PHOTOGRAPHING STANLEY KUBRICKS’ The Shining

Lighting the sets for a huge hostelry with mainly practical lights created a special challenge, but also offered several advantages

The Shining, a Stanley Kubrick Film and Warner Bros, release, currently playing the screens of the world, is based on the best-selling novel by Stephen King. It was produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick from a script written by himself and Diane Johnson.

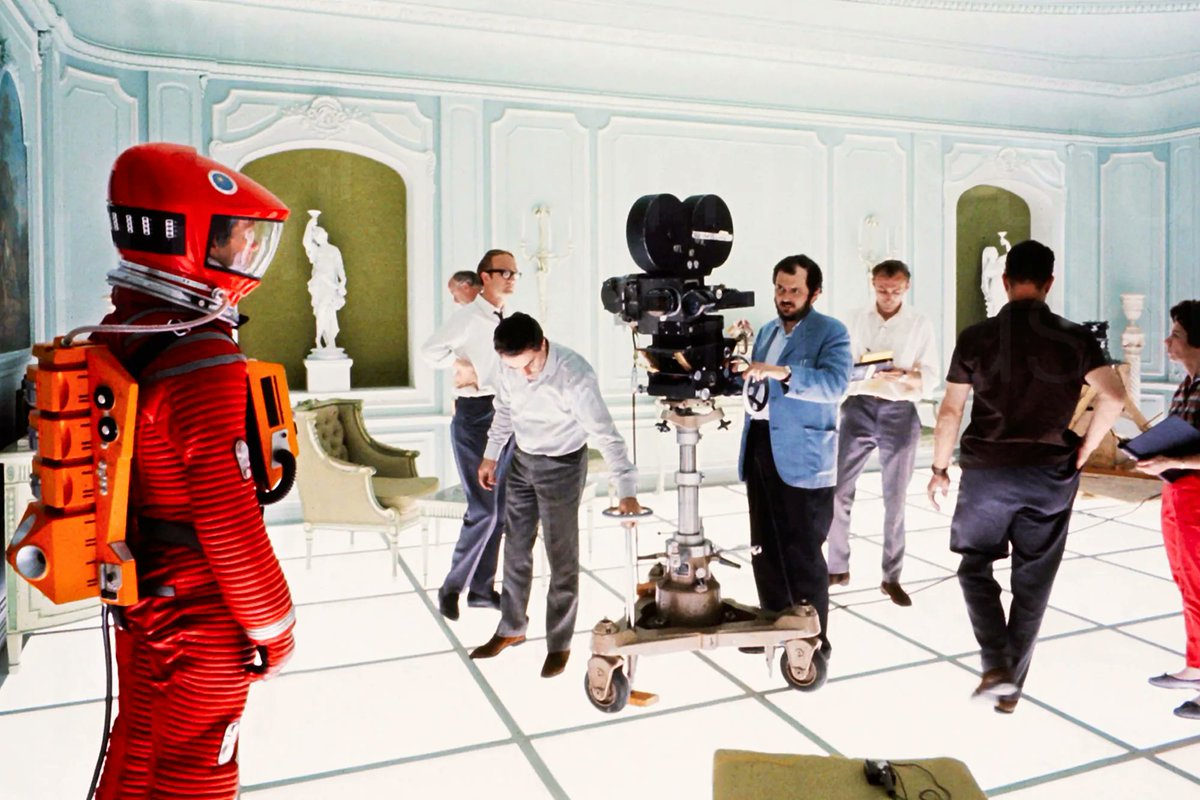

The Shining was photographed by John Alcott. BSC. who says that Kubrick “gave him his first break” on 2001: A Space Odyssey by asking him to carry on as cinematographer when the picture’s Director of Photography, the late Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC. had to leave the production after six months in order to fulfill another commitment. The two men have since worked together on A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, for which Alcott received the 1976 “Best Cinematography” Academy Award.

In the following interview, conducted by American Cinematographer Editor Herb Lightman recently in New York, where John Alcott was at work as Director of Photography on Fort Apache. Alcott discusses in detail the challenges and techniques involved in photographing The Shining.

QUESTION: Starting from the beginning, can you tell me how much pre-production planning time you had for your assignment as Director of Photography on The Shining?

ALCOTT: Stanley Kubrick gave me the book to read about ten months before we were to start shooting and, although I had several other shooting assignments in between, this gave me time to be constantly in touch with him and check on the situation regarding the set that was going to be built-whether it should contain ten windows or only five windows, whether the fireplace should be located in one part of the room or the staircase in another-which proved to be a great asset for me in developing a visual concept for the film. This kind of direct contact prevailed throughout pre-production and I would always make a point

of visiting him whenever I was back in England in order to see how the set construction was progressing.

QUESTION: Did you have a chance to study sketches or renderings of the sets before construction began?

ALCOTT: What we did at the very beginning was to have all of the sets built in the form of cardboard models. They were painted in the same colors and had the same scenic decor as we intended to use in the film and I could actually light them. With this concept of using artfoam cardboard models I could light the set with ten windows and then with five windows and photograph it with my Nikon still camera, using the same angle we would use with our motion picture camera. That would give us some basic idea of how it was going to look on the screen. We went all the way through the film like that, even for the sets which were built perhaps two months after we started shooting. All of the major sets-the hotel lobby, the lounge, Jack’s apartment, the ballroom and the maze-were built in model form first, so I was able to do some careful planning. By this time we were probably about four months from our starting date and I would make it a point to visit the sets at least once a week, even though I had other commitments. Meanwhile, my two gaffers, Lou Bogue and Larry Smith, were doing the enormous amount of wiring necessary for the sets.

QUESTION: Do I understand correctly that most of the lights used for the photography were actual practicals in the sets?

ALCOTT: Yes. the lights were wired as actual practicals. They were part of the hotel. The gaffers started their work about four months prior to shooting because there was an awful lot of internal wiring to be done, and I would check at least once a week to make sure everything was going fine. They had to wire a great many wall brackets and chandeliers. For example, in the main lounge and the ballroom there were 25-light chandeliers which contained FEP 1000-watt, 240-volt lamps (the same lamps that are used in the Lowel-Lights). Each five of the lamps were connected to a 5 Kilowatt dimmer, so that I could adjust every chandelier to any setting I wished, and this was all done from a central control board outside the stage. The service corridors, which were outside the hotel lobby and the main lounge, were all lit with fluorescent tubes.

QUESTION: Fluorescent lighting always presents its own special set of problems. How did you cope with those?

ALCOTT: Because the humming of the fluorescent tubes does indeed create a problem, all of the controls and ballasts and transformers were taken outside into the corridors of the studio, so there was no sound problem whatsoever. But this called for another great wiring job, because every tube had to have two wires going up and two wires coming back again. However, at least we eliminated the humming. We had no color temperature problem because the fluorescent tubes we were using were the Warm White Deluxe Thorne tubes, the ones which I’ve found in all my tests that come closest to matching incandescent lighting at 3200°K. In America I use the General Electric equivalent of these tubes.

