The American city of Seattle and the Canadian city of Vancouver have similar populations, economies, and crime rates, except for the rates of murder and assault by handguns. In the following viewpoint, Claire Safran reports that in Seattle, where handguns are readily available, residents are much more likely to be injured or murdered with a gun than in Vancouver, where guns are tightly restricted and difficult to obtain. Seattle’s higher rate of crimes and accidents involving firearms is due to laxer restrictions on gun ownership, she contends. Safran is a freelance writer.

* * *

“Every two years, more Americans are killed by guns at home than were killed in all the years of the Vietnam war”

Private Ownership of Handguns Leads to Higher Rates of Gun Violence

by Claire Safran

“Did I kiss her good-bye that morning? I can’t remember.”

Over and over, Jenny Wieland relives the events of November 20, 1992. She was rushing off to work in Seattle, Wash.; her one and only child, Amy, just 17, was getting ready for school. “Did I tell her that I loved her? Oh, I hope so.” It was the last chance she would ever have.

That afternoon, Amy stopped by a friend’s apartment. After a while, a 19-year-old boy arrived, high on cheap wine and waving a .38-caliber revolver. “Just fooling around,” he said, holding it to Amy’s blonde head. Alarmed, she told him to stop, then tried to push the gun away. And then the gun exploded.

Amy never regained consciousness. She died in the hospital the next day. The boy who killed her so carelessly? He was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison.

Amy Ragan (her parents were divorced, and she kept her father’s name) was a spirited, popular young girl who won blue ribbons at horse shows. Her mother buried her in her favorite clothes—jeans, Western shirt, silver belt buckle, and cowboy hat. Her grandmother placed a red rose in her hands. “I was supposed to see my daughter graduate from high school,” says Jenny. “I was supposed to see her get married and have babies. But a boy with a handgun ended it all.”

