by Alfred Appel, Jr.

“If you want to make a movie out of my book, have one of these [criminal] faces gently melt into my own, while I look,” says Humbert Humbert (of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita), studying the “Wanted” posters in the post office. It seemed incredible to Nabokov in 1954 that such a film might be made, yet it is not surprising, if only for one reason. Nabokov is an intensely visual writer—”I see in images, not words,” he says—and his work abounds in images and scenes that are cinematic by design.

“Houses have crumbled in my memory as soundlessly as they did in the mute films of yore,” he writes in his memoir, Speak, Memory; but in Lolita he favors more sinister effects and an iconography which bring to mind more recent films. Describing his tormented first conjugal night with Lolita, Humbert recalls how, after all the hotel guests “were sound asleep, the avenue under the window of my insomnia, to the west of my wake—a staid, eminently residential, dignified alley of huge trees—degenerated into the despicable haunts of gigantic trucks roaring through the wet and windy night.”

Nabokov’s mise en scène, his prose equivalent of deep-focus, creates a veritable dark cinema here, for the most evocative aural and visual descriptions in Lolita are in the manner of classic Forties films noirs, with their oppressive rain-washed nightscapes and their desperate, driven men—seemingly decent people who have irreparably committed themselves to their dreams, passions, or obsessions, and are suddenly criminals, their respectable selves dissolved into the “Wanted” poster imagined by Humbert.

Humbert’s thin guise of bourgeois normality, links him with the central characters in several films noirs, particularly some of the non-gangster roles played by Edward G. Robinson. But Humbert’s affinities with noir characters are obvious enough, and any extended comparison would reveal differences as well as similarities; he is more a rhetorical than a visual figure. A comparison of film noir with the quotidian world of Lolita is far more rewarding because it provides a happy instance in which the accomplishments of high and popular art may be considered in the very same terms.

Because the film noir is not a genre, its properties cannot be defined as readily or exactly as those of, say, the Western. It is a kind of Hollywood film peculiar to the Forties and early Fifties, a genus in the gangster film thriller family. The taxonomic tag first introduced by French cinèastes of the Fifties is appropriately imprecise—film noir is a matter of manner, of mood, tone, and style—though its cultural attitudes are concrete enough, its psychological appeal quite direct.

Although the most memorable of early films noirs—Shadow Of A Doubt, Laura, The Woman in the Window, Double Indemnity—variously penetrate the masks of middle-class probity, many other films noirs are, in the outlines of their plots, indistinguishable from traditional gangster films or thrillers (thus the 1946 version of The Killers, and Gun Crazy). Scarlet Street, a domestic tragedy, and The Big Heat, ostensibly a big city crime and corruption melodrama, both directed by Fritz Lang, suggest that a capacity for betrayal and violence is human rather than “criminal,” and the expressive low-key lighting of the two films establishes a consistent tone.

What unites the seemingly disparate kinds of films noirs, then, is their dark visual style and their black vision of dispair, loneliness, and dread—a vision that touches an audience most intimately because it assures them that their suppressed impulses and fears are shared human responses. It is no wonder that these old movies “hold up” so well today, and that at least one young moviegoer of the Forties should have found them strangely comforting. Out of the Past is a title that encapsulates the elements of loss, nostalgia, and anxiety as common to the film noir as they are atypical of what Humbert terms the “grief-proof sphere” of Hollywood. Masked as genre entertainments, the finest films noirs are “escapist” works only in the sense that they consistently avoid and challenge the sentimentality, piety, and propaganda, the programmed innocence and optimism of most Hollywood films of the period.

The best and most influential film noir directors and technicians were German or Austrian refugees. Although F.W. Murnau and other directors susceptible to dollars had introduced the Germanic style in their Hollywood productions of the late Twenties, refugee directors such as Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak, Max Ophüls, Otto Preminger, and Curtis Bernhardt transformed the “look” of the American cinema of the Forties and early Fifties.* Happily enough, a good deal of their more Gothic baggage did not survive the move to Hollywood, and the blatant devices of Expressionism, which many of these directors had abandoned long before Hitler’s advent, persisted mainly in American horror films.

Characteristic of their films noirs is the more refined and poetic Stimmung (mood) of the German cinema, which utilized mannered lighting, rather than bizarre sets, to render the “vibrations of the soul.” The chiaroscuro of this Stimmung might seem to have been perfected in Thirties Hollywood by Sternberg’s famous cycle of Dietrich Films; but their campy charms were decidedly non-Germanic, and their exotic settings were the fantasias of their creator rather than a refraction of familiar American surroundings, the solidly located domain of even the most stylized films noirs of the refugee directors.

