by James Naremore

Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick were child prodigies — Welles a theatrical wunderkind and Kubrick a teenage chess master and photographer for Look magazine—and both became iconic representatives of the cinema of the auteur. Both worked on the borderland between Hollywood and the art film, both made the same number of feature pictures, both directed two excellent films noirs, and both were virtuosos of depth of field photography and the long take. Both used radical distortions of the wide-angle lens to give the world a bizarre appearance, and both encouraged unorthodox acting styles— in Welles’s case an overheated, theatrical technique combined with carefully orchestrated overlapping dialogue, and in Kubrick’s a systematic oscillation between over-the-top mugging and almost Beckett-like minimalism. Both were attracted in subtle ways to nonrealist forms of narrative—Welles to the table and Kubrick to the fairy tale. Both were caricaturists and satirists (Kubrick more consistently than Welles), and the emotional quality of much of their work derives from the same family of affects: the darkly humorous, the absurd, the surreal, and the grotesque. Both died at age seventy.

There are nevertheless significant differences between the two. Welles’s grotesque for example, is Shakespearean and festive, whereas Kubrick’s is anxiety-ridden and laced with shock effects. Welles loved comedy and once boasted—stretching the truth—that he was the uncredited author of more than a third of the script for Howard Hawks’s I Was a Mule War Bride (1949). His magic act involved comic impersonation; many of his unfilmed scripts—The Unthinking Lobster, Une Grosse Légume, and Operation Cinderella—are comic and filled with amusing incidents; and even his most black-comic projects, such as The Landru Story, which became Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947), are different in tone from a movie like Dr. Strangelove (1964). Welles was a bon vivant and a gregarious personality, whereas Kubrick was a clever businessman and a steek perfectionist on the set. Welles made films about plutocrats or kings, and his comedy was often mingled with tragedy; Kubrick made films about scientists, soldiers, and the American nuclear family, only rarely dealing in tragic or sentimental emotions.

Despite these and other differences, the influence of Welles on the young Kubrick was palpable. When Kubrick’s The Killing was released in 1956, Time magazine claimed that its twenty-seven-year-old director had “shown more audacity with dialogue and camera than Hollywood has seen since the obstreperous Orson Welles went riding out of town on an exhibitor’s poll” (June 4, 1956). The Killing did, in fact, look very much like a Wellesian version of The Asphalt Jungle (1950)—it had bizarre camera angles, wide-angle distortions, mesmerizing long takes, a jigsaw-puzzle plot, a narrator who sounded as if he worked for News on the March, and even a screeching cockatoo. This may explain why Welles told a group of Spanish interviewers in the mid-1960s that of the directors he considered as belonging to “the younger generation,” Kubrick seemed a “giant.” “I believe that Kubrick can do everything,” Welles said. “He is a great director who has not yet made his great film. What I see in him is a talent not possessed by the great directors of the generation immediately preceding his, I mean Ray, Aldrich, etc. Perhaps this is because his temperament comes closer to mine” (Cobos, Rubio, and Pruneda, 22).

Whatever their respective temperaments, Welles and Kubrick were arguably the most sophisticated American-born representatives of artistic modernism in Hollywood. Several writers, among them Fredric Jameson, have argued that Kubrick’s late films are postmodern (Signatures of the Visible, 91-92), but if that term designates retro and recycled styles, waning of affect, lack of psychological “depth,” loss of faith in the “real,” and hypercommodification, then Kubrick was a modernist to the end. An avid reader of the Anglo-European and largely modernist literary and philosophical canon of dead white men (plus a great deal of pulp fiction and scientific literature), Kubrick maintained a lifelong interest in Nietzsche, Freud, and lung. Most of his films are rather like “late modernist” manifestations of the aesthetic detachment we find in Kafka and Joyce, or of the “cold” authorial personality in Brecht and Pinter; and no matter how much his work might have derived from Hollywood genres, it remained very close in spirit to the Euro-intellectual cinema of the 1960s. Where Welles is concerned, the connection with modernism is even more obvious. Certain aspects of Citizen Kane‘s symbolism and narrative structure are redolent of Kafka, its newsreel sequence and Hearst-like protagonist might have been inspired by Dos Passos, and its manipulations of time, memory, and point of view have evoked critical comparisons with Proust, Conrad, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald. Kane also synthesizes the major schools of European filmmaking before 1941—German expressionism, Soviet montage, and French surrealism—at the same time employing what Andre Bazin called a new filmic language based on the long take. Welles’s subsequent Hollywood films, no matter how diverse their genres or subjects, have similar qualities; The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) transforms Booth Tarkington’s genteel fiction into a darkly atmospheric Freudian drama, and The Lady from Shanghai (1948) uses a pulp novel as the basis for an exercise in surrealist eroticism and Caligari-like visual design.

Modernism was a distinctly international movement involving a kind of dialectic between American modernity and the European avant-gardes. Given its embattled relation with the economic, social, and political upheavals of the twentieth century, it also produced a great many exiles and emigres. In this context a comparison between Welles and Kubrick becomes especially interesting, for one of the most significant things the two have in common is that they both found it difficult, or at least undesirable, to work in Hollywood. They became American exiles, although we need to apply that term loosely, and to understand their careers we need to examine the different reasons why they lived so much of their lives abroad.

