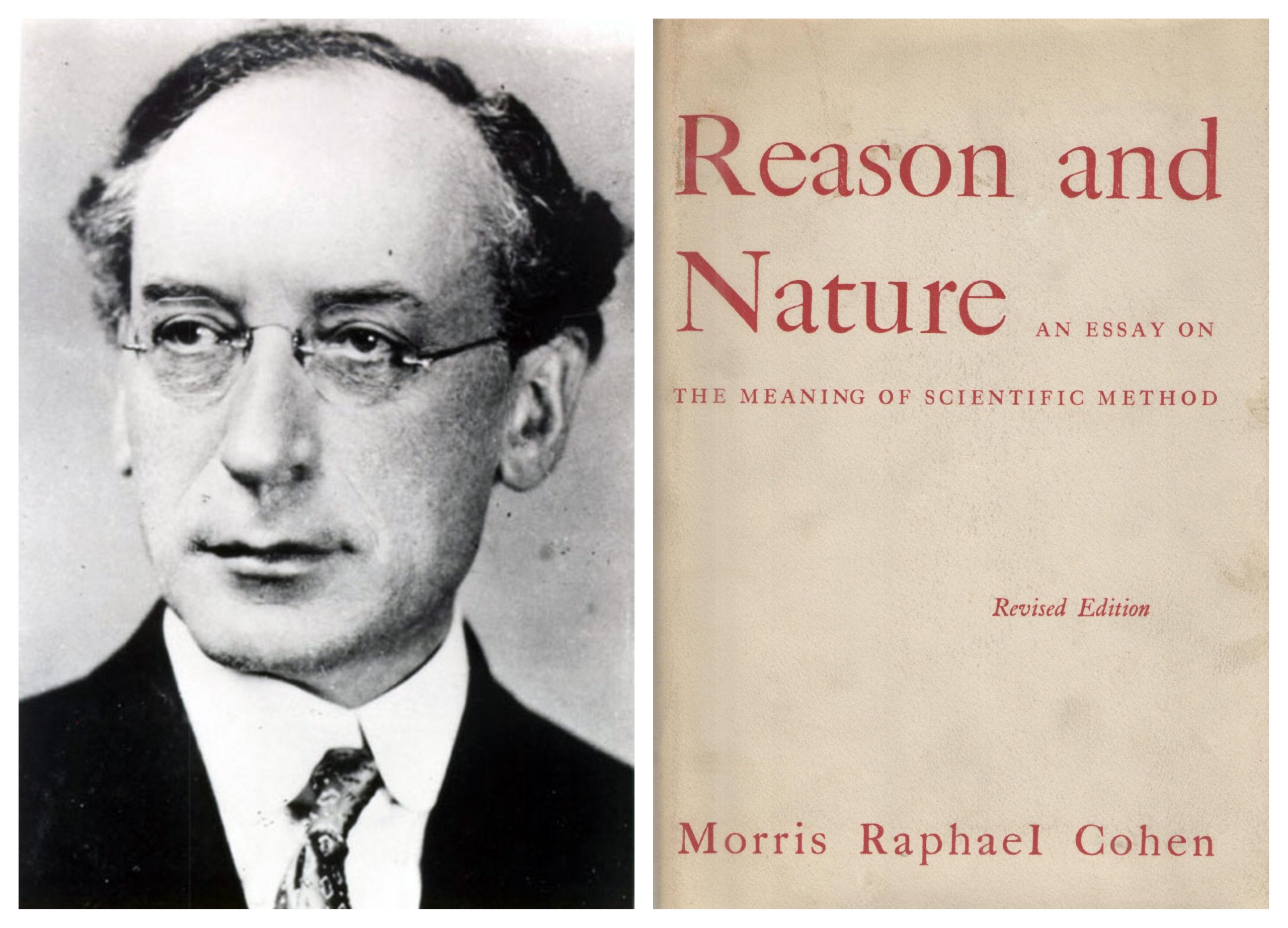

by Morris R. Cohen

Morris R. Cohen was born in Minsk, Russia, in 1880, and was brought to the United States at the age of twelve. Reared under many hardships on the New York East Side, he found means to educate himself at the College of the City of New York and at Harvard, attracting attention by his brilliancy of mind. For a decade he taught mathematics at City College. But his primary interest lay in philosophy and political science, and since 1912 he has held the chair of philosophy in that institution. Like John Locke, he deferred the publication of any important work until he was past fifty, imposing upon himself an arduous discipline in the mastery of many fields of thought and knowledge. But in 1931 he achieved an immediate reputation by his weighty treaties on Reason and Nature, and in 1932 enlarged it by his volume Law and the Social Order.