Nor is the chiaroscuro of the American films of these directors simply an indulgence of techniques left over from the heyday of the UFA studio. It is instead the cinematic expression of stark and sorrowful and pessimistic attitudes that had been confirmed if not heightened by the exigencies of their own historical circumstances. Often effected more elegantly than it had been in Germany (here, perhaps, the Sternberg influence), this melancholic visual style is also informed by a mordant eye for the kind of cultural details that had been overlooked by most native American directors. If some of their later American work would seem slack (Preminger), careless (Lang), or casually cynical (Wilder), it may well be because their films of the Forties and early Fifties had profited from the fact that they were the product of an artist’s exhilarated response to a radically new culture.

“I read a lot of newspapers [after my arrival in America], and I read comic strips—from which I learned a lot. I said to myself, if an audience—year in, year out—reads so many comic strips, there must be something interesting in them. And I found them very interesting. I got (and still get today) an insight into the American character, into American humour; and I learned slang. I drove around in the country and tried to speak with everybody. I spoke with every cab driver, every gas station attendant—and I looked at films.” The speaker might be Nabokov describing how he prepped for Lolita; actually, it is Fritz Lang, rehearsing his own Americanization.

That Lang and Nabokov should have responded so similarly to the lies and trivialities of the popular arts is surprising only if one believes that directors merely pander to their audience, that movies are incapable of criticizing mass culture. A movie screen is the ideal space on which to project such a critique. Although the studio-oriented Lang worked more quietly than the noir directors of the late Forties and early Fifties, who often filmed on location, his effects are sardonic enough, and truly subversive. “A Boy Scout is never scared.” says the scout to the newsreel camera in The Woman in the Window after he has discovered the body of the man whom Edward G. Robinson has murdered and dumped in the woods; Lang finds the chubby boy’s ethic less than amusing. And when a terrified Robinson turns on the radio to hear any news about the murder, he must endure an interminable “Castola Rex” laxative commercial.

An equally unbearable and grimly humorous tension is created in Scarlet Street. Hen-pecked Robinson, a frustrated painter, cowers while his monstrous wife listens to “The Happy Home Hour” or “Hilda’s Hope for Happiness,” her favorite soap opera. Robinson’s own hopes rest with Kitty (Joan Bennett), but her initial appearance in the film augurs poorly for their future. Clad in a transparent plastic raincoat, she is less a woman than a piece of packaged goods, though it is Robinson who will be consumed.

Throughout Scarlet Street, Kitty’s vulgarity is counterpointed by the soundtrack’s rendition of her favorite number, “Melancholy Baby.” The song, always a joke to musicians, is no romantic descant here; it underscores the dreariness of mass culture. Many films noirs use music in a similar fashion. A juke box dominates the opening and closing scenes of Preminger’s Fallen Angel, and the cheapness of waitress Linda Darnell’s dreams is defined by “Slowly,” the corny tune she continually demands. An animating if not animate object, that juke box is the cultural center of Preminger’s small town, and its contents and “gonadal glow” (to quote Humbert) are an incessant, oppressive presence in the films of the refugee directors; their soundtracks, frequently orchestrated by other recent arrivals from Europe, stress the cloying qualities of standard songs in a manner reminiscent of the Berlin musical caprices of Brecht and Weill.

“Always” is used ironically in Robert Siodmak’s black Christmas holiday, and a jarring rhumba arrangement of “Dark Eyes” is offered as Circe’s song in the nightclub scene of the same director’s criss cross. Projected by a distant radio, the eerie and haunting strains of ‘Tangerine,” the narcissist’s anthem (“Yes, she (Tangerine 1 has them all on the run’But her heart belongs to just one—Tangerine”), drift through the claustrophobic final scene of Wilder’s double indemnity as Fred MacMurray confronts, murders, and is himself mortally wounded by his double-crossing accomplice. Barbara Stanwyck.

