Alan Watts draws a more accurate description of nature—not as something separate from man, but in its original sense, as the virtues or characteristics of nature, including the seemingly senseless expressions of mankind run amuck with aimless technology and its resulting inevitable alienation.

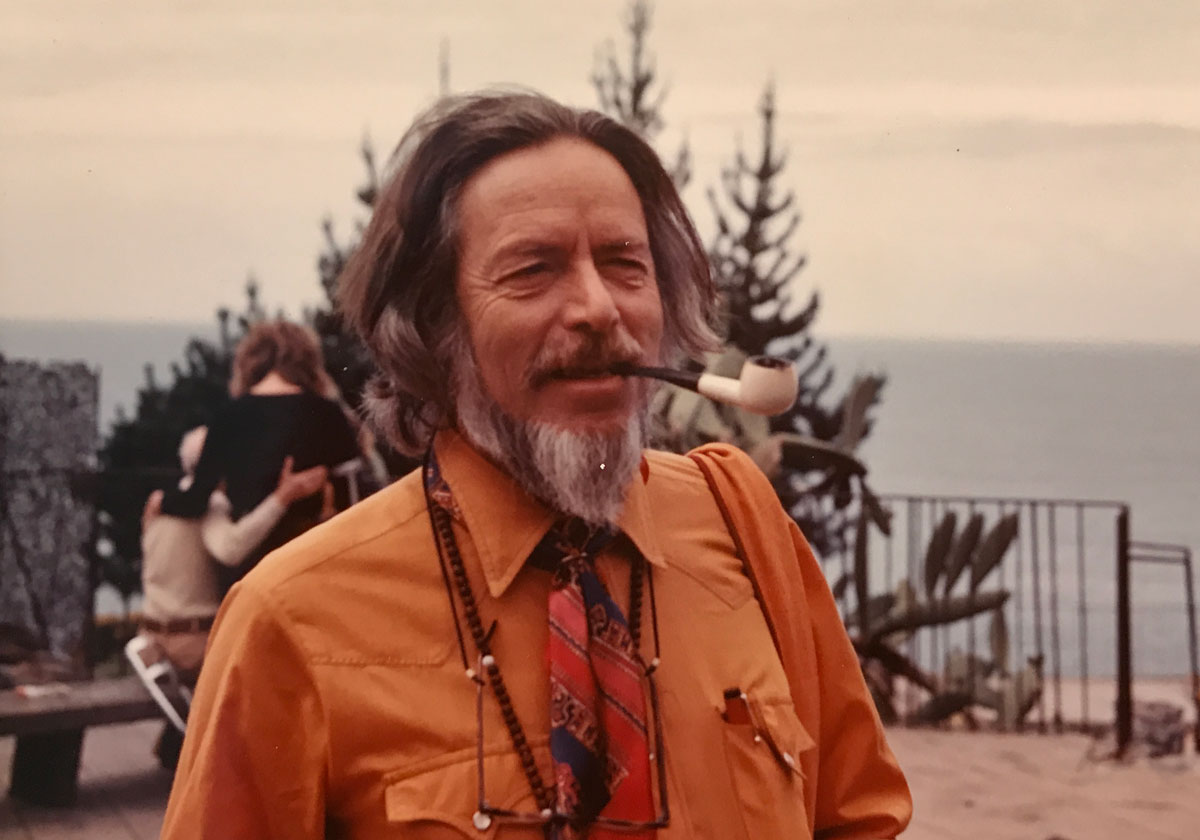

by Alan Watts

I was talking to you this morning about the basic philosophy of nature that underlies Far Eastern culture, and explaining why it’s so important for us in the West to understand this, so that we can encourage the Japanese people to re-understand it—because they are in danger of following some of our wildest excesses, and doing things that will destroy our environment. You see, a great deal of what we have done by way of technological development is based on the idea that man is at war with nature, and that in turn is based on the idea, which is a really a 19th century myth, that intelligence, values, love, humane feelings, etc. exist only within the borders of the human skin. And that outside those borders the world is nothing but a howling waste of blind energy, rampant libido, and total stupidity.

This you see, is the extreme accentuation of the platonic Christian feeling as man as not belonging in this world, of being a spirit imprisoned in matter. And it’s reflected in our popular phraseology. “I came into this world.” “I face facts.” “I encounter reality.” It’s something that goes “boom” right against you like that!

