Roman Games

Spartacus had a powerful star and a politically committed screenwriter. So how did Stanley Kubrick put his personal stamp on the film, asks Henry Sheehan?

by Henry Sheehan

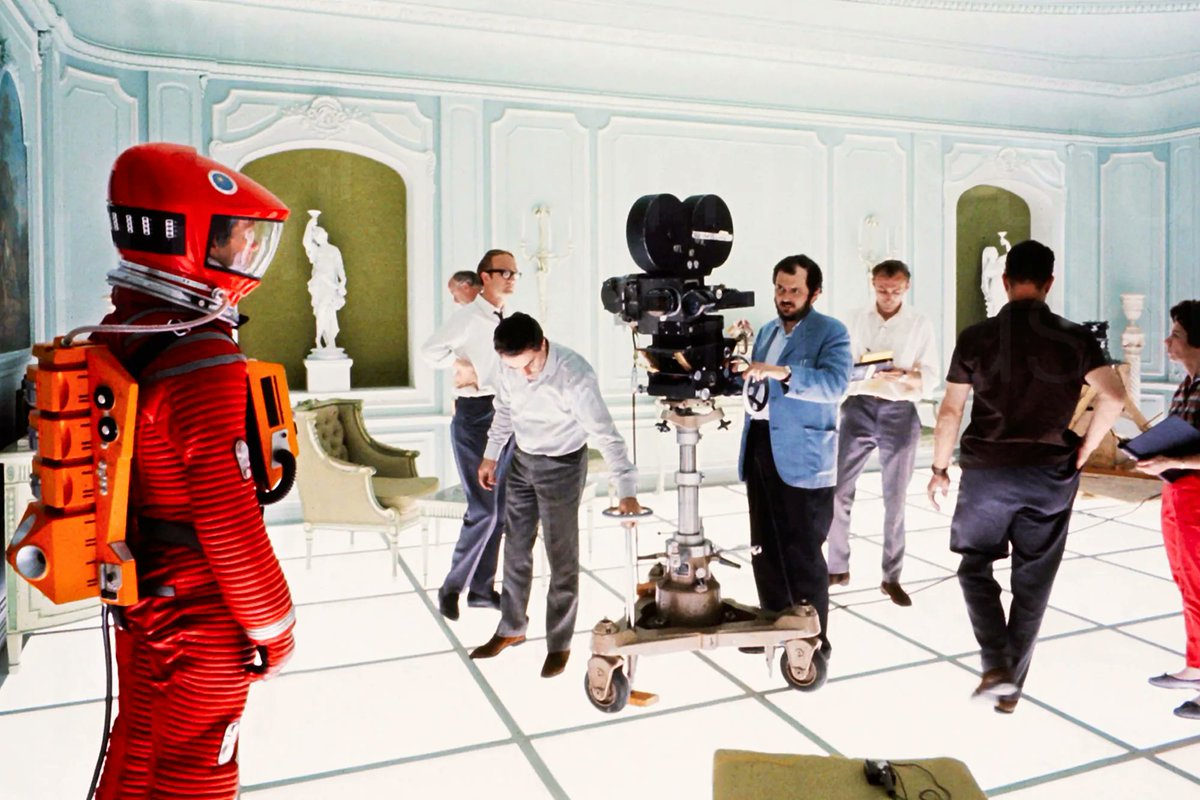

In Spartacus I tried with only limited success to make the film as real as possible but I was up against a pretty dumb script which was rarely faithful to what is known about Spartacus. History tells us he twice led his victorious slave army to the northern borders of Italy, and could quite easily have gotten out of the country. But he didn’t, and instead he led his army back to pillage Roman cities. What the reasons were for this would have been the most interesting question the film might have pondered… If I ever needed any convincing of the limits of persuasion director can have on a film where someone else is the producer and he is merely the highest-paid member of the crew, Spartacus provided proof to last a lifetime.

—Stanley Kubrick, quoted in Kubrick by Michel Ciment

Monday morning, the principals, in costume, were sitting in the balcony of the gladiator arena. Rumours were flying. I took Stanley into the middle of the arena. ‘This is your new director’. They looked down at this thirty-year-old youth, thought it was a joke. Then consternation – I had worked with Stanley, they hadn’t. That made him ‘my boy’. They didn’t know that Stanley is nobody’s boy. He stands up to anybody.

—Kirk Douglas, The Ragman’s Son

The tremendous box office success of Spartacus was a wave which propelled Stanley Kubrick on to the golden shores of bankability. A young man of thirty-one, the director demonstrated that he could handle the most expensive and difficult of projects and come up with a broadly appealing hit, a situation which allowed him to go on to make films which were increasingly idiosyncratic, while still remaining among the surest of box office successes. But there is much in Spartacus which did not originate with Kubrick and ultimately was beyond his influence. So the question remains: what is Kubrick to Spartacus, and what is Spartacus to Kubrick?

Certainly when Kubrick began directing Spartacus, the potential authorship of the $12-15 million epic was in dispute. After completing the opening sequence depicting the future rebel leader Spartacus under Roman bondage in ancient Libya, veteran director Anthony Mann had been dismissed. The reasons for his sacking are still shrouded in mystery, though to judge by the vivid footage that still opens the film, these may have amounted to being too sure of his own vision for the comfort of his colleagues and employers.

These roles were joined in star Kirk Douglas, who with his partner Edward Lewis was producing the film under their Bryna Productions banner. Douglas had very definite ideas about the film’s presentation and was not shy about sharing, or even enforcing, them. The film’s huge price tag also guaranteed close supervision from the executives at Universal, who had other problems at that time. The studio’s ownership was up in the air, a situation that was settled at some point during the shoot when the MCA agency took over Universal and Lew Wasserman went from being producer/star Douglas’ agent to his boss.

While this is a far from exhaustive list of the important players in the making of Spartacus, it does suggest from how many quarters power was exercised. The film’s programmatic politics, for example, are largely those of two Hollywood blacklistees, Howard Fast, the author of the (self-published) source novel, and Dalton Trumbo, the film’s screenwriter.

Even while serving the ten month sentence he earned by refusing to co-operate with the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Trumbo had started his guerrilla campaign against the blacklist, smuggling out a script to be sold under a pseudonym on the underground market. For Spartacus, Trumbo planned to use his first open credit in a decade both to break the Hollywood blacklist (a move pre-empted by Otto Preminger’s announcement that Trumbo would receive full credit for Exodus) and to reintroduce liberal-left discourse into mainstream Hollywood film-making.

Despite its ancient setting and occasionally tortured syntax, Trumbo’s script – or at least those portions which involve the active participation of Spartacus himself – is basically Depression drama, drawn from the traditions of the working-class lyricism of the New York stage and from Hollywood notions of heroism. Spartacus is a John Garfield-type character, the ultimate everyman fighting against the organisation, the mob, corrupt politicians, the big fix, or, as it happens, the patricians of Rome. Like the fliers in Thirty Seconds over Tokyo (1944), one of Trumbo’s most popular pre-blacklist scripts, Spartacus is the average man rising to the demands of historical necessity with heroic drive but personal modesty. He gathers his moral purpose not from who he is, but from whom he represents.

It is a character type completely foreign to Kubrick’s cinema. Even Kubrick’s previous feature, Paths of Glory, another Douglas vehicle, exhibits a mordant cynicism about the uselessness of resistance to great power rather than the sort of effusive optimism exuded by the eponymous hero of Spartacus.

Sexual trophies

The expectations aroused by the footage that opens the film, in which a largely mute Spartacus is discovered toiling under the Roman lash and the blazing Libyan sun, are of a typically intimate Anthony Mann saga about a man’s brutal struggle against a hostile physical environment. Yet even after the still silent Spartacus is transported by Peter Ustinov’s wisecracking slave dealer Batiatus into the walls of a gladiatorial boot camp, it’s hard to detect an emerging authorial hand.

The scenes of the slaves being run through an arduous training course are among the film’s best, but they are specifically masterpieces of montage, of economical narrative – not a Kubrick speciality. The first forty-five minutes of Full Metal Jacket provides an interesting comparison. In these scenes of raw recruits being turned by a US Marine drill instructor into killing machines, Kubrick does use an extended montage method. However, his individual shots are not so much traditionally compact building blocks as self-contained moments, tracking shots which emphasise temporal and spatial context in a way that mocks the military activity of the boy soldiers.

The irony in the training scenes in Spartacus is both gentler and plainer; it is the use of the training, not the training itself, which is cruel, and clearly the slaves will soon turn their new skills against their masters. The rhythm of the scene would never recur in any Kubrick film, and though the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, credits Kubrick for its overall pace and shape, it does not seem out of order to attribute this particular sequence to Lawrence himself. Similarly, the scenes in which Spartacus’ purity is tempted by the enforced availability of the slave girl Varinia (Jean Simmons) are further demonstrations of Trumboesque idealism.

But with the arrival of a group of pleasure-seeking Roman nobles headed by Crassus (Laurence Olivier), Kubrick’s personal stamp becomes apparent. Although he is famous for his tracking shots, it is the two-shot which is most emblematic of Kubrick’s visual style. Usually a relatively spacious shot, in Kubrick it fixes a pair of conversationalists in constricted postures against which any deviation in gesture becomes doubly suggestive. Often the gaze of these talkers will be fixed outside the frame, or even unfixed, indicative of a mind concerned with objects far removed from the immediate visual field.

When Crassus arrives with his friends, they are immediately shown into Batiatus’ salon, where they begin to drink and to fume about the risk that their enemy Gracchus (Charles Laughton) represents to their status. Olivier, who revels in a melodramatic villainy throughout the film, is particularly emphatic in his moody, glassy stares into midspace. Thereafter, brightened by the prospect of a gladiatorial competition to the death, the two aristocratic women in the party—languorous and very contemporary caricatures of the idle rich—move outside, where they ogle the caged slaves. As Batiatus flutters around them trying to sell them worn merchandise, the two decadents are seen feasting their eyes on the sexual trophies outside the frame.