Even though Welles and Kubrick belonged to different generations, they both became emigres from the United States during the cold war. Welles enjoyed his most dazzling success in the Roosevelt years, and the seven pictures he produced and/or directed in Hollywood during the 1940s (one of them the incomplete It’s All True) were an outgrowth of his Popular Front activities in the previous decade. The decline of his Hollywood fortunes was overdetermined but clearly related to his unorthodox film style, his so-called “highbrow” interests, his purported inability to attract a large popular audience, and. in no small measure, his tendency to provoke resentment and schadenfreude in some quarters of the movie colony. Kane made the Hearst press his enemy, and Ambersons was disastrously recut by RKO because it was a more mature, leisurely, unsensational film than the Hollywood industry would allow. Even in its recut version, Ambersons remains one of the few movies to display the characteristics that Georg Lukács and Fredric Jatneson have associated with the most important forms of the classic historical novel: narratives that depict historically representative fictional characters whose lives are changed by large-scale social forces, and that tell of struggles between emerging and once-dominant forms of society without completely picking sides in the contest and thereby descending into costume melodrama. The supreme example of a film that fits the Lukács-Jameson model is arguably Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963). In its original form Ambersons might have been the equal of that picture, and in any event the loss of that version is tragic.

Welles’s problems were exacerbated by the death of Roosevelt and the postwar reemergence of the American right wing. Writing from the vantage point of California in the mid-1940s, cultural theorists Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno argued, “Orson Welles is forgiven all his offenses against the usages of the craft because as calculated rudeness, they confirm the validity of the system all the more zealously” (102). In fact, however, beginning with Citizen Kane and continuing until 1956, Welles was not only disliked by the Hollywood studios but also closely observed by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which compiled roughly two hundred pages of reports about him. For nearly ten years FBI operatives tracked his political activities, personal finances, and love life, following up tips from industry insiders, the American Legion, isolated crackpots, and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, who worked for the I Hearst press. In 1045, near the beginning of a Red Scare that would influence Hollywood tor the next decade, the FBI secretly designated Welles a Communist and a “threat to the internal security” of the nation. (A complete discussion of the FBI tiles, which I obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, may be found in Naremore, “The Trial,” 22-27.)

Although Welles had been one of the most celebrated directors of Popular Front theater and radio in the 1930s, the FBI took no interest in him until April 1941, one month before the U.S. premiere of Kane and at just the moment when William Randolph Hearst’s minions were mounting an attack on the film. At that juncture Hoover sent a memo to Assistant U.S. Attorney General Matthew McGuire listing Welles’s membership in over a dozen organizations “said to be communistic in character” and registering particular concern over his recent involvement with the Free Company, a group of writers and actors who were producing radio dramas on civil liberties for CBS. Welles’s contribution was a show called “His Honor, the Mayor,” which dealt with racial prejudice. Hoover noted that an American Legion post in California had described the show as “encouraging racialism” and that “spokesmen” tor the group had charged it and other shows in the series with being “subversive in nature and definitely communistic in aims although camouflaged by constant reference to democracy and free speech.”

As a result, Hoover ordered the FBI to compose a biographical sketch of Welles based on Who’s Who and journalistic sources. The resulting document noted his membership in Spanish relief committees, his support of Harry Bridges (the militant onetime Communist head of the International Longshoremen’s Union), and his stage production of The Cradle Will Rock. Agent F. E. Foxworth, author of the sketch, reported that, according to anonymous informant Welles has written stories which were apparently for the movies and … considered too far to the left.” Soon afterward the bureau compiled reports on two “subversive” productions by Welles: the Mercury Theater’s 1941 stage adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son, and Citizen Kane. The file on Native Son contained a copy of Wright’s novel and sixteen pages of clippings from newspapers such as the Daily Worker and the New Masses, all purporting to show “the communist teamwork invoked in the production of this play.” The much larger file on Citizen Kane contained thirty-two pages of clippings from left-wing journals, including an essay Welles had written three years earlier for the Daily Worker (“Theater and the People’s Front,” April 15, 1938). The report emphasized that William Randolph Hearst was often the victim of attacks by the Communist Party. “In fact,” its author said, breaking into a blustering tone worthy of Walter Parks Thatcher, “the evidence before us leads inevitably to the conclusion that the film ‘Citizen Kane’ is nothing more than an extension of the Communist Party’s campaign to smear one of its most effective and consistent opponents in the United States.”

Six months later, as Welles was preparing to leave for South America and begin shooting It’s All True, the FBI received a letter that set off a brief investigation, I quote parts of it below, with the errors in the original left intact:

Gentlemen:

Orson Wells whose activities and interests in Communistic circles and whose American sympathies are nil, one whose record you have in your files, has been cooking up some scheme having to do with Brazil in S. America. He is known to be pro-Russian. … He is associated in this scheme with [deleted] who lives in [deleted]. This man is a hothead, big word individual who is supposed to represent some newspaper [deleted] but hobnobs with alien Italians and is in reality a native of Portugal.. . .

These two plan to leave in a very few days for Brazil either by plane or ship.