But all this is contrary to the facts. We didn’t come into this world—we grew out of it, in the same way that apples grow out of an apple tree. And if apples are symptomatic of an apple tree, I’m sure that after all, this tree apples—when you find a world upon which human beings are growing, then this world is humane, because it humans.

Only we seek to deny our Mother, and to renounce our origins, as if somehow we were lonely specimens in this world, who don’t really belong here, and who are aliens in an environment of consisting mostly of rock and fire, and mechanical electronic phenomena, which has no interest in us whatsoever, except maybe a little bit in us as a whole, as a species. You’ve heard all these phrases, “Nature cares nothing for the individual, but only for the species.” “Nature as in tooth and claw.” “Nature is dogear-dog,” or as the Hindus call it Matsyanaya the Law of the Sharks. And so, also a very popular idea of the 19th century running over into the common sense of the 20th, is that we belong as human beings on some very small, unimportant spec of dust, on the outer fringes of a very small galaxy, in the middle of millions and millions of much more important galaxies. And all this thinking is pure mythology.

Let me go in a little bit to the history of it, because it’s important for us as Westerners to know something about the history of the evolution of our own ideas that brought this state of mind about. We grew up as a culture in a very different idea, where the universe was seen as something in which the earth was at the center, and everything was arranged around us, in a way that we of course as living organisms naturally see the world. We see it from the center, and everything surrounds us. And so, this geocentric picture of the world was however, one in which every human being was fantastically important, because you were a child of God, and you were watched day in, day out, by your loving and judging father in Heaven. And you, because you have an eternal life, are infinitely important in the eyes of this God.

I have a friend who’s a convert to Roman Catholicism, and is a very sophisticated and witty woman. And in her bathroom she had one of those old-fashioned toilets with a pull-tank on the top, and a pipe down to the toilet seat. And fastened on this pipe there was a little plaque which had on it nothing but an eye. And underneath was written in Old English Gothic style letters: “Thou God sees me.” So everywhere is that watching eye, that examines you, and at the same time as it knows you, it causes your existence. By knowing you, God creates you, because you are an act of His creative imagination. And so you are desperately important.

But Western people got this feeling that this became too embarrassing. You know how it was as a child, when you were working in school, and the teacher walked around behind your back, and looked over while you were working, and you always felt put off. While the teacher is watching you, you are non-plussed. You want to finish the work and then show it to the teacher. There is a problem. Never show anything unfinished to children or to fools. And children feel this very strongly about their teachers. They want to finish it before it’s looked at.

So in exactly the same way, it’s embarrassing to feel that your inmost thoughts and your every decision is constantly being watched by a critic, however beneficent and however loving that critic may be, that you are always under judgement. To put this to a person is to bug him totally. Indeed, it’s one of the techniques used in Zen for putting people into a very strange state of mind. You are always under watch.

It was a great relief for the Western world when we could decide that there was no-one watching us. Better a universe that is completely stupid than one that is too intelligent. And so, it was necessary for our peace of mind, and for our relief that during the 19th century particularly, we got rid of God, and found then that the universe surrounding us was supremely unintelligent, and was indeed a universe in which we, as intelligent beings, were nothing more than an accident. But then, having discovered this to be so, we had to take every conceivable step, and muster all possible energy to make this accident continue, and to make it dominate the show. The price that we paid for getting rid of God was rather terrible. It was the price of feeling ourselves to be natural flukes, in the middle of cosmos quite other than ourselves—cold, alien, and utterly stupid, going along rather mechanically, on rather rigid laws, but heartless.

This attitude provoked in Western man a fury to beat nature into submission. And so, we talk about war against nature. When we climb a mountain like Everest, we have conquered Everest. When we get out enormous phallic rockets and boom them out into space, we’re conquering space. And all the symbols we use for our conquest of nature are hostile: rockets, bulldozers… this whole attitude of dominating it, and mastering it.