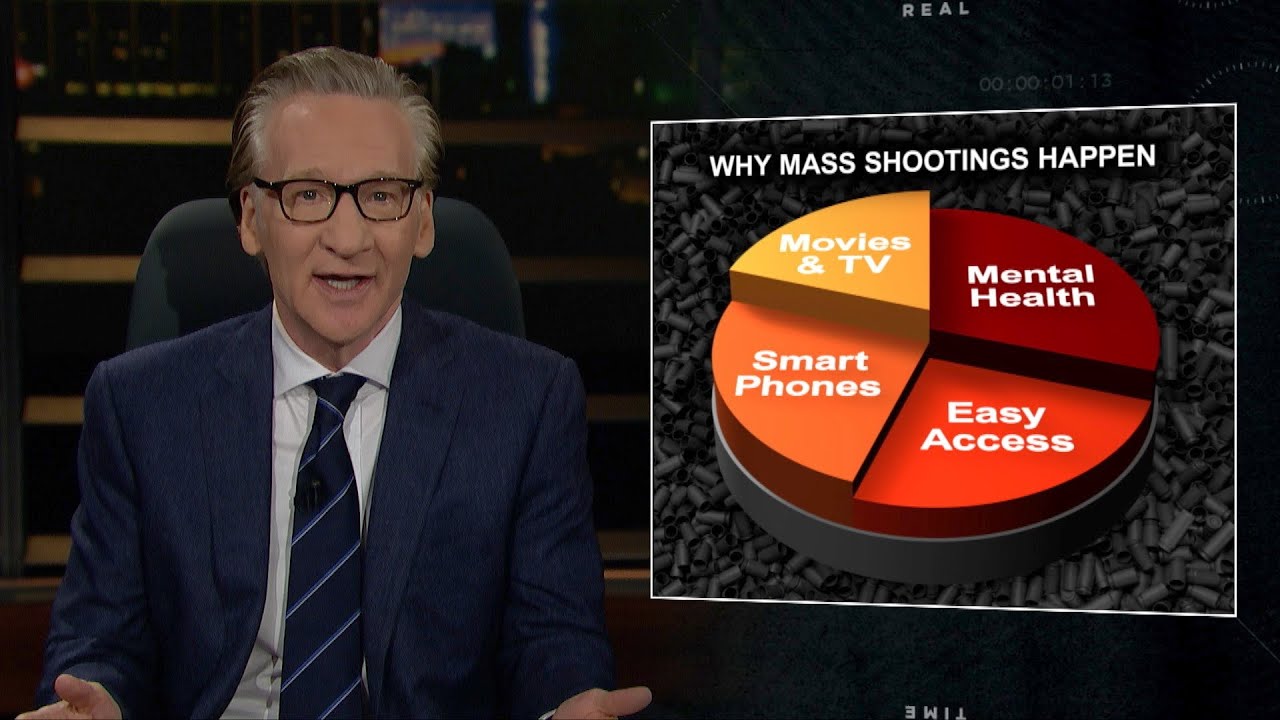

The argument over gun control comes down to this: one gun death at a time, 93 of them every day, more than 34,000 gunshot deaths every year (and most of those deaths—24,000—by handgun), according to FBI statistics. For teenagers like Amy, gun injuries are now an epidemic, the second leading cause of death among young people. According to a 1993 Louis Harris poll, one American parent in five personally knows a child who’s been shot.

A Tale of Two Cities

In Vancouver, Canada—just a scenic, three-hour drive from Jenny Wieland’s home—the terrible numbers change. Far fewer people live and die by the gun. Scientists have been studying the reasons for that difference, but parents like Maggie Burtinshaw know them by heart. Her son was just 19 when he was gunned down in Vancouver by a 13-year-old boy who, as he told the police, was acting out a plot he’d seen on TV. The boy hid in a department store until after dark, then stole two rifles from an unlocked case and fired them both at the first person he saw, Maggie’s son, Eddie.

But that was 1974. Maggie mourned—and then she got moving. “I didn’t want it to happen to another mother’s son,” she says. She lobbied and worked hard with the Vancouver chapter of her country’s Coalition for Gun Control. By 1978, tough new laws were in effect. Since then, gun deaths have gone down in Canada … but not in the United States.

Sisters in sorrow, Jenny and Maggie live in sister cities, as alike as any two large cities can be. Seattle and Vancouver sit on opposite sides of the U.S.-Canadian border, but they share a common geography, climate, language, and history. They resemble each other more than they do other cities in their own countries. Seattle is safer and more peaceful than most big cities in the United States; Vancouver has a higher rate of violence than most other Canadian cities.

Both are large Pacific ports. Both are famous for their physical beauty and excellent quality of life. Their residents have similar levels of schooling and similar family incomes. Both are overwhelmingly white cities, with black and Hispanic minorities in Seattle and Asian minorities in Vancouver. They share many cultural values and interests. Residents of both cities have a fondness for coffee bars, and they even watch the same TV shows.

But there is a life-and-death difference. According to a seven- year study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1988, you are almost eight times as likely to be assaulted with a gun in Seattle and five times as likely to be murdered with one.

A team of scientists—led by Dr. John Henry Sloan of the Harborview Medical Center in Seattle—put the two cities under a microscope. The economies, the demographics, the daily behavior of people were too similar to explain the difference in the death toll. One possible cause after another was eliminated, until the researchers were left with only one plausible explanation: Guns are reasonably restricted in Vancouver, but they are out of control in Seattle.

As the cities go, so do the two nations. In the United States, one in two homes has at least one gun in it; in Canada, it’s one in four. Canada has not been disarmed; its citizens own hunting rifles and shotguns at about the same rate as Americans. Under a strict law, though, Canadians own only one-tenth as many handguns, the weapons that can be hidden in purse or pocket, the weapons that target and kill more people than any other. In 1992, Canada also put stiff restrictions on military-style assault weapons; only four American states have similar laws. In the U.S., the homicide rate is 9.8 per 100,000 people; that’s three- and-a-half times the Canadian murder rate of 2.8 per 100,000.