QUESTION: You mentioned that the dimming of the practicals was controlled from a central board outside the stage. Can you tell me how this worked out during actual shooting?

ALCOTT: They were all on dimmers on the board and I could control the whole situation by remote control through the use of a walkie-talkie. This was especially convenient for the Steadicam shots-and there were an awful lot of them. I could change the light settings of the chandeliers as the Steadicam was traveling about the set simply by talking to the control room. This happened in several instances and it was a great help.

QUESTION: The main lounge of the Overlook Hotel, which was built inside a huge sound stage at EMI Studios in England, nevertheless had very large windows which seemed to face the outdoors and let in a great deal of diffused “exterior” light. Can you tell me how you achieved that lighting effect?

ALCOTT: Creating that exterior lighting was quite a project. We had the Rosco people make up an 80- by 30-foot backing of one of the Rosco materials which had the diffusing quality of tracing paper. They welded together the sections of material to give us this complete one-piece backing. The set for the lounge had a kind of small terrace outside with trees behind it. Then came the backing, and behind the backing there were mounted 860 1000-watt, 110-volt Medium Flood PAR 64 lamps. That was a lot of lamps and a lot of light-and a lot of heat I mean, you just couldn’t walk from one end to the other between the lights and the backing. You just couldn’t make it.

QUESTION: How were the lights mounted?

ALCOTT: They were mounted on 40-foot tubular scaffolding and they were all built upright and placed at two-foot intervals. Each lamp was on a pivoted ball-bearing mount and they were all linked together, so that I could vary the light from a control inside. For example, we could start the shot off with the Steadicam pointing in one direction. I could have the light pointing toward me and then, by the time the Steadicam had traveled through the service corridor and around the back of the set and come in again, I could have the lights coming back again. This was possible because all the poles were linked together with one rod. You just turned the handle and the whole bank turned together. I remember going to a meeting and saying to Stanley, “The ideal thing for me would be if the lamps were on ball-bearings.” And he said,”Put them on ball-bearings. If it’s going to work, do it.” It gave us a terrific advantage, because I could very easily alter the direction of not just the whole bank of lights, but different poles and different parts of the backing, which, again, could turn in one piece. It was a great asset.

QUESTION: Assuming that all of this was worked out well in advance of actual production, how did things change as you approached your shooting date?

ALCOTT: What happened was that when we eventually got the sets built-and some of them were as much as eight weeks in building-I started pre-production full time. This was three to four weeks before we started shooting, which enabled me to basically light all the sets before the cameras rolled. What I did was something that I had never done before: I lit all the sets and shot all my tests with the Nikon camera. I found that I could get around much easier and quicker and I could shoot 36 tests on one roll of film. Whereas, if I’d had a crew and motion picture camera wandering around on sets, it would have taken a lot more time. I did this purely as a lighting test and I could shoot varied tests with the different lighting effects, different settings, less chandeliers, more chandeliers, some on, some off, and so on. I did this continuously with all the sets and I used to view the results the next day. If I didn’t like something I could go back and decide on something else. By the time we actually started shooting the picture, virtually all of the sets were basically lit. so there was no kind of lighting that had to be done that hadn’t been done beforehand. As I say. I had never worked this way before, but I found it a great help and it left me with much more time than I d ever had before.

QUESTION: Didn’t having almost all of the sets built in advance also add up to a great advantage for you?

ALCOTT: Yes, I was very lucky in that respect. On most pictures all of the sets are not built in advance. They are built, struck and built again. But during the entire filming the sets were up continuously. Therefore, it was simply a matter of going from one set to another.

QUESTION: With so many sets up at one time, how did you keep track of your lighting logistics?

ALCOTT: When I was about to do all of my tests, I had the Art Department make me plans of every set on foolscap-type sheets that I could file with all of the lights in the different positions. I could mark them down at the settings I established. so that when I came back to each set I would just give the setting plan to the control room and get them to make their settings accordingly. Then I would go around and check my measurements. because sometimes they weren’t always true, but basically they were there and it just meant making a final adjustment here or there to get back to the same situation we had left about two weeks before. Working in that way. I found that I had to make a plan and I had one for probably every slate number I shot. I found it to be invaluable.

QUESTION: How did your lighting plan work with the Steadicam shots?

ALCOTT: Because most of the lighting was done within the set itself, using the practicals. if the chandeliers and light brackets were behind us, I would turn them up to a higher light level than the ones that I was photographing within the view of the camera, then, by the time the Steadicam had come around, I d have changed the setting, reversed the whole situation. This had to be down on the plan, as well, depending upon whether we were going to come back and intercut something or pick it up somewhere. For example, we had problems with shooting all of young Danny’s scenes, because he was only allowed to shoot 40 days out of the whole year. His time was from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon, and if his time ran out we would suddenly have to abandon his shooting and go on to something else. We would come back to it maybe not even the next day. It might be the next week, because it would have been silly to come back and pick up just that one scene and then lose a day of his shooting time.

QUESTION: I noticed when I visited the ballroom set at EMI Studios that the walls were covered mainly with a gold metallic material and the lighting seemed to be almost entirely indirect. Could you tell me about that lighting?

ALCOTT: There were three troughs on either side of the ballroom and in each trough there were 150 100-watt domestic light bulbs. I had those on dimmers, as well. and. again, they were operated from the control room. They were on a 240-volt system, but most of the time I had them dimmed down to 60 or 70 volts, which threw a kind of golden glow and that’s the kind of light I used for the sequence when Jack comes into the ballroom and it’s all back in the 1921 period. The bar was translucent glass and the back of the bar was lit by 100-watt bulbs which were banked in boxes of 25 to each panel. The band was lit in a special way. For each person playing an instrument I used one Lowel-Light. just to pinpoint them out. In that set I had to rig the chandeliers up high because they reflected back so much from the mirrored surfaces of the walls that, at certain points, they looked unattractive. There were other times when they became very attractive, so I had to make up my mind that in certain scenes they would be on and in other scenes they would be off.

QUESTION: Most of the sets you have discussed have been the huge public rooms of the hotel. What about the smaller sets—Jack’s apartment, for example?

ALCOTT: Jack’s apartment was lit, again, by fluorescent tubes, the same tubes I mentioned before. And inside all the practicals were wired, again, with the FEP 1000-watt. 240-volt lamps. So basically the rooms of this set. too, were lit by means of the actual practicals, supplemented sometimes with fill. I used to hang a little fill light behind the archway into the bedroom and the small lounge that they had. But basically the illumination came from a top hanging light and the table lamps by the bed and dressing table were actually the practical lights themselves. Again, outside the windows we had a translucent backing with the 1000-watt lamps behind it, but it was a much smaller backing than the other one-only about 20 by 30 feet.

QUESTION: What about the lighting of the maze?

