Review – THE DEER HUNTER

Gordon Gow sees Michael Cimino’s impressive essay on the traumatic effect of the Vietnam war upon Americans…

from Films and Filming, March 1979, pp.30-31

It is hard to believe that The Deer Hunter is only the second film that Michael Cimino has directed. He navigates its tricky course with the confidence of an accomplished veteran. His one previous work as director, the diverting Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974), and his experience as screenplay writer on that, as well as on such creditable things as Silent Running (1972) and Magnum Force (1973), gave no hint that he would graduate at what seems like a giant bound to a substantial and lengthy essay on the traumatic effect the Vietnam war has had upon Americans.

His representative figures are three men who work in a Pennsylvania steel mill, and whose lives are enclosed and regulated by the traditional patterns of the mill town. In the first of three sections into which the film is divided, the home life atmosphere as it was in 1968 is carefully established in order to derive the utmost contrast from the second phase of the story in Vietnam. The long beginning, in fact, is quite dangerously protracted, but once the three men are hurled into the brutish climate of war, and of torture at the hands of the Viet-Cong, attention is gripped and remains so throughout the final passages of the return home, where the men in their tragically altered conditions are unable to resume their former lifestyles. The controlled emotional quality of this is reinforced in narrative terms by a return to Saigon in quest of a missing member of the trio whose memory has failed, and who has succumbed to an eerily decadent way of life, so astutely depicted as to steer well clear of mere sensationalism while nevertheless tightening the screws of nervous tension.