Belles Dames sans any merci are a constant menace in films noirs. Ella Raines’ grotesquely “glamorous” get-up in Siodmak’s phantom lady, a burlesque of Hollywood “sexiness,” finds its musical equivalent in the cacophonous and uncontrolled jazz performed by Elisha Cook’s band, and the lovely melody of ‘Til Remember April” is linked with a murder. In touch of evil, directed by Orson Welles, the most Germanic of American stylists, rock ‘n’ roll is clearly Lucifer’s music. Played on the radio at top volume to cover-up a motel crime, its shattering decibel count is fitting because touch of evil is the culmination of film noir. Crises of society and self merge in the foreground of touch of evil, which was filmed in that graveyard of American aspirations. Venice, California—a tawdry and decaying remnant of an eccentric millionaire’s attempt to re-create architecturally Europe’s glorious past.

When the film noir went outdoors, its vision of America became more severe, a sci-fi forecast of the future, as dictated by the realities of Southern Californian locations. Doubtless everyone knows that almost every otherwise idyllic American community now has its own prototypical Southern Californian commercial street, with its motel or motor court, its discount stores and garish Da-Glo signs, its gas stations festooned with the competing banners of a price war, its glass and chrome quick-service lunch counters and its pseudo-ethnic eateries, unpalatable in every way, their bizarrely designed buildings topped by an enormous plastic pizza or sombrero. But not everyone knows the degree to which the film noir’s view of roadside America anticipates Lolita and the Black Humor Lolita would beget in the Sixties.

These films in turn have their literary precursors: Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust, and, more importantly, since their findings were less freakish, the hard-boiled California writers such as James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler (whose education and residence in England made him a kind of internal émigré when he returned home). Their unremitting and gloomy depiction of a commercial culture is especially telling inasmuch as their stories and novels were, like movies, offered as light genre entertainments, often enough in the pages of popular or pulp magazines such as Liberty and Black Mask. It is not surprising that several works by Cain and Chandler readily became excellent films noirs, though some literary critics, following Edmund Wilson’s lead in “The Boys in the Back Room” (1941), continue to hold this fact against the hard-boiled school.

Like West and, subsequently, Nabokov, Cain didn’t have to invent bizarre phenomena pictured in his novels. “The Victor Hugo,” described in Mildred Pierce as “one of the oldest and best of the Los Angeles restaurants,” is an actual place. And viewers who dismiss as an obscene invention the funeral of Gloria Swanson’s pet monkey in Wilder’s sunset boulevard have doubtless never visited the elaborate tombstones erected in Forest Lawn cemetery to commemorate the beloved pets of movie stars.

Witness the hard-edged visual style of Double Indemnity, one of the first films noirs to use actual Los Angeles locations. The furtive, initial rendezvous of Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray was filmed in Jerry’s Market on Melrose Avenue in Hollywood. The neat and antiseptic surroundings mirror the dispassionate manner in which they plot her husband’s murder. A close-up of Stanwyck, her eyes shrouded by dark glasses, positions her expressionless white face against a pyramid of baby food boxes, whose multiple cherubic images radiate the life that the childless woman would deny, reducing her to a flat image—a Pop Art Death’s Head. L.A. (as yet unpainted).

Surface authenticity resounds through films noirs from Double Indemnity through Touch of Evil. Its infernal or fallen world is ironically glossed by actual signs awaiting the arrival of Welles’ cameraman—”Hotel Ritz” (a run-down place), “Jesus Saves,” “Paradise.” A blind woman sits by a sign that announces, “If you are mean enough to steal from the blind Help Yourself.” “We Deliver” “More for Less” read the run-on twin signs on the rear wall of Jerry’s market, a happy accident that ironically frames the two lovers, whose murderous insurance swindle will cost them their lives.

Double Indemnity is perhaps the high point of the first period of noir. Directed by Billy Wilder and adapted by scenarists Raymond Chandler and Wilder from a short novel by James M. Cain, it is the result of a signal conjunction of talent. The film changes the novel considerably, and improves it by making MacMurray a less cynical and more Average American who is unwilling to kill, if only at first—one of several subtle shifts that draw upon the actor’s light-comedy screen persona and emphasize the viral nature of materialism.

“America was promises,” declared Archibald MacLeish in the Thirties, and the film noir records the erosion of the fabled open American road. A generation that has suffered through the Vietnam war, Watergate, and the ecological crisis quite rightly “reads” these films in the dark light of the moment. But meretriciousness and deceit did not yet appear to be the law of the land in 1954, when Lolita was completed, and Nabokov justifiably laments the way it “was welcomed, particularly by left-wing Europeans,” as an “anti-American book.”