ALCOTT: The maze was lit by the type of lights that are used for floodlighting in garden centers and that sort of thing. They were 1500-watt floods made by Thorne. That sequence was lit solely with those lights, with just a fill running behind. Garrett Brown did all the Steadicam work for us, including all that running around in the maze. I basically tried to place the lights so that everything was always in-picture that gave us a highlight, something which would expose the film properly. Of course, we had the snow all over the maze, which was very bright and gave us a lot of luminosity. I was usually stopped down to T/5.6, and even sometimes T/8 in that maze-and that was normal development. The whole picture was normally developed, which is the first time I’ve shot a picture with normal development throughout. We wanted depth of field, so it might have seemed logical to force the development. but we had so much light coming through the windows from the backing that I could work at a T/2.8 to T/4 aperture most of the time and that gave us sufficient depth. We weren’t quite sure at the time whether it would be a good idea to force the development because of the new stock, but we had made one or two tests and the forcing had added more contrast. So we went ahead with normal development and it worked out just fine.

QUESTION: Can you comment a bit on the use of the Steadicam?

ALCOTT: As I’ve said, Garrett Brown did all of the work with the Steadicam and it was used a great deal on this picture. It was used for most of the traveling shots you see when the Torrances are being shown around the hotel. For me, seeing the picture all cut together emphasized what a wonderful piece of equipment it is to use in that type of setting. Garrett is the ideal operator for it. Being such a tall man, he can go anywhere, and he seems to be so fit. It’s quite incredible. He really is a perfectionist at the art of the Steadicam and I have great admiration for his work. This particular film is a great showcase for the device because the story takes place in a very large hotel and one could only explain it being large and complex by traveling through it, and one could only travel through it the way we did by using the Steadicam. Otherwise, I don’t know how we would have done it.

QUESTION: I would say that the kitchen set alone presented a kind of obstacle course for the Steadicam. Isn’t that so?

ALCOTT: Yes. the kitchen set was a maze in itself with all that equipment. When one travels through the kitchen in the first sequence there are twistings and turnings in and out amongst the ovens and the kitchen furniture-a kind of backtracking. I don’t think you could find a dolly that could do that. The Steadicam was an ideal piece of equipment in that instance. We used it often in shots where you would have to start off from a very difficult position and continue on to where you perhaps could use a dolly, but Garrett would end up on a composition as precise as anyone could have done it with a dolly and a Worrall head. I must say it was terrific.

QUESTION: How were the shots done of the boy running around in his little racing car?

ALCOTT: That was the Steadicam, with Garrett operating it from a wheelchair. Stanley first had that wheelchair made up for use on A Clockwork Orange. It has the same basic construction as a wheelchair, but it was designed so that one could place different platforms on it, lie on it, stand up on it, sit on it and do all types of things while it was traveling around the hotel.

QUESTION: The exterior sets, Including the rear facade of the hotel and the adjacent maze, were built on the back-lot at EMI Studios. Can you tell me what kind of lighting was used for the night shots?

ALCOTT: The lights in the parking lot on the outside of the hotel were ordinary streetlight-type fittings with 2000-watt quartz bulbs in them. They were far too bright for the camera, but the heat was too intense for any gelatine to take them down, so I had some perforated metal which I could use on the camera side of the lights. If there were a moving camera shot that showed two sides of the light, I would use the perforated metal sheet on two sides of the light. It acted actually as a neutral density barrier, because although the light flared out, it flared out around the metal sheet. In other words, the many holes were flaring into one another and becoming just one bright light-but not as bright as it would have been without the shield. The streetlights that did not show on-camera were left free of the perforated metal shields in order to provide maximum set illumination. They were used for all the exterior lighting except for the lights on the outside of the hotel. I wanted to light the hotel so that it looked weird and mysterious, but, at the same time, wasn’t lit by an unknown source. So I imagined that the hotel would have floodlights on it, as most hotels do (especially at skiing resorts)-at the same time lighting it up, but not making it look too pretty. Then I also used smoke for the night exteriors, which again gave it a more mysterious look and softened the lights so that they weren’t so contrasty. The result was a kind of glow that was in keeping with the film itself, and especially the attitude of the hotel, as well. Although I used smoke, the intention was not to produce the effect of fog, but of cloud.

QUESTION: What kind of camera equipment did you use in photographing The Shining?

ALCOTT: Again, on this picture, we used the Arriflex 35BL. We had one of them that was used solely for shooting as our main camera, and the other one was geared up for Garrett Brown to use on the Steadicam. He used that 35BL the whole time throughout the picture. The only time he used the Arriflex 2C was for the running shots in the maze. It was very difficult running in all that snow, which was actually a layer of salt and polystyrene about a foot deep. The Arri 2C made it much easier for him.

QUESTION: What kinds of filters did you use in shooting The Shining?

ALCOTT: I didn’t use any filters on this film, because it was supposed to look different. It was supposed to have a hard look to it and it needed a lot of contrast. There was supposed to be no attractive softness about.it. The daylight was soft, of course, and the windows just naturally flared a bit, but without the use of the low contrast filters which I d used on previous productions. In the sequence where Shelley finds out that Jack has been typing not a story, but the same phrase over and over, it was supposed to be early morning and I wanted to create a kind of mistiness to suggest the early morning effect. That was the only time I used smoke within the set, except for a very slight amount in the ballroom sequence, when Jack goes in and finds the whole crowd there.

QUESTION: Did you order corrected or one-light dailies on this film?

ALCOTT: All the dailies were printed on one light, not so much because we didn’t want them graded, but because I d already decided during our testing period what type of printing lights I wanted. Therefore, I thought it best to stick to the one-light system, because then, if something was a bit off, I could tell whether it was anything to do with me. Most times, in a situation where I am working on location. I like the laboratory to correct for me, because I’m usually working with mixed light or light from a source that is out of control altogether. In such a case. I like to see how the laboratory handles it. But in a studio situation like this it was much better for me to have control over the laboratory and know that the printing lights that had been chosen were continued all the way through. Then, if something wasn’t right, I could alter it the next day-two points here or two points there.

QUESTION: What variations did you make in the color temperature of the light to enhance various moods of the film?

ALCOTT: In the beginning of the film I used just the ordinary straight daylight system. I’m referring now to the 860 bulbs shining through the backing outside the windows. When the Torrances first arrived and checked into the hotel, the whole thing was lit that way. without any color filter whatsoever. Then, when it started to snow. I changed the whole lighting system to a full blue. I put a full blue on all the windows, and by that I mean that the gels were actually sandwiched in between two pieces of glass. So I had a double pane put on all the windows and that’s why it wasn’t just a simple thing to make the change. It took the construction people at least a day to change all those windows in that large lounge (and also in the lobby) to a full blue, but it created a cold daylight effect for the snow sequences and gave me a much better contrast between the warm light of the chandeliers and the cold light coming through the windows.

QUESTION: The Shining is shot very straight. In other words, the visual treatment is devoid of all of the usual mysterioso effects that are conventionally used in horror films. That being the case, is there any instance in which you shot what might be termed a “special effect” in the camera?