Whereas a Chinese person might say, when you climb a high mountain, “You conquer it? Why this unfriendly feeling? Aren’t you glad the mountain could lift you up so high in the air, so as to enjoy the view?” So this technology that we have developed, in the hands of people who feel hostile to nature is very dangerous. But the same technology in the hands of people who felt that they belong in this universe could be enormously creative. I’m not talking some kind of primitivism, as if we should really get rid of all technology, and go back to being a kind of primitive people, but rather that, in the hands of people who really know that they belong in this world, and are not strangers in it, technology could be a wonderful thing. For one sees, in the art forms that have been developed through this philosophy, that we have a combination. My friend Sabro Hasegawa, a great Japanese artist of modern times, used to call it the “controlled accident.” That there is on one hand, the unexpected thing that happens of itself that nobody could predict—that’s the accident. And there is, on the other hand, prediction, control, the possibility of directing something along certain lines, just as when the sailor moves against the wind, with the power of the wind, he is using skill to control the wind. So, in the same way our controlling things has a place, but it is with the accidental world of nature, rather than against it.

So then, this is why the philosophy of nature, and the civilization of the Far East is immensely important to us to understand, with our vast technical powers. And again in turn we, understanding that point of view, are immensely important to the people of the Far East, so as to help them not to be too intoxicated by our way of doing things. There’s a long, long story about why technology developed in the West first, rather than in the Far East, and I’m not going to go into that for the moment. But the important thing about this whole philosophy of nature, and of man’s place in nature is that this Taoist, and later Zen Buddhist, and Shinto feeling about man’s place in the world is today corroborated by the most advanced thinking in the biological and physical sciences. Now, I can’t stress that too much.

Science is primarily description, accurate description of what’s happening, with the idea that if you describe what is happening accurately, you’re way of describing things will become a way of measuring things. And that this in turn will enable you to predict what is going to happen. And this will build you some measure of control over the world. The people who are most expert in describing, and who are most expert in predicting are the first people to recognize the limitations of what they’re doing.

First of all, consider what one has to do in science, in a very simple experiment, in which you want to study a fluid in a test tube, and describe what is in that fluid so accurately, that you must isolate that fluid from what are called “unmeasurable variables”. I have a fluid in a test tube, and I want to describe it accurately, but every time the temperature changes, my fluid changes, so I want to keep it free from changes of temperature. This already implies an air conditioning system. Also, I don’t want my fluid to be jiggled, because that may alter it. So I’ve got to protect it from trucks that go by the lab. And so I have to build a special bump-proof room, where trucks won’t jiggle it. Also, I have to be very careful that when I look at this fluid I won’t breathe on it, and affect it in that way. And that the temperature of my body, as I approach it won’t alter it. And I suddenly discover that this fluid in a test tube is the most difficult thing to isolate in all the world. Because everything I do about it affects it. I cannot take that fluid in a test tube and take it out of the rest of the universe, and make it separate and all by itself.

A scientist is the first to notice this. Furthermore, he knows not only that it’s his bodily approach that alters things, he finally discovers, in studying quantum theory, that looking at things changes them. So when we study the behavior of electrons, and all those sub-atomic particles, we find out that the means we use to observe them changes them. What we really want to know is, what are they doing when we’re not looking at them? Does the light in the refrigerator really go out when you close the door? So what will it do when it’s not being watched? Because we found out that watching them affects them. Why, because of course, in order to observe the behavior of sub-nuclear particles, we have to shine lights on them, as it were. We have to bombard them with other nuclear particles, and this changes them. And so we get to the point where we can know the velocity of the particle, without knowing its position, or know its position without knowing its velocity. You can’t know both at the same time. What all that is telling us is—we cannot stand aside as an independent observer of this world, because you the observer are what you’re observing. You’re inseparable from it.

Let me put it in another way. Science, I said, was accurate description. We want to describe the behavior of any given organism, whether it’s human, or whether it’s an ant, or whatever it is. Now how will you tell, how will you say what an ant is doing without describing at the same time, the field or the environment in which the ant is doing it. You can’t say that an ant is walking, if all you can describe is that this ant is just wiggling its legs. You have to describe the ground over which the ant is walking, to describe walking. You have to set up directions, points of the compass, etc. And so, soon you have to describe all the ant’s friends and relations. You have to describe its food sources. And so you soon discover that although you thought you were talking about an ant, what you are actually talking about is an ant environment… a total situation from which the ant is inseparable. You’re describing the behavior of the environment in which ants are found, and that includes the behavior of ants.