Lolita’s tone is far too complicated for its attitudes to be reduced so flatly. Reviewing the itinerary of the twenty-seven thousand miles he spent on the road with Lolita in 1947-48, Humbert says, that “our long journey had only defiled with a sinuous trail of slime the lovely, trustful, dreamy, enormous country.” One could argue that Lolita belies Nabokov’s conscious intentions, yet the émigré novelist’s gratitude as well as his naturalist’s sense of wonder and beauty do shine through the narrator’s “satirical” observations.

The American continent in Lolita is not about to be consumed by hell-fire or sink into the slime of Judgment Day, as it is in The Day of the Locust and Touch of Evil; Nabokov’s contempt is aimed at the manipulators who would homogenize, despoil, or corrupt the “enormous country,” with its “trustful” inhabitants. Lolita personifies an innocence that was surrendered in advance of Humbert’s foul assaults. A “tender charm” nevertheless manages to linger about the “tragic” nymphet. a casebook victim of Pop culture whose youth has been claimed and denied by two armed forces. Although Nabokov may not share the extreme pessimism of the film noir, Lolita’s definitive indictment of a corrosive mass culture is very much in the spirit of film noir.

Humbert is no “underworlder” fan, yet his research-oriented creator seems to have absorbed something of the atmosphere and visual style of film noir and profited too from the example of its compact yet trenchant mises-en-scent. Nabokov doesn’t remember many film titles, but he does admire Murnau’s the last laugh—a wellspring of non style—and is not unaware of film noir, as I discovered inadvertently during a visit to Switzerland in November 1972.

Returning from a walk, Nabokov and I entered the dimly lit bar of the Montreux Palace Hotel. Standing at the bar, he ordered a scotch, and I asked for a well-known aperitif which was not in stock. “Good!” said Nabokov, “that’s no drink for a man.” Our rather tight-fitting overcoats still on, we began a three-way badinage with the barman on the unavailability of that aperitif. “We’re like Hemingway’s killers,” observed Nabokov, speaking out of the corner of his mouth in mock-gangster fashion.

Pointing to his wide-brimmed gray fedora, placed in gentlemanly fashion on a bar stool, Nabokov said, “I should return it to my head, no?, and heighten the realism. I loved ‘The Killers’ and the [initial] film version, too [1946, Siodmak]: the first scene in the diner was superb, each detail so exact, the unappetizing kitchen in which the killers, working with frightening dispatch, truss together those innocent men. The scene in which the fellow [Burt Lancaster] awaits his fate in a tawdry, shadowy rented room was excellent, too. But the remainder of the film added a good deal to Hemingway, didn’t it? Gangster stuff. . .[Nabokov grimaces). . .more conventional, but very well done. I did the screenplay of Lolita in order to guard it against such liberties. What did Hemingway think of them?”

According to his biographer, Carlos Baker, The Killers “was the first film from any of his work that Ernest could genuinely admire.” Its compelling noir , qualities seem literally to have overshadowed any objections to those considerable “liberties,” which are not entirely scorned by Nabokov, either, his grimace notwithstanding. The killing of Quilty parodies some of that “gangster stuff,” of course, but the death-dealing dark sedan which rushes through the black night of The Killers, one of several fateful vehicles in the film version, prefigures Humbert’s paranoid vision of an endless American road coursed relentlessly by an automotive “McFate,” a “Proteus of the highway.”

The commercial success of The Killers prompted its producer to advertise his Brute Force as a sequel, “MARK HELLINGER TELLS IT THE KILLERS WAY!” declared the pre-auteur lobby posters, which for once did not lie or exaggerate. Featuring the same actor (Lancaster) and directed by Jules Dassin, Brute Force is the most noir of all prison movies because it focuses on personal obsession as well as violent action.

To compare it with Lolita is more than a stab in the dark. Humbert, writing his “confession” in prison, describes how he returned alone to The Enchanted Hunters, the scene of the crime, three years after Lolita’s disappearance, five years after their stay there. Having given up all hopes of tracing her and her “kidnaper,” he tried to recapture the past in “autumnal Briceland.” Leafing through a “coffin-black volume” of the 1947 Briceland Gazette, he noted that Brute Force and Possessed were to come to the two Briceland theatres the week following his “honeymoon” sojourn with Lolita.

One would assume that Nabokov had culled these fitting titles from a newspaper ad or an uninviting theatre marquee. “No, no,” he says, “I saw both films, and thought them appropriate for several reasons. But I don’t remember why. . .so many years have passed. Was one a prison picture? I guess I should have said more about them.” Indeed yes.