They should be investigated at once and possibly prevented from going down there if you find cause for detention…. Its possible their intentions are legal but from reports, there is something screwy about this whole set up… . There is no time to waste on this tip.

From one who with others is engaged in quiet investigation of subversive actions. Take it or leave it, that’s up to you.

[Signature deleted]

The bureau decided to “take it,” but soon they discovered that their informant had used a fake name. When they made “undisclosed identity” phone calls to people mentioned in the letter and checked voter registration lists in Los Angeles, they learned that one of Welles’s sinister associates was a Republican. When they were subsequently notified that Welles had been given State Department permission to make a film in South America, they temporarily called off their agents. No additional information was filed until the next year, when agent D.M. Ladd reported to Hoover’s assistant Clyde Tolson that Welles was involved in the effort to defend seventeen Latino teenagers charged in the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial in Los Angeles. (In 1944, after numerous legal abuses and time in jail, these defendants were acquitted.) Later that year the FBI clandestinely searched the office of the Los Angeles County Communist Political Association but could find no record of Welles’s membership. Undeterred, the Los Angeles office of the FBI recommended that Welles be given a Security Index Card listing him as a native-born subversive and a communist.

Three weeks later Hedda Hopper alarmed the bureau by informing them that Welles was engaged in “special work” on behalf of FDR. Shortly afterward, on February 22, 1945, Hoover sent an order for Welles to be placed on the FBI Security Index, which contained “only the names of those individuals who can be considered to be a threat to the internal security of this country.” Regular reports on such individuals were required. Hoover added. Agent R.B. Hood, who was in charge of the Los Angeles office, began submitting the reports to Hoover, passing on more news from Hedda Hopper, such as the rumor that Welles would be going to Russia to film Crime and Punishment, and gathering the sort of information one might use for blackmail. According to Hood, Welles was spending “considerable evenings with [name deleted], former Main Street burlesque strip tease artist, who has recently promoted herself to a higher type of nightclub appearance…. Also some time ago, when WELLES appeared in San Diego in connection with a bond tour[,] he took some girl, other than his wife.” His finances were being mishandled by an unnamed associate. Hood reported, “leaving him practically broke,” and his marriage to Rita Hayworth appeared to be ending. To top things off, he was also having an affair with “a movie actress [name deleted] who has recently been receiving considerable publicity.” At the conclusion of one of the reports, Hood appended a list of persons in Hollywood—their names deleted from the official document—who would be “glad to be of any possible assistance.” “Proper coverage of the telephone conversations between WELLES and [name deleted] may reveal information of interest,” he added.

The timing of these actions was significant. The war was coming to an end and a purge of American leftists was in the offing; Welles had campaigned vigorously for FDR’s fourth term and for Henry Wallace; and over the next few years he would become involved in the newly formed United Nations and Louis Dolivet’s Free World Association, meanwhile writing a syndicated political column for the New York Post and flirting with the idea of running for office. By 1948, however, his Hollywood career was virtually at an end: The Lady from Shanghai, which he was able to make only because of his marriage to Hayworth, was loathed by Columbia Pictures and mangled in the studio’s reediting; and the extremely low-budget Macbeth was recut by Republic Pictures (in the process removing one of the first ten-minute takes in the history of movies) and its soundtrack completely redubbed. By the early 1950s, as the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and the McCarthy era dawned, and at about the time when Jules Dassin and Joseph Losey became expatriate directors, Welles was in Europe and North Africa making Othello. An anonymous informant sent the FBI a photo of Welles dining with Palmiro Togliatti, the legendary head of the Italian Communist Party, along with a message in French saying that the photo ought to be brought to the attention of the State Department with the aim of having Welles “brought before a court in charge of prosecuting actors suspected of Un-American activities and perhaps even excluded from Hollywood definitely.” But the investigating agent concluded that Welles was being “bled white” financially by communist sympathizers, had never actually been a member of the party, and was no longer any particular threat.

Welles did not return to America for any significant length of time for almost a decade. Most of his theatrical and cinematic activity in those years—during which he starred in The Third Man (1949), wrote several film scripts, and directed Othello (1952) and Mr. Arkadin (1955)—took place in Italy, North Africa, France, Germany, England, and Spain. This was also the period in which he began acting in bad pictures in order to raise money for the movies he wanted to direct. In 1953 he was briefly in New York to act in Peter Brooks’s TV version of King Lear, and in the late 1950s is he returned to the United States for a longer period, performing a magic act in Las Vegas, making numerous guest appearances on TV, and filming a brilliant TV pilot (“The Fountain of Youth” I for the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz production company. In 1958, slightly more than a decade after Macbeth, he was given the opportunity to write, direct, and act in the Universal Pictures production of Touch of Evil. The resulting film was recut by the studio before its release and had no financial importance for its producers. Welles began filming Don Quixote in Mexico and then returned to England, Spain. France, and various other European locations for another decade, the period of The Trial (1962), Chimes at Midnight (196s), and The Immortal Story (1968). From approximately 1968 until his death in 1985 he divided his time between Hollywood and Europe, making frequent guest appearances on the Dean Martin television show and filming F for Fake (1974) and a number of incomplete pictures, including The Deep and The Other Side of the Wind.