The Threat from Angry Drivers

In Seattle, Cynthia Coston knows all too well what the U.S. numbers mean. On the spring night of April 17, 1993, she was driving home with two sleepy little daughters in the back seat. Her path was blocked by a black Mustang that was stopped in the middle of the road. She waited, unable to pass, and then she honked her horn.

When the Mustang finally moved, turning a corner, Cynthia drove on. She didn’t see the 9mm semiautomatic pistol that was being aimed at her car. She did hear the odd, popping noises— “like firecrackers,” she thought at first. But then, in the rearview mirror, she saw Loetta, just turned nine, slumped down. Pulling over, scrambling into the back seat, she gasped at the small hole in her daughter’s temple, made by a bullet that had come through the back window. “Dear God,” the mother prayed. While a passerby phoned for help, she held the dying child in her arms.

To everyone who knew her, Loetta was “a special little girl,” lively and curious, with saucer eyes and a megawatt grin. To those who are keeping count, she was the second child to be shot in Seattle that year by someone who was angered or threatened by the simple honking of a car horn.

In Vancouver, Sandra Wahlgren is also the mother of two little children. Happily, she visits the local parks and drives around town with them. She shudders at the Coston tragedy—she has always worried about the firepower across the border. “For years,” she says, “we’ve been warned not to honk our horns when we go to Seattle. Because a driver might get angry. And in Seattle, he might have a gun.”

If Vancouver feels safer than Seattle, it is not because its people are naturally more peaceable or law-abiding. The two cities have similar rates of burglaries, robberies, and simple assaults; similar rates of arrests and similar punishments for criminals. They have almost identical rates of aggravated assaults with knives, blunt instruments, or fists. But Seattle’s assault rate soars when you add in its much higher number of assaults with guns. In the same way, the two cities have similar rates of murder by various means—until you count the fivefold higher risk of being killed by one of Seattle’s easily available handguns.

Punctured Myths

The twin-city figures puncture one of the many myths about guns. Groups like the powerful National Rifle Association (NRA) often argue that guns don’t kill people; people kill people. They insist that if would-be attackers don’t have guns, they will come at you with some other weapons. But the figures show that that isn’t happening in Vancouver. Even if it were to happen, citizens would still be safer; a shooting is five times more likely to be fatal than a stabbing.

In Vancouver, guns are hard to come by. There’s a 28-day waiting period for a Firearms Acquisition Certificate that allows you to buy rifles and other long guns, and additional stiff requirements for “restricted weapons” like handguns. “The more we restrict handguns, the better off we are,” says Gordon Campbell, mayor of Vancouver. “Anyone who thinks we need a free flow of guns just doesn’t understand how modern society works.”

In Seattle, Mayor Norm Rice also supports gun control. But here, there’s only a five-day waiting period for a quick background check. To buy a handgun, you’re supposed to be 21 or older, but that hasn’t stopped the teenagers of that city. More than one in three Seattle high school students—according to a 1992 Journal of the American Medical Association survey by Drs. Charles Callahan and Frederick Rivara—say they have easy access to handguns. (Nationally, according to a Harvard School of Public Health survey, the figures are even more explosive; 59 percent of U.S. children in sixth through twelfth grades say they “could get a handgun if they wanted one.”) In Seattle, 11 percent of the boys say they own their own handgun, and one-third of those gun owners admit they’ve fired at another human being. The young handgun owners are not just gang members, drug users, or school troublemakers. Many of them are “nice kids.”

|

The Cost of 200 Million Firearms Every year, more than 24,000 Americans are killed with handguns in homicides, suicides and accidents. In 1990, 37,155 people died from firearm wounds in the U.S. compared to 13 firearm deaths in Sweden, 91 in Switzerland, 87 in Japan, 68 in Canada, and 22 in Great Britain. The difference is that an estimated 200 million firearms are owned by private citizens in the U.S., including 67 million handguns manufactured for the sole purpose of killing people. Tim Wheeler, Peoples Weekly World, December 18, 1993. |

In Seattle, Joanne Wallace still mourns the day her son Gregg, 15, went out to play in the park with seven of those nice boys. Two of his friends had each filched a handgun from home. They passed the guns from hand to hand. Then one of the boys, just 13, the son of a minister, put a bullet in his .22 caliber pistol. He pulled back the hammer and shot at Gregg. “I just wanted to scare him,” he said later. But his aim was deadly, and Gregg, hit in the chest, died almost instantly.

The shooter was sentenced to just eight weeks in juvenile detention. His father, despite Joanne Wallace’s pleas to the judge, was not held responsible. “What’s a minister doing with guns?” the grieving mother asks. “What’s anyone doing with them?” She’s now working for a law that already exists in a few other states, a law that would hold parents responsible for a gun that’s not kept safely and falls into the hands of a child.

Instead of a law, gun groups like the NRA argue for training in firearms safety. But the boy who shot Gregg had taken such a course. “I’d like to tell people, ‘Don’t do it. Don’t touch that gun,”’ he said recently. “But I don’t know if they’d listen.”

Fatal Gun Statistics

His own parents may not be listening. They still believe “responsible people” have a sacred right to own handguns, though they say people with children should “think twice.” They, too, knew all the safety rules but, as a recent study shows, people who’ve been through a training course aren’t any more likely than others to keep their guns safely unloaded and securely locked up.

The minister and his family have become part of a fatal gun statistic. According to a University of Washington study by Drs. Arthur Kellerman and Donald Reay, if there is a gun in the home, it is 43 times more likely to be used to kill its owner, a member of the family, or a friend than to kill an intruder. Some people own guns for sport, some for self-protection. Yet out of the 34,000 gun deaths in America each year, fewer than 300 are listed as “justifiable homicide,” the only category that could include shooting a burglar, mugger, or rapist.

Gun fans don’t like those figures. They argue that they don’t include the large numbers of private citizens whose lives were saved because the intruder or attacker was scared off by a gun. That’s true. They also don’t include the people—innocent citizens or guilty burglars and rapists—who are wounded by guns. For every gun death, there are four to 10 gun injuries.

The wounded and the maimed are rushed to emergency rooms. In Vancouver, it could be the one at Vancouver General Hospital, but gun injuries are a rare event there. When Dr. Ron Walls checked the records, he found only a dozen for all 1992.

In a Seattle emergency room, they might see that many in a week. “It’s not uncommon to see a number of shootings in a single day,” reports Chris Martin, nurse-manager for the Emergency Trauma Center at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. “They come day and night now. They are the innocent and the not-so-innocent.”

Among Harborview’s recent patients was a young man named Isaac Rollins. On June 1, 1993, he was showing off his new semiautomatic pistol. The handgun made his girlfriend nervous, and he wanted to demonstrate to her how safe it was. He handed her the loaded clip, then pointed the gun at his own head. But there was still a bullet in the chamber, and when he pulled the trigger, it entered his brain.

Miraculously, he survived and is recovering. Still, gun injuries are expensive for all of us. The overall cost to the American health-care system is $4 billion a year. Everyone pays for it in taxes or increased insurance costs or dollars not spent on other health care.

The Real Enemy

In Seattle, one horror story follows another. An attorney is gunned down in his office by an angry husband, taking revenge for a divorce settlement he didn’t like. After an argument, a neighbor opens fire on the family next door, killing the mother, wounding the father, and leaving a three-year-old boy paralyzed. A pharmacist, Evelyn Benson, holds the record for staring down the barrel of a gun—her pharmacy has been subjected to 29 armed robberies.

The unknown criminal frightens us, but he may not be the real enemy. A growing body of research shows that the majority of murder victims are not killed by strangers intent on committing a crime; instead, the trigger is pulled by someone they know. And that’s especially true of women.

In recent years, more and more women have been arming themselves. The world seems more violent, the streets more dangerous, and gun manufacturers have appealed to that growing fear. They have targeted women as a new market, producing guns that are smaller, even prettier, and advertising some of them as “dishwasher safe.” Yet according to another study by Dr. Kellerman, sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control, more than twice as many women are shot and killed by their husbands or lovers than by strangers. Usually, it happens in the midst of an argument; he gets angry and he gets a gun. Sometimes, it’s the very gun she bought to “protect” herself.

The American debate over gun control is becoming more heated. On one side, groups like the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence—an umbrella organization with chapters in Seattle and other U.S. cities—want laws that would limit the sale of high- risk handguns and assault weapons. On the other side, groups like the NRA argue that good people need those guns to protect themselves against the bad guys. It’s true that, law or no law, some criminals will always manage to steal, smuggle, or somehow get their hands on guns. Today, one of their best sources is law-abiding people whose guns are lost or stolen.

The fear is real. Even in Vancouver, some people wish they were safer. Ray Eagle, who heads the city’s Coalition for Gun Control, points to Great Britain and Japan, two countries where the laws are stricter, guns are fewer, and murders are rarer than in both the United States and Canada. Opponents of gun control prefer to look to Israel and Switzerland, two countries with very high rates of gun ownership and very low rates of murder. But international comparisons don’t prove very much for either side; the picture is confused by the different cultures and economies.

A Cultural Difference

Opponents of gun control also like to quote from a study by Dr. Brandon Centerwall of the University of Washington. He compared the states and provinces that are neighbors along the U.S.- Canada border. Unlike the Seattle-Vancouver study, he found no connection between the number of guns and the number of homicides. Some scientists, though, feel the Centerwall study is seriously flawed, mostly because he didn’t include the big cities where so much American violence takes place. To make the states and provinces more “alike,” they say, he focused on the lower- risk rural areas, typical of Canada, and excluded such armed camps as Detroit and New York City from his comparison.

Americans have a firm grip on the handgun trigger. “A gun is a symbol of power. It is the great equalizer,” explains Dr. Joyce Brothers. “And if you’ve ever watched a man play with his gun, clean it and polish it, you know that it’s also a phallic symbol. That may be why they keep making guns bigger, more powerful, more capable of shooting more bullets. It’s that old school- yard game of‘mine is bigger than yours.’”

The gun carries the same symbolism in Canada, but there is a cultural difference. “We have different national myths,” explains Wendy Cukier, a history professor at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute in Toronto. “Your quintessential hero is the lone cowboy with his six-shooter. Ours is a figure of law, the Royal Canadian Mountie.

“Americans are passionate about individual rights and liberties. Canadians are more willing to restrict those rights for the common good. Your Declaration of Independence talks of‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ Our Charter of Rights talks of‘life, liberty, and security.’”

Meanwhile, the death toll mounts on this side of the border. Guns are the least regulated, least controlled consumer product on the American market. Every two years, more Americans are killed by guns at home than were killed in all the years of the Vietnam war. In 1992, for the first time in history, more people in Texas were killed by guns than were killed by cars.

Changing Opinions

Yet something is changing. For the first time, in a recent poll, most Americans say they favor some form of gun control. They are worried about shattered lives and grieving families; and gunfire in the streets, the schools, the post offices, and fast-food restaurants.

In Vancouver, there is proof that gun-control laws can make a difference for people just like us. In Seattle, there is the voice of a grieving mother. “Someone’s right to have a gun,” says Joanne Wallace, “took away my right to have a son.”

Source: Claire Safran, “A Tale of Two Cities—and the Difference Guns Make.” Good Housekeeping, November 1993. Copyright ©1993 by Claire Safran.