In its tactical deployment of watchers, watched, and a mediating third party trying to block the whole enterprise, it is a sequence that would be echoed in Kubrick’s next film Lolita. Beyond question the director’s best work, Lolita consists largely of a series of two-shots arranged by the protagonist, Humbert Humbert (James Mason), in ardent pursuit of the nymphet Lolita (Sue Lyon). Finding himself beset with unwanted company, usually Lolita’s mother Charlotte (Shelley Winters), Humbert is constantly trying to move (sometimes literally) one or another character out of the frame and drag Lolita in. The space Humbert (and, he hopes, Lolita) inhabits is defined not so much by what it encompasses as by what it excludes: as with the Roman nobles, the unmanageable rest of the world.

Tracking his Lolita at a high school dance, Humbert finds his solitary regard of his prey constantly interrupted by Charlotte and some friends who are frantically trying to shift his gaze from a keenly desirable object to one less so. Humbert moves around the periphery of the dance floor – separated from it as if by a fence – finding new perspectives from which to watch. Invariably his lonely perch is invaded and violated, but his look remains directed outside the frame. This dance sequence, fluid and geometrically eloquent, is a more sophisticated and graceful version of the scene at the gladiator compound in Spartacus.

After freedom

Editor Robert Lawrence, who helped to supervise the recent restoration of Spartacus, has described how it became clear as the production went on that the figure of Spartacus became problematic once he had freed himself in a riot at the gladiator compound. After all, as Lawrence put it, a freed slave is inherently undramatic, his conflict having been resolved to his satisfaction.

Despite the sheer immensity of the scenes involving Spartacus at the head of his increasingly huge slave army, the film-makers do seem to have stooped to certain tricks at times to maintain audience interest. Sometimes it involves no more than inflating standard scenes – letting Spartacus romance Varinia after he finds her bathing, for example. Other devices are more obvious, notably the two appearances of a bejewelled and robed Herbert Lom as a flamboyant pirate who helps to arrange the slaves’ escape from Italy.

As the film progresses, the emphasis shifts to the Roman response to Spartacus, reducing him almost to a motif represented within the character of Crassus. Already in Trumbo’s construction and Douglas’ broad playing a representational figure of freedom and the ‘common man’, Spartacus becomes a quite different figure in Kubrick’s hands – more a symbol for chaos, for everything that is unmanageable. He is Crassus’ insecurities come to life and a nightmare of the Roman polity.

Spartacus, the rebellious outsider and force of disruption, and Crassus, the repressive beneficiary of order, are the prototypes for all the Kubrickian protagonists and antagonists to follow. Only in Lolita did Kubrick manage to combine the two figures into one piquantly unresolvable paradox, and here he did it twice: in the figure of Humbert Humbert and in his evil double, Clare Quilty. Otherwise, the list of Kubrick’s heroes becomes a litany of Spartacuses (Keir Dullea’s astronaut in 2001, Malcolm McDowell’s hood in A Clockwork Orange, Jack Nicholson’s killer in The Shining, Ryan O’Neal’s adventurer in Barry Lyndon, Matthew Modine’s recruit in Full Metal Jacket) or Crassuses (nearly everyone in Dr. Strangelove, HAL the computer in 2001, the scientists and politicians of A Clockwork Orange, Lyndon’s stepson in Barry Lyndon, the telepathic boy in The Shining, the drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket).

Images of hell

What changes across the films more than the characters is Kubrick’s attitude, which becomes increasingly misanthropic. The two films before Spartacus, The Killing and Paths of Glory, are both distinguished by an air of futility, of calamitous efforts gone unrewarded. Paths of Glory, in particular, verges on the nihilistic. Largely composed of a series of tracking shots through trenches and banquet halls, this First World War drama concludes with an image of death: three men tied to poles, their bodies pierced by bullets from a firing squad. They have died for nothing, the film says, but human vanity and error.

This is the statement of a coruscating moralist, and if the conclusion coincided with Douglas’ intention, the ferocity of tone is clearly Kubrick’s. As the years went on, Kubrick began to hold his rebels and revolutionaries in the same regard as their oppressive opponents. If Spartacus is vaguely defined in an outline of hazy idealism, later Kubrick rebels would become nearly devilish in their stark outlines. In fact, the most recent image that Kubrick has left us is an image of hell, of young men singing a children’s song as they march from one wartime atrocity to another, womanless and childless.

What a difference from the end of Spartacus, in which the line of crucified innocents is mitigated by a man, a woman and a child heading for the horizon. Kubrick may have wanted to turn away from the kitsch implicit in such an image, but he may have turned away from much more besides.

Sight and Sound, August 1991, pp. 22-25