The title of Stanley Kubrick’s latest film, A Clockwork Orange, alludes in two different ways to something circular or spherical that is closed on itself and spins. We can immediately see, even though we think we are in the future, that we are at some considerable distance from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and from Kubrick’s vision of huge leaps forward in terms of progress, the latter film perhaps modeled on a spiral, but definitely not on a circle.1

Circular Misadventures: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange

by Jean-Loup Bourget

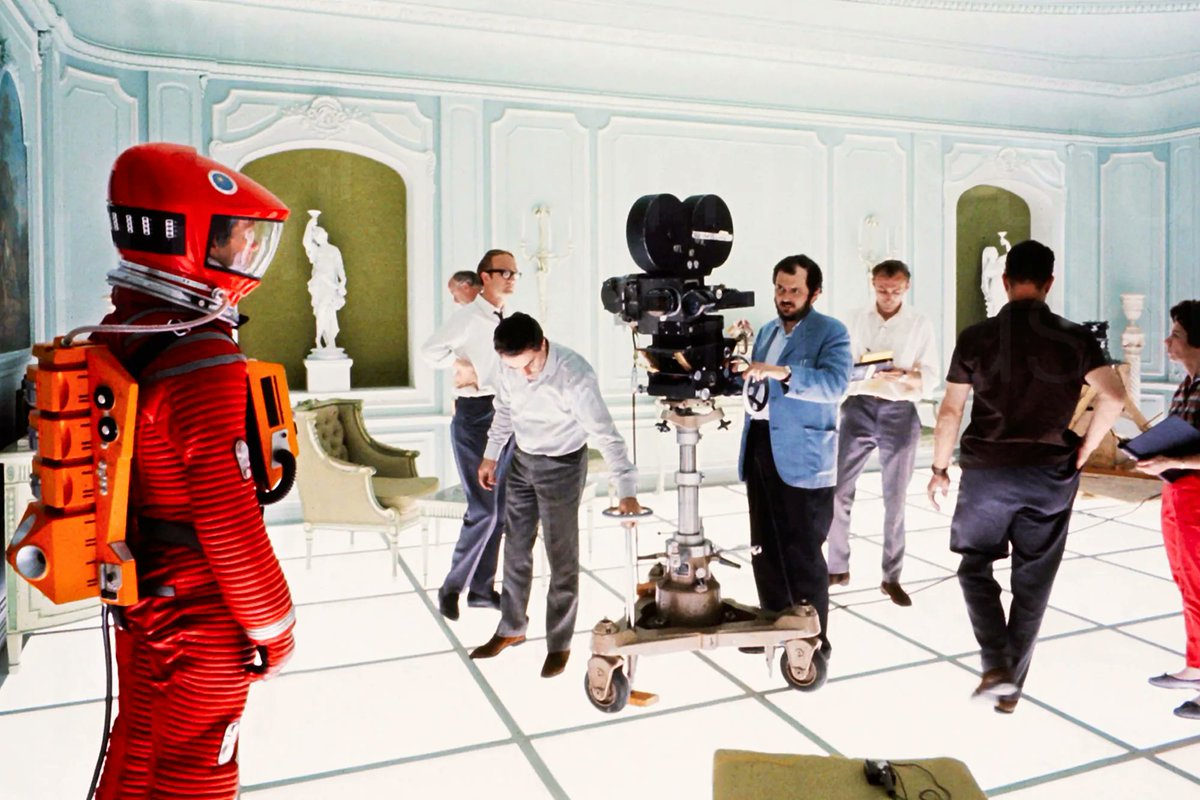

Stanley Kubrick the most controversial of contemporary directors, who was often reviled by the press, has always found strong support in the magazine. For the fiftieth anniversary and five-hundredth issue of Positif, he was voted the favorite director and 2001: A Space Odyssey the favorite film of the last half-century by eighty-seven past and present contributors.

The first article on his work, a review of The Killing, seen in Belgium one year before its French release, was written by the novelist Jacques Sternberg, who, a decade later wrote Je t’aimeje t’aime for Alain Resnais. Positif also published two rare long interviews with Kubrick on 2001 and A Clockwork Orange. The latter was accompanied by two essays, one by Robert Benayoun, the other by Jean-Loup Bourget, which is translated here.