* * *

As law and justice concern large numbers of individuals living in relatively permanent groups, it has proved feasible for courts and jurists to elaborate some more or less definite techniques to answer certain of the questions involved. This, however, is not the case with the more subtle and elusive problems of personal life. Can science be applied to the whole art of living? It is easy to see that the problems of law themselves involve assumptions as to the ultimate good of human life, and ancient Semitic jurists suggested that he who would deal with the law must meditate on life and death.

We cannot, therefore, avoid the question whether there can be a science of ethics covering the whole field of human conduct. Let us, before considering more objective difficulties inherent in the conception of a moral science, review the more important of the human obstacles in the way of adopting a scientific attitude toward the values of life.

The difficulties of social science are intensified in the realm of morals. For moral judgments are deeply rooted in our habitual emotional attitudes and in those of the community of which we are a part. It is thus most difficult to detach ourselves from the roots of our accustomed faith, to question what seems obviously the right, and to devote the necessary patience and intellectual sympathy to the understanding of opposing views that we almost instinctively abhor and despise. This is true not only of the vast majority to whom the ways of respectability are unquestionable and decisive, but also of revolutionists in morals who move in groups that are inflexibly proud of being “up to date,” “emancipated,” “forward-looking,” “amoralist,” etc. I remember as a child having great difficulty in realizing that while the dome of heaven had its highest point directly over where I was, others living far off thought that the same was true for them. A similar realization in the moral realm is much more difficult.

Another difficulty in the way of attaining true views as to morals is the fear that these views will be perverted by the unintelligent or will have a bad effect on the young. Logically it might seem that if we believe new or heterodox views of morals to be true we should teach them to our children. But it is easier to change our theoretic views than our socially approved habitual attitudes. Thus many an agnostic sends his children to an orthodox Sunday school, and many confirmed Nietzschean amoralists are shocked when they hear their heterodox morality expressed before children. Some there are who justified this on the theory of vital lies, viz. that the young and the uneducated are not prepared for the truth and that we must keep them in check by convenient lies. Not many years ago a mother had no compunction about saying to her child: Don’t tell lies or the bogeyman will get you! But older children are still taught the falsehood that the virtuous will be (financially) prosperous and that the wicked will always be punished either by society or by their own guilty conscience. This disregard of truth in moral education is as old as Plato. Nevertheless I suspect that it prevails largely among those who have not attained full confidence in the truth of their own views. There are many stages between entertaining a heterodox view as to morals, and actually living according to it. And the extent to which a man lives up to a new moral insight depends on his personal situation and courage rather than on the truth of these insights.

Closely connected with the foregoing obstacle is the irrationality of moral theory resulting from the effort to give justifying reasons for the institutions which happen to exist. It is obvious that if the maxim What is, is right were true there would be nothing wrong in the world — not even with those who are always complaining of the evil in it — and all distinction between right and wrong would disappear as inapplicable or meaningless. Yet the fact that an institution exists gives arguments in its behalf an irrationally persuasive advantage over arguments against its value. We may illustrate this by a parable. Suppose that some magician came to us and offered us a magic carriage having great convenience, but demanded of us in return the sacrifice of thirty thousand lives every year. Most of us would be morally horrified by such an offer. Yet when the automobile is actually with us we can invent many ingenious arguments against the proposal to abolish it. Certainly an undue amount of moral philosophy is just an exercise in apologetics for what happen to be the prevailing moral institutions. Where the conclusion seems excellent we are not critical as to the supporting arguments.

Against the foregoing difficulties the moral philosopher must arm himself with the ethical neutrality of the scientist. Only by studying propositions about morals with the same detachment as propositions about electrons, caring more for the rules of the scientific game than for any particular result, can he hope to fulfill his function as a builder of sound ethical theory or science. How, indeed, can he promote the good life unless he first finds out what is the meaning of the good life and what are the conditions for attaining it?

In practice, the impetus to free scientific reflection on morality is greatly stimulated by familiarity with, and imaginatively living into, diverse moral systems. By taking note of moral variations, we may free ourselves from the absolute unreflective certainty which comes of not being able to imagine any possibility other than the one to which we are accustomed.

* * *

THE ILLUSIONS OE MORALITY

If with the ideal of scientific detachment in mind we approach the task of developing a rational ethics, we find two conflicting ways before us — the way of those who believe in absolute principles and the way of those who think that the needs of life are cruelly crushed by such principles. To explain the persistence of the two parties it is safe to assume that each has some part of the truth in its possession; but the fact of conflict is also presumptive evidence that each party is in the grip of some illusion which prevents it from seeing the whole truth.

1. The Illusions of Absolutism

Moral rules are most often viewed as absolute. It does not occur to most people that there can be any genuine doubt about them. Men generally are surprised and painfully shocked at the suggestion that we need to search for new moral truth or to revise the old. For the most part the absoluteness of these accepted rules is supported by some authority regarded as beyond question, e.g. by some priest, sacred book, or prevailing respectability. When, however, these or other authorities are in fact questioned, any attempted justification must involve an appeal to some “scheme of things entire,” of which these moral teachers form a consequence. Otherwise the moral teacher is in the position of the poor pedagogue who, when asked to explain or justify some questionable statement, stamps-his foot and shouts, “I tell you so.”

The sayings of great moral and religious teachers frequently find a magically responsive echo in our conscience. Yet our deepest moral feelings may seem to others no better than the superstitious taboos of primitive peoples appear to us. Indeed the morality of unreflective people does consist very largely of a series of taboos; you must not do so and so, and it is not proper to ask too insistently, “Why not?” Take one whom no one will lightly accuse of being unenlightened or irrational, to wit, Plato. The moral aversions which affect him most deeply are eating forbidden food (that is set aside for the gods) and incest. Yet not only the former but also the latter aversion depends upon accidental or external traditions. To Biblical heroes like Abraham and David, there seems nothing wrong in anyone’s marrying his sister by the same father, provided there are different mothers; and among the Egyptians and others, a marriage between brothers and sisters was considered rather honorable, at least in royalty. Many have shared Hamlet’s desperate horror of a man’s marrying his brother’s widow. Yet that was under certain conditions a pious command of the older Mosaic law.

When we are told that all civilized people are agreed about the immorality of murder, lying, theft, and adultery, we may well raise the doubt whether the agreement (of those who agree with us and are therefore called civilized) is not largely a linguistic phenomenon. We agree to use certain terms in a reprobative sense, but really differ as to what acts are to be so designated. There is certainly great diversity of opinion as to what acts we shall condemn as murder, lying, theft, and adultery.

Consider, for example, the commandment, Thou shalt not kill.

If this be viewed absolutely, should it not apply to the killing of animals as well as of humans? Anyone who has played with a dog (moralists are not reputed to be playful), or watched the gambols of lambs, knows how shocking can be the thought of killing them. The conventional argument that animals have not any reason like man need not be taken seriously. Are insane or idiotic men more rational than intelligent dogs? There seems to be no moral objection to killing a domestic pet to save it from suffering; why not justify euthanasia to relieve people of agonizing tortures?

Again, if the rule against killing be regarded as absolute, shall we not say that morally every heroic warrior is a murderer? If Thou shalt not kill be an absolute rule, how can it cease to be so because someone orders us to do it? “ God will send the bill to you.” Can we escape the difficulty by distinguishing between justifiable and unjustifiable wars, and say, for instance, that wars in defense of one’s country justify the taking of fife? Any such qualification obviously breaks down the absoluteness of our rule in making it depend on the somewhat shadowy distinction between offensive and defensive measures.

Furthermore, does the absoluteness of the rule, Thou shalt not kill, apply only to direct or short-range killing? We know perfectly well that unless more safety appliances are introduced into mines, railroads, and factories, tens of thousands of workers will surely be killed. Are those who have the power to make the changes and do not do so guilty of murder? If in economic competition I take away somebody’s bread (to increase my own comfort or power), and he dies of undernourishment or of a disease to which undernourishment makes him liable, am I not killing him? If by monopolizing bur fertile lands we confine the Chinese to a territory insufficient to keep them above the starvation fine, are we or are we not guilty of killing them?

To common sense and to many moralists nothing seems morally so self-evident as the sacredness of human life. Yet there seems good reason to question the rule that fife should always and everywhere be increased and prolonged, and that to restrict birth or hasten death is always and everywhere evil.

The sacredness of life is sometimes supported on supernatural grounds, viz. that since it comes from on high we have no right to meddle with it. We must not lay human hands on the gates of life and death. But this cannot possibly be carried out consistently. Disease comes from the same source as life and death; yet few now follow those moralists who denounced efforts to cure diseases sent by God to punish sinners. Does any moralist condemn the martyr who throws away his life to testify to his faith? We characterize as base those who purchase life at the expense of freedom, honor, or convictions. Not life as a biologic fact, but the good life (involving some coordinated plan or pattern) is the object of enlightened endeavor.

We arrive at the same result by considering the false naturalistic conception of self-preservation as a law of nature that leads everyone to seek always to preserve his own existence. In the chapter on biology we have had some indication of how misleading this phraseology is. But in the field of morals it is even less worthy of respect. Men generally have a positive preference or urge to live and want to postpone the pain of death. But they also want certain things for which they willingly shorten their lives by hard work, risks, etc. Of mere living existence we might soon get weary if it did not offer opportunity and hope of fulfilling some of the heart’s particular desires.

These doubts do not diminish the horror of murder in the cases where we feel that horror. But they are sufficient to suggest that the absoluteness of our rule is generally saved only by refusing to think of many of its possible applications to fife. The rule against murder does express a prevailing moral attitude in a number of clear though not explicitly qualified cases. It claims extension to cases similar in principle. In such extensions, however, we have to introduce so many sorts of qualifications that the rule soon ceases to be categoric and becomes rather dialectical: to the extent that any action involves the destruction of life it is to be condemned — but other principles may supply countervailing considerations. As any definite course of action involves many elements, actual judgment upon it must depend upon some estimate of the relative weights of diverse conflicting moral rules that can be applied to it. What we call a situation involving a conflict of duties is really a case in which different results would follow if we attended to one or another of rival dialectical rules.

A great and noteworthy effort was made by Kant to prove all moral rules absolutely obligatory and to derive them all from one principle, the categoric imperative to so act that the maxim of our acts can be made a principle of universal legislation. To one who asks, “Why should I accept this categorical imperative as the rule of my conduct? ” Kant offers no reason except to offer this principle as a formula for the unconditionally obligatory character of all moral rules, such as the absolute prohibition against lying. But why should I regard the latter as absolute? Why may not a lie to save a human being hovering between life and death be justified? There is no logical force at all in the claim that there is some absolute contradiction or inconsistency in telling a lie and wishing to be believed. Nor is there any force in the argument that lying is morally bad because it cannot be made universal. The familiar argument, “If everybody did so and so . . . ” applies just as well to baking bread, building houses, and the like. It is just as impossible for everybody to tell lies all the time as to bake bread all the time or to build houses all the time.

Empirically, of course, it is true that lying is subversive of that mutual confidence that is necessary to all social cooperation. And this justifies a general condemnation of lying — but not an absolute prohibition.

One of the consequences of the absolutistic conception of moral rules is the Stoic and Kantian contention that since the moral law demands that sin be punished, it is immoral to pardon any sinner. This appears in the contention that if we know the world is to be destroyed tomorrow we must see to it that the last murderer is executed, else we shall all perish with the blood of his victim on our heads. It shows itself in the orthodox theologic conception of a hell for most of God’s creatures; for if God forgave sinners (without an expiating blood sacrifice on His own part which these sinners must accept) He would transgress the moral law. It seems that we have here a glorified development of the primitive idea that honor demands the avenging of insults, and the greater the dignity of the one offended, the greater must be the vengeance.

A scientific ethics certainly cannot accept absolute moral rules of the character indicated by the foregoing examples.

2. The Illusions of Antinomianism

The perception of the variations and inconsistencies of our moral judgments has, since the days of the Greeks, led people to entertain the view that morality is nothing but a matter of opinion or convention. There are many forms of this attitude, of which we may consider: (1) moral anarchism, (2) dogmatic immoralism, and (3) antirational empiricism.

(1) Moral Anarchism. By moral anarchism I mean the view which denies that there are any moral rules at all, and insists that our moral judgments are mere opinions, having no support in the nature of things. In fact, however, no one of us believes that his own moral opinions are as bad or as absurd as those of others which fill us with repugnance or resentment. If, on the other hand, it is not true that every opinion is as good or as bad as any other, there must be some principle indicating the direction of preferable or more adequate judgment. We may not be always clearly aware of the principle involved in our actual judgments of approval or disapproval, and we may distrust abstract formulations of them, preferring to let tact or the feeling of the situation control us. But we cannot deny that such tact or intuition may involve serious error, and that such error might be corrected by fuller knowledge and reflection.

Skepticism is a natural reaction to the absurd claims of moral absolutism. It is justified in insisting that there is an arbitrary (in the sense of volitional) and indemonstrable assumption in every moral system, since we cannot have an ought in our conclusion unless there is an ought in one of our initial assumptions or premises. But from this it by no means follows that moral systems contain nothing but assumptions or that all assumptions are equally true or equally false.

(2) Amoralism. By the term amoralism I mean the attempt to deny validity to the distinctively moral point of view: to wit, that from which we judge that certain human acts ought or ought not to be. It is difficult to formulate without seeming self-contradiction a direct denial of any distinction between such seemingly different considerations as what is and what ought to be. However, there are many indirect denials of the validity of the moral point of view — by defining it in terms of the non-moral. The classical example of it is expressed by Plato’s Thrasymachus when he defines justice as the interest of the stronger. More recently this has been expressed in the formula: Justice is the command of the sovereign, the interest of the dominant class, etc. If this means that we, the weaker or the subjects, ought to obey the expressed command of one who has the power to’compel obedience, we have here a moral judgment, but of the kind that can rightly be called slave morality. For it is slavish to respect brute power, however prudent it may be to obey it, and the free intelligent man refuses to let mere external power confuse his vision of what is better.

Those who define justice or right exclusively in terms of some sort of might generally, however, wish to insist that judgments of right are in fact determined by certain external forces. But that is not a question of the meaning of the moral judgment but rather of its genesis. It is doubtless true that modern ruling classes do have some power directly or indirectly to mold the moral judgments of the community. But it would be folly to deny the fact that men can and do distinguish between that which they see prevailing about them and that which they think ought to prevail. The facts of moral indignation or the persistent and bitter cry for justice are too vehement to be easily ignored.

It is, of course, true that our moral aspiration can never be realized in this world unless we find an effective machinery for it, and this involves recognition and acceptance of the necessary concatenation between available causes and desired effects. It is thus in a sense true that only by submitting to nature can we control it. But this does not deny the distinction between what is and what is desirable.

Hegel and others have argued that individual judgments as to morality or what ought to be must be subordinated to the actually existing social institutions, on the ground that the latter embody a fuller and less capricious world reason. But while it is prudent for any individual to reflect and inform himself more fully before he condemns an existing social institution as immoral, an iniquity cannot cease to be judged an iniquity simply because it exists embodied in the Prussian or in any other state.

It is a significant indication of how far morality is popularly identified with conformity to the established order that Nietzsche calls himself and is called by others an immoralist. True, he attacks the moral value of Christianity, humility, and charity; but he himself is preaching a moral or categorical imperative: Act to obtain power regardless of ease and comfort. Despite his aversion for the Prussian state, this is a hard militaristic morality. Nietzsche’s illusion that power is an absolute good is indicative of the uncritical character of his thought. It is rather obvious that power can be exercised only in society. If isolated in a cave or on a mountain man has no power over his fellows and is more dependent on external nature. And a study of social power shows that rulership always involves a heavy sacrifice of freedom on the part of the ruler. Warriors and rulers have to give up their enjoyment and their life in fighting for the protection of their subjects; and in time of peace they may be ruled by priests who are distinguished by slavish obedience to the rules of their orders. In general, rulers are successful to the extent that they recognize the superior power of mass inertia, custom, religion, etc., and do not put themselves in opposition to such forces. The expert ruler must practice the art of flattery and cajolery or else be, like an Oriental despot, a slave to customary law and to the constant fear of losing his life. Stated more broadly, we may say that Nietzsche does not take into account the essentially social nature of man, i.e. his incompleteness by himself and his dependence on his fellow man. The love of power is one element of our nature, but the love of ease and comfort makes most of us shun the arduous labor, responsibility, and risks that are inevitable in the exercise of power. On the whole, government or rulership is possible because the vast majority find it easier to obey and thus be free from responsibility in all except some particular phase of life. The father may rule his children, who rule the mother, who rules the father. The scholar or artist may (and wisely so) care more for his learning or art than for the political governorship of his commonwealth.

There seem to be always moral protestants, who think that by merely breaking the traditional moral rules they will attain freedom and happiness. Alas for the irony of fate! In order to stand strong in each other’s esteem and to make up for the disapproval of the multitude, these moral non-conformists must develop a code of their own. The Bohemians of the Quartier Latin or Greenwich Village have their own taboos no less rigid than those of the Philistines.

(3) Anti-rational Empiricism. Anti-rational empiricism in ethics generally sets up the claims of what is called “the concrete facts of the situation” against all abstract rules. It refuses to subordinate the actual needs of life to preconceived tags. It rejects all Procrustean rules into which all men must fit themselves regardless of their diverse characters and changing circumstances. All this is a natural reaction to the illusion of absolutism. But it is equally illusory to suppose that a humanly desirable life can be lived without rules to regulate it or without the recognition of invariant laws or relations on which these rules must be based. Changing conditions are not inconsistent with the possibility and serviceableness of a rule of conduct, any more than physical changes preclude the possibility of an invariant law of constant elements or proportions. Against the claim that there can be no moral rules because no two situations are absolutely alike, we may urge that there could be no sort of intelligence as to life, no tact, intuition, or empirical wisdom of any sort, if there were nothing about any situation applicable to another. No two physical situations are ever absolutely identical. Yet this does not preclude the possibility of abstract physical laws that give us control over nature undreamed of by other means. In action as in science, not all that exists is relevant; and neither the fullness of life nor the fullness of knowledge can be attained without scientific organization which ignores or eliminates the irrelevant. What is chaos but a universe in which there is no order or law ruling out certain possibilities? The raving maniac’s mind, in which a piece of bread can become a burning volcano, or the ceiling a herd of elephants, points toward, though it falls short of, the absolute chaos in which all things are possible and anything may become anything else.

But if we cannot accept either absolutism or antinomianism, whither shall we turn?

Our previous analyses in the light of the principle of polarity of the issues between absolutism and empiricistic relativism provide a vantage point from which to see the truth at the basis of both contentions. Concretely every issue of life involves a choice. The absolutist is right in insisting that every such choice logically involves a principle of decision, and the empiricist is right in insisting on the primacy of the feeling or perception of the demands in the actual case before us. If it is possible for us to be mistaken in our moral judgments, there must be some ground for the distinction between the true and the false in this as in other fields. Even if we deny that principles are psychologically primary sources of moral truth and view them as only the formulas which give us abstract characteristics of our actual judgments in moral affairs, the errors of the latter can be corrected only by considering our judgments in similar cases, and this means cases alike in principle. Principles express the essence or form of a whole class of individual cases. And they enable us to correct the individual judgment precisely because the recognition of what is essential in many cases helps us to distinguish the relevant from the irrelevant in any one case.

The moral rules whose absolutistic claims we have rejected are useful generalizations of human experience, like the cruder generalizations of popular physics, e.g. that all bodies fall. The existence of exceptions to such generalizations proves that we must either refine their statement so that the exceptions will be included in the rule (just as the law of gravitation accounts for some bodies not falling) or else formulate our principles dialectically, as what would logically prevail if other principles did not offer countervailing considerations.

The imperfection of our generalizations makes the relativist underestimate their importance or reject them outright, while the absolutist falls into the logical error of confusing generalizations of experience subject to exception with truly universal or necessary propositions. We must, therefore, accept empiricism as to the content of moral rules without abandoning logical absolutism in our scientific procedure.

From Reason and Nature, copyright 1931 by Morris R. Cohen. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc.