by Michael Klein

If you would see the horizon from a forest, you must first build a tower… Of course the tower is crooked, and the telescopes warped… What supports our use of them, now, is that our intimacy with the master-builder of the tower… has given some advantage for correcting the error of his instruments.

Norman Mailer, The Armies of the Night

Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) presents a very different vision of the Vietnam War, one with enhanced perspective. While in general critics have been quite favorable to well-made films in the new war genre—Platoon and Hamburger Hill (1987)—their evaluation of Kubrick’s important work has been tempered by political sniping. For example, Philip French, in the 13 September issue of the British publication Observer, concludes that viewers of the film “receive our regular, liberal anti-war inoculation.” Pauline Kael, writing in an August 1987 issue of the New Yorker, contrasts Hamburger Hill and Full Metal Jacket. Hamburger Hill merits praise as a good example of the buddy combat film genre: “They fight because their country tells them to fight… and the movie respects their loyalty to each other.” This is in contrast to “the neat parcel of guilt supplied by Full Metal Jacket When critics, writing in somewhat establishment periodicals, adopt a patronizing tone, dismissing the political stance of a film as a matter of bad taste, often as “simply liberal” or “too neat,” I often take it as a sign that something interesting is happening in the work.

In general, praise of the technical brilliance of Full Metal Jacket has also been tempered by criticism of the film as being too “cold.” Critics tend to like the first section of the film (Kubrick’s savage parody of the brutality of boot camp military indoctrination) but feel uneasy about the second half of the film (his portrait of the disintegration of the American war machine in combat). In the first section of the film our sympathies are directed against a brutal, middle-aged, and extremely unattractive right-wing drill sergeant, a figure few in the audience would identify with. But in the second section of the film the war machine that the sergeant molded in the confines of a training camp at home in America is demystified: when tested in battle in Vietnam the recruits are panic-stricken, ill-disciplined, and decidedly unheroic. What makes some critics and spectators in the audience uncomfortable is that Kubrick inverts the combat film genre of Platoon and Hamburger Hill, in the process critiquing the chauvinism—both national and male—that often negates or undermines the antiwar stance of explicitly critical Vietnam films. The emotional distance of the film and its departures from naturalistic presentation of the war enhance the film’s critique. Invoking Brecht’s “alienation” effect (the formal distanciation and self-reflexivity he calls Verfremdung, or “strange-making”), Full Metal Jacket elicits the kind of multilayered dialectical reception Brecht called “complex seeing,” as it guides its audience to contextualize, to look at the specifics in the locus of the narrative in relation to larger questions on the intellectual horizon.

For example, let us review several key scenes in Full Metal Jacket. Early in the Vietnam section of the film, when the new marine division is being flown into battle in a helicopter, we witness an incident of genocide: an air cavalry machine-gunner, dressed in a flamboyant Hawaiian sport shirt, casually leans out of the helicopter and fires at civilians scurrying to cover on the ground below. Corporal Joker, our protagonist in the film, asks: “How can you shoot women, children…” The machine-gunner replies: “Easy—you just don’t lead them so much.” He laughs and then adds: “Ain’t war hell.” We have encountered similar “war is hell” statements before in combat films that claim to be critiques of the war effort: in the midst of Vietnam War sequences that affirm the tragic vitality of American servicemen in battle while denying Vietnamese any significant human presence. Kubrick’s parody is a chilling indictment of the complacent Cold War liberalism of that kind of film, for he is saying that unless we adopt another perspective we are no more than helicopter machine-gunners who have suffered or, in retrospect, have regrets. Thus it is significant that he begins the film with an extended inquiry into how the consciousness of the helicopter gunner was created.

The opening section or prologue of Full Metal Jacket is set in a marine boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina. Kubrick records in great detail the process of training a recruit to be a member of an elite corps of the U.S. fighting forces. However, this section of the film is far more than simply a critique of the sadistic and dehumanizing process of training that strips young men of their identities and shapes them into robotlike killing machines. U.S. military policy in the Vietnam land war was based upon a draconian strategy of counterinsurgency: search and destroy missions; free-fire zones; destruction of the countryside and/or of the NLF’s base areas; attainment of kill quotas. This strategy necessitated the production of a special kind of soldier, one who would not relate to potential objects of genocide (male or female) as fellow human beings. This in turn required the production of soldiers inculcated with conceptions of national and racial superiority and the inferiority of Third World peoples and with a warriorlike conception of masculine misogyny committed to rooting out the other-directed—that is “female”—aspects of their personality. Kubrick illustrates that these qualities are not inherent in the dark side of human nature (the perspective of Platoon) but are instead socially produced.

The boot camp is a microcosm of a society being trained and educated in national chauvinism, racism, and sexism. This takes the form of lessons assimilated passively from lectures or learned by rote and repeated in the forms of songs. The drill instructor calls out the lines that the young school-age student-soldiers repeat or sing while they march. They acknowledge his lectures by assent (“Yes, sir!”) while standing at attention. These devices allow Kubrick to foreground the ideological aspects of the training process while maintaining the dramatic flow of the narrative. The lectures and drill songs coalesce into a curriculum: For example: “I love working for Uncle Sam/Let’s me know just who lam.” “You will be a weapon/You will be a minister of death.” “I don’t want no teenage queen/I just want my M-14.” “Niggers, wops, gooks, or greasers. Here you are all equally worthless.” “What makes the grass grow?”/ “Blood, blood, blood.” “What do we do for a living?”/“Kill, kill, kill.” The violence of the process—the shouting, the punishments, the sadism—is also part of the curriculum. The young men are molded into gook-hating, misogynist, robotlike killers during their period of basic training. They graduate as U.S. marines. They know what they are fighting against but have little sense of what they are fighting for. As one marine says: “Do you think we waste gooks for ‘freedom’? If I’m gonna get my balls shot off for a word, my word is ‘poon-tang.’ ”

The main section of the film duplicates the structure of the conventional war film: we follow the lives of the recruits from boot camp in the United States to Vietnam. As in the prologue, however, Kubrick reproduces the outline of the war-film narrative to deconstruct the convention. In the remainder of the film he continues to develop his critique of racism and sexism in the armed forces—of attitudes that effectively stereotype and dehumanize Vietnamese women and men as alien, as “others.” In addition he challenges the national-chauvinist assumption that, given the superiority of the U.S. troops, most battles, if not the war, were won (or were winable). In these respects Full Metal Jacket is a significant corrective to films as diverse as Rambo II or Platoon.

The Vietnam section of the film starts in Da Nang and moves on to the ancient city of Hue during the 1968 NLF Tet offensive. In Da Nang we begin with a scene that is set away from the war zone. We quickly sense that the culture of Vietnam has also become a casualty of the war, a parody of the consumer capitalism of its foreign occupiers. In the foreground are several of the troops from the marine company, including Rafter Man and Joker; the latter is somewhat similar in education and background to Chris Taylor and witnesses the key events in the film. They are passing the time sitting at a table in a cafe talking with a Vietnamese prostitute, trying to get her to lower her price.1 Her identity has been reduced to a Western sexual commodity. She is dressed in U.S.-style streetwalker clothes—a short tight skirt, high boots— and does her best to negotiate in American: “You want fuckee? Me so horny. Me fuckee, fuckee.” In the background an enormous advertising billboard rises from the top of a building. It looks something like the Camel cigarette billboard in Times Square in New York City. On the left of the billboard there is a large cartooned face of a man, in this case semi-Asian and smiling, with a lot of teeth. The rest of the billboard is covered with advertising copy in Vietnamese. On the sound track of the film Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking” is blasting.

The scene, rendered for the most part in a long shot so all the signifiers are equally present, is a perfect icon of Coca-Cola imperialism. Both the prostitute and the Asian face are grotesque parodies of materialist American culture reminiscent of the Dr. T. J. Eckleburg billboard that overlooks the wasteland of the Valley of Ashes in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel about the American Dream, The Great Gatsby. Kubrick’s juxtaposition signifies that Third World and colonized people can only be conceptualized by the colonizer insofar as they attempt to assimilate his culture (in this case by becoming commodities). They are only valued insofar as they accommodate to imperialist prerogatives. As a marine commanding officer says: “We are here to help the Vietnamese because inside every gook there is an American.’’ The boots in the song signify America’s presence in Vietnam, walking all over the country and the culture. As the scene draws to a close the screen fades to black and in the darkness the concluding words of the chorus are repeated by the female voice of the singer: “These boots are gonna walk all over you.” It is an indication—almost subliminal—that some sort of reversal is going to take place.

The reversal occurs when the squad of marines, led by Sergeant Cowboy, panics and loses discipline when it comes under NLF sniper fire. This is the group that we observed being molded into a fanatic fighting force, confident of its inherent national superiority. (They were told in basic training that “God has a hard-on for the U.S. marines.”) The battle scene is overlooked and anchored by the image of the Americanized Asian face that was present on the billboard in Da Nang, as the shattered remnants of a duplicate billboard are on the side of a building that has been blasted in the battle. In this context his gaze signifies that the seemingly colonized culture is more resilient than the occupiers realize. Moreover, when the marines are pinned down by a sniper and four are killed, the discipline of the macho war machine breaks down in panic and recrimination and they abandon the object of their mission. Somewhere in the distance a Vietnamese person has intervened to destroy the confidence and cohesion of the elite fighting force of ubermenschen. When the lone sniper is revealed to us to be a Vietnamese woman, the ideological mold of the conventional combat film is shattered.

The sniper is a woman. As such, she represents the object of the twisted sexuality that has been articulated in the basic training marching songs and demonstrated in the soldiers’ brutal encounters with Vietnamese prostitutes. She is also nonwhite, and thus falls into the category of human beings the drill sergeant specifically designates as “worthless” in the first section of the film. She is also a Communist and, by implication, a non-Christian. She is as “other” as “other” can get to the representatives of American culture who encounter her presence. Her appearance shatters not only the conventions of the combat film—and the expectations of the audience—but also the ideology of the larger culture from which these conventions spring.

Equally important, she is the avenger of the imperialized and chauvinized prostitute who took center stage when the squad of marines first arrived in Vietnam. The bravest and most skillful representative of the other side is a woman. She is thin, even skinny, in contrast to the bare-armed, grotesque, muscle-bound grunts. She thus appropriates the male warrior role of the marines and in a sense of all the U.S. soldiers whose presence dominates the mideighties crop of buddy war films that are set in Vietnam and whose exploits often reduce the conflagration to a boy’s own military adventure. It is significant, however, that Kubrick’s critique of the war ethic extends beyond mere role reversal. The scene is shot in slow motion so we attend carefully to every detail of what happens. In the midst of the fight in which, very much outnumbered, the young woman is surrounded and shot by the marines who have managed to survive her attack, there is fear in her eyes and in the eyes of our figure of reference, Corporal Joker, who has by now come to doubt the war. They are bonded in common humanity, in contrast to the other marines, whose eyes blaze with sadistic energy as they blast their weapons. The look in her eyes and in the eyes of Corporal Joker is the only glimmer of potential redemption in Kubrick’s bleak and savage film.

In the next and concluding scene the marines march off through the burning city of Hue into the darkness. They are singing. However, it is not the confident and affirmative marines’ “Battle Hymn”—“from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli … the streets are guarded by the United States Marines”—that they practiced in boot camp in the early part of the film and that has been sung in triumph at the moment of closure in many Hollywood war films. Instead, the marines sing “Mickey Mouse is the leader of our club… /Mickey Mouse, Mickey Mouse/Forever let us hold our banners high,” as they march into the sunset on the road to nowhere. Full Metal Jacket, in contrast to the rhetoric of Rambo II and its appropriation by the commander-in-chief in the White House, asserts that after Vietnam the ideal of easy military conquest of a Third World nation cannot be simply affirmed in conventional discourse as relatively unproblematic. Its sound and image fuse into a complex trope: an army that sought world hegemony is linked with an ersatz culture, itself an aspect of that hegemony. There is an ironic ersatz glee in Kubrick’s construction of the scene; his reduction of sacred heroic marine ritual to kitsch brings to mind the horrific banalities of Nazi culture. The analysis is further historicized through the implied ironic association with film images of the U.S. cavalry going into the sunset, in this case the glow of the flames of the city the marines are protecting. The reference to Mickey Mouse as the leader of the club/army/society is not only surprising but suggestive. Mickey Mouse, of course, is a Hollywood artifact. At one level this may be a reference to the Hollywood antecedents of the incumbent commander-in- chief in 1987 when the film was made. More important, the cluster of associations—Mickey Mouse, U.S. film representations of the cavalry in Westerns, the marines in Vietnam—suggest that the hegemony of an ideology that incorporates national chauvinism, racism, and sexism in the media and culture as a whole, can be a key factor in constructing a consensus of popular support for war or domination of Third World nations or peoples. The film ends on a bleak note. As the final image fades we hear the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black” on the sound track. Kubrick is far from optimistic about the possibility of change.

Although the raw material for the film Full Metal Jacket comes from the novel The Short Timers (1979) by Gustav Hasford, the key sequences are essentially Kubrick’s. He has constructed Full Metal Jacket by conflating two chapters of the book: in the first chapter, in Hasford’s version, the Marines kill a woman NLF fighter, then butcher her corpse with a machete; in the next chapter they are pinned down by sniper fire and are on the verge of a suicidal attempt to save the lives of four wounded and dying marines when Corporal Joker shoots his buddies to put them out of their misery and abort a futile attack that would have resulted in additional loss of life. Instead Kubrick foregrounds the figure of the woman NLF fighter and concludes with the ironic scene of the marine Mouseketeers marching into the sunset. The rhetorical and often parodic use of background music on the sound track—“These Boots Are Made for Walking” and “The Mouseketeers’ Song,” as well as the Stones’ “Paint It Black”—are also Kubrick’s contribution. Equally important are the inclusion of songs in the background to the narrative that are examples of a debased culture whose artifacts are displays of hypocritical sentiment: “The Chapel of Love”; “Surfer Bird”; “Hello Vietnam,” the country/ western song heard at the beginning of the film. This illustrates how painstakingly Kubrick has constructed a critique of the chauvinist assumptions, sense of national superiority, and moral complacency of the conventional combat genre film set in Vietnam—and of the larger culture that the discourse of these films represents.

The achievement of Full Metal Jacket is incomplete, however, insofar as it is rendered through the structured absence of the potential for resistance to the war or of information about that resistance, which is part of the historical record. That is, the film is problematic in that it does not recognize that a counter-hegemonic ideology existed, that acts of resistance to the war were possible and when achieved were often heroic and significant. From perceptions of despair and anguish many who lived through the Vietnam years wrestled with the facts and transformed their hearts and minds in the process.