John Milton was able to assume that his narrow seventeenth-century audience shared the same education and would “get” the classical and biblical allusions that now necessitate crowded footnotes. The modern writer, as opposed to unemployed scholiasts, is not so fortunate. Lolita’s most important literary allusions, to Poe and Carmen, can be recognized by a reasonably well-educated reader, but the meaning of more commonplace materials may be lost, since one generation’s popular culture is another’s esoterica.

Billy Wilder used only the melody of “Tangerine” in Double Indemnity, and the effect, a kind of aural shorthand, is more subtle than if he had allowed words; like Milton, he could assume that his audience knew the lyrics of a recent hit song. But Thomas Pynchon’s allusion to “Tangerine” in Gravity’s Rainbow, that massive Pop inversion of Milton’s method, is meaningless to anyone in Pynchon’s audience who hasn’t had the benefit of a democratic Forties education. Brute Force and Possessed are cases in point. Some of Lolita’s first readers (1955) may have remembered those 1947 films, but their functional thematic relevance is now as obscure as the storied background of one of Milton’s players.

Humbert, who cherishes the tattered photo of his lost Riviera love, has much in common with the prisoners of Brute Force, whose female cellmate is also an inanimate object, a pinup picture that provokes their own sexual fantasies. That it should be a composite portrait of the kind of actresses admired by Lolita is a fortuitous coincidence. Humbert’s dreams of vengeance upon Quilty never equal Brute Force‘s image of the stool pigeon being driven under a steam hammer by convicts wielding blowtorches, but that fate might well have entered Humbert’s terrible musings.

Possessed, an excellent film noir directed by refugee Curt Bernhardt, is more immediately appropriate. Joan Crawford plays a neurotic nurse whose hopeless and obsessive love for Van Heflin drives her into a loveless marriage with widower Raymond Massey. When Heflin pursues her new stepdaughter, Crawford slowly goes mad, has terrifying hallucinations, and finally murders Heflin. Discovered wandering about Los Angeles, she is institutionalized. The plot and chiaroscuro speak to the condition of Charlotte, destroyed by Humbert’s diary, and obviously apply to Humbert, too, who repairs to a madhouse a year after Lolita’s departure.

Brute Force and Possessed, the allusions that got away, are a small matter to be sure, yet they do underscore the problems occasioned by any allusive matter, high or low. It is safe to say that Lolita nevertheless survives, as does the analogy with film noir, buoyed perhaps by Nabokov’s remarks about The Killers. The acute observation of roadside America typified by The Killers and the Germanic Stimmung of film noir are everywhere in the novel, if not the film version.

That mood is, in a word, noir. Nabokov had employed German lighting tricks in a few scenes of Mary (1926), but the “endless night” of Humbert’s despair called for open-air nocturnal effects, and they are sustained in the best style of Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, They Live by Night, and other films noirs that were not fettered by the restrictions of indoor shooting. “She had entered my world.” says punster Humbert, “umber and black Humberland,” the shadowland of memory and desire.

Crucial scenes in Lolita are inevitably marked by rain, as in numerous films noirs of the period, which give the impression that a steady monsoon deluged America from 1944 to 1954 The seduction at The Enchanted Hunters occurs on a “soggy black night”; rain marks Humbert’s unhappy reunion with Dolly Schiller; and the thunderstorm which accompanies him to Quilty’s Pavor Manor heralds a downpour of effects which are “Germanic” in only the worst sense.

Humbert is as threatened and tormented by machines as he is by thunder: “And sometimes trains would cry in the monstrously hot and humid night with heartening and ominous plangency, mingling power and hysteria in one desperate scream”. The aura of “steam, smoke [and] infernal confusion” which Nabokov recalls so vividly from the train wreck in The Hands of Orlac also survives in films noirs such as Raoul Walsh’s White Heat, Brute Force (with its images of careening, enflamed vehicles), and the same director’s Thieves’ Highway. Dassin’s nightmarish visualization of the rampaging and roaring trucks combated by a weary driver (Richard Conte) might well be glossed by Humbert’s descriptions of his own fearful nocturnal locomotions or roadside insomnia: “At night, tall trucks studded with colored lights, like dreadful giant Christmas trees, loomed in the darkness and thundered by the belated little sedan.”