ALCOTT: There is a sequence looking down from the balcony with Jack at the typewriter and the fireplace in the shot. I wanted to get a full fire effect, a nice big glowing fire in the fireplace, but I didn’t want to reduce the general lighting in any way because I needed the depth of field. So I shot the scene all the way through without the fire burning, then rewound the film, killed every light on the set. lit the fire, opened the lens up to T/1.4 and shot the fire by itself-which gave me a nice glowing fire. It was something I thought would be different to do and it was worth a try anyway. But I think that’s really the only kind of”special effect” we did in the camera.

QUESTION: Did you use any type of video assist on the cameras while photographing The Shining?

ALCOTT: Both Arri 35BLs were fitted with video cameras which enabled us to watch the scenes as played. This was especially valuable with the Steadicam. because everybody was virtually in the picture and the only way to view the scene was from outside in the corridor somewhere. Without the video set-up it would have been impossible to see what you had until you actually saw the rushes. I found also that the device which Garrett Brown has on the Steadicam for stop and focus control is great. I especially found the stop control to be extremely valuable in cases where it was an advantage to change the stop within the scene. I found that it was very good to be able to hold the control and be away from the camera, but watch the picture on the TV monitor. Most of the time it is very difficult to know what the camera is viewing when it is panning or tilting especially. You have some idea, of course, but with the TV monitor in front of you it s easy to judge to the finest degree of stop control. I just hope that perhaps in the future all camera manufacturers will bear this in mind and incorporate it into their designs.

QUESTION: Did you use any HMI lighting on this production?

ALCOTT: I think once, in Danny’s bedroom for a moonlight effect, but that was the only time. In fact. I haven’t used HMIs an awful lot until this picture that I am doing now (FORT APACHE), but I must say that I find them very good. I think one has to be careful as to which make of lamp one chooses and which company one rents them from, because they have to be in tip-top condition. They’ve got to be maintained to their fullest. They ‘re not like an ordinary light that you can hire out and switch on and as long as it comes on it’s alright, because it isn’t with an HMI. There are contacts and various other things that must be absolutely perfect, because if they are not. that’s v/hen flicker can occur without being the fault of the frequency. In other words, it s not always the frequency that gives the problem: it’s the connections and the bad maintenance of the lamps. But I always carry a frequency meter with me anyway, as a safeguarding factor. I think a frequency meter is one of the most valuable things one can have these days if you are going into HMIs. or even if you are going into fluorescent light for lighting. because in the northern part of England. for instance, you will often get a very weird type of voltage and you’ll never get rid of the flicker.

QUESTION: From what you’ve told me, most of your actual photographic light came from the practicals built into the set. Would you say that you used that kind of light more on this film than on your other films?

ALCOTT: When it came to sticking with the actual lights that were built into the set. the chandeliers and other practicals, the answer is that I did use such lighting in this film more than in anything I’ve done before, but I had to do this for a very special reason-and that was the Steadicam. Because of the Steadicam there was no way I could have used any floor lights. I couldn’t have any ceiling lights because the hotel lounges, if you noticed, are built in such a way that they are fixed: they are solid: they are there for keeps. The hotel was actually built wall-to-wall. As you went out of a hotel door you went into the studio corridor: it was that close. At any rate, in most instances, the lighting was what existed within the actual setting. I would use the chandeliers as my overhead lighting when they weren’t in the picture. In other words. I would use them as a supplementary light for the practicals which appeared within the scene. I’m speaking now of the wall brackets and the small chandeliers in the outer rooms of the main lounge.

QUESTION: But as “real” as practical lighting is, we both know that, from the aesthetic standpoint, it’s not always the best light with which to photograph a scene. That being the case, weren’t there times when, to insure the quality of the image, you had to use extra units to supplement the existing practical lighting?

ALCOTT: In instances where I could use additional light-for instance, under the table when Jack is on the floor groveling after he’s had his nightmare-I did use additional lights. But these would be basically Lowel umbrellas with Lowel-Lights inside them, and I would supplement that with a full blue in order to get the same daylight effect. The fact is that under the table there was no light, no matter what I put through the chandeliers. Sometimes I would have to boost the daylight in instances where I needed the extra depth, as well. So the answer is that yes, I did use supplemental light in quite a few instances, when it was called for. By “called for” I mean if it was not possible to use the light existing within the set itself. But whenever possible I did use the existing fixtures for supplemental lighting. For example, if Shelley was talking to Jack in the mid part of the lounge. I would use a wall bracket with tracing paper to soften the light falling onto her and I would bring it up to give the required amount of exposurable light. All of our lights were on dimmers using increments from 1 to 10. If my general level were 4. I might bring the supplemental light up to 6 and then put on a quarter-orange or half-orange to keep the color temperature consistent.

QUESTION: You mentioned before that in the ballroom set the chandeliers tended to pick up as reflections in the metallic gold walls. Did the metallic materials cause any other problems that you can recall?

ALCOTT: No. not really. In fact, it rather added to the whole effect. It reflected my light, which gave the set an overall golden quality. If I was fortunate enough, in the position the camera was in. to have the chandeliers on without any reflection. then I was fortunate enough to have the light of the chandelier bouncing off the mirrored surface, giving me an overall fill. The six troughs I mentioned-three on either side-gave me an overall top fill for basically the whole set. The practical small brackets around the ballroom I kept at a very low level because, being right next to the reflective material, they tended to burn out. I didn’t use them as a lighting source at all and they were much more effective as viewing practicals. On the dimmer scale of 1 to 10. the setting for those wall brackets was about 3. Each table had its own separate table light-an ordinary 25-watt bulb-but it was just enough, with the white tablecloth, to lend a luminosity to the features of the people seated around the table. That sequence had a period look to it- which, of course, it was meant to have.

QUESTION: You said that you used a bit of smoke in there. Was that all it took? You didn’t have to augment it with any fog filters?

ALCOTT: No, just the smoke-and it was very, very light indeed. In fact. I tended to put it just in the background. You get to the point with smoke that no matter what you do in the foreground, it just never shows. So that’s why I used it on virtually just the background half of the set. The light from the troughs gave it an overall glow which softened it. as well. Then, of course, there was the hard light at the bar coming from the cabinets behind the bartender. The bar was sort of a set of its own within a large set. but the hardness of that light made the rest of it look much softer, more of an illusion. Had there been no bar there at all it would have been flat and uninteresting. It needed that contrast in the foreground to give it the depth that it had.

QUESTION: I gather from what you’ve told me that whenever you needed a cold look It was a matter of filtering tungsten with blue gels. Were there ever any times during the shooting when you lighted for daylight balance with arcs, using white carbons?

ALCOTT: No. there was no time that arcs were used to create a daylight effect. The only time I used arcs was in the sequence where Shelley is running through the hotel just before she exits. She runs through the corridor into the lobby when she finds all the skeletons. I shot that with open arcs to get the very hard shadows which I found effective. And one other time, in the sequence where Scatman is phoning from his apartment in Florida. I used an open arc with a full blue filter to create a hard blue light, but that was intended more for a night effect. The only other light was the red practical burning in the background, which gave it a kind of separation.