* * *

The circularity of A Clockwork Orange is particularly evident in its plot, which includes incidents such as: A (the beating up of the Irishman); B (the wrecking of the Alexanders’ home); C (Alex in his parents’ apartment); D (the fight between Alex and Dim). These are all repeated again in the following order: C (Alex returns to his parents); A (Alex is recognized by the Irishman),- D (his former droogs, who have become policemen, find Alex),- and B (Alex’s second visit to Mr. Alexander). There is also the ironic “healing” of the hero/narrator at the end of the film, a healing that is made tangible through its similarity to (rather than a reversal of) the reprise. Whereas the incidents in the two previous series are opposed like the two halves of the clock face or the orange, at the end of the film, conversely, we have gone around the circumference and returned to the same type of erotic vision that Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony evokes for Alex.

Stylistically, there are many circular misadventures: a round bowler hat on a round head, the single eye with a fringe of eyelash drawn on Alex’s wrists (making the eye a clockwork wristwatch); later, Alex’s eye, which he is forced to keep wide open with clips that ironically recall his false eyelashes, seems to be a replica of his round head with spiky hair; mothballs or billiard balls,- the prisoners in a circle,- women’s breasts, particularly Mrs. Alexander’s, which they “peel” like an orange, etc.

But the film is circular in other more subtle ways. Let us suppose; for example, that the moviegoer becomes disgusted by the violence in the first part. The next part of the film teaches the audience that reacting to violence through physical disgust (whether caused by drugs, a conditioned reflex, or simply education) is an amoral attitude that is extremely suspect and must be rejected. This presents the audience with an ironic contradiction. (I am not addressing here those in the audience who identify and sympathize with Alex, which is clearly the case for much of the young male public. This is a rather serious situation, because they don’t get the basic irony of the film and can only maintain their fascination for Alex by forgetting that their hero is ridiculous for the rest of the story, including the ending.)

Let’s take a more specific example. When Alex goes into treatment the first time, treatment to make him “good,” he mentions that the film he was shown, a savage beating, was part of the tradition of Hollywood realism (the reference to Hollywood is not made in the Anthony Burgess novel), and he comments: “It’s funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.”

By leaving Burgess’s sentence in Alex’s mouth, Kubrick himself tends to destroy the illusion of the film’s reality (in this instance, an unreal reality because it has to do with the future, but never mind) after establishing it in the opening. Although we first believed in the existence of the Korova Milkbar because of its beauty and strangeness, and the disquiet it elicited in us and in the world of A Clockwork Orange, our belief is challenged within the film itself.

Any public that applauds violent or erotic passages therefore fails to understand that the subject of the film is the audience itself. The real subject of A Clockwork Orange is, in my view, neither the futuristic vision of the first part, nor the largely traditional satire of a world we know well because it is our world (in the second part). A Clockwork Orange is not a remake of either 2004 or Dr. Strangelove, but rather an ironic game of reflections between the public and the object of the public’s fascination (sex, violence).

The film is a mirror held up to the audience in which they willingly recognize themselves without necessarily believing that they are being caricatured or even ridiculed by Kubrick. Something similar happened in Bertolt Brecht’s The Three penny Opera, about which Hannah Arendt says, in Origins of Totalitarianism, that the play presents gangsters as respectable businessmen and vice-versa, an irony somewhat hidden from any respectable businessmen in the audience who considered the play to be a penetrating view of the realities of life. Most people felt that the play was an artistic acceptance of gangsterism.

It is on the stage of a theater, to the music of Gioacchino Rossini’s Thieving Magpie that the third sequence of A Clockwork Orange opens. Billy Boy and the members of his gang, undressing a girl to rape her, look like nothing more than robots (giant marionettes are indeed present on the stage): the organic hemisphere of the film (orange, violence, and sex) is reduced to the clockwork hemisphere (pendulum, brainwashing). The music and the theatrical setting, nicely framed by red curtains, have a distancing effect,- likewise, in the next sequence, the fight between the two gangs is outrageously and deliberately choreographed like a ballet. It is clear that Kubrick is telling us that we are watching stuntmen and not hoods. In short, the satire touches lightly on its apparent object (the world of tomorrow or today) and then returns against itself and shatters its own mode of expression.

This clarifies the many references in A Clockwork Orange to other films. Is the inordinate ambition of A Clockwork Orange to be to the history of the cinema writ large what Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man is to the Western? There is, for example, the physical resemblance—basically established through makeup, i.e., artifice—between Alex and the young “hero” of Luchino Visconti’s The Damned. The modern cinema, with its undeniable predilection for topics dealing with fascism, would appear to indicate a genuine progression from The Damned to Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist and then to A Clockwork Orange. The general preoccupation with historical fascism is 124 underscored by the use of the old German films that Alex is shown when he is in treatment. If Visconti’s Wagnerian style is riddled with futuristic flashes of brilliance, which become irreverent in Bertolucci, then the process becomes systematic with Kubrick’s strokes, which are more like collage or Pop art, though he uses more intellectual materials than the latter (quite literally, the “Pop” Christs in Alex’s room are filmed in pure meccano montage a la Sergei Eisenstein). It is clear that Kubrick is close to his European counterparts, if only through the musical complexion of his work. In addition, it struck me that there was an echo of Bertolucci Jean-Louis Trintignant finding Pierre Clementi in the Roman lower depths) in the scene in which Kubrick has the tramps hitting Alex with sticks.