Along with The Americans (Robert Frank’s epochal book of documentary photographs) and Lolita, film noir established a contemporary iconography of the American road that forced its natives to see their environment with a new acuity. The concept of iconography, once the sole province of art historians stolidly limning the religious symbolism of Old Master paintings, has sometimes been applied rather loosely by cinéastes. Although the film noir tends to inspire open-ended definitions, it does possess a pattern of imagery recurrent enough to form an iconography as coherent and recognizable as the “underworlder” relics burlesqued in Clare Quilty’s death scene (cigars, guns, black clothes). The awe and respect with which Americans regard their cars surely warrants the grand designation “icon,” and the iconography of the car is central to Lolita, film noir, and The Americans.

Quilty’s tireless pursuit, his “cycle of persecution,” is made more harrowing by the constantly shifting rainbow profusion of his rented vehicles: Aztec Red, Campus Green, Horizon Blue, Surf Gray, Crest Blue, Chrysler’s Shell Gray, Chevrolet’s Thistle Gray, Dodge’s French Gray, and so forth. The car hues are very funny, but “I didn’t invent them,” says lepidopterist Nabokov, who cruised the country each summer in a series of secondhand cars chauffeured by his wife Vera. “I borrowed those colors from commercial manuals on cars obtained in Ithaca, New York, circa 1952.”

Humbert’s own car, a “Dream Blue Melmoth,” recalls many films noirs and the vagabond cars which serve as home and haven, death chamber or prison cell, all set in motion against the lonely landscapes of urban and rural America. In Out of the Past, for example, Robert Mitchum is never at rest or at ease, is never pictured in his house or apartment; where does he live?, one wonders. A car seems to be his sole possession, and it is there that he confesses his past to Virginia Huston (through flashbacks).

This setup is repeated in the final scene, femme fatale Jane Greer in Miss Huston’s place, the confessional booth transformed into a death cell; they both die violently inside the vehicle, lake the car in the opening sequence of The Big Heat or the glossy corpse-bearing Packard fished out of the water at the end of The Big Sleep, Mitchum’s car becomes a coffin.

The equation of cars with violence is obviously not new, but distinctions should be made, for the film noir did in fact expand and enrich the iconography established by the gangster films of the thirties. Except in Lang’s You Only Live Once, a precursor of They Live by Night and Bonnie and Clyde, the gangster’s car functioned in narrow, expected ways: as an arriviste gang lord’s “status symbol”; a chase or getaway car; an expedient place from which to fire a machine gun.

But film noir personalized that violence, removed those cars from a patently criminal ambience and serviced them in average filling stations, which made the fated action more immediate. By drawing upon wartime realities, film noir quite literally drove its dark themes homeward. A five-year moratorium on the production of cars had domesticated the American auto, had made it into a familiar worn figure, a member of the family whose own nutritional needs were also subjected to rationing. Post war car advertising, touting the millennial arrival of new models, took advantage of that famine, as did film noir.

After killing Quilty, Humbert drives across open country. “Since I had disregarded all laws of humanity. I might as well disregard the rules of traffic,” writes Humbert, explaining why he then crossed to the left side of the highway. “In a way, it was a very spiritual itch. Gently, dreamily, not exceeding twenty miles an hour, I drove on that queer mirror side… Cars coming towards me wobbled, swerved, and cried out in fear. . . . Then in front of me I saw two cars placing themselves in such a manner as to completely block my way. With a graceful movement I turned off the road, and after two or three big bounces, rode up a grassy slope, among surprised cows, and there I came to a gentle, rocking stop.” as helpless as a car-bound film noir hero victim.

The forward motion of the narrative has stopped, too—a conclusion analogous to the end of another mordant grand-tour of the country, Frank’s The Americans. Its closing image pictures a young woman and a boy, their faces blank from fatigue, huddled in the front seat of a cluttered car parked by the side of a bleak highway in Texas. “I was soon to be taken out of the car (Hi, Melmoth, thanks a lot, old fellow),” writes confessor Humbert, a more resilient traveler, who capers in prose for a putative judge and jury.

“And while I was waiting for them (the police and the ambulance people) to run up to me on the high slope, I evoked a last mirage of wonder and hopelessness,” another moment along the highway during which Humbert had realized the enormity of the loss suffered not by him but by Lolita. Eloquent and straightforward, in no way undercut by parody, the long passage represents a “mirror side” reversal of the reader’s assumption that the “spiritual itch” of morality is beyond Humbert. Released from his obsession by love, Humbert will be removed from Melmoth and transferred from his mobile cell to a real one, where he has already died of a coronary thrombosis.

Many films noirs are also narrated by dead or dying men (Laura, for example, Double Indemnity, or D. O. A., whose hero, Edmund O’Brien, has been slipped an antidote-proof poison), a narrative device which undercuts the old- fashioned idea of “story” by revealing its outcome. What remains is the unfolding of a terrible, fated action, the fleshing in of the outlines of human pain and panic.

Nabokov’s account of the novel’s origin, which may even be true, offers a moving and signal metaphor. “The first little throb of Lolita,” he writes in its Afterword, “went through me late in 1939 or early in 1940, in Paris, at a time when I was laid up with a severe attack of intercostal neuralgia. As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes [zoo] who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.”

Refugee Humbert, the “aging ape” writing from prison, whose impossible love figuratively connects him with that imprisoned animal, learns the language and records his “imprisonment,” and his book is the “picture” of the bars of the poor creature’s cage, visualized literally by a device borrowed from the cinema. Numerous directors and cinematographers have enjoyed the prison-bar chiaroscuro created by light projected through the slats of lattices or Venetian blinds. The device is far less blatant than even the best stills might suggest, since they are isolated, frozen moments of a moving picture.

Horizontal or oblique angles are favored because vertical shafts of light and shadow would be too obviously prisonlike. When they are employed dramatically and economically as a metaphor for entrapment or a clue that all is not well in the seemingly calm world of the film, the barred shadows are truly iconographic. If they are merely indulged to interrupt the visually boring surface of a wall, as in routine TV thrillers, the results will be interesting only to students of interior decoration.

Although it is impossible to say who first introduced this device, it is clearly present in the films of German (Wiene, Murnau) and “Germanic” (Stroheim, Hitchcock, Sternberg) directors of the Twenties and early Thirties. By the middle Forties it was omnipresent in American movies, the consistent signature of noir stylists in the wake of Murnau.

The Last Laugh records the decline of an old man (Jannings) whose identity is dependent upon his “status” as a Prussian-style doorman at a Berlin grand hotel. Unable to unload heavy trunks with his former aplomb, Jannings is stripped of his rank and demoted to washroom attendant; a heavy noir rainfall has augured his fall. The film was supposed to end with Jannings slumped in his mirror-lined cell, a condemned man sealed off by the striped shadows of a debilitating humiliation. (The subsequent epilogue, a “happy ending” foisted on the film by its producer, is as unconvincing as similar gratuities in Twain and Dickens.)

Sternberg’s Shanghai Express, starring Dietrich as Shanghai Lily (“the white flower of the Chinese coast”), sustains Murnau’s expressive visual. The shimmering bars of light that transform the corridor of the train into another prison cell are a visual correlative for the femme fatale’s spell and the various deceptions that lock each character into himself. Nabokov greatly admires “the wonderful stylized chiaroscuro” of these two films, and his is not empty praise. The most illuminating iconography of The Last Laugh and Shanghai Express, a dominant presence in film noir, also flickers from the pages of Lolita.

Humbert’s first night with Lolita contains vintage noir footage:

“The door of the lighted bathroom stood ajar; in addition to that, a skeleton glow came through the Venetian blind from the outside arclights; these intercrossed rays penetrated the darkness of the bedroom and revealed the following situation.

“Clothed in one of her old nightgowns, my Lolita lay on her side with her back to me, in the middle of the bed. Her lightly veiled body and bare limbs formed a Z. She had put both pillows under her dark tousled head; a band of pale light crossed her top vertebrae.

“I seemed to have shed my clothes and slipped into pajamas with the kind of fantastic instantaneousness which is implied when in a cinematographic scene the process of changing is cut; and I had already placed my knee on the edge of the bed when Lolita turned her head and stared at me through the striped shadows.”

She had wanted to go to the movies that evening, a request realized ironically by the unreeling of the “seduction scene,” with its baroque non mirrors and “striped shadows,” its campy horror-film close-ups (“my tentacles moved towards her again,” and so forth). Nabokov’s camera follows Humbert to and from the bathroom: “I re-entered the strange pale-striped fastness where Lolita’s old and new clothes reclined in various attitudes of enchantment.” As bewitching as anything worn or shed by Shanghai Lily, they are also a convict’s clothes.

Toward the end of the novel, Humbert recalls some “fabulous, insane [sexual] exertions that [had] left me limp and azure-barred” from the silvery neon lights outside their room (p. 287). This cinematographic effect, which looks back to The Enchanted Hunters, suggests the extent to which Humbert is imprisoned in “the pale-striped fastness” of obsession.

