by Diane Jacobs

Critics have traditionally felt uneasy with anything that might be construed as intellectualism in the American cinema. So it is no surprise that even as astute a critic as Michael Wood should chortle a bit at Francis Ford Coppola’s bald allusions to “The Hollow Men” in Colonel Kurtz’s weird Cambodian haven in the final scenes of Apocalypse Now (1979). (T. S. Eliot himself is rarely chided for excerpting Conrad’s “Mistah Kurtz—he dead” for his poem’s epigraph.) “I would like to think Kurtz is drawn to this poem by Coppola’s sense of humor,” writes Wood in the New York Review of Books. “… But I am afraid the attraction is purely pedantry.”1

There is a touch of not unpleasing pedantry and seductive virtuosity to Apocalypse Now, as there is to its uncredited source, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902). Still, the issue is not Coppola’s literariness, but whether his borrowing from Eliot and more especially from Conrad are decorative or organic. What relevance has Conrad’s Victorian allegory to Coppola’s contemporary vision of soldiers water-skiing through combat zones, of sailors shooting heroin, of officers sniffing napalm for the scent of victory, and of the sort of gnarled genius who would think to sever the recently innoculated arms of enemy children?

Coppola himself broached this issue of decoration versus substance when discussing his more abstracted film The Conversation (1974). Because he could not identify with his protagonist, Coppola told Brian De Palma, he decided to “enrich”2 him: to embellish the wiretapper Harry Caul with his own childhood polio, his love for music, his Catholicism, etc. Unfortunately, that “enrichment” shows, and despite a nuanced performance by Gene Hackman, Harry remains a skein of quirks and obsessions. He plays the saxophone, suffers a pesky guilt, and clings tenaciously to his privacy. These details add up to a fascinating concept, but the character and ultimately the film itself lack sinew.

A number of critics insist that a similar esthetic decoration is at work in Apocalypse Now, that Heart of Darkness is little more than “enrichment,” neatly appended to John Milius’s genre script and no more essential to the film than polio is to Harry. To my mind, this is not the case: Heart of Darkness is the spine of Apocalypse Now. The film succeeds as an updated interpretation of Conrad because author and filmmaker share uncannily similar goals; because Coppola’s thoughts on American involvement in Vietnam and on power and the compulsion to vanquish the enemy are compatible with Conrad’s thoughts on avarice and colonialism, with its “strange commingling of desire and hate”3; because Marlow’s up-river journey, in the novel, to the “horror” of colonial Africa is a fittingly ironic paradigm for Captain Willard’s (Martin Sheen’s) penetration of Asia; because Mr. Kurtz’s lust for something beyond ivory is a fitting correlative for Colonel Kurtz’s yen for the ineffable beyond victory; and, finally, because Marlon Brando’s murky, corpulent, “unsound” Kurtz is very much Conrad’s Kurtz: a superior individual “on the threshold of great things,” “exalted,” and not just “hollow at the core” but unreal and sometimes unbelievable. There is a crucial difference between the novel and the film, but more on this later.

Like the novel, the film opens with its narrator anxiously awaiting a mission. Captain Willard prowls his Saigon hotel room, gulping booze, muttering about how uncomfortable he felt on his leave at home, and finally splintering a mirror with his fist and bloodying himself. When two men usher him off to receive orders for a top-secret mission, Willard’s reaction could he summed up in Marlow’s pre-existential musing: “I don’t like work,— no man does—but I like what is in the work—the chance to find yourself. Your own reality—for yourself, not for others. . . .”

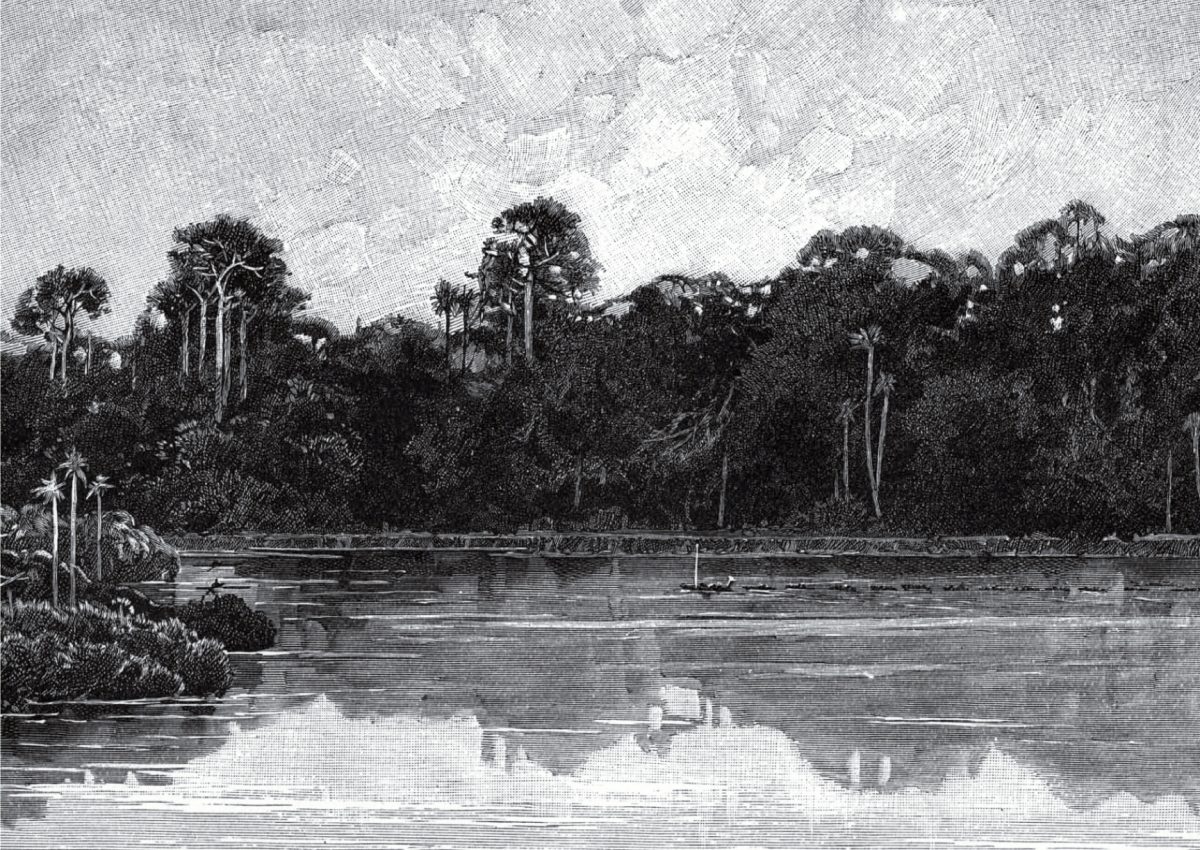

Marlow is a seaman, Willard an intelligence officer. Marlow, in the employ of a Belgian trading company in colonial Africa, sets off up the Congo to discover what has happened to one of his predecessors, the legendarily successful ivory trader, Mr. Kurtz. Willard, in the employ of the government, sets off not only to find but to kill his Kurtz, the Army’s erstwhile favorite son Colonel Kurtz, who has taken the war effort into his own hands. Against orders, Kurtz has crossed the Cambodian border and (like his Congo counterpart) has set himself up as a god/king to the willing natives. As a commanding officer points out to Willard, “what Lincoln calls ‘the better angel of our nature’ ” has lost out in the battle for Kurtz’s soul.

Like Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse Now is on one level an adventure tale. Conrad sends Marlow off to do battle with inclement weather, unfriendly geography, cannibals, inefficient Europeans, and unsympathetic natives with deadly weapons. Coppola dispatches Willard on a mission that will pit him against the NLF, tigers, and routine carnage as well as his “choice of nightmares”(p. 89).

Yet very little actually happens, either to Marlow or to Willard. They wait, and they watch. Marlow waits for a mission, and, once he has it, observes the coast of Africa (“smiling, frowning, inviting, grand, mean, insipid or savage and always mute with an air of whispering, come and find out”) from the deck of a French steamer (p. 19). Arriving at his company’s Central Station, he discovers his boat sunk and wrecked and waits for the rivets with which to mend it. By the time he encounters Kurtz, the novel is nearly two-thirds finished: Marlow’s intellect has digested the quiddities of Africa and the human soul, and he has done almost nothing.

Similarly, Willard anticipates and endures and, most importantly, scrutinizes: a helicopter attack, the ravaging of a village, playboy bunnies teasing the sex-starved troops, a bridge reconstructed every day to be demolished nightly. He observes carefully, but only rarely—when he shoots a Vietnamese woman, for instance—is he called upon to participate or to make decisions.

Coppola’s “heart of darkness,” like Conrad’s, is a triumph of style over story. Or rather, the description—words for Conrad, mise-en-scène for Coppola—is the story’s raison d’être. Marlow confronts the particulars of Africa in order to expatiate on the “flabby, pretending, weak-eyed devil of a rapacious and pitiless folly” (p. 23), or to explore “the fascination of the abomination” (p. 9). Marlow is not really concerned with rivets. The rivets are so diaphanously a pretext for him to ruminate on man’s relation to work that he never bothers to inform us where the rivets ultimately came from. One moment he is stuck, the next he is on his way, with no explanations offered.