Several of Welles’s European producers gave him at least as many problems as the old Hollywood studios had done. Information on the costs and box office receipts of his post-Hollywood films is almost irrelevant because those films are so far afield of the budgets and marketing strategies that dominated the industry after midcentury. Late in his career he encountered major tax problems in the United States because of money he had earned in Europe, and he began to take on increasingly dubious backers, including, against all his progressive instincts, the Shah’s government in Iran. He was revered by the French New Wave and frequently honored by American cinephiles, but in the nearly forty years after he filmed Macbeth (1948) he only once exercised his talents in a Hollywood film His later work is less political and satiric than his work in Hollywood. The major part of his career was spent as a pioneering independent director/producer, an artist who created films almost as an avocation. Still a kind of celebrity from the 1950s until his death, his career made hash of highbrow, middlebrow, lowbrow distinctions. Michael Anderegg puts it nicely: most of Welles’s post-Citizen Kane work in the movies was an attempt to “drive his gypsy wagon outside the great hall of the culture industry” (Orson Welles, 57).

Stanley Kubrick’s first professional opportunity came just as Welles’s American career was winding down. In 1945, at the age of seventeen, he sold Look magazine a photograph of a New York newspaper vendor grieving over the death of Franklin Roosevelt. This image enabled Kubrick to became a member of Look‘s photographic staff, a job that sent him traveling around the United States and Europe and resulted in the publication of more than nine hundred of his pictures. Between 1945 and 1950 he was directly involved with the New York School of photographers, which included Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus. Like Kubrick, many in this group were from Jewish immigrant families, and their livelihood was made possible In the burgeoning market for photojournalism in the slick picture magazines and the tabloid newspapers. Its senior members had lectured at the New York Photo League, a Popular Front organization that nurtured the careers of Weegee, Berenice Abbott, Morris Engel, and Lisette Model. Kubrick’s early self-produced films, especially Killer’s Kiss (1955), which was shot on the streets of New York, show a strong indebtedness to this cultural milieu; but his later films, made in the period of the Cuban missile crisis, the assassination of JFK, and the Vietnam War, convey a bewildering mixture of political attitudes.

Although most of Kubrick’s career was spent abroad, he remained a star director, manufacturing dream images of space travel, the Vietnam War, and contemporary Manhattan all from within a few miles of his English residence. By the mid-1960s he had acquired the aura of an intellectual Mr. Cool who adopted silence, exile, and cunning as a way of dealing with his career. But while he was often portrayed as a maverick and an exile, the truth is more complicated. In the best account yet written of Kubrick’s business relationship with Hollywood (from which I have taken economic statistics), Robert Sklar has pointed out that Kubrick never left the big studios behind:

Stanley Kubrick’s career as a filmmaker is deeply interconnected with the American motion picture industry, fie has worked at one time or another with nearly all the so-called “majors”: United Artists, Universal, Columbia, MGM, and Warner Bros. These companies have distributed his films and have participated in financing some of them. These connections have enmeshed Kubrick and his films in the structures of the American film business; despite his geographical self-exile from Hollywood, Kubrick continues to be regarded as an American filmmaker, while other expatriate directors, like Richard Lester and Joseph Losey, worked more closely with British and continental production and distribution companies and came to be seen as members of the Anglo-European film community. (“Stanley Kubrick and the American Film Industry,” 114)

Sklar appropriately calls Kubrick a “self-exile,” as opposed to a figure like Joseph Losey, who was driven out of the United States for political reasons. It also seems to me that Kubrick isn’t the same sort of American abroad as Orson Welles. Jonathan Rosenbaum has pointed out that Kubrick and Welles “ended up making all the films they completed after the 1950s in exile, which surely says something about the creative possibilities of American commercial filmmaking over the past four decades” (Essential Cinema, 267-68). The basic point here is valid and important, but it’s also important to note that Welles was persona non grata in Hollywood during the late 1940s and became a peripatetic citizen of the world, whereas Kubrick established a settled existence, remaining close to American production facilities but far enough away from Hollywood to protect his art. In Sklar’s words, Kubrick “hardly ever hesitated from playing the American film business game,” much of the time “by his own rules” (114).

There was always a tension between Kubrick’s artistic aims and Hollywood’s conventional way of manufacturing entertainment; he disliked life in Los Angeles, but he rarely had to yield authority over his films. His ability to maintain control was due in part to his talents as a producer-businessman, and partly to the tact that when he took the first steps in his career the industry was undergoing major changes. A 1948 Supreme Court ruling had divested the major Hollywood studios of their theater chains and the popular audience was increasingly obsessed with television. Movie house attendance in the United States had declined by some forty million, but two developments in the world of exhibition created markets for independent producers: the drive-in, or “passion pit,” which favored exploitation films, and the urban or college-town art theater, which specialized in foreign pictures. In the trade, the art theaters came to be known as “sure-seaters” because their audiences were loyal and their dims tended to attract strong reviews from critics. The films were sometimes labeled “mature,” presumably because they were enjoyed by sophisticated and discriminating viewers, but also because they were more openly sexual than Hollywood’s products and could be promoted in terms of a softly pornographic sensationalism. At first few it any American filmmakers seemed aware of these new circumstances. During the early 1050s, the only American-born director who made inexpensive English-language films that found a natural home in art houses was Orson Welles; but Welles’s Othello and Mr. Arkadin were European imports, without the distribution networks that would later develop for independent and off-Hollywood films.