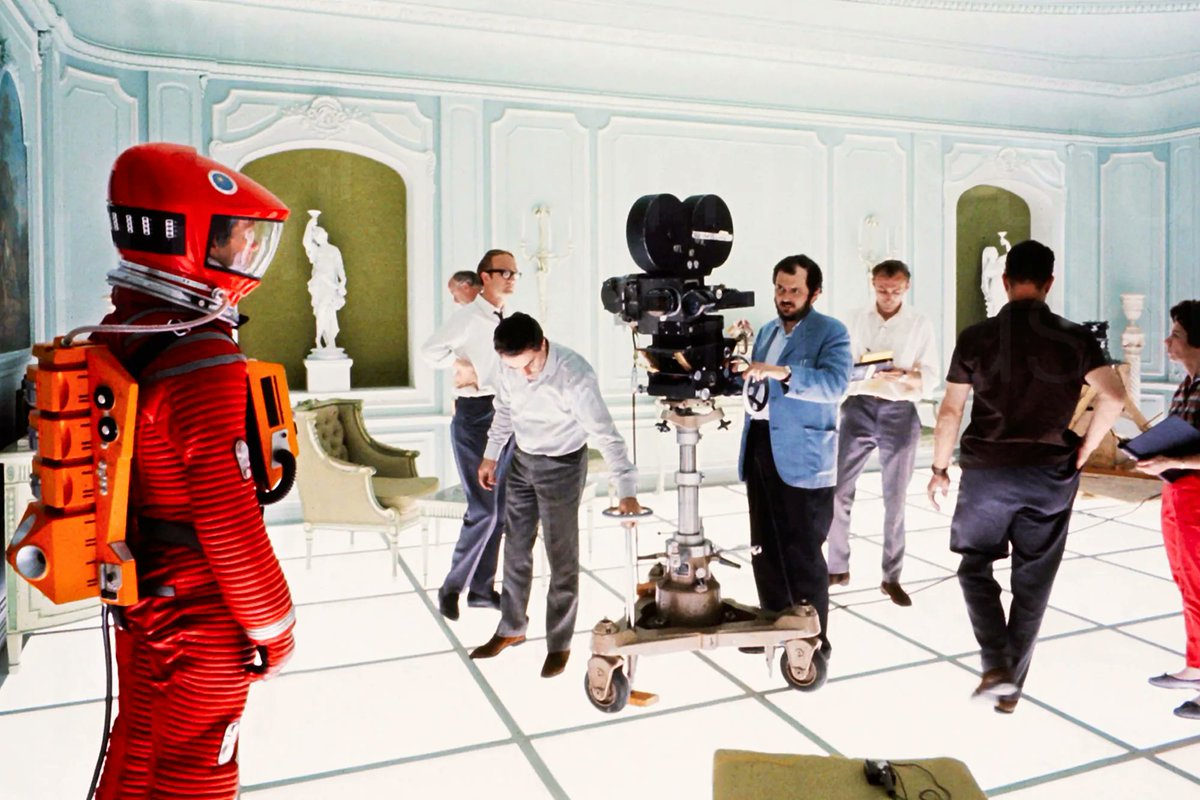

Stanley Kubrick’s version of the seduction scene is faithful to Nabokov*s film noir visuals, and the movie’s opening close-up of Humbert painting Lo’s toenails, repeated in a subsequent scene, is also noir enough. A direct allusion to the same ritual of enslavement as managed by Fritz Lang in Scarlet Street, it at first seems to suggest by way of hommage that Kubrick’s Lolita will self-consciously attempt the definitive film noir. Although Kubrick improved upon Nabokov by having Charlotte die in the rain, a very noir scene, the most curious and disappointing aspect of his Lolita is that it finally chooses not to follow the main roads traversed by film noir.

Note:

* Hitchcock’s English birth dooms him to a footnote, but he would reassert the Germanic style of his English thrillers of the Thirties in his American noir masterpieces, Shadow of a Doubt and Strangers on a Train. The sharp eye of the expatriate is exercised in the former film, which also gave scenarist Thornton Wilder a chance to view Our Town from a different, less sunny perspective.

Alfred Appel, recently immortalized with a news-break in The New Yorker, is Associated Professor of English at Northwestern University. This article is excerpted from Dark Cinema, to be published this fall by Oxford University Press.

Source: Film Comment, Vol. 10, No. 5 (September-October 1974), pp. 25-31