The day-to-day, arduous reality of combat is equally irrelevant to Coppola, who is no more concerned with the little man in the trench than Conrad is with rivets. He is out to forge a vision of War, of the Vietnam War, and—less convincingly—of related horrors through dense, multilayered cinematography (by Vittorio Stovaro) and sound (by Walter Munch).

Neither Conrad nor Coppola really succeeds in fathoming “the horror” because neither succeeds in rendering Kurtz palpable. Conrad describes him as “very little more than a voice” (p. 69) and his “horror as “the strange commingling of desire and hate” (p. 101). But what, after all, is this? For Coppola, “the horror” is a similarly elliptical distance between superiority and madness. Like Conrad, Coppola is at his best when circling that horror, when presenting it a few rungs down on a recognizable, pedestrian level. Thus, Apocalypse Now is most effective when describing not Kurtz himself but the world surrounding him.

Like Conrad’s language, Coppola’s mise-en-scène at once batters and soothes. While the Dolby sound whooshes at us from myriad speakers, the limpid images attract us with their sensual beauty and repel us with their content. Similarly, the cinematography renders us both victim and perpetrator of numerous horrors. In the film’s most spectacular scene, for instance, we watch Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) and his fire-spitting helicopters swoop down from the skies as if we were the bewildered Vietnamese on the ground. Kilgore has ordered that his tapes of “The Ride of the Valkyries” be played, and the Wagner meshing with the helicopter descent and the splaying of bomb fire is ah once terrifying and absurd—clearly a lesser Conradian “nightmare.” But in the next shot, the tables are suddently turned. Now, the camera places us in the plane with Kilgore and directly behind the helicopter controls, thus affording us the arrogant, shameful exhilaration of power—yet another “nightmare.”

Contrary to much critical opinion, Apocalypse Now gets into trouble not in its allegiance to Conrad, but when it veers away from the book s assumptions. Indeed, the one serious problem with this often brilliant film is the character of Willard. Like Harry Caul and unlike Marlow, Willard is too idiosyncratic, too much the unknown variable to sustain the complexities of the work we perceive through his eyes. He is not an Everyman to Apocalypse Now the way that Marlow is to Heart of Darkness.

We can identify with many of Willard s traits and impulses. He is an efficient officer, for instance, and his judgments on such matters as Kilgore’s bizarre helicopter descent—”If that’s how Kilgore fought the war, I began to wonder what they had against Kurtz”— would surely be ours and Marlow’s. But in other respects, Willard is inscrutable and perhaps malevolent, for example when he abruptly kills a Vietnamese woman in order to get on with his up-river journey. Willard’s companion has capriciously wounded the woman for the sin of harboring a small dog in her boat. She is badly injured and in pain, and she will almost certainly die; yet, if given proper medical care, she might possibly live. To his credit, Willard will not have the woman suffer, but neither will he deflect his mission in order to find her a proper doctor. Shooting her is a half-merciful, half-murderous compromise.

It is useful to compare Willard’s reaction to the woman with Marlow’s response to the “too fleshy” man with the “exasperating habit of fainting” who accompanies him on a two-hundred-mile hike through thickets and ravines. Clearly, he is a bungling albatross, and Marlow admits as much: “Annoying, you know, to hold your coat like a parasol over a man’s head while he is coming-to” (p. 29). Still, hold that coat he does. Marlow is a moral quantity we know; Willard is an enigma.

As a rule, there is no reason to cavil about the idiosyncratic protagonist, but Apocalypse Now, like Heart of Darkness, demands a narrator we can trust. Coppola is flirting with myth, not debunking it (as Altman was, for instance, in his irreverent adaptation of Chandler’s The Long Goodbye). He is dealing with characters who are larger and situations that are, on the whole, more sweeping and less delineated than life. To lead us through this mythic world and, more importantly, to render that world credible, he needs a guide whose quirks we recognize and understand. We need someone to make sense of bridges that are destroyed every night and rebuilt each dawn to keep up the appearance of an open waterway. We need a sensibility capable of observing the particular lunacy of soldiers ordered to surf while a town explodes around them and to take that lunacy a step further. Willard is not quite that man. He is too shifty, too reticent with his ideas. Thus the horror he glimpses not only in Kurtz, but in himself, is not as universal as Marlow’s, and the film is not as powerful as it might have been.

Despite this weakness, Apocalypse Now is the most successful interpretation of Conrad to date. While its flaws are numerous, Coppola has achieved a felicitous welding of literary structure and genre subject: no mean accomplishment.

Notes

1. Wood, Michael, “Apocalypse Now”, New York Review of Books, October 11, 1979, Volume XXVI.

2. De Palma, Brian, “The Making of The Conversation”. Filmmakers Newsletter, May 1974, Volume 7, number 7.

3. Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness 1902 (rpt. London: Penguin, 1975), p. 101.

The English Novel and the Movies, pp. 211-217