Kubrick can claim the distinction of being the first true American independent of the art-house era. He used $53,500 of his and his relatives’ money to produce, direct, photograph, and edit an extremely arty war film entitled The Shape of Fear, which attracted the interest of a legendary distributor of foreign pictures, Joseph Burstyn, the man who had brought Open City, The Bicycle Thief, and Renoir’s A Day in the Country to America. “He’s a genius!” the excitable Burstyn purportedly said after meeting the twenty-four-year-old Kubrick. Burstyn immediately declared The Shape of Fear an “American art film,” changed the title to the more provocative Fear and Desire, and in March 1951 booked it into New York City’s Guild Theater, an art house located in Rockefeller Center. It received a “B” rating from the Legion of Decency because of a sex scene involving a woman strapped to a tree, but it also enjoyed a degree of mostly favorable critical attention.

Kubrick’s next film, Killer’s Kiss, sell-produced for $75,000, was distributed by United Artists and shown mainly in fleapits. His Hollywood career began shortly afterward when he met James Harris, a wealthy contemporary who shared his artistic ambitions. Their first project, distributed and partly financed by United Artists, was The Killing (1956). UA disliked the film’s splintered narrative structure and gave it almost no promotion or chance to earn profits; nevertheless, it attracted the attention of Hollywood cognoscenti at a moment when the movie business was being driven by producers and stars who controlled their own production units. Kirk Douglas, who was at the height of his fame during the period, was much impressed with The Killing, and when he saw a script for Kubrick’s newest project, Paths of Glory (1957), he offered to take the leading role and to pressure United Artists into financing and distributing the film. The price he exacted was considerable: Harris and Kubrick had to agree to move their operation to Douglas’s Bryna Productions and make five other pictures with Bryna, two of which would star Douglas. Harris and Kubrick reluctantly agreed, and Paths of Glory went before cameras in Munich, Germany, budgeted at approximately one million dollars, a third of which went to the star. Harris and Kubrick waived their fees and agreed to work for a percentage of the picture’s profits.

The working relationship between Douglas and Kubrick was tense, and Douglas had more influence over the script of Paths of Glory than most critics have recognized. The film nevertheless gave Kubrick a good deal of cultural capital and the reputation of having collaborated with a major star. Moreover, his new contract led to his being hired to direct Spartacus (1960), produced by Bryna and Universal Pictures, which was budgeted at twelve million dollars. At the time, this was the most expensive movie ever shot chiefly inside the United States. MGM’s remake of Ben-Hur in the previous year had been slightly more expensive, but it was produced at Cinecitta in Italy, where Hollywood companies obtained tax advantages and cheaper labor. During the 1960s the so-called “flight” from domestic production, coupled with the turn toward expensive spectacles, had become so commonplace that when Spartacus opened, the recently elected John F. Kennedy made a special point of attending a showing at a regular theater in Washington, D.C”., thereby calling attention to Douglas’s and Universal’s attempt to keep U.S. money at home.

Spartacus represents the only alienated labor of Kubrick’s film career and has very few moments in which one can sense his directorial personality. Anthony Mann was in charge of the opening sequences, which are as good as any of the others. Kubrick’s hand seems most evident in the sexually kinky moments—the visit of Roman aristocrats and their wives to the gladiator school, and the not-so-veiled homosexual conversations between Crassus and his slave, Antoninus. He had no voice in the casting or the development of the screenplay, nor did he supervise the editing. He disliked the script, which he described to Michel Ciment a “dumb” and ” rarely faithful to what is known about Spartacus” (151). (Kirk Douglas has said that in spite of such complaints Kubrick offered to take credit for the work of blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo; Douglas credited Trumbo and defied the blacklist.) To make matters worse, Kubrick had trouble with veteran director of photography Russell Metty, a skilled practitioner of crane shots who had photographed Welles’s Touch of Evil. As a result of Metty’s intransigence, very few scenes in Spartacus employ the source illumination we identity with Kubrick. As Kubrick told Ciment, “If I ever needed any convincing of the limits of persuasion a director can have on a film where someone else is the producer and [the director] is merely the highest-paid member of the crew. Spartacus provided proof to last a lifetime” (151). Spartacus gave Kubrick a big payday (Douglas never profited from the him), but he asked to be released from his contract with Douglas, and Douglas consented. There was bad blood between the two, but insofar as Hollywood was concerned, the most impressive thing on Kubrick’s resume was Spartacus, which showed that he could manage a supercolossal picture with big stars.

Another opportunity arose when Kubrick and Harris acquired the rights to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita just prior to its publication. After extensive battles with censors, they made the film in England, where, under the recently enacted Eady Plan, they could enjoy substantial tax advantages it at least 80 percent of the people they employed were British citizens. This arrangement provided Kubrick with distance from Hollywood’s usual ways of doing business while giving him considerable technical resources. The film, with a final budget of approximately two million dollars, was made without a distributor but was ultimately released by MGM in 1962. The least critically successful but the most profitable of the Harris-Kubrick pictures, it earned almost twice its cost in the United States alone.