QUESTION: The long establishing shots of what was supposed to be the Overlook Hotel actually were scenes of a real hostelry [The Timberline Lodge, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon]. Did you have the benefit of seeing those shots from the actual location before you had to light the hotel exteriors built on the EMI backlot?

ALCOTT: Yes, plenty of time, and it was very helpful. I should like to comment on the wonderful sequence which Greg MacGillivray shot from the helicopter in the first sequence of the picture. It was a great introduction to the film and some of the most beautiful helicopter work I’ve ever seen.

QUESTION: In working with Stanley Kubrick on The Shining-which marked the fourth feature that you’ve done with him—did you adopt any different method or approach to working together, or was it basically the same working pattern that you’ve sort of established over the years?

ALCOTT: I think that, as time goes on, Stanley becomes more thorough, more exacting in his demands. I think that one has to go away after having done a film with him, gather knowledge, come back and try to put that knowledge together with his knowledge into another film. He is, as I’ve said before, very demanding. He demands perfection, but he will give you all the help you need if he thinks that whatever you want to do will accomplish the desired result. He will give you full power to do it—but, at the same time, it must work. Stanley is a great inspiration. He does inspire you. He ‘s a director with a great visual eye.

QUESTION: Did you have much opportunity to discuss with him the visual style he wanted for this particular vehicle?

ALCOTT: He said he wanted it to have a different approach from that of previous films. He stated that he wanted to use the Steadicam extensively and very freely without having any lighting equipment in the scenes. In other words, he suggested that we let the practical lighting work for us without using any actual studio lights. It wasn’t easy. In fact, at first it was quite worrying, because while I had visions of how it could work, I wasn’t sure it would actually come into practice. Even though you might prelight certain pieces of sets and lighting models, you can’t tell what is actually going to happen when you get artists in position. This you can never visualize until you are given a set-up, which causes you to light it. By-then the sets have been built and it’s too late to change much.

QUESTION: How would you sum up the working rapport that has developed between you and Stanley Kubrick, having worked together on four features in succession?

ALCOTT: I feel that when you’re with Stanley the working relationship benefits from picture to picture. We’ve worked together since about 1965 and in working with him there is always a different outlook, a different idea: “Let’s try something different. Is there any way we can do it differently? Is there any way we can make it much better than it was before?” I feel that when you have as much time as I had on The Shining to make sure the sets are right and that the Art Director is building them to your lighting design, as well as his own design, it is a great privilege. You don’t have that privilege with someone who lacks the experience and the visual perception that Stanley has. He is willing to bend over backwards to give you something you may desire in the way of a new lighting technique and this is a great help. If you have somebody who is working that way it makes the job so much easier for you. I don’t think there is anything really different that has developed in our working relationship. He may be more demanding than he was before, but that makes it very easy for you when you go on to your next picture. To use an analogy in reference to our British game of Cricket: It’s like practicing with five wickets and playing three. You defend five and then when you come to defend three, it’s much easier.

* * *

THE STEADICAM AND “THE SHINING”

In constant use for almost a year, this Academy Award-winning camera stabilizer lends great fluid scope to Kubrick’s ultimate horror film.

by Garrett Brown

[Editor’s note: Garrett Brown and Cinema Product Corporation shared an Oscar in 1978 for the invention and development of Steadicam. Immediately after the ceremony, Brown left for London to begin work on Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.]

In 1974 Stanley Kubrick receives a print of the 35mm demonstration film shot with the original prototype of what would later be called the “Steadicam”. Kubrick’s telexed response is reprinted below:

VIA WUI +

CINEDEVCO LSA

HAWKFILMS ELST

TO ED DI GIULIO

2#•11•74

DEAR ED,

DEMO REEL ON HAND HELD

MYSTERY STABILIZER WAS

SPECTACULAR AND YOU CAN

COUNT ON ME AS A CUSTOMER. IT

SHOULD REVOLUTIONIZE THE

WAY FILMS ARE SHOT. IF YOU

ARE REALLY CONCERNED ABOUT

PROTECTING ITS DESIGN

BEFORE YOU FULLY PATENT IT,

I SUGGEST YOU DELETE THE TWO

OCCASIONS ON THE REEL WHERE

THE SHADOW ON THE GROUND

GIVES THE SKILLED

COUNTER-INTELLIGENCE

PHOTO INTERPRETER A FAIRLY

CLEAR REPRESENTATION OF A

MAN HOLDING A POLE WITH ONE

HAND, WITH SOMETHING OR

OTHER AT THE BOTTOM OF THE

POLE WHICH APPEARS TO BE

SLOWLY MOVING. BUT MY LIPS

ARE SEALED. I HAVE A

QUESTION: IS THERE A

MINIMUM HEIGHT AT WHICH IT

CAN BE USED?

BEST REGARDS, STANLEY

KUBRICK

HAWKFILMS ELST +

CINEDEVCO LSA

To date it cannot be said with complete conviction that the Steadicam has revolutionized the way films are shot. (Maybe it really should have slowly-moving parts underneath!) However, it certainly had a considerable effect on the way The Shining was shot. Many of Kubrick’s tremendously convoluted sets were designed with the Steadicam’s possibilities in mind and were not, therefore, necessarily provided with either flyaway walls or dolly-smooth floors. One set in particular, the giant Hedge Maze, could not have been photographed as Kubrick intended by any other means.

I worked on The Shining in England at the EMI Studios in Borehamwood for the better part of a year. I had daily opportunities to test the Steadicam and my operating against the most meticulous possible requirements as to framing accuracy, the ability to hit marks and precision repeatability. I began the picture with years of Steadicam use behind me and with the assumption that I could do with it whatever anyone could reasonably demand. I realized by the afternoon of the first day’s work that here was a whole new ball game, and that the word “reasonable” was not in Kubrick’s lexicon.

Opening day at the Steadicam Olympics consisted of thirty-or-so takes of an elaborate traveling shot in the lobby set, interspersed with ballockings for the air conditioning man (because it was 110 degrees in the artificial daylight produced by 700,000 watts of light outside the windows) and complaints about the quality of the remote TV image.

Although I had provided a crude video transmitter so that Kubrick could get an idea of the framing, I quickly realized that when Stanley said the crosshairs were to be on someone’s left nostril, that no other nostril would do. And I further realized that the crudeness of the transmitted image simply prolonged the arguments as to the location of the dread cross-hairs. Had I known on that first day that we would still be debating questions of framing a year later, long after the air-conditioning worked, I might have wished to become an air-conditioning man or a caterer…

THE SETS

I first met Stanley Kubrick during FILM 77 in London when Ed DiGiulio, president of Cinema Products Corporation, and I took the latest model out to Borehamwood to demonstrate it. At this time, The Shining was in its early pre-production stages. Stanley had engaged Roy Walker to design the sets, and we provided them with some food for thought by going over the various maneuvers that were then possible and, at Kubrick’s request, demonstrating the accuracy with which one could hit marks in order to pull focus in the neighborhood of T/1.4.