Alex’s mental flashes, or erotic-sadistic visions, are straight out of the movies. One of the obvious examples is when he is reading the Bible in prison and first imagines himself as a Roman centurion whipping Christ, and then as an Old Testament king enjoying the repose of a warrior, voluptuously lying among grapes and Hebrew servant girls with pink breasts and gazelle eyes, redolent of Scheherazade. The sequence is reminiscent of a film by Cecil B. DeMille and recalls the old idea that the public only went to see Bible movies to sate otherwise illicit desires. Here A Clockwork Orange gives people whips to have themselves beaten: will the public be applauding a satire or simply getting an eyeful?

At other times, the doings of the four droogs lead us simply to the extreme conclusion of a clockwork logic, like that of the Beatles in Help! or of Gene Kelly and company in Singin’ in the Rain, or the Marx Brothers: it’s Harpo with the scissors just before Mrs. Alexander is raped.

It would similarly be appropriate to examine a number of the relationships between A Clockwork Orange and Kubrick’s earlier work, which is not immune from the general atmosphere of parody. The clown masks worn by the hooligans are an old trick from gangster movies, and Sterling Hayden wore a clown mask in The Killing. The mechanisms of political oppression were analyzed in Spartacus. Here, no one can take seriously the absurd dilemma between the hoodlums and the police state (because the two are interchangeable) or between reactionaries and liberals (also interchangeable), the liberals tending to be rich, unprincipled, and full of contempt for “the masses”: these are merely variations on the theme of the mirror or the circle, if you will. Everything is an echo of something else. Mr. Alexander as a double hypocrite of Alex, who has been made temporarily allergic to the suggestions of Ludwig van by the administration of the Ludovico (treatment) drugs. As for Mr. Alexander, the doorbell at his “home” plays (in the film) the first few notes of the Fifth Symphony, and as he is savoring his vengeance after having Alex locked up, he looks like a living bust of Beethoven.

At the end of the film, in a hospital setting, when the almost resuscitated Alex has a stereo delivered to him as a kind of settlement of his account with the Ministry of the Interior/Inferior, the scene, stylistically and thematically looks like an absurd echo of 2004: it is Keir Dullea having crossed over after death and become a Superman in his rococo apartment, with his new companions keeping him well fed and soothed by music. Insofar as A Clockwork Orange is a satire, it resembles Dr. Strangelove, but its eroticism and evocation of the world of the nadsats, or teenagers, in opposition to adults, remind us more of Lolita. In the record store displaying 2004 posters, two Lolitas suck on phallic soothers, only one of which is in erection: a barely veiled allusion to the image of Sue Lyon sticking out her pink tongue. (In passing, we regret the failure of the next scene, in which Alex and the two nymphettes make love over and over again in speeded-up action, to the sound of the William Tell Overture, a sequence that is too explicitly mechanistic and so distanced from the audience as to be like burlesque. It suffers considerably in comparison to the equivalent scene in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup.

Kubrick’s intention is thus not for the audience to identify with Alex, but to see retrospectively that they are in the same situation as Alex, if they are to believe what they are watching. When he sees that Alex has been cured, the Minister introduces him to his public exclaiming, “But, gentlemen, enough of words. Action speaks louder than. Action now. Observe, all.” Once again, the expression, from Burgess’s novel, takes on a different tone in a filmic context. Some William Tell music once again introduces the commedia dell’arte that follows: Alex licks the boots of a brutish and well-dressed person (a bolshy big chelloveck), grovels at the feet of a naked devotchka (girl), a futuristic apparition with long platinum hair and tanned groodies (breasts), and then the two salute the audience professionally and formally, indicating that Alex has been the ridiculous victim of a staged scene. (He, of course, gets his revenge in the mental flash that closes the film. We see him making love in slow motion with a girl whose arms and legs are sheathed in black. Hollywood yet again: the snow is artificial, and the audience, dressed as if they were in the Ascot sequence of My Fair Lady, applauds Alex’s performance. In his own eyes, Alex’s eroticism is mostly a show.) But what about us? Our fascination for the opening of the film—or for the apparition of the platinum blonde—is also frustrated and even ridiculed.