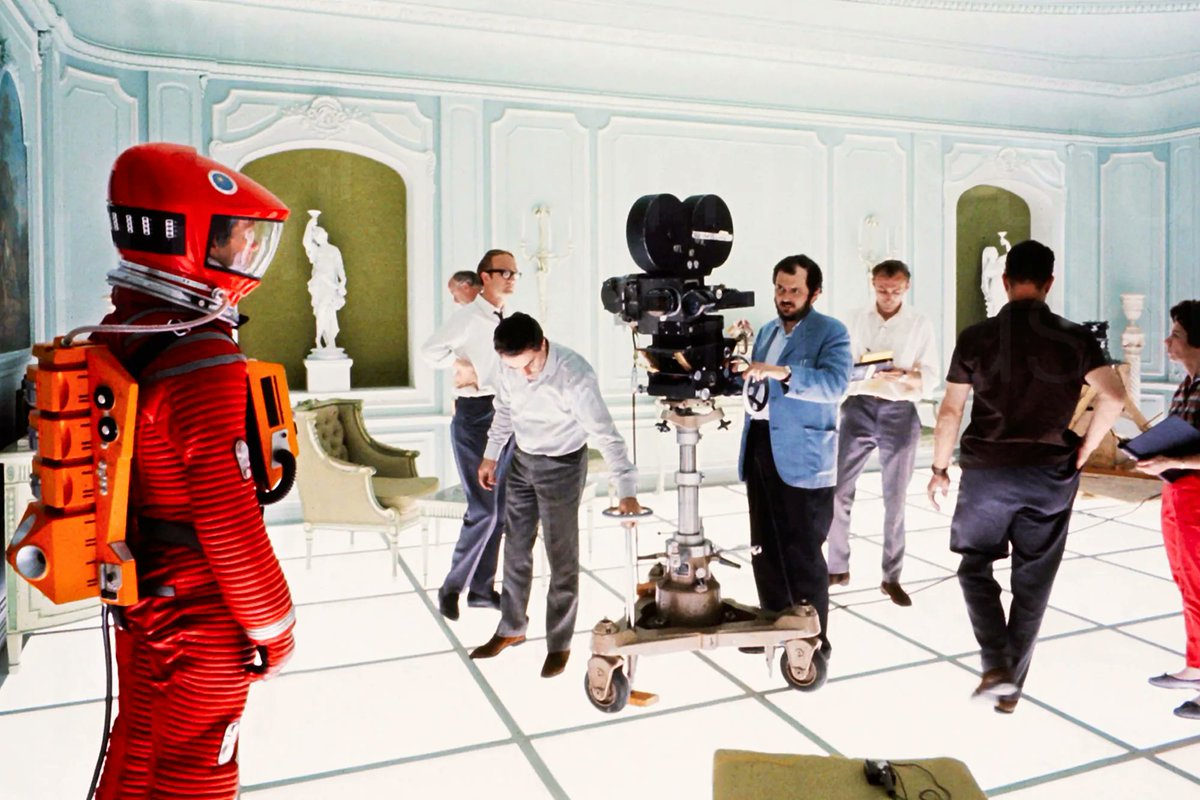

After Lolita, Harris and Kubrick amicably dissolved their partnership and Kubrick’s career entered a new phase in which he became his own producer and shot all of his films in England. His first two pictures under this arrangement, Dr. Strangelove and 2001, were major box-office hits, tapping into a youth audience that would serve him well over the next decade. In 1968, 2001 was filmed for approximately 10.5 million dollars, and by 1973 it had earned approximately 28 million dollars in domestic and foreign rentals, although Kubrick received little of that money because MGM was still charging him for distribution fees and interest on the financing of the film. He was unable to acquire financing for his next project, an epic film about Napoleon for which he had done massive preparation, but his disappointment must have been ameliorated when Warner Brothers offered him a contract even better than the one Welles originally signed with RKO. In 1970, John Calley, the executive vice-president for production at Warner, signed Kubrick tor a three-picture deal in which he would have a unique relationship with the studio. He could remain in England, where Warner’s London office would fund the purchase, development, and production of properties tor him to direct; he was guaranteed final cut of his films; and his company, Hawk films, would receive 40 percent of the film’s profits. At about the same time, Calley offered Welles a chance to make a picture at Warner, but Welles declined, in part because he was leery of big studios.

The first picture Kubrick made under the new arrangement, A Clockwork Orange (1971), was budgeted at two million dollars and by 1982 had earned forty million dollars, making it the most profitable production of the director’s career and one of the studio’s biggest hits of the decade. The profits, moreover, were achieved despite the fact that A Clockwork Orange was an exceptionally controversial picture with a limited distribution. British newspapers accused it of prompting a series of copycat killings, and Kubrick began to receive death threats. In response he withdrew A Clockwork Orange from exhibition in England for his entire lifetime—a step that no other director, then or now, has had the power to take. In the United States, Kubrick personally supervised the film’s promotion campaign, targeting every student newspaper and alternative radio station in America. His success was such that Ted Ashley, the chief executive at Warner, announced that Kubrick was a genius who combined “aesthetics” with “fiscal responsibility” (Sklar, “Stanley Kubrick and the American Film Industry,” 121).