Throughout the following summer there were sporadic early morning phone calls from Kubrick and preliminary arrangements were made for my services, ostensibly to commence in December of 1978. In fact, the start date had been put back well into the spring when I was notified that I had won the Bert Easey Technical Award of the BSC. I decided to fly from Los Angeles to London to accept the award in person and to show Stanley some of our latest wrinkles. Cinema Products had just constructed the prototype of the new “Universal II-raised monitor” Steadicam and we had also devised the means to suspend the 35BL from the Steadicam platform, thereby permitting a whole new range of lens heights from about 18 inches to waist high. Kubrick seemed particularly pleased with the possibilities for low-lens shooting.

This time I was taken for a quick tour of the sets, including the monumental exterior set of the Overlook Hotel and the vast and intricate “Colorado Lounge” set with its interconnected corridors, stairs, and rooms on two levels. My excitement mounted as we progressed around corner after corner, each unexpected turn offering further possibilities for the Steadicam. Originally we had decided that I would rent some of the more exotic equipment to Kubrick and just come to England briefly to train an operator. However, as we continued, I became convinced that here was a unique opportunity for me. Kubrick wasn’t just talking of stunt shots and staircases. He would use the Steadicam as it was intended to be used – as a tool which can help get the lens where it’s wanted in space and time without the classic limitations of the dolly and crane.

The kitchen set was enormous, with aisles winding between stoves and storage racks. The apartment sets were beautifully narrow. Suite 237 was elegant and ominous. The Overlook Hotel itself became a maze; absurdly oversized quarters for the players, yet ultimately claustrophobic. Here were fabulous sets for the moving camera; we could travel unobtrusively from space to space or lurk in the shadows with a menacing presence.

I guess I wanted to be there myself because Kubrick is, let’s face it, The Man. He is the one director working who commands absolute authority over his project from conception to release print. The ultimate technologist, but more, his technology serves a larger vision which is uniquely his own. He is a film-maker in the most pure sense of the word. I learned a great deal about the making of movies from simply being on hand for the stupefying number of discussions which sought to improve one aspect or another of the production.

PROGRESS

During the year of production which followed, the science of air-conditioning was reinvented and you can be certain that just about every other branch of human learning was at least reexamined insofar as it touched upon the doings in Borehamwood. Laboratory science, lighting, lenses, and the logistics of lunch – all were scrutinized daily. For example, the offending video transmitter was soon replaced by adapting Ron Collins’ AC-operated unit into a much smaller DC version (which has been a mainstay of my Steadicam services ever since). I was determined to remain unencumbered by wires, so the propagation of the signal became the next drama.

Although Stanley knows an astonishing amount about an astonishing number of things, his grasp of antenna theory is weak. He is, however, a formidable opponent in an argument – with or without the facts – so some bizarre theorems were actually tested and a disturbing number of them actually worked. By switching to various antennas hidden behind the walls, we were finally able to provide Stanley with acceptable remote wireless video nearly anywhere within his sets. To annoy him we would indicate the forest of TV antennas aimed at the studio from suburban Borehamwood and imply that the TV signal was escaping the sound stage and being watched by a gaggle of “Monty Python” women every morning: “Ooooh, poor Mr Brown!… That take seemed perfectly good to me!” Somewhat later, our imitation ladies got even more sophisticated: “Ooh, must be the 24mm Distagon!, see how it’s vignetting in the viewfinder!”

The infant science of the Steadicam advanced during the year. With the expert assistance of Mick Mason and Harold Payne of Elstree Camera Hire, we constructed a number of new mounts to adapt the Steadicam to various wheeled conveyances. After one ride on the converted skateboard and one push on the custom sackbarrel, both went into the “Bin of Whims” never to be seen again. However, Ron Ford’s elaborate motion picture wheelchair proved more enduring. We made the first prototype of the “Garfield Bracket” to adapt the Steadicam arm to a Mitchell mount on the wheelchair. This was also useful on the Elemack and we later made use of the Elemack leveling-head on the wheelchair.

On the theory that one should ride whenever possible in order to concentrate on operating and forget navigating, I promoted every opportunity to use the chair. In a number of instances it was the only way to get the lens right down to floor level.

I think that useful progress was made in the area of operating technique. I had a chance to refine my own abilities in the most direct possible way. By repetition! (With playback!) Stanley made a number of useful observations and speculations about the interaction of the human body with machine such as this. Just how good can it possibly be? How close to the exact repeatability of a dolly shot? More than most filmmakers he knows the limitations of the dolly, and when it was necessary to have phenomenally good track, he rebuilt an entire 300-foot plywood roadway three times to get it smoother. During one difficult shot, Kubrick said gloomily that the Steadicam would probably get the credit for all the dolly moves in the picture anyway!

Although he would admit that I could produce a printable take by any reasonable standard within the first few tries, Stanley would seldom respond with anything but derision until about take 14. He did not appear to be comfortable until we were well beyond take 20. Since the editing was to occur entirely after the filming of the production, he wanted at least two and preferably three perfect takes on each scene. Basically this was fine with me. Although most retakes were for other reasons, I could see a gradual improvement in my operating with each playback. I learned the route like a dancer learns a difficult piece of choreography and I could relegate more and more of the navigating to my subconscious and attend to the rhythm of the shot. To be fair, Kubrick later admitted that in selecting takes he went for performance every time and that many were technically indistinguishable. (He has been known to mutter, upon sitting through twenty identical passes in the lunchtime screenings, “Damn crosshairs, they get me every time!”)

THE “TWO-HANDED” TECHNIQUE

Throughout the production I worked on what we now call the “two-handed technique”. I found that if one hand strongly holds the Steadicam arm and is used to control its position and its height, the other hand is able to pan and tilt the handle with almost no unintentional motion in the shot. Whereas before the act of booming up or down would always seem to degrade slightly the steadiness of the image, now one can maintain the camera at any boom height and yet not influence the pan or tilt axis at all. This understanding has been the key to holding the beginning or end position of a shot so still that one must examine the frame line carefully in order to find any “float” at all. Kubrick was often able to use the head or tail of a Steadicam shot as his master for at least a portion of a dialogue scene. Even if I got caught in an awkward position because of an unexpectedly quick stop in the action Kubrick would count the beads of sweat, cast a practiced eye on the twitching of a calf muscle and wait until he judged that discs were about to fly like frisbees before he would quietly call “cut”.

THE 35BL

In the beginning I was somewhat apprehensive about shooting an entire picture with the 35BL on the Steadicam, not to mention that it was for Kubrick. It did not prove to be as difficult as expected. My style of operating is fairly relaxed anyway, and with the chance to put the camera down and watch a replay on each take, one could continue indefinitely or until the next tea and bacon-roll arrived. Unfortunately there was a new MacDonalds nearby, so the evening break went through that phase, much to the disgust of the English crew. (The BL does become somewhat more burdensome with a full cargo of Big Mac’s on board.)