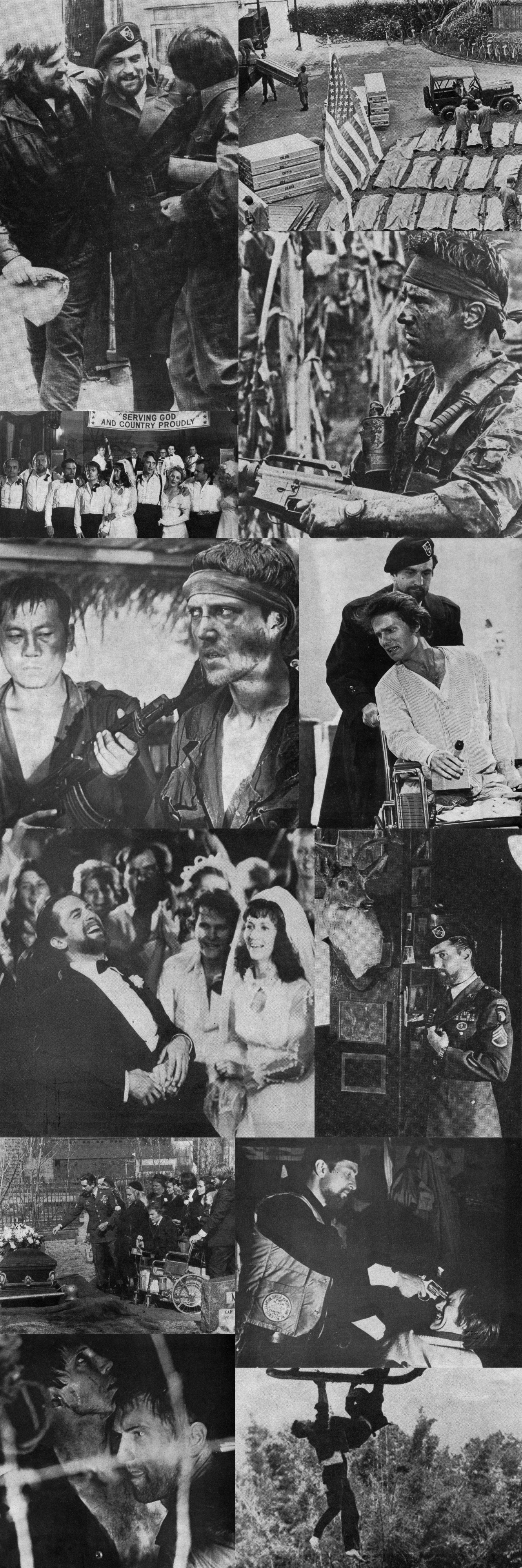

Like the storyline, the three leading characters take some time to engage wholehearted interest. At first they come across as mainly slobbish, guzzling beer and lacing their rather dull conversations with those excremental and copulatory expletives which five or six years ago were lending a raw vigour and even a certain shock value to movie dialogue, but which time and custom have rendered tedious. However, these characters grow on one, not least on account of the skill with which their transformations are portrayed by Robert De Niro (Michael), Christopher Walken (Nick) and John Savage (Steven). All are provided with what could easily be construed as opportunities to ham, but no such liberties are taken, to the credit of the actors and of Cimino as well. De Niro is especially subtle as Michael, a private man for all his show of prankish high spirits, and one who relishes quietly his capabilities as a leader and can apply them with asperity if he chooses, but whose inner strength is impressively demonstrated when he pacifies the understandably hysterical Steven and Nick as they face up to the Viet-Cong torture-game of Russian roulette. In the absorbing final section, although Walken and Savage have a dramatic advantage in showing physical signs of their wartime afflictions, De Niro’s unstressed impression of deep-seated bitterness, mingled with continuing strength of will, brings a valuable realism to scenes that skirt the hazards of sentimentality.

While De Niro, Walken and Savage carry the bulk of the acting responsibility, the entire cast is well chosen, and Meryl Streep especially is to be singled out for bringing to the fairly routine character of a ‘girl left behind’ an utterly persuasive depth and a genuine poignancy.

Vital though the performances are, however, I find myself equally if not more impressed by the visual style, the sheer filmic essence of The Deer Hunter, which denotes an ideal meeting of minds between Cimino and his cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Deliverance, Sugarland Express, etc). Constantly one responds to the image, from the early shots of golden flames and molten steel in the blast furnaces, and the ornate stillness of a Russian Orthodox Cathedral, the setting for Steven’s marriage which dominates the first section of the film. It is visual power as much as anything that sustains the overlong sequence of the wedding celebration, a welter of ethnic quaintness and laborious inebriation, enhanced by potent compositions and one telling if elementary piece of symbolism when bride and groom are given an intricate vessel of wine and told that if they can drink from it without spilling a drop they will have good luck forever, whereupon a couple of splashes of red soil the whiteness of the bridal gown.