Frustration is one of the key themes of A Clockwork Orange. We find ourselves here in the middle of a satire that is no doubt most interesting, a world in which art is no longer a sublimation of sexuality, but merely a stylized representation of it, not metaphorical, at the same time as morality continues to be theoretically attached to an obsolete Puritanism. Among these stylistic and satirical successes I would include the set of the Korova Milkbar, with its furniture shaped like naked women whose breasts spout the milk of artificial paradises (here, as in the scene in which Mrs. Alexander is raped, Kubrick was able to find the perfect visual equivalents for the teenagers’ obsession for breasts in Burgess’s novel),- there is also the Alexanders’ “home” (where Mrs. Alexander plays the same purely decorative role as the objets d’art, whereas her husband spends all of his time playing the pseudo-intellectual),-Alex’s room, in which a phallic snake makes love to an obscene drawing, and, in particular, sated with provocative but evasive sexuality (intellectualized, and thus maintaining its status as an objet d’art, and hence untouchable), the Cat Lady’s house, the theater for the symbolic battle between the phallic sculpture (literal sexuality) and the bust of Beethoven (sublimated sexuality). The Cat Lady is ritually pierced, and Kubrick, rightly renouncing the false realism of spilled blood, cuts to the geometric garish mouth of a painting.

At other moments, the satire plays on the juxtaposition of stylization and realism. Sometimes this succeeds (for example, in the futuristic and highly British dress of the four droogs), but sometimes it is less satisfactory,- for example, one does not know quite what to think of Alex’s parents’ apartment, not only the contrast between his mother’s acid wigs and the English tea and cakes, but also the atrocious nudes hanging on the walls. The hideous colors are no doubt deliberate, but nonetheless hideous, coming up considerably short of style.

I would criticize the film for being merely realistic and failing to stylize the character of the drunk who sings “In Dublin’s Fair City” and in particular the long prison sequence, which is admittedly effective, but whose atmosphere is more evocative of the 1930s than the 1980s. Kubrick’s intent was no doubt for the prison to resemble a gigantic clock, but time does not go by very quickly there. The episode is saved in extremis by the visit from the Minister of the Interior, ironically accompanied on the soundtrack by Edward Elgar’s “Land of Hope and Glory,” closing on the procedures followed by the warder, which are performed like a clockwork mechanism.

Burgess’s novel had only one level upon which he could distance what was happening and make it humorous, namely, the nadsat language. Kubrick’s film does more than keep the language,- it also increases its expressive power by giving it the voice of Malcolm McDowell speaking to his only and faithful friends, an imaginary plural for a reader, with the voice of the narrator now aiming directly at an audience in a movie theater. At the same time, Kubrick strengthens the effect of the distancing with the veiling device of the off-screen voice and a multitude of other veils: music especially, sometimes classical, sometimes electronic, sometimes both together (the Ninth interpreted by Walter Carlos), used ironically rather than its heroic use in Space Odyssey. But also visually, by distorting things with wide-angle lenses, which are used frequently, and with the style of play, grimacing and neurotic, of Deltoid drinking water through his dentures or Mr. Alexander, bright red, serving Alex drugged Bordeaux. The use of these many veils strengthens the impression of the falseness of the film as an object, and by the end what remains is the audience’s basic frustration, sitting there as voyeurs and powerless, but laughing about their own fate.

1 A brief summary of A Clockwork Orange would be useful here. We are in England in the not-too-distant future. Alex, the hero/narrator, is the leader of a gang of teenagers known as droogs whose interests tend toward extreme violence and rape. We see the gang in action under a number of appropriate circumstances. Alex has a passion for Beethoven, which acts as a powerful stimulant on him. Unhappy with him, his acolytes turn him in to the police. In prison, he learns that the government is experimenting with releasing criminals after giving them medical treatment (the Ludovico treatment). He volunteers and becomes virtuous through conditioned reflexes. After being granted his freedom, he becomes the victim in a string of retaliations and falls into the hands of the opposition, which wants to use him for political purposes, he escapes death by the skin of his teeth, is “healed” by the government, and returns to being vicious again, and even more brutal than ever. A word about the language, nadsat: the slang used by Alex and all the adolescents of his era (nadsat = teenager). The language is largely based on London Cockney rhyming slang; he borrows many words from Russian, and sometimes combines them with English the way Lewis Carroll or James Joyce did with “portmanteau” words.

Positif, No. 136, March 1972