Kubrick remained at Warner for the rest of his career, forming a personal bond with the CEO Steve Ross (also a friend of Steven Spielberg). His ascendancy in the early 1970s had something to do with the “New Hollywood,” a phenomenon he slightly predates, which is determined by the relative independence of U.S. exhibition, the liberalization of classic-era censorship codes, and the rise of youth culture. But by the late 1970s Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were producing Hollywood blockbusters in the same British facilities Kubrick had used, and Kubrick’s ability to attract sufficiently large audiences was ending. After A Clockwork Orange he made Barry Lyndon (1975), which employs many of the same themes and techniques that were planned for his aborted Napoleon project. The film, which is slightly over three hours long, cost eleven million dollars to make and barely placed in the top twenty-five grosses of the year; it eventually earned a profit, but Variety called it a flop.

Writers in the trade press accused Kubrick of arrogance, in part because he had kept the production of Barry Lyndon largely a secret. His bigger problem, however, was that the top money-maker of the year was Jaws, which earned 113 million dollars, almost doubling the earnings record of any previous film. From this experience the studios learned new marketing practices: saturation booking of tent-pole films across the entire country, massive TV advertising and huge promotional campaigns, prerelease payments from exhibitors, and guaranteed playing time in theaters. Soon the movie studios would once again be vertically (and horizontally) integrated, and the “New Hollywood” would become a memory.

Kubrick’s initial response was a highly commercial project, The Shining (1980). (He had declined Warner’s offer to direct The Exorcist, which went on to become one of the studio’s most profitable investments.) The Shining was budgeted at 18 million dollars and earned nearly 40 million in domestic rentals—a substantial sum, but not terribly impressive in a year when Lucas’s The Empire Strikes Back brought in 140 million. The gap between “aesthetics” and “fiscal responsibility” was growing wider, and Kubrick’s inability to appeal to audiences beyond the urban centers was becoming more noticeable. Warner remained faithful to him and appreciated the fact that his late films, despite their slow production schedules, were shot with relatively small, efficient crews. Even so, the periods of silence between his films grew longer, and he made only two more pictures before his death.

As all this indicates, Welles and Kubrick left their native country for very different reasons. We might ask if they lost anything in the process. Welles, though a Midwesterner, had begun his theatrical career in Ireland and was always something of an internationalist. One of his major artistic preoccupations was the death of an old world in the face of “progress”—a theme adumbrated in Kane, developed in Ambersons, and repeated in his European films, especially in Arkadin, Chimes at Midnight, and Don Quixote, all three of which juxtapose medieval Spanish settings against the encroachments of modernity. In this sense, his move to Europe was consistent with his career as a whole. Most of his films on the continent were financed in crazy-quilt fashion, and yet he managed to produce two distinguished adaptations of Shakespeare, two films in modern settings that provided models for younger directors, an intriguing television drama that played theatrically, and an essay film that was far ahead of its time. He often said that what he missed most about Hollywood was its technical expertise. In Europe he had to modify his style to suit the fragmented, catch-as-catch-can nature of his productions, and in his last years he had to depend upon a kind of bricolage and the garish photography of his loyal American admirer, Gary Graver. Even so, much of his European work is tilled with dazzling cinematic effects achieved with great ingenuity What is missing, in my own view, is contact with American mores, myths, and politics. The European films, with the exception of Arkadin, lose touch with the topicality and leftist satire of the American work and tend to retreat into the world of literary adaptation. The Third Man, which Welles did not direct, was obviously about contemporary Europe, but The Trial, partly because of budget constraints, was about an abstract Europe. Touch of Evil is a better film than either of these, in part because it puts Welles back in an American milieu during the civil rights era and takes full advantage of his talents as a satirist and moralist.

Welles began with a Hollywood studio at his disposal and ended as an independent Filmmaker who did nearly everything—on The Trial, for example, he was not only writer, actor, and director but also second unit photographer, editor, and sound designer. Kubrick, on the other hand, began as an independent filmmaker who did nearly everything and rose to command stars and big studio resources in England. Despite the fact that he never lost his Bronx accent, Kubrick had something of a European sensibility, Jonathan Rosenbaum and loin Gunning have each pointed out to me in conversation that he can be viewed as not simply a Hollywood modernist and futurist but also the last of its Viennese auteurs. His ancestors were from Austria-Hungary and his intellect was shaped by the protomodernist, largely Jewish culture that originated in pre-World War I Vienna. In addition to Freud, he was interested in Stetan Zweig and Arthur Schnitzler. and he often stated his admiration for Max Ophüls, who was born in Saarbriicken but is often regarded as the quintessential Viennese director. The Viennese cultural nexus may not seem evident in a film like 2001, but that film is at least distantly related to Lang’s Metropolis, and the famous image of a shuttle docking at a revolving space station to the music of “The Blue Danube” not only makes a sly Freudian joke but also evokes memories ot Ophüls’s Lola Montes ( nji;|.