One advantage of the 35BL is its mass. It’s about 10 pounds heavier than the Arri IIc, but it allows a noticeably quieter frame. Also the BL is less affected by gusts of wind. All in all, I came to prefer it to the Arri IIc for general shooting.

CLOSE QUARTERS

From the beginning, Kubrick intended to shoot within some of the more constricted sets without flying out walls as often as usual. Since he wished to use wide lenses, in particular the Cooke 18mm, he used the capability of the Steadicam to rapidly boom up and down to avoid distorting the sets. As someone approached and passed the camera we held the proper head-room by changing the height of the lens rather than tilting and risking the keystoning of the verticals on the set. Throughout the shooting I kept an additional spirit level mounted fore-and-aft on the Steadicam so that I could keep an eye on the tilt axis.

The Steadicam can reverse its direction rapidly and without any visible bump in the shot so one can back into a doorway or alcove and push out again as the actors pass by camera. In addition, since there are no geared-head handles in the way and no need for an operator’s eye on the viewfinder, one can pass the camera within an inch of walls or door frames. The combination makes a formidable tool for shooting in tight location spaces. Of course, John Alcott was left with the lighting problems that result from this kind of freedom. However, I never heard him complain and he always managed to solve these difficulties in his usual imperturbable way. John personally flew in flags and dealt with some of the camera shadow problems that arise when you are seeing 360 degrees around a room.

In the Torrance apartment in Boulder, I had a shot bringing Wendy and the doctor back along the corridor from the bedroom, backing around in a curve, booming up, then way down as they sat on the sofa, finally holding still for 1/2 page of dialogue. There is nothing about this shot that would attract the undue attention of the audience, however the lens is just where Stanley wanted it throughout. This is exactly the kind of shooting that I am most interested in. I have an increasing reluctance to suggest to a director that I might be able to smoothly jump out of the window and land shooting. It may be a sign of getting older or perhaps it just represents the maturing of my taste for the moving camera!

In the Kitchen set, one of the best shots for the Steadicam in the picture involved backing up ahead of Scatman Crothers (Halloran, the chef), Shelley Duvall (Wendy) and Danny Lloyd (Danny) as the three take a winding path through rows of immense restaurant machines and huge stoves and racks of dishware. Even if there had been room to wheel a dolly along this path, the camera would have been required to stay more or less centered, which would have meant some very sudden pans as the camera’s axis swung around corners. In my case I took the least disturbing “line”, like a race driver going through turns, and so the result has an unearthly tranquility about it which seems to best fit the requirements of that particular scene. In short, with the Steadicam, one can choose to pivot on any axis: far ahead of the lens, the nodal point of the lens, the filmplane, or some point far aft of the camera. In the case of this shot, I was able to pivot my camera around an imaginary point halfway between me and the actors, and prevent violent swings from side-to-side as we made the turns.

In Jack and Wendy’s winter quarters in the Overlook, there were many spectacular opportunities for the Steadicam as the various players passed through the entrance hallway. For example, as we followed Wendy leaving the apartment, she would descend the three stairs just before the door and the camera would boom smoothly down in sync with her move. Then, as she passed through the door, I would boom up to negate the fact that I was now descending the same stairs, and then squeeze the matte box through the door just as it was closing. On several occasions I preceded Jack (Jack Nicholson) or Danny through the door and made the above maneuver in reverse. Obviously it is important that the camera doesn’t make an unmotivated dip or rise just before or after the actor gets to the stairs. It feels better if the camera can be disembodied and not required to climb stairs itself! Other shots that stick in my mind: the-over-the-shoulder on Jack as he climbs the stairs above the lobby to find Halloran, the very believable moving P.O.V.’s as Jack or Danny enter room 237.

SPECIAL MOUNTS

One of the most talked-about shots in the picture is the eerie tracking sequence which follows Danny as he pedals at high speed through corridor after corridor on his plastic “Big Wheel”. The sound track explodes with noise when the wheel is on wooden flooring and is abruptly silent as it crosses over carpet. We needed to have the lens just a few inches from the floor and to travel rapidly just behind or ahead of the bike.

I tried it on foot and found that I was too winded after an entire three-minute take to even describe what sort of last rites I would prefer. Also, at those speeds I couldn’t get the lens much lower than about 18 inches from the floor. We decided to mount the Steadicam arm on the Ron Ford wheelchair prototype that Stanley helped design years before and still had on hand.

This is a very useful gadget. It can be properly steered in either direction with a simple set-up change, and the seat can be mounted low or high depending on the requirements of the shot. We arranged it so that rigging pipes could be fastened anywhere on the frame, and Dennis (Winkle) Lewis, our very able grip, constructed an adapter for the Elemack head. The Steadicam arm was fastened to the Mitchell mount, and I could sit on the chair and easily trim the leveling head to remove any imbalance in the “float” of the Steadicam.

With Stanley’s BL in the underslung mode we were now prepared to fly the camera smoothly over carpet or floor at high speed and with a lens height of anything down to one inch. The results, as can be seen, were spectacular. In addition, the whole rig wasn’t so massive that it would be dangerous if the little boy made a wrong turn and we had to stop suddenly. Of course, we immediately constructed a platform so that the sound man and our ace focus-puller, Doug Milsome, could ride on the back.

Now the entire contraption got to be quite difficult on the high speed corners. Dennis had to enlist relays of runners to get us around the course. Finally we had an explosive tire blow-out and the chair “plummered in”, barely avoiding a serious crash. Afterward we switched to solid tires and carried no more than two people.

Stanley contemplated this arrangement and decided that the chair should have a super-accurate speedometer, and while we’re at it so should the Moviola dolly and the Elemack. Then we could precisely repeat the speed of any traveling shot, etc. (More control over a capricious universe!) I was afraid that I would be lumbered with some kind of outboard wheel to precisely regulate my own speed, so I was happy that nothing came of this particular idea. (Although I would have enjoyed knowing how many miles I didn’t run because I had the wheelchair rig!)

We used this set-up frequently in the weeks to come. In the fall I took a leave of absence for a month due to a prior commitment to shoot on Rocky II. An English operator named Ray Andrew very capably took over for me on this occasion and several others when I was required to commute back and forth from England to the U.S. Ray made a shot from the wheelchair in which the lens is one inch above the floor, moving slowly beside Jack’s head as he is being dragged toward the larder by Wendy. We also used the wheelchair with the lens at normal height to shoot a number of ordinary tracking shots through the corridors. The wheelchair was particularly useful when the camera had to move very slowly. If we needed to crab we mounted the arm on the Elemack dolly or the Moviola.

