels, unjustly rejected by the big-name publishers of Italy, have now been issued posthumously by Adelphi and have earned much critical attention. The protagonist of this prophetic last work is the sole survivor of the human race (H.G. of the title, which is taken from a Latin translation of the neo-Platonic philosopher Iamblichus, stands for humani generis) who ironically has returned to the world after attempting an elaborate mode of suicide in a subterranean lake inside a mountain. In a brief instant at two o’clock in the morning of 2 June all of humanity has been volatilized, “dissipated” into nothing, leaving behind merely the outline of their human forms, like some kind of larval shell or the last traces of a Pompeian corpse left in the volcanic ash. Rushing off to a girlfriend’s apartment, the lone survivor discovers his loved one’s shape still discernible beneath the bed-sheets, and the imprint of her head still fresh on the pillow.

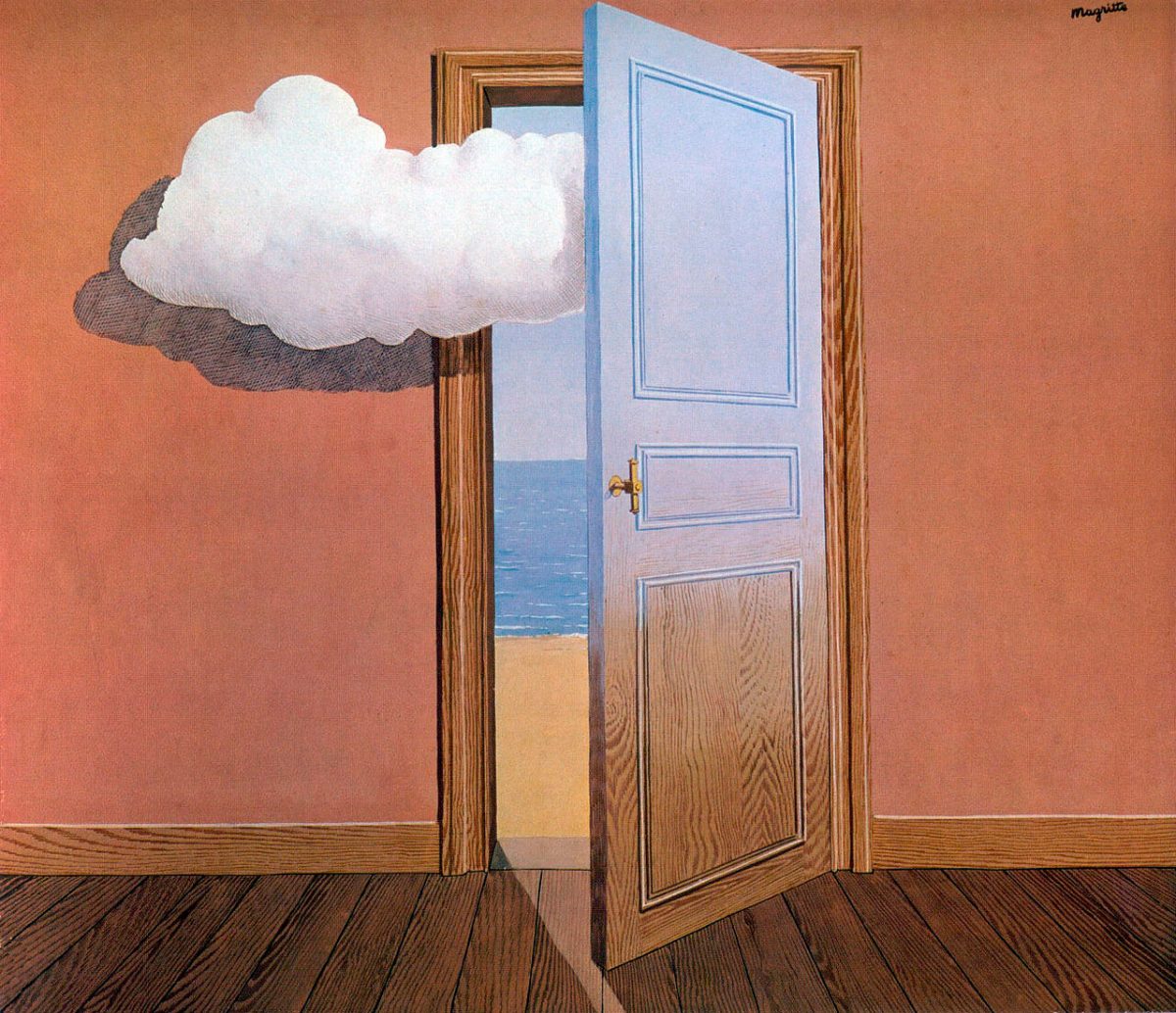

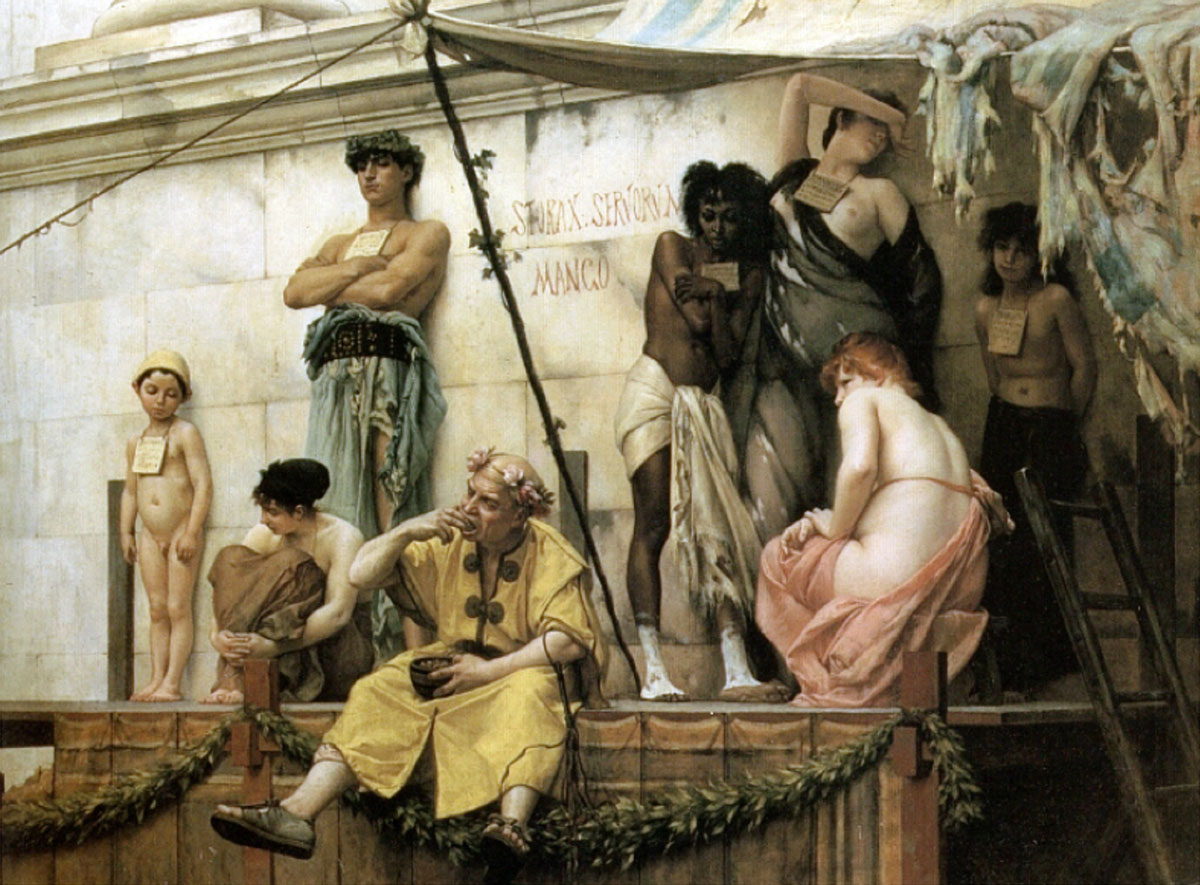

Other forms of animal and plant life continue to exist, however, and all of man’s material accomplishments remain intact (shades of the “clean” neutron bomb before its advent!), functioning as usual; automated announcements of flights at the airport and recorded responses over the telephone keep droning out their empty and irrelevant messages. In an attempt to discover some explanation for this sudden destruction of the human race, the last “ex-man” reasons to himself that perhaps extreme materialism has produced immateriality in the manner of a Dantesque contrappasso. A world that was all body has become disembodied, and the great Enemy of the world, man, has been eliminated. It has been a typical arrogant assumption on the part of this destructive inhabitant of die planet to think that his own end would inevitably involve a universal cataclysm. The unbiased truth is that as things began without man, so they will finish tranquilly without him.

Wandering through this disinhabited world, the protagonist tries to communicate with the dead, piecing together fragments of memories and searching after some other survivor, in particular, a psychiatrist friend, Dr. Karpinsky. At times he wonders if he himself is dead, or if perhaps as sole survivor he is really a condemned man rather than a privileged member of the species. On the other hand, the natural world gains new confidence, creatures of the night sing more freely, and at the end in the streets of Chrysopolis (clearly Zurich, the financial capital of Europe) a thin cover of earth reemerges and wild plants begin to grow again. Chicory and crowfoot sprout in the marketplace of marketplaces, while the last man sits and waits for Karpinsky with a pack of Gauloises in his pocket.

—Charles Fantazzi

University of Windsor

Source: World Literature Today, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Spring, 1978), p. 270 Published by: Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma