PERSONAL HISTORY telling how the writer has lived with psoriasis, a skin ailment. It is a metabolic disorder that causes the epidermis, which normally replaces itself in the course of several days, to speed up the process and to produce excess skin cells. A tendency to it is inherited. The writer’s mother had it and her mother had it. The disease favors the fair, the dry-skinned. It keeps you thinking. Strategies of concealment ramify and self-examination is endless. Because of his skin problem writer chose a profession that did not demand being presentable. He married young because he found a comely & gracious female who forgave him his skin. They moved to Ipswich, Mass, because the town had a great beach. Baking in the sun on the beach relieved the skin symptoms. Tells about their life in Ipswich. In August, to escape local biting flies they left and rented a house in Martha’s Vineyard. In the winter he went to the Caribbean for the sun. Tells about these visits. In the fall of 1974 he left his wife and Ipswich. The next fall his skin was bad and he flew to St. Thomas but the sun did not help. At 42 he had worn out the sun. At this time a few blocks from where he was living in Boston, dermatologists at Mass. Gen. Hospital were developing the PUVA program to treat psoriasis. It was still in the experimental stage but he was accepted into the program. In a few months pills and artificial light did what salt water and sun could no longer do. His skin, was clear.

(NOTE: John Updike wrote a piece of fiction on this subject. It was “From the Journal of a Leper”, which ran October 19, 1976)

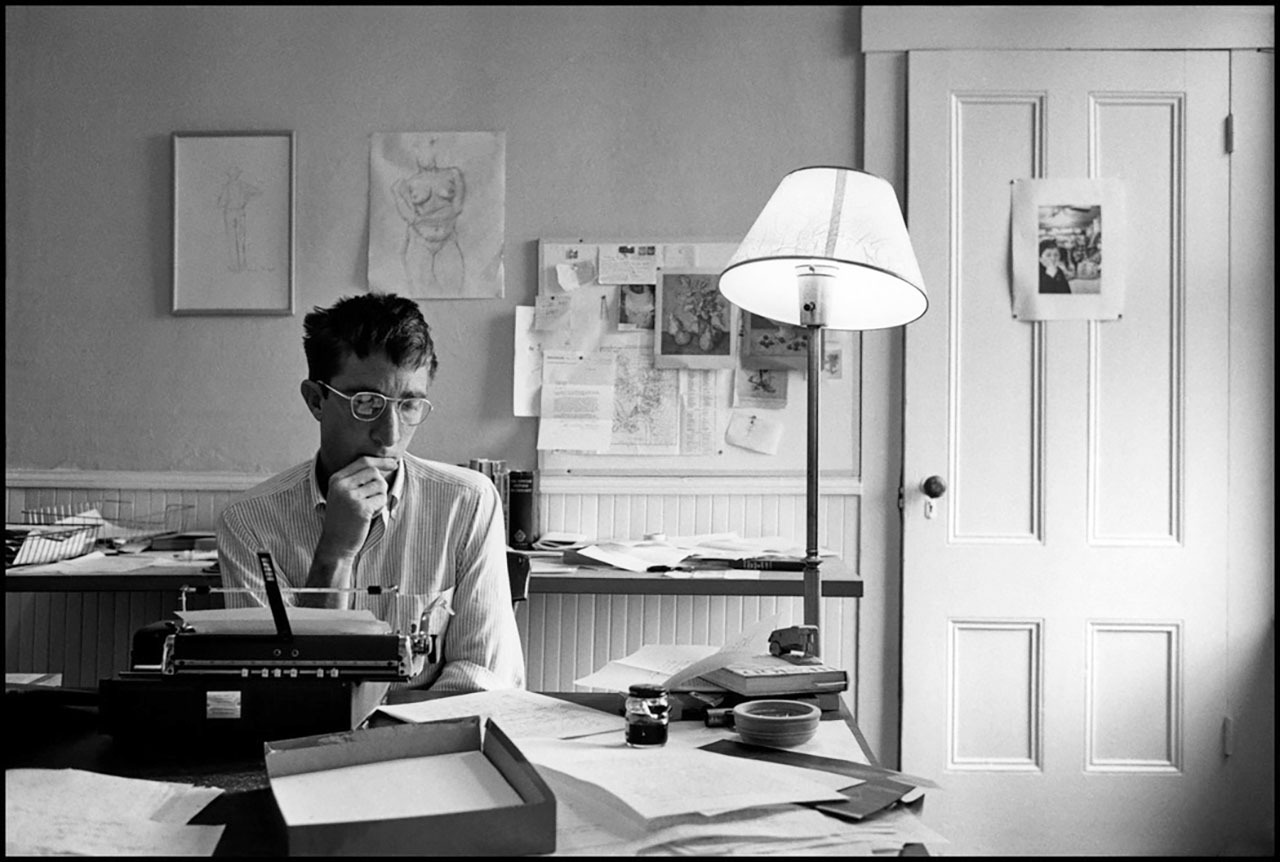

by John Updike

My mother tells me that up to the age of six I had no psoriasis; it came on strong after an attack of measles in February of 1938, when I was in kindergarten. The disease—“disease” seems strong, for a condition that is not contagious, painful, or debilitating; yet psoriasis has the volatility of a disease, the sense of another presence coöccupying your body and singling you out from the happy herds of healthy, normal mankind—first attached itself to my memory while I was lying on the upstairs side porch of the Shillington house, amid the sickly, oleaginous smell of Siroil, on fuzzy sun-warmed towels, with my mother, sunbathing. We are both, in my mental picture, not quite naked. She would have been still a youngish woman at the time, and I remember being embarrassed by something, but whether by our being together this way or simply by my skin is not clear in this mottled recollection. She, too, had psoriasis; I had inherited it from her. Siroil arid sunshine and not eating chocolate were our only weapons in our war against the red spots, ripening into silvery scabs, that invaded our skins in the winter. Siroil was the foremost medication available in the thirties and forties: a bottled preparation the consistency of pus, tar its effective ingredient and its drippy texture and bilious color and insinuating odor deeply involved with my embarrassment. Yet, as with our own private odors, those of sweat and earwax and even of excrement, there was also something satisfying about this scent, an intimate rankness that told me who I was.

One dabbed Siroil on; it softened the silvery scales but otherwise did very little good. Nor did abstaining from chocolate and “greasy” foods like potato chips and french fries do much visible good, though as with many palliations there was no knowing how much worse things would be otherwise. Only the sun, that living god, had real power over psoriasis; a few weeks of summer erased the spots from all of my responsive young skin that could be exposed—chest, legs, and face. Inspecting the many photographs taken of me as a child, including a set of me cavorting in a bathing suit in the back yard, I can see no trace of psoriasis. And I remember, when it rained, going out in a bathing suit with friends to play in the downpour and its warm puddles. Yet I didn’t learn to swim, because of my appearance; I stayed away from “the Porgy,” the dammed pond beyond the poorhouse, and from the public pool in West Reading, and the indoor pool at the Reading “Y,” where my father in winter coached the high-school swimming team. To the travails of my freshman year at Harvard was added the humiliation of learning at last to swim, with my spots and my hydrophobia, in a class of quite naked boys. Recently the chunky, mild-spoken man who taught that class over thirty years ago came up to me at a party and pleasantly identified himself; I could scarcely manage politeness, his face so sharply brought back that old suppressed rich mix of chlorine and fear and brave gasping and naked, naked shame.

Psoriasis is a metabolic disorder that causes the epidermis, which normally replaces itself at a gradual, unnoticeable rate, to speed up the process markedly and to produce excess skin cells. The tiny mechanisms gone awry are beyond the precise reach of internally taken medicine; a derivative of vitamin A, etretinate, and an anticancer drug, methotrexate, are effective but at the price of potential side-effects to the kidneys and liver more serious than the disease, which is, after all, superficial—too much, simply, of a good thing (skin). In the 1970s, dermatologists at Massachusetts General Hospital developed PUVA, a controlled light treatment: fluorescent tubes radiate long-wave ultraviolet (UV-A) onto skin sensitized by an internal dose of methoxsalen, a psoralen (the “P” of the acronym) derived from a weed, Ammi majus, which grows along the river Nile and whose sun-sensitizing qualities were known to the ancient Egyptians. So a curious primitivity, a savor of folk-medicine, clings to this new cure, a refinement of the old sun-cure.

It is pleasant, once or twice a week, to stand nearly naked in a kind of glowing telephone booth. It was pleasant to lie on the upstairs porch, hidden behind the jigsawed wooden balusters, and to feel the slanting sun warm the fuzzy towel while an occasional car or pack of children crackled by on Shilling Alley. One became conscious, lying there trying to read, of bird song, of distant shouts, of a whistle calling men back to work at the local textile factory which was rather enchantingly called the Fairy Silk Mill.

My condition forged a hidden link with things elemental—with the 4 seasons, with the sun, and with my mother. A tendency to psoriasis is inherited—only through the maternal line, it used to be thought. My mother’s mother had had it, I was told, though I never noticed anything wrong with my grandmother’s skin—just her false teeth, which slipped down while she was napping in her rocking chair. Far in the future, I would marry a young brunette with calm, smooth, deep-tanning skin and was to imagine that thus I had put an end to at least my particular avenue of genetic error. Alas, our fourth child inherited my complexion and, lightly in her late teens, psoriasis. The disease favors the fair, the dry-skinned, the pallid progeny of cloud-swaddled Holland and Ireland and Germany Though my father was not red-haired, his brother Arch was, and when I grew a beard, as my contribution to the revolutionary sixties, it came in reddish. And when I shaved it off, red spots had thrived underneath.

Psoriasis keeps you thinking. Strategies of concealment ramify and self-examination is endless. You are forced to the mirror, again and again; psoriasis compels narcissism, if we can suppose a Narcissus who did not like what he saw. In certain lights, your face looks passable; in slightly different other lights, not. Shaving mirrors and rearview mirrors in automobiles are merciless, whereas the smoky mirrors in airplane bathrooms are especially flattering and soothing: one’s face looks as tawny as a movie star’s. Flying back from the Caribbean, I used to admire my improved looks; years went by before I noticed that I looked equally good, in the lavatory glow, on the flight down. I cannot pass a reflecting surface on the street without glancing in, in hopes that I have somehow changed. Nature and the self, the great moieties of earthly existence, are each cloven in two by a fascinated ambivalence. One hates one’s abnormal, erupting skin but is led into a brooding, solicitous attention toward it. One hates the Nature that has imposed this affliction, but only this same Nature can be appealed to for erasure, for cure. Only Nature can forgive psoriasis; the sufferer in his self-contempt does not grant to other people this power. Perhaps the unease of my first memory has to do with my mother’s presence;! wished to be alone with the sun, the air, the distant noises, the possibility of my hideousness eventually going away.

I recall remarkably few occasions when I was challenged, in the brute world of childhood, about my skin. In the second grade, perhaps it was, the teacher, standing above our obedient rows, rummaged in my hair and said aloud, “Good heavens, child, what’s this on your head?” I can hear these words breaking into the air above me and see my mother’s face when, that afternoon, I recounted them to her, probably with tears; her eyes took on a fanatic glare and the next morning, like an arrow that had fixed her course, she went to the school to “have it out” with the teacher who had heightened her defective cub’s embarrassment. Our doctor, Doc Rothermel in his big grit-and-stucco house, also, eerily, had psoriasis; far from offering a cure out of his magical expanding black bag, he offered us the melancholy confession that he had felt prevented, by his scaly wrists, from rolling back his sleeves and becoming—his true ambition—a surgeon. “ ‘Physician, heal thyself,’ they’d say to me,” he said. I don’t, really, know how bad I looked, or how many conferences among adults secured a tactful silence from above. My peers (again, as I remember, which is a choosing to remember) either didn’t notice anything terrible about my skin or else neglected to comment upon it. Children are frank, as we know from the taunts and nicknames they fling at one another; but also they all feel imperfect and vulnerable, which works for mutual forbearance. In high school, my gym class knew how I looked in the locker room and shower. Once, a boy from a higher class came up to me with an exclamation of cheerful disgust, touched my arm, and asked if I had syphilis. But my classmates held their tongues, and expressed no fear of contagion.

I participated, in gym shorts and tank top, in the annual gym exhibitions. Indeed, as the-tallest of the lighter boys, I stood shakily on top of “Fats” Sterner’s shoulders to make the apex of our gymnastics pyramid. I braved it through, inwardly cringing, prisoner and victim of my skin. It was not really me, was the explanation I could riot shout out. Like an obese person (like good-natured Fats so sturdy under me, a human rock, his hands gripping my ankles while I fought the sensation that I was about to lurch forward and fly out over the heads of our assembled audience of admiring parents), and unlike someone with a withered arm, say, or a port-wine stain splashed across his neck and cheek, I could change—every summer I did become normal and, as it were, beautiful. An overvaluation of the normal went with my ailment, a certain idealization of everyone who was not, as I felt myself to be, a monster.

Because it came and went, I never settled in with my psoriasis, 8 never adopted it as, inevitably, part of myself. It was temporary and in a way illusionary, like my being poor, and obscure, and (once we moved to the farm) lonely—a spell that had been put upon me, a test, as in a fairy story or one of those divinely imposed ordeals in the Bible. “Where’s my public?” I used to ask my mother, coming back from the empty mailbox, by this joke conjuring a public out of the future.

My last public demonstration of my monstrosity, in a formal social setting, occurred the day of my examination for the draft, in the summer of 1955. A year in England, with no sun, had left my skin in bad shape, and the examining doctor took one glance up from his plywood table and wrote on my form, “4-F: Psoriasis.” At this point in my young life I had a job offer in New York, a wife, and an infant daughter, and was far from keen to devote two years to the national defense; I had never gone to summer camp, and pictured the Army as a big summer camp, with extra-rough bullies and extra-cold showers in the morning. My trepidation should be distinguished from political feelings; I had absolutely no doubts about my country’s need, from time to time, to fight, and its right to call me to service. So suddenly and emphatically excused, I felt relieved, guilty, and above all ashamed at being singled out; the naked American men around me had looked at my skin with surprise and now were impressed by the exemption it had won me. I had not foreseen this result; psoriasis would handicap no killing skills and, had I reported in another season, might have been nearly invisible. My wife, when I got back to my parents’ house with my news, was naturally delighted; but my mother, always independent in her moods, seemed saddened, as if she had laid an egg which, when candled by the government, had been pronounced rotten.

It pains me to write these pages. They are humiliating—“scabpicking,” to use a term sometimes leveled at modern autobiographical writers. I have written about psoriasis only twice before: I gave it to Peter Caldwell in The Centaur and to an anonymous, bumptious ceramicist in the short story “From the Journal of a Leper.” I expose it this third time only in order to proclaim the consoling possibility that whenever in my timid life I have shown some courage and originality it has been because of my skin. Because of my skin, I counted myself out of any of those jobs—salesman, teacher, financier, movie star—that demand being presentable. What did that leave? Becoming a craftsman of some sort, closeted and unseen—perhaps a cartoonist or a writer, a worker in ink who can hide himself and send out a surrogate presence, a signature that multiplies even while it conceals. Why did I marry so young? Because, having once found a comely female who forgave me my skin, I dared not risk losing her and trying to find another. Why did I have children so young? Because I wanted to surround myself with people who did not have psoriasis. Why, in 1957, did I leave New York and my nice employment there? Because my skin was bad in the urban shadows, and nothing, not even screwing a sunlamp bulb into the socket above my bathroom mirror, helped. Why did I move, with my family, all the way to Ipswich, Massachusetts? Because this ancient Puritan town happened to have one of the great beaches of the Northeast, in whose dunes I could, like a sin-soaked anchorite of old repairing to the desert, bake and cure myself.

The New Yorker, September 2, 1985