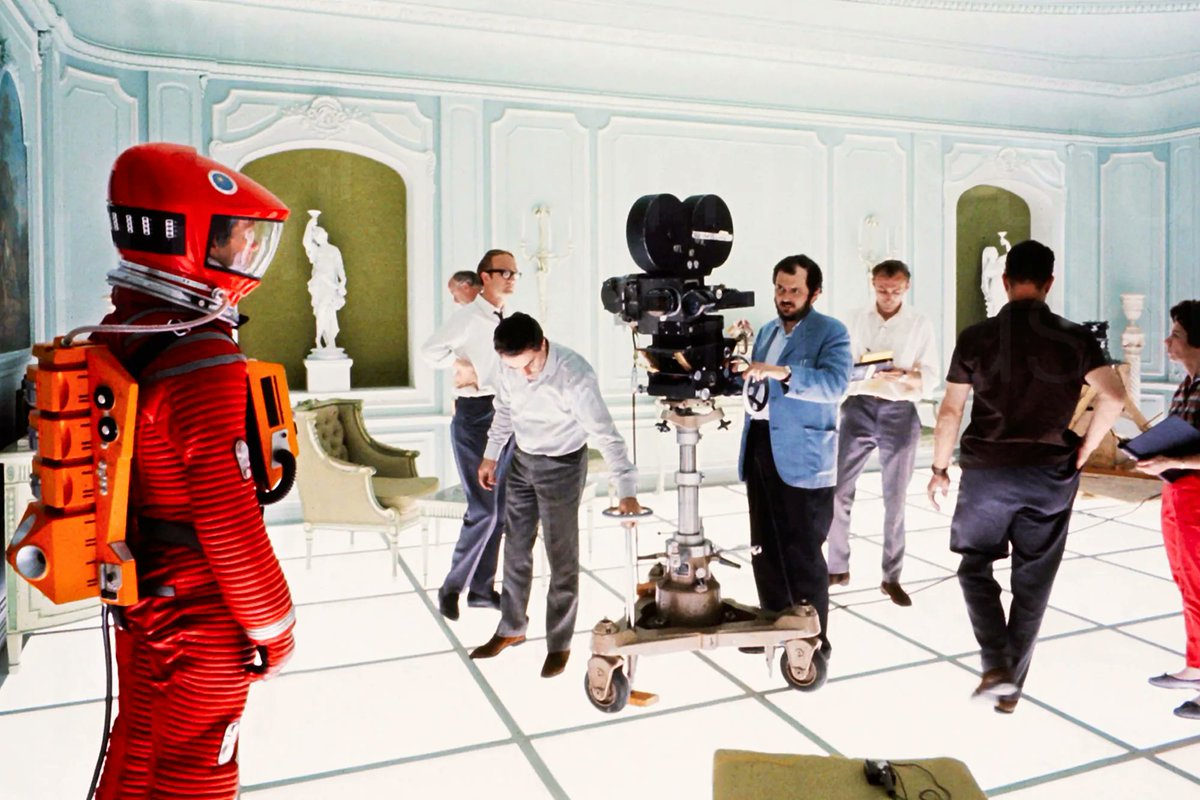

Thus, impressive as Full Metal Jacket is, it does have certain limitations. Some of these become apparent if we set it in comparison with Paths of Glory (1957), Kubrick’s first antiwar film, which is set during World War I. In that film a woman also appears at the conclusion to symbolize an alternative conception of humanity: a captured German woman whose song (which the French troops join in singing) for a brief moment unites nationalities who are trapped in an absurd and brutal interimperialist conflict. In Paths of Glory, the action of the narrative shifts back and forth from the grim field of battle to the plush and ornate marble-walled centers of military command. The generals in crisp dress uniforms who order the attacks are contrasted to the tired, dirt- encrusted soldiers. In this way the film explores related issues of class domination and privilege while it indicts a military caste system for its role in bringing about and perpetuating the war. This kind of analysis is rarely pursued in Full Metal Jacket.

In several important respects, Full Metal Jacket also shares the historical amnesia of other Reagan era Hollywood productions that are set in Vietnam.

Although the first half of the film occurs in the United States in 1967 and 1968, one has no sense that significant opposition to the war and the draft existed and was being expressed in teach-ins and demonstrations, as well as by soldiers in the coffeehouse antiwar movement on the fringes of armed forces bases in the U.S. Nor after seeing the film would one realize that in 1968, shortly after the Tet offensive, a squad of marines mutinied at Da Nang, or that marines and other members of the armed forces were active in opposition to the war, both in ‘Nam and at bases on the Pacific Rim (for example the U.S. 1st Marine Air Wing at Iwakumi Air Base),2 or that they published the Grunt Free Press and an estimated 144 other alternative newspapers to counter the propaganda of the Stars and Stripes, and as the war continued organized the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) in the U.S.3 From seeing the film one would not be aware that at Christmas 1968 30,000 troops at Long Binh demonstrated their opposition to the war by giving a peace salute to General Creighton Adams.4 Or that from 1966 to 1973 191,840 young men refused to respond to draft notices, that 503,926 U.S. soldiers deserted the armed service,5 and that by 1970 over 200 officially verified fraggings were taking place per year.6

There are brief moments when the ideological mind-set molded in the boot camp cracks, but the consciousness of the marines in Full Metal Jacket does not coalesce into a viable alternative perspective: we do not, for example, sense that it is possible that some may return home and join the VVAW and organize protest against the war, although that course of action was taken up as the conflict continued. Joker, our guide throughout the film, begins to distance himself from the war, at first through wry remarks (for example: “I wanted to meet interesting and stimulating people of an ancient culture and kill them”) and gestures (combining a peace symbol with his military gear) that simultaneously express the contradictions in his situation and attempt to hold it in stasis. Later, after the experience of affinity with the Vietnamese woman fighter, Joker appears to be developing a fragile humanist anti-imperialist discourse that might be a source of renewal and resistance.