So too, human behavior involves first of all, the description of the social context in which human beings do things. You can’t describe the behavior of an individual, except in the context of a society. You’ll have to describe his language. Indeed, in making a description I have to use language which I didn’t invent. But language is a social product. Then beyond human society there is the whole environment of the birds, the bees and the flowers, the oceans, the air and the stars. And our behavior is always in relationship to that enormous environment—just like our walking is in relation to the ground, and in relation to the form of space, object outlines and the shape of a room.

So then, the result that comes out of it, is that the more and more the scientist looks at an organism, he knows that he is not looking at an organism in an environment, he’s looking at a total process, which is called “organism” out of its environment. But he suddenly wakes up and sees that he has a new empathy with that which he is studying. He started out to say what the organism is doing. He found that he had to paste up a few steps, and to realize that his description of the behavior of the organism involved, at the same time, a description of the behavior of the environment. So that although, unlike trees and plants, we are not rooted to the ground, but walk about fairly freely inside our bags of skins, we are nonetheless as much rooted in the natural environment as any flower or tree.

This gives us at first, as Westerners, a sense of frustration, because we say, “It sounds fatalistic.” It sounds as if we were saying, “You thought you were an independent organism—you’re nothing of the kind. Your environment pushes you around. But that idea simply, if we would express that idea as a result of hearing what I’ve just said, it would mean that we didn’t understand it. You see, what was high knowledge a hundred years ago, is today common sense. And most people’s common sense today is based on Newtonian mechanics. The universe is a system billiard ball of atomic events, and everybody regards his ego as an atomic event—a fundamental part, component of the universe. All right? So all these billiard balls start going clackety-clackety-clack, and knocking each other about. And so, you feel yourself to be, perhaps, one billiard ball pushed around by the world, or sometimes if you can get enough up inside that billiard ball, you can do some pushing of the world around. But mostly it pushes you.

You read B.F. Skinner, the supreme behaviorist psychologist, and he describes all phenomena of nature in terms of man being pushed around. But let’s suppose that we live in a world where things don’t get pushed around, and can’t be pushed around. Supposing there’s no puppet. Supposing there is no cause and no effect. That instead of things being pushed around, they are just happening, the way they do happen. Then you get an utterly different view, and this is the view with which we are dealing, lying behind this culture.

As I said this morning, there is no boss. You as a human being are not going to push this world around, but equally, you are not going to be pushed around by it. It goes with you. The external world goes with you, in just the same way as a back goes with a front. How would you know what you meant by “yourself,” unless you knew what you meant by other. How would the sun be light, if you didn’t have eyes. How would vibrations in the air be noisy, if you didn’t have ears? How would rocks be hard, if you didn’t have soft skin? How would they be heavy, if you didn’t have muscles? It’s only in relation to eyes that the sun is light. It’s only in relation to a certain kind of nervous system that fire is hot. And it’s only in relation to a certain musculature that rocks are heavy. So that the way you are constituted, the way your organism is formed calls into being the phenomenon of light, and sound, and weight, and color, and smell.

There is a koan in Zen Buddhism, “What is the sound of one hand?” There is a Chinese proverb that says, “One hand does not make a clap. So if two hands clap, make the clap. What is the sound of one hand?” You see, what a silly question. And yet everybody is trying to play a game in which one side will win, and there can be one hand clapping—to get rid of the opposite. Light get rid of darkness. I conquer the universe. In other words, I play the game that I am going to get one up on them, and hold my position. I am going to dominate the other. And as soon as we get into that particular kind of contest we become insane. Because what we’re doing is pretending that there can be an in-group without an outgroup.

Let me just give a few illustrations of this from contemporary social situations. You, or most of you here, on the whole identify yourself with the nice people. In other words, you live fairly respectable lives, and you look down upon various other people who are not nice. And there are various kinds of not-nice people.

In Sausalito, where I live, they’re called “Beatniks”. They are people who wear beards, and who live along the waterfront, and who don’t follow the ordinary marriage customs, and who probably smoke marijuana instead of drinking alcohol, because alcohol is the drug for nice people.