The operating technique in the chair also involves two hands: one for the arm, and one for the handle. You can easily jib over to the left and right, as well as boom up and down to compensate for slight variations in the course. We used this ability again to straighten out the camera’s path and cut corners in order to make these shots easier to watch. The only tricky aspect of shooting from the chair is that starts and stops tend to be dramatic. It is a little like carrying a full punch bowl in a decelerating rickshaw!

WIRELESS FOCUS AND IRIS PULLING

I brought to England the first prototype of Cinema Products’ sensational 3-channel wireless servo-lens-control, and Doug Milsome appeared to enjoy using it. He has a marvelous eye and something like a physicist’s knowledge of optics. I don’t think that we shot a soft frame in all the time I was on The Shining. He made up focus and iris strips on the servo-control for all the lenses. A surprising percentage of my shots on the picture involved iris pulls. We would commonly dial anything from 1/3 to 1½ stop changes and the results were undetectable on screen. Since we were often rushing through narrow spaces Milsome had to train his eye to pull focus from positions other than just abeam of the lens. We would get tangled in fantastic shifting choreographies and a wrong turn would find Doug outside the studio front gate, still gamely dialing the servo!

Kubrick has a fanatical concern for the sharpness of his negative. He resurrected the “harp test” for his lenses and then went beyond that to invent a bizarre variation on the harp test which positions one focus chart every inch for fifteen feet out from the lens.

The cameras were steady-tested nearly every week, and the dailies projectors (which belonged to Kubrick) were frequently torn down and rebuilt to cure unsteadiness due to wear. In addition, we shot with matte-perf film and our prints were made on the one and only captive printer at Rank that seemed to produce steady prints!

All this produced so much data that the results were subject at times to some confusion. The depth on one of the two BL’s was packed by a few tenths on the theory that the film “liked” the image to bite somewhat into the emulsion. Lenses which were front-focused “preferred” one camera; back-focused lenses “preferred” the other, A master chart explained the feelings of each individual lens. It would be an exaggeration to say that I understood this system completely, but I must point out that I never saw sharper dailies, so the lenses obviously prefer the long-suffering Milsome as focus-puller.

THE MAZE

The giant Hedge Maze set must be one of the most intriguing creations in the history of motion pictures. It must also be one of the most pernicious sets ever to work on. And folks, every frame was shot with the Steadicam. In its benign “summer” form, the Maze was constructed on the old MGM lot outdoors at Borehamwood.

It was beautiful. The “hedges” consisted of pine boughs stapled to plywood forms. It was lined with gravel paths, and contained a center section (although built to one side of the set) which was wider than the rest. It was exceedingly difficult to find one’s way in or out without reference to the map which accompanied each call sheet. Most of the crew got lost at various times and it wasn’t much use to call out “Stanley” as his laughter seemed to come from everywhere! It was amusing to be lost carrying nothing more than a walkie-talkie. It was positively hilarious if you happened to be wearing the Steadicam.

We determined by testing that the 9.8mm Kinoptik looked best, and that the ideal lens height was about 24 inches. This combination permitted a tremendous sense of speed and gave the correct appearance of height to the walls. The distortion was negligible when the camera was held level fore-and-aft. Much of the shooting consisted of fluid moves ahead of or behind Wendy and Danny as they learn their way through the Maze. Some of the best moments came as we followed them right into a dead end and back out again in one whirling move. I also made some tripod-type shots in the center of the maze since it would have been time-consuming to lug in the equipment to make a conventional shot.

Stanley mostly remained seated at the video screen, and we sent a wireless image from my camera out to an antenna on a ladder and thence to the recorder. For the first time I found the ritual of playback a burden, since I had to walk all the way out of the maze and back. We had made an early attempt to leave certain passages open to the outside. However, we found that we were constantly getting disoriented and a terrific shot would inadvertently wind up staring out one of the holes.

I discovered at this time that young Danny Lloyd weighed exactly as much as the camera, so we made a chair out of webbing and he would yell with delight as he swooped along riding suspended from the Steadicam arm. (I was sorry that I hadn’t thought of that one before my own son weighed as much as a BNC!)

The maze was then struck and re-erected on stage 1 at the EMI Studios. Roy Walker’s men proceeded to “snow” it in with two feet of dendritic dairy salt and Styrofoam snow crusted on the pine boughs. The quartz outdoor-type lights were turned on and a dense oil-smoke atmosphere was pumped in for eight hours a day. Now the maze became an unpleasant place in which to work. It was hot, corrosive and a difficult spot in which to breathe. The speed of the shots stepped up, since everything now happened at nearly a run. To lighten the load we switched to the Arri IIc from Joe Dunton Cameras and constructed a special underslung cage for it.

The “snow’ was difficult to run on. I constantly had a fill light clattering around my legs, and I had to navigate by the sound of muffled curses ahead as the lighting and focus-pulling intrepids fell over one another in the salt. I think that the most difficult shots on the entire picture for me were the 50mm close-ups traveling ahead of Jack or Danny at high speed. Milsome deserves a lot of credit for keeping on his feet and keeping them sharp.

For a special shot of the boy’s running feet which required a lens height of three inches we made up a copy of my earliest “Steadicam”: no arm, just camera, battery and magazine, connected in a balanced arrangement so I could run along “hand-held” with the lens right on the deck.

In the beginning we wore gas masks of various vintages. However, I found that I couldn’t get enough air to support the exertion of getting from one end of the Maze to the other. We never measured the linear distance from the entrance to the center, but I am sure it was a hell of a long way. This was the only time on the picture that I sometimes had to call a halt to the shooting until I could get enough breath to move again.

Stanley, meanwhile, watched the deteriorating video pictures from outside the set, like a wrathful Neilson family suddenly given absolute power over the programming. The faster we had to move, the worse it got. I sometimes thought wistfully of breaking an ankle in the salt. It required enormous force to pull the camera around the turns and a degree of luck to find the right path while essentially looking backward. In addition, we were all acutely aware of the danger of fire and how difficult it would be to get out of the maze if the lights went out, with real smoke and burning Styrofoam – a genuine nightmare!

The footage, however, looked sensational and the sequence is tremendous in the picture, so it is all, as they say, worthwhile. Some of the best stuff was slow-moving. As Danny backs up stepping in his own footprints to fool Jack, I had to back up ahead of him also in his footprints! To accomplish this I had to wear special stilts with Danny-shoes nailed to the bottom so I wouldn’t make the footprints any bigger!

As it turned out, there were very few stair-climbing shots in the picture. Ray Andrew shot one which worked extremely well as Wendy backs up the stairs swinging a baseball bat at Jack.

I made a “stairs” shot which is my all-time favorite. We are moving ahead of Wendy up three flights of stairs, starting rapidly, and smoothly slowing down until we are just barely moving ahead of her as she comes upon Harry Derwent and his strange doggy companion doing the unspeakable! A fabulous shot, despite the fact that we did it 36 times – multiplied by three flights equals climbing the Empire State Building with camera…

When I finally saw it on the silver screen I was glad to have made the climb, if for no other reason than…

“Because it was there!”

American Cinematographer, vol. 61 issue 8, August 1980