This faint glimmer of possible change does not finally rescue the film from its Hobbesian pessimism, however. There is nothing to replace the deconstructed ideology of the boot camp, nothing to indicate that people could progress in consciousness beyond recognition of their complicity and entrapment in a policy of genocide. As the final image of the film, the march of the marine Mouseketeers, fades, Joker concludes, “I am in a world of shit,” and wills his mind to focus on a wet dream about a misogynist homecoming “fuck fantasy with Mary Jean Rottencrotch.” This too will be unfulfilling and is viewed with a sense of self-disgust. Then, as the credits begin, our ears are invaded by a cry of anguish. It is like a hitherto repressed interior narrative or submerged authorial voice. And as the anguished intervention through song begins just as Kubrick’s name comes up on the final credits of the film, it not only qualifies the stoicism and amplifies the horror in Joker’s sense of experience of his role in the Vietnam War but also expresses Kubrick’s sense of rage and overarching tragic vision of history as socially produced nightmare.

I have to turn my head until my darkness goes . . .

I look inside myself and see my heart is black . . .

Maybe I’ll fade away and not have to face the facts

It’s not easy when your whole world is black . . .

Paint it black! . . . Paint it black! . . . Paint it black!

The final moments of Full Metal Jacket have a wastelandlike intensity that echoes Lear’s cry of despair and Kurtz’s howl of recognition in the heart of darkness. Yet in one sense the conclusion of the film is incomplete. For a more comprehensive interpretation of the Vietnam era, that is, for perspectives that Kubrick’s film excludes, we have to turn to the record of independent film production in the period.

Pierre Macherey, in A Theory of Literary Production (1966), has called our attention to the phenomenon of structured absence in art and other forms of communication, to the significance of what is left out of an account of an event, to what has been forgotten, suppressed, repressed, or decontextualized as memory of the past is revised in accord with the prevailing ideological drift. These images can be recovered from the record of independent counter- hegemonic documentary films made in the Vietnam era. They remind us that there was a good deal of resistance to the war and to aspects of American culture and society that sustained the war, both outside and within the armed forces. They correct not only the jingoistic excesses of The Deer Hunter, Rambo II, and so on, but also the Hobbesian pessimism that is often expressed in Full Metal Jacket.

During the Vietnam era, radical films critical of the war or of the injustices of racism and poverty in American society, or sympathetic to Third World revolutions, were widely seen at teach-ins and antiwar cultural events, on campuses, in 16mm cinemas, on television. It was a period in which alienation often led to commitment. The war and the civil rights movement and liberation movements at home and abroad sparked a reevaluation of the premises of life in America that was far more critical than the perspectives of recent Hollywood films about the Vietnam era. The issues were contextualized and interrelated. A general analysis emerges from these films in which the U.S. is seen as having reached a critical point in its development: social happiness, economic democracy, community, equality, freedom, and justice at home and peace in the world could only be attained in the future through a new politics based upon a set of values and priorities very different from those that prevailed in the period of the Cold War and U.S. hegemony in the Third World. The independent film record is one index of the consciousness of the broad and representative movement that flowered in the 1960s and early 1970s. At least 164 16mm documentary films circulating in the U.S. in 1975 focused on the politics and events of the time from a counter-hegemonic perspective.7 They can be divided into the following subject topics:

1. Films that took as their subject what was called the war at home—the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, trade union and workers’ struggles, prison revolts, student struggles on a range of anticapitalist issues. For example: Angela: Portrait of a Revolutionary; Attica; The Columbia Revolt; Finally Got the News; Don’t Bank on America; The Black Panther Party.

2. Films that focused on the antiwar movement within the United States and within the Army in Vietnam. For example: Vietnam Day Berkeley: 1964; The Confrontation at Kent State; The Trial of the Chicago Seven; The Day We Seized the Streets of Oakland; F. T.A.; No Vietnamese Ever Called Me a Nigger.