lor the most part. Kubrick used Britain for non-British subject matter. (Michael Herr, who collaborated with Kubrick on Full Metal Jacket | 19S7I, wrote, “I’m not sure he even really knew he wasn’t living in America all along” |4o|.) David Thomson has severely criticized Kubrick’s Lolita, remarking that Nabokov’s “love story to America was ruinously shot in England” (Biographical Dictionary, 408). It seems to me, however, that Nabokov’s America is mediated by the voice of a European exile (in his own commentary on the novel, Nabokov describes his version of America as a theatrical “set” and a “fantastic and personal” world), and that in roughly analogous fashion, the British workers on Lolita create an intangible air of America seen lucidly through a slightly foreign lens. It might also be noted that while Kubrick’s next two films involved American characters. Dr. Strangelove ends with the quintessential British pop tune of World War II. and the astronauts in 2001 watch television broadcasts from the BBC. The only Kubrick film that deals more or less directly with contemporary Britain is A Clockwork Orange, which is also his most repellant film, depicting modern society as based on nothing more than innate predatory violence and rationalized, utilitarian coercion. Kubrick jettisoned the Catholic religious message of Anthony Burgess’s novel and made a film whose politics are difficult to define. A Clockwork Orange shares Adorno’s late-romantic devotion to Beethoven, his relentlessly satiric attitude toward socialism and fascism, his disdain for bureaucrats, his derisive response to kitsch, and his despair over Enlightenment rationality. Kubrick’s savage treatment of reitication and alienation under modernity isn’t far from what one finds in the “Culture Industry” chapter of Dialectic of Enlightenment. and his treatment of sex roughly corresponds to that book’s chapter on the Marquis de Sade (“Enlightenment as Morality”), which argues that Sade’s libertinism was merely a logical development of the liberal bourgeois subject—a disavowal of religious superstition, a “busy pursuit of pleasure,” and an extension of reason, efficiency, and social organization into the realm of the senses (69-70).

Kubrick’s other film about Great Britain is Barry Lyndon, based on Thackeray’s The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1856), which tells the story of an eighteenth-century Irish rake who seduces his way into the British aristocracy. Kubrick’s approach to the subject is exactly the opposite of Thackeray’s; in place of a rollicking satire he gives us a somber tragedy of manners that ends on the eve of the French Revolution. As a Jewish-American who eventually settled into a British country house, he seems to have identified with a social outsider like Barry, whom he depicts as an unwitting and unsuccessful rebel against his times. For roughly similar reasons Kubrick had identified with the Corsican upstart Napoleon, who gained ascendancy over France’s old regime and became one of the founders of the modern world. I suspect that Kubrick’s reference to 1789 at the end of Barry Lyndon functions less as an optimistic tribute to democracy than as a portent of the Napoleonic era and a nod to a film he never made. Barry Lyndon nevertheless resembles the epic, unmelodramatic model that Lukács and Jameson have championed in their readings of the classic historical novel. Kubrick had intended to portray Napoleon as a tragic superman, both a dictator and a force of Enlightenment liberalism, worthy of being placed in relation to the killer ape and the star-child in 2001. He was unable to realize that ambition, but it became a kind of structuring absence in the fictional, “middling” characterizations of Barry Lyndon and one of the chief reasons why that film has such beauty, strangeness, and emotional force.

At the end of then careers Welles and Kubrick were honored in America, and the separate occasions were symptomatic of their forms of exile. Welles received the American Film Institute’s third Life Achievement Award in 1975 and turned the televised ceremony into an overt appeal for “end money” to complete his latest movie. He showed two clips from The Other Side of the Wind: the first was a satiric depiction of a Hollywood celebration in honor of a famous film director, the second a scene in which one of the director’s henchmen unsuccessfully tries to obtain financing from a big studio boss modeled on Robert Evans. Welles followed these excerpts with a speech in which he described himself as a lifelong “contrarian” and a “neighborhood grocery in the age of supermarkets.”

Stanley Kubrick’s acceptance of an honor was in every way different but no less filled with ironies. In 1999, while editing Eyes Wide Shut, he was presented with the D.W. Griffith Award from the Director’s Guild of America. He didn’t travel to Los Angeles to accept the award. Appearing as a ghostly image on closed-circuit TV, he used his acceptance speech to confirm his faith in the bit; artistic ambition of Griffith. Griffith’s career, he recalled, had often been compared to the Icarus myth, “but at the same time I’ve never been certain whether the moral of the Icarus story should only be, as is generally accepted, ‘Don’t try to fly too high,’ or whether it might also be thought of as ‘Forget the wax and feathers and do a better job on the wings.'” It might be argued that Kubrick had done a better job on the wings, but, unlike Welles, he had never flown far away from the labyrinth.

James Naremore – Invention – Without a Future – Essays on cinema, University of California Press, 2014, pp. 198-214

1 thought on “WELLES AND KUBRICK: TWO FORMS OF EXILE”

JUST FINISHED VIEWING ME AND ORSON WELLES FILM. THANK YOU FOR SUCH AN IN-DEPTH LOOK AT THE WORKS AND CINEMATIC ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF WELLS AND KUBRICK. AS A LOVER OF MOVIES USED MOVIES THEM TO TEACH ENGLISH AND AMERICAN LITERATURE AT THE UNIVERSITY AND HIGH SCHOOL LEVEL IN PUERTO RICO.