What the nice people don’t realize is, they need the nasty people. Think of all the conversation at dinner tables that you would miss, if you didn’t have the nasty people to talk about. How would you know who you were, unless you could compare yourselves with those who are on the out? How do those in the church, who are saved, know who they are unless they have the damned. Why St. Thomas Aquinas let it out of the bag and said that in Heaven, the saints would look over the battlements of Heaven, and enjoy the just sufferings of the souls in Hell. Jolly won’t it be, to watch your sister squirming down there, while you’re in bliss. But, that was letting the cat out of the bag, because the in-group can’t exist without the out-group.

Now in my community in Sausalito, where the outgroup is sort of Beatniks, they in their turn know that they are the real in-group, and that up on the hill, those squares who are so dumb that they waste all their days earning money by dull work to buy pseudo-riches, such as Cadillacs and houses with mowed lawns, and wall-to-wall carpeting, which they despise, they feel very, very much collective ego strength by being able to talk against the squares. Because the out-group makes itself the ingroup by putting the in-group in the position of an outgroup. But both need the other one. This is the meaning of saying, “Love your enemies,” and pray for them that despitefully use you, because you need them. You don’t know who you are without the contrast. So, love your competitors, and pray for them that undercut your prices. You go together, you have a symbiotic relationship, even though it be formally described as a conflict of interest.

Now to see that kind of thing is the essence of this philosophy of nature. It goes together with the idea of the Yang and the Yin, that we don’t know what the Yang is, the positive, the bright side, unless we at the same time, know what the Yin is, which is the dark side. These things define each other mutually. And to see that, you might think at first, was to settle for a view of the world that was completely static. Because after all, if white and black, good and evil, are equally pitted against one another, then so what? It all boils down to nothing.

But the universe is not arranged that way, because it has in it the principle of relativity. Now you would think, in a Newtonian and respectable Platonic universe the earth would revolve around the sun in terms of the perfect circle, but it doesn’t, it’s an ellipse. And if it were a perfect circle, the earth wouldn’t revolve, because there would be no go to it. See, when you take a string with a ball on the end, and you swing it ’round your head, you don’t describe a perfect circle. You know what happens? There’s one moment in that swing when you have to give the thing a little charge of strength, you go whoop, whoop, whoomm, whoomm, whoomm, brrumm, brrumm,—and that little pulse sets the thing going. Listen to your heart. How does it go? It doesn’t go “pum, pum, pum, pum, pum, pum, pum,” but “pum-pum, pum-pum, pum-pum.” It’s got swing—it’s got jazz! See?

So it seems a little off. That’s why in all Chinese art, there’s not symmetry. There’s not complete balance between two sides of the painting, because the moment you have symmetry you have something static. But when you’re a little off, then it moves. So in that way, when vou study this architecture, you will see that it’s always a little off. It would be dead if two sides of a room were just the same. They’re always exploiting this! —Whoo, whoo, whoo, whoo, whoo.

Well now, you and they can understand this theoretically. If I say it in words, you can probably follow my meaning, and realize that all this is very true from a theoretical point of view. But what is much more important is, do we feel it to be so? Do we experience this relationship of man and nature to be as reliable and as true as we experience the ground under our feet, or the air coming into our lungs, or the light before our eyes? Because if we don’t experience it with that clarity, it’s not going to have any effective influence on our conduct. We’ll know theoretically that we are one body with the world. The world, you might say, is your extended body. But this won’t make any real difference to what you do, until you know it as surely, indeed more surely, than you know anything else. This amounts to a fundamental trans-formation of one’s own sensation of existence – of coming to be vividly aware, if I may say so: that you’re it!

As the Hindus say, Tat twam asi. You, or Thou art that. Only we feel much too guilty to agree with that. We feel that, uh, oh! that’s close to madness. There are people in lunatic asylums who say that they’re Jesus Christ, or that they’re God. But the trouble with them is, you see, they claim this for themselves alone. They don’t see that this claim goes also for anybody else. And the moment they stop making special claims, they feel lost, something crazy. But you see, if a Hindu or a Chinese person were to say, “Well, I’ve discovered that I’m God,” this wouldn’t have the same implications. People say to him rather, “Congratulations, at last you found out.” Because he has an idea of God, or of ultimate reality which is not exclusive, which is not something that sets itself up as a master technician that knows all the answers.

Well, let’s have a brief intermission.