3. Films that focused on cultural, economic, and political events in the Third World from a socialist or anti-imperialist perspective. For example: Felix Greene’s China; The Hour of the Furnaces; The Bay of Pigs, an indictment of the U.S.-sponsored invasion of Cuba.

4. Films that viewed the war in Vietnam from an anti-imperialist perspective. For example: In the Year of the Pig; Interview with Ho Chi Minh; Interviews with My Lai Vets; Introduction to the Enemy; For a Vietnamese Vietnam. In some cases documentary films highly critical of the U.S. war in Vietnam were shown on national television: Inside North Vietnam; The Selling of the Pentagon; Hearts and Minds.

5. In addition, at least twenty-three films in distribution in the U.S. in 1975 were made by filmmakers in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam or in the liberated zones in the South. They presented the National Liberation Front’s and Hanoi’s perspective on the war. For example: Hanoi Tuesday the 13th; Our Children Accuse; Toxic General Warfare in South Vietnam; Ten Girls of Nai Mountain; The Tet Offensive. These communicated the perspective of “the other side” to American audiences.

Thus, during the height of the war, when the Vietnam issue was most controversial, and at the height of the struggle against the war, a large body of films critical of U.S. intervention was in circulation. It focused upon resistance to the war at home and within the armed forces, and included consideration of the Vietnamese perspective.

Films like Platoon or Rambo II or The Deer Hunter cannot heal the American psyche, cannot reconcile lingering divisions in the American people about U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam or prepare us for the challenges of the 1990s. They do little to enhance our consciousness of history or to clarify our understanding of the political, economic, and ideological factors that sustained the war or that brought the war to an end. Film and television can, however, play a role in this process as they did in the antiwar period. This will require a new language, a new set of images, and a new politics. Recovering the images of the 1960s and deconstructing 1980s Hollywood representations of the Vietnam era is part of a dialectical process through which attempts to create a better America and a better world can progress with a sense of social memory.

NOTES

1. Vietnamese sources estimate that three-hundred-thousand women became prostitutes in the south of Vietnam under French and U.S. occupation. The Indochina Newsletter (U.S.: November/December 1982) estimate is two-hundred-thousand prostitutes. In either case it illustrates how disruptive and decadent the process of neocolonization was.

2. The scenes are recorded in Francine Parker’s documentary film FTA. We have no sense of this in the film Full Metal Jacket, or in the novel from which the film derived: Gustav Hasford, The Short Timers (New York: Bantam, 1985).

3. Steve Rees, “A Questioning Spirit: GI’s Against the War,” in Dick Cluster, ed., They Should Have Served That Cup of Coffee (Boston: South End Press, 1977), p. 150, estimates that 200 G.I. antiwar alternative newspapers were published during the war. Colonel Robert D. Heinl, in “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,” Armed Forces Journal, 7 June 1971, pp. 22-30 estimates 144. In either case it illustrates the scope of opposition and resistance to the war in the U.S. armed forces. This is what the films excise from historical memory. Pierre Macherey calls attention to the process of “structured absence” in A Theory of Literary Production (London: Routledge, 1978). To retrieve some of the alternative counter-hegemonic cultural work produced by the antiwar movement see: Jan Barry, ed., Winning Hearts and Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans (Brooklyn: First Casualty Press, 1971); Susan Sontag, “Trip to Hanoi,” in Sontag, Styles of Radical Will (New York: Delta, 1969), pp. 204-274; Norman Mailer, The Armies of the Night: History as a Novel/The Novel as History (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968).

4. Reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, 23 December 1968.

5. Reported in The New York Times, 20 August 1974. These are official U.S. government figures and may understate draft resistance and desertion. Again, the Hollywood post- Vietnam construction of the Vietnam era gives no sense that this took place.

6. Heinl, “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,” pp. 30-31: “By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse . . . dispirited where not near mutinous.”

7. Kathleen Weaver and Linda Artel, eds., Film Programmers Guide to 16mm Rentals: Third Edition (California: Reel Research, 1975).

Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud (edited by), From Hanoi to Hollywood. The Vietnam War in American Film, pp. 29-40