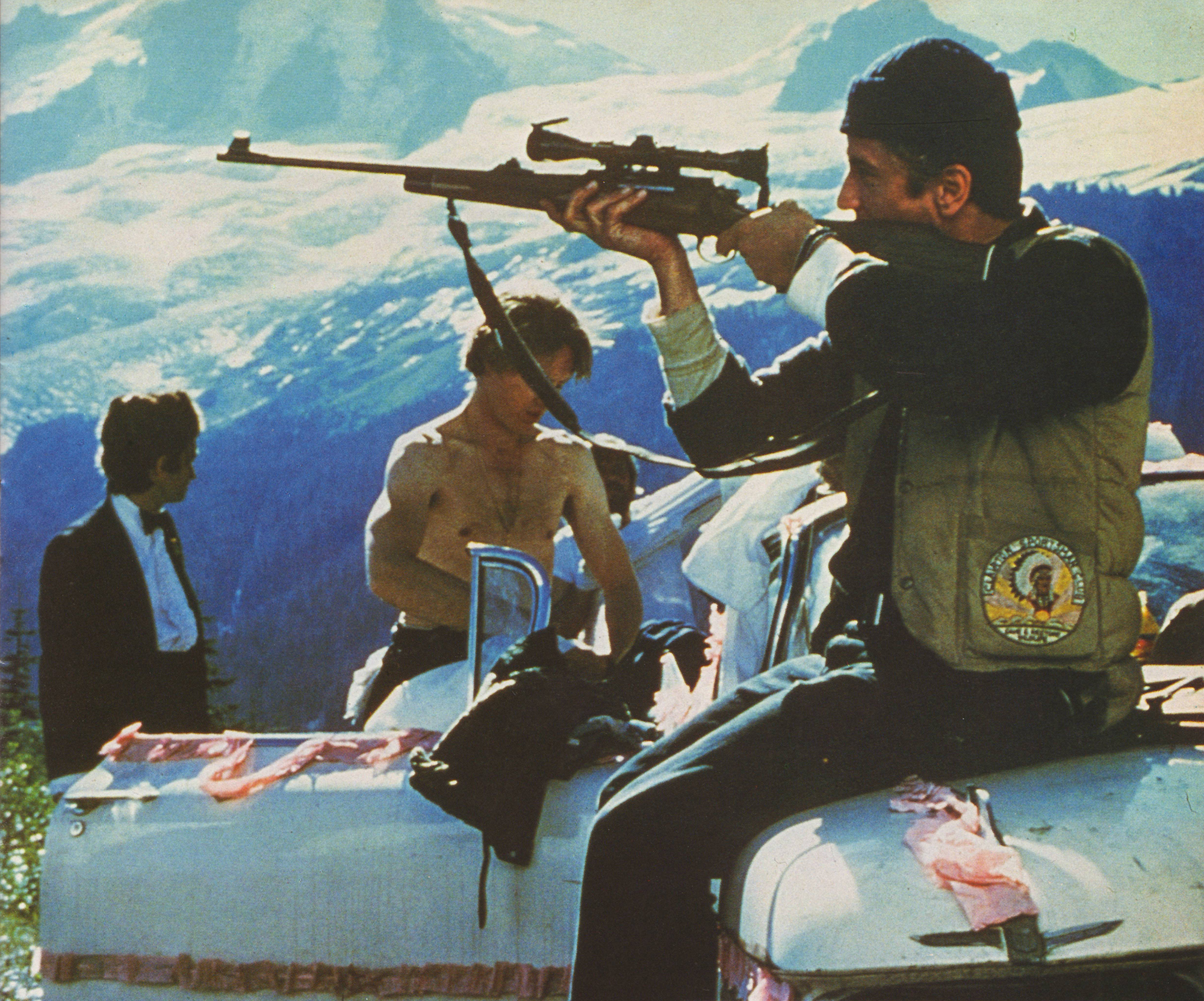

The first deer hunting sequence, in which Michael’s prowess gives the film its title, has the very feel of cold mountain air in its wonderfully clear pictorial quality (Mount Baker in the state of Washington serving for the Alleghenys), the hills standing out sharply until capped by the purest of mists, and the effect only slightly diminished by a corny overlay of music in the ‘heavenly choir’ tradition. Here the graceful deer is seen to die an ugly death in equivocal token of man’s virile sport that will soon be escalated into something more emphatically culpable.

Although the ground is well prepared for the move to Vietnam, the contrast when it comes is sudden and startling. After the hunt we see the men in their regular Pennsylvania bar where a piano is quietly played, and upon their reverie the soundtrack imposes the loud throb of a helicopter, which belongs to the next shot, the start of the second section of the story, in the untidy terror of war (Vietnam being represented by locations in Bangkok). The prison camp sequence and the dehumanising torture certainly look as if they have been aimed at the gut of the movie spectator who has supp’d full with horrors, and they should surely reach their target. This, of course, is very much to the film’s point.

Strong as the mid-section is, the final passages of The Deer Hunter carry as great a punch in their delineations of war’s grim inroads upon the human spirit. At the same time the images often relieve the mood with small tokens of consolation: in a kitchen just off the familiar bar, the right hand corner of the frame is occupied by a neat still life of cabbage, celery, eggs and tomato; in the mountains, Michael climbs a rocky hillock, and for a second or two is reflected in a wide still pool below. His attempt to resume hunting proves impossible. He fires over the deer’s head. And by this time the metaphor seems not the least bit trite. It holds, as securely as the tension when Michael goes back to Saigon and discovers the debilitated Nick, who is being exploited in a gambling den which specialises in the Russian roulette that the Viet-Cong applied as torture. Here we have the ultimate denigration of manhood, courage equated with absurdity.

There can be no pat conclusion to such a heart-felt narrative. Instead, Cimino provides a wry one: a gathering back in Pennsylvania, after a funeral, and a spontaneous, mindless singing of ‘God Bless America’, bringing softly and sourly to a close a film whose demerits can readily be forgiven, so firm is its core, so rewarding its use of the medium